The winter of 1777-1778 was a cold and bitter one for the battle-weary Continental Army at Valley Forge, as it contended with shortages of food, clothing and medical supplies and suffered from starvation, exposure and sickness. George Washington, the commander-in-chief, elected to winter over with his 12,000 troops, plus 400 women and children. During that time, he suffered deeply under the crushing weight of responsibility, not only for them, but also for the cause of the American Revolution.

Valley Forge was a military encampment more than two miles long, consisting of crude log huts, each one crowded with soldiers. During the course of six months (from December to June), Washington would watch as diseases such as influenza and typhoid claimed around 2,000 members of his force. In contrast, the British army, ensconced approximately 20 miles away in Philadelphia under Gen. William Howe, enjoyed much better conditions in warm colonial homes.

However trying those days were for Washington and his troops, during the ensuing months, positive developments eventually began to emerge, so the army that paraded forth in June 1778 was a better trained and equipped force than the one that had marched in during December the previous year. A number of factors would come into play during the course of the winter to promote that fact. Baron Friedrich von Steuben, a Prussian military officer, provided important tactical training for the American troops, enabling them to successfully fight the British using European military tactics of battle and operate as a professional, unified army.

Washington was able to successfully thwart a subversive attempt by some of his officers to demote him from the commander-in-chief role, thereby bolstering his position and authority. He was also able to work with and convince the Continental Congress to procure much-needed supplies for his men. Another big boost came when France and the United States subsequently signed a treaty on Feb. 6, 1778, creating a military alliance between the two countries. That was a major and positive turning point in the revolutionary cause.

During the spring of 1778, probably sometime in early April, one event, seemingly insignificant compared to the whole backdrop of the Valley Forge experience, occurred in the life of George Washington that doubtlessly bolstered his spirits. A young American officer, Capt. Henry Fauntleroy, appeared at Washington’s headquarters near Valley Forge Creek, carrying a nicely finished walnut display case and bearing a letter from his brother-in-law, Thomas Turner. The letter, quoted as it was written, and dated March 22, 1778, reads:

Altho [Although] I have not the honor of being personally acquainted with your Excellency, nevertheless I am far from being a stranger to your distinguished merit, both in private and publick [public] life; your indefatigable zeal and unwearied attention to the true interest of your native country, since the commencement of these differences, must excite the warmest sense of gratitude in the breasts of every American that is not callous to the rights of humanity; That it may please the supreme Disposer of human events to crown you with success in this important struggle and speedily put an end to the distressing scenes of this unnatural war, is the fervent wish of your,

Excellency’s respectful + obedient h’ble [humble] servant.

Thomas Turner

March 1778

P.S. I have transmitted to your Excellency a pair of pistols & to your acceptance of which will confer a singular obligation on T.T.

Washington opened the display box, and, to his delight, found an exquisite pair of matched English pistols. Picking them up and admiring them, he then thanked and dismissed Capt. Fauntleroy, who would be killed by a cannonball on his 22nd birthday at the pivotal battle of Monmouth, N.J., in June.

On April 22, Washington picked up a quill pen, dipping it periodically in his inkwell, and composed this letter:

Sir,

Altho’ [Although] I am not much accustomed to accept presents, I cannot refuse one offered in such polite terms as accompanied the pistols & furniture you were so obliging as to send me by Capt. Fauntleroy. They are very elegant & deserve my best thanks, which are offered with much sincerity. The favorable sentiments you are pleased to entertain of me, & the obliging and flattering manner in which they are expressed add to the obligation & I am Sir, Yr [your] Most Obedt [obedient] & Most H: [humble] Serv [servant]

GW

Several days later, he wrote a letter of instruction to Capt. George Lewis:

Dear George,

I should be glad if you would let the enclosed [the thank-you letter to Harry Turner] go by a safe hand as is to thank Mr. Turner for an elegant pair of pistols and furniture which he obligingly made me a present of. I do not know where to direct to him, but believe he lives somewhere on Rappahannock, either near Leeds or above it. He is the son of Harry Turner, and I think married the sister of Captain Fauntleroy. I would not have the letter to miscarry … .

George Washington carried those pistols with him throughout the remainder of the American Revolution. Today, they reside on the second floor of the West Point Museum, featured in “The American Wars” gallery. Some time ago, my friend Larry Spisak and I were given the opportunity and privilege to examine and photograph them. It was an inspirational and educational experience.

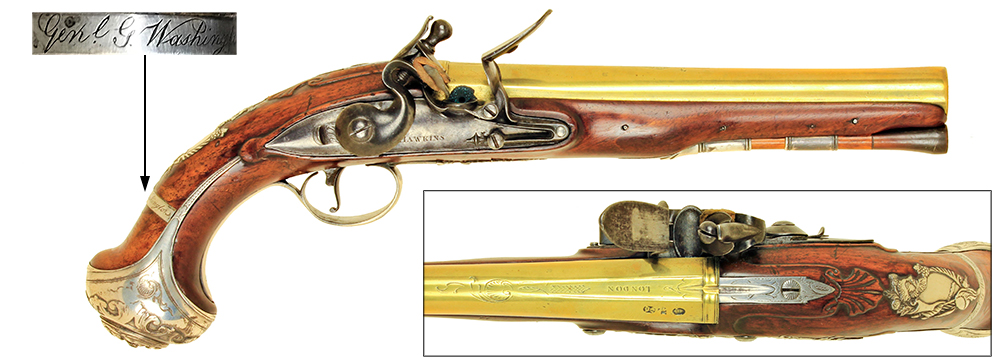

The Washington pistols at West Point are a pair of identical, flintlock, silver-mounted, English pommel pistols (to be carried in holsters over a saddle’s pommel,) 14″ long in total length. The 8″-long, octagon-to-round brass barrels show clear British proofmarks and are stamped with the initials “RW,” which has been determined to be the touchmark for the London gunmaker Richard Wilson. The sideplates display motifs of lions and unicorns. Both of the grips have engraved silver bands with the name: “Gen.l G. Washington.” Hawkins, the name of a gunmaker, also from London, is engraved upon the lockplates. One interesting feature about the locks is that they are equipped with a sliding-tab safety, located underneath and behind the cocking mechanisms. This allows the guns to be safely carried cocked, loaded and primed. Both pistols, ergonomically, felt right at home in the hand and are in good enough condition that I believe they could be safely loaded and fired.

Colonel Thomas Turner, the original owner of the pistols, born in 1696, was a prosperous landowner in Virginia and a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. He ordered them from London sometime in the mid-18th century, and when he died around 1758, left his estate to his grandson, also named Thomas. That’s because young Thomas’ father, Maj. Harry Turner, a clerk for King George County, had died earlier in 1751.

Milton F. Perry, a past West Point Museum curator, wrote in 1955, “Turner was the grandson of Thomas Turner, who died in 1758, and with whom the young Washington was well familiar. … in 1747, 15-year-old Washington played him [the grandfather] at billiards. It cannot be said that the justice (Colonel Turner) was taking advantage of the youth, for he lost a total of thirteen shilling to him. Apparently, Washington visited the (Colonel Thomas) Turner plantation, Walsingham, on the Rappahannock River, not a great distance from Mount Vernon, fairly often, even after the owner’s death.”

Washington owned these pistols into the twilight of his retirement. A few years before he died, however, he presented them as a gift to Bartholomew Dandridge Jr., the nephew of his wife, Martha, and his personal secretary for six years. They were very close friends. In a letter from Philadelphia, dated March 8, 1797, Washington wrote Dandridge:

My Dear Sir,

Your conduct during a six Years residence in my family, having been such as to meet my full approbation & believing that a declaration to this effect would be satisfactory to yourself & justice requiring it from me, I make it with pleasure. And in full confidence that the principles of honor, integrity & benevolence which I have reason to believe have hitherto guided your steps will still continue to mark your conduct, I have only to add a wish that you may lose no opportunity of making such advances in useful acquirements, as may benefit yourself, your friends and mankind. And I am led to anticipate an accomplishment of this wish when I consider the manner in which you have hitherto improved such occasions as have offered themselves to you.

The cares of life on which you are now entering will present new Scenes & frequent opportunities for the improvement of a mind desirous of obtaining useful knowledge, but I am sure you will never forget, that without Virtue & without integrity, the finest talents & the most brilliant accomplishments can never gain the respect or conciliate the Esteem of the truly valuable part of mankind. Wishing you health happiness and prosperity, in all your laudable undertakings, I remain Your Sincere friend & Affectionate Servt [servant]

Go: Washington

After Dandridge died, his estate was put up for auction, and Col. Philip Marsteller, a close friend of Washington and one of six pallbearers at Washington’s funeral, purchased them. Marsteller would eventually will the guns to his son, Samuel. When Samuel passed away, the pistols were bequeathed to his sons, and when they died, their sister, Monnie, became the owner. A family dispute forced the pistols to be auctioned at that time, and the guns were sold to an arms collector named Francis Bannerman for $500. In 1914, they were sold to Edward Litchfield, and he kept them until 1951 when they were sold to a New York millionaire named Clendenin Ryan. It was Ryan who donated the pistols to the West Point Museum.

When Larry Spisak and I arrived at the museum, we were cordially met by Les Jensen, the museum’s curator, who guided us and the photo equipment to the room where we photographed the pistols. It was a bit tricky getting the pistols out of their display case and freed from the very tight security system, but, in the end, we got the images we came for.

In 1976, the United States Historical Society copied and made available 975 commemorative cased sets of the Washington West Point pistols, and they still show up at auctions. The West Point Museum has fabulous exhibits of firearms to view, including a pair of pistols that once belonged to Napoleon.

Handling a pair of pistols that once belonged to our first president seemed to bring me closer to the man and time period, including the struggles at Valley Forge and our War of Independence. I can imagine how they might have looked, holstered and secured to the pommel of Washington’s saddle. They were and are an exceptional work of art and artistry—a gift from a patriotic admirer for an exceptional man: George Washington!