In the early part of the 20th century, the bloody killing fields in France and Belgium were chewing up an entire generation. War in the Industrial Age stole life on a scale previously unimagined. Amidst the fetid trench warfare that characterized that tortuous time, the world’s engineers strived to contrive tools to give their nation’s fighting men an edge on the battlefield.

John Moses Browning was the most gifted gun designer who ever drew breath. Born five years before the American Civil War, Browning held 128 firearms-related patents when finally he breathed his last in Liege, Belgium, in 1926. If we had any sense as a nation (we don’t), we would carve his likeness into a mountain someplace.

John Browning was particularly busy in the early part of the 20th century. He bodged up the 1911 pistol along with the M1917 belt-fed, water-cooled machinegun. Based upon specs purportedly crafted by Black Jack Pershing himself, he also designed the 12.7x99mm/.50 BMG round and the beastly M2 machinegun that fired it.

Though originally intended to defeat WW1-era balloons, variations of Browning’s inimitable Ma Deuce heavy machinegun eventually armed every American combat aircraft of WWII.

He also drew up plans for something radically fresh and new. He called this invention the Browning Machine Rifle.

Was It a Mistake?

The Browning Machine Rifle was based upon a thoroughly discredited concept. Military planners felt that “walking fire” might be a good idea on the modern battlefield. In this hypothetical world, soldiers armed with repeating weapons would stand erect and stride purposefully toward enemy positions firing a round from the hip every time a certain foot hit the ground. Naturally, this idea arose with the French. It turned out that in the real world actual flesh and blood soldiers were none too keen to put this dubious tactic into practice. It did nonetheless still birth a most remarkable firearm.

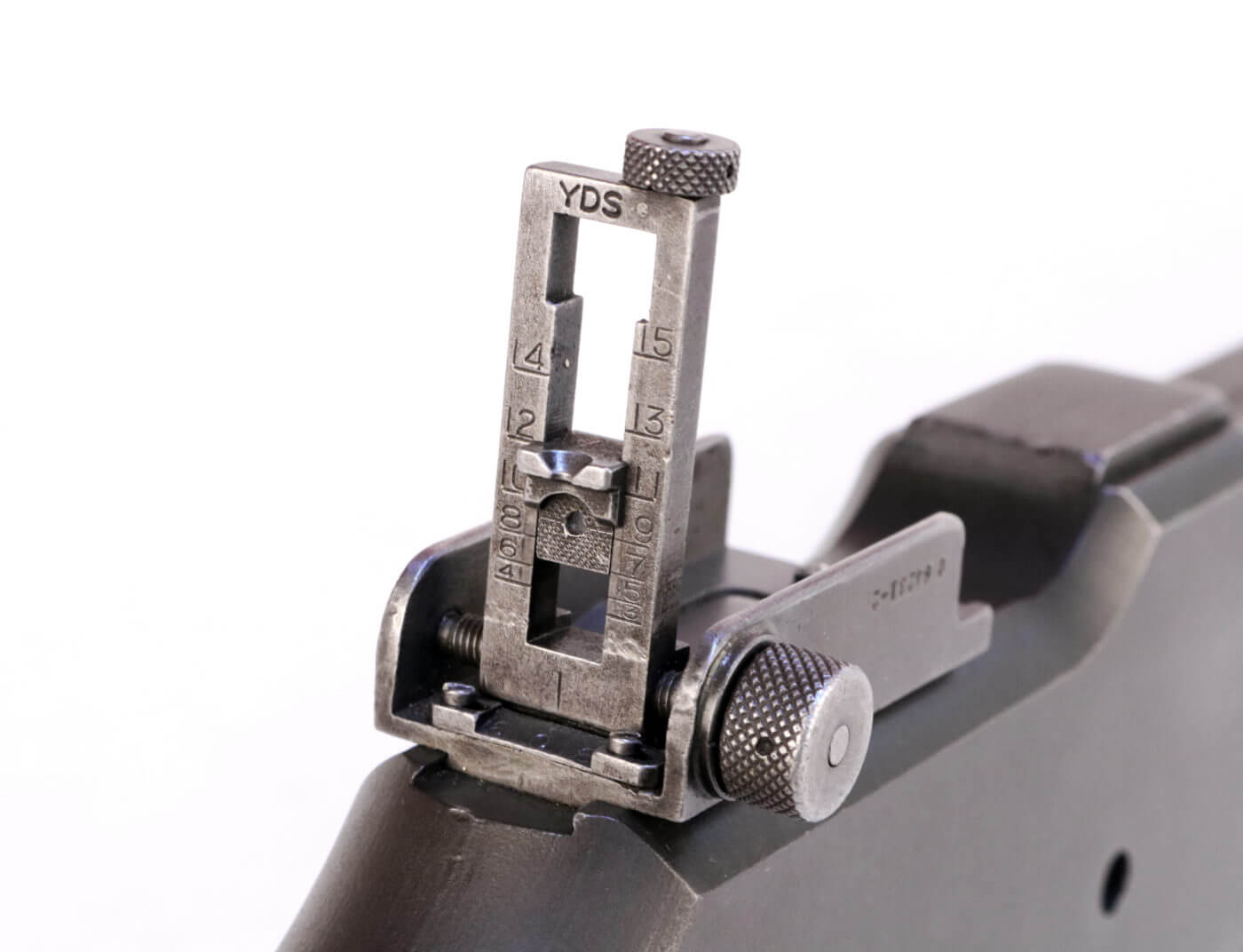

Browning’s Machine Rifle was a monster of a thing that seemed better scaled to David’s Goliath than to normal folk. At 15.5 lbs. and nearly four feet long, the newly christened BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle) was a selective fire beast that fed from 20-round steel box magazines.

Cycling at around 550 rpm on full auto and firing from the open bolt, the BAR offered a quantum improvement over the bolt-action rifles of the day as well as such abominable light machinegun designs like the French Chauchat.

The web gear issued along with those early BAR’s included four double-magazine pouches, a pair of 1911 pouches and a fascinating tin cup scaled to accept the buttstock of the BAR. The theory was that a gunner might lodge the buttstock in this cup and run the gun from the hip as he strolled leisurely toward the Huns’ chattering Maxims. Subsequent WWII-vintage web gear just had six double-magazine pouches and eschewed the cup.

Generations

Some 43,000 early M1918 BARs were shipped to Europe by the end of WWI. Of those, 17,664 were issued to the American Expeditionary Forces, and 4,608 actually saw action. These were the variants that were later stolen by Clyde Barrow from National Guard armories and used on his reign of terror across the American heartland during the gangster era.

A modification dubbed the M1918A1 sort of fizzled, but by 1939 the basic BAR chassis had been upgraded to the M1918A2 standard. A great many earlier guns were arsenal rebuilt into the more modern configuration. A2 upgrades included a bulky folding bipod, a redesigned flash hider, reimagined furniture and fresh entrails. The new three-position selector offered safe, slow and fast options. The cyclic rate on slow was around 350 rpm, while the fast rate was about 550 rpm.

The demand for walnut for rifle stocks threatened to denude American forests, so Firestone Latex and Rubber developed a synthetic substitute for the M1918A2 BAR. These early composite buttstocks were molded from a fabric-reinforced plastic that rendered fine service. Most wartime BARs sported this sort of furniture.

The M1918A2 ultimately weighed 20 lbs., a full 4.5 lbs. more than the original M1918. As a result, a great many BAR men in WWII removed their bipods, monopods and sometimes flash suppressors in an effort at cutting down weight. The carrying handle that affixes around the barrel was adopted very late in the war and didn’t really see service until Korea.

Practical Magic

The BAR is a massive bulky beast that fires a comparably massive 7.62x63mm/.30-06 round. I honestly cannot imagine humping this thing through a fifteen-mile forced march. The leather sling is fairly wide, but the gun remains just huge. I think perhaps those old guys were just tougher than we are today.

2 replies on “THE BAR: A FLAWED FOUNDATION? By Will Dabbs, MD”

Re: “The BAR is a massive bulky beast that fires a comparably massive 7.62x63mm/.30-06 round. I honestly cannot imagine humping this thing through a fifteen-mile forced march. The leather sling is fairly wide, but the gun remains just huge. I think perhaps those old guys were just tougher than we are today.”

As a long-time military historian and historic FA aficionado, I had long-subscribed to the idea that the biggest strongest guys in the squad or platoon were issued BARs. Well, you’re never too old to learn something new, because I have now run across a number of accounts which seem to question that conclusion. It seems that the Germans, Japanese etc. looked for BARs first in the hands of larger soldiers or Marines, so often a different man was issued to weapon. Size played a part, but not the only part. Often, men who qualified as expert on the BAR during training were issued them.

I’ve never had much patience with modern folks complaining about the allegedly ridiculous weight of military-issue firearms. The men of that now distant time of WWI, WWII and Korea carried BARs and M-1s and M1919 medium machine guns into into battle and did just fine. Many of them were small and lightweight men by today’s standards, too. Toughen up, buttercup!

You’ll get a fierce argument from any Brit as to the worth of the Browning Automatic Rifle versus the Bren, to name one contemporary design. The Bren is undoubtedly a superb weapon as the Czechs designed it, but it is well to remember that the Bren was the newer design by a decade or more.

Moreover, it can be argued that they belong to different classes of weapons: The Bren, having a quick-change barrel, was more akin to a true light machine gun. The BAR, on the other hand, had neither a quick-change barrel (not until FN came out with a revised version in the 1950s, anyway) nor the ability to feed belted or linked ammo. Browning’s weapon was a true automatic rifle, not a light or general-purpose machine gun.

Over the many years I’ve spoken with veterans – including many combat veterans – of various wars of the 20th century, whenever the BAR is mentioned, the faces of those old GIs just light up. They smile and then saying something like “Now that was a heck of a weapon…” and then they’ll tell you how the BAR man in their unit saved everyone’s bacon during a fierce fire-fight or something along those lines.

BAR men were often employed in teams by the Marine Corps, who used them to flush out and eliminate Japanese snipers hidden in tree-tops. A rifleman with an M-1 or M1903 would draw fire from a suspected enemy sniper, either by exposing himself briefly or by firing one or two shots into the suspected position. If the hidden enemy replied with fire of his own, the BAR man would engage and knock him out.

In the Korean conflict, one or two BAR positions usually anchored emplaced medium or heavy machine guns, in order to provide fire support when they were down for a barrel change or ran short on ammo. In this manner, positions expecting human wave attacks were never without the coverage of at least some automatic weapons. And since several positions handled these missions, the weapons used had more time to cool occasionally on breaks from long strings of fire.

As far as the original idea of the Browning Automatic Rifle was concerned, “walking fire” was for a time standard U.S. Army doctrine, perhaps not in the field, but in training. Veterans of trench warfare on the western fronr knew that to show one’s head, even for an instant, above the parapet, was to invite a quick death by sniper fire. So, the idea of two or three men comprising a BAR team (a gunner and two ammo bearers and assistants) strolling towards German lines while firing the weapon ended up being a non-starter.

However, the American Expeditionary Force did see Val Browning, John Browning’s son and a U.S. Army junior officer, engage in field training of the men using the weapon his father invented. Photographs survive today documenting this fact.

The concept of “walking fire” was flawed, to be sure, at least for clearing trenches during WWI, but it did prove useful in teaching men how to control the weapon. Specifically, by carrying it slung at waist-height and braced against one’s side or hip. It could also be fired accurately from the shoulder, and from the prone position.

The weight of the weapon, 15 or more lbs. loaded, helped tame the substantial recoil from the powerful 30-06 cartridge the weapon fired. Sometimes, maybe not too often, weight is the soldier’s friend. Various nations in NATO later learned the folly of trying to turn an ordinary infantry rifle of 7-9 lbs. or so into an automatic weapon while firing a full-power rifle cartridge. John Browning was a genius, yes he was…. the man knew what he was doing.