George Cook had never thought much about guns until about four years ago. Then he grew older and got married, and felt like he had a lot more to protect.

So he bought a handgun. And last year, at the height of social justice protests and scattered violence, he bought an AR-15. During the pandemic, first-time gun owners spurred record levels of gun sales for what looks like the second year in a row, with uncertainty, political polarization, and a spike in shootings around the country cited as reasons for the buying spree.

Today, Mr. Cook goes a few times a year to the range to shoot his firearms. Aside from that, neither weapon ever leaves his house. He figures about half the houses on his street on the Richmond, Virginia, outskirts have guns in them. He cites suburban values as one reason he bought a gun.

“It’s easy to measure how bad guns can be for sure,” says Mr. Cook, who works as a corporate treasury analyst. “You can look at all the deaths, the mass shootings. But it’s not easy to measure the bad that they prevented.”

Those values are notable in another way: Like other suburban gun owners, Mr. Cook says he is open to at least some regulation, particularly those focused on gun safety. Interviews with suburban gun owners underscore how U.S. gun culture is becoming more diverse, more nuanced, and increasingly focused on the personal responsibility of individuals who choose to own a gun.

In 2020, the U.S. saw the largest number of gun-related deaths – 19,000 – in almost two decades. This spring has also seen a resurgence of mass shootings (defined as four or more people killed), which had paused during pandemic lockdowns: The March 16 mass shooting in Atlanta, where eight people were killed, was followed quickly by three more, including in a Boulder, Colorado, supermarket and an Indianapolis FedEx facility.

In response, the Democratic-led House passed legislation that would require background checks for all gun buyers and extend the time that the FBI has to conduct those checks. A majority of gun owners support both ideas. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer has vowed to bring a package to the Senate as early as May, but Republican support is considered unlikely.

Whether the engagement of suburban gun owners like Mr. Cook in the debate over gun safety is enough to break gridlock in Washington is far from certain. Guns, after all, are deeply embedded in America’s polarized identity politics.

But the emerging focus on gun safety “is really an important effort,” says Adam Winkler, author of “Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America.” “We can talk about gun control and gun regulation until we’re blue in the face, but there’s always going to be a lot of guns in America. They are here to stay. … [But] many of our gun problems can be lessened or reduced by responsible gun ownership.”

The image of a typical gun owner is a white man, usually conservative, who lives in the country.

Yet most American adults have shot a gun at least once: 72%, Pew found in 2017. And nearly half of all non-gun owners said they would consider owning a gun in the future.

Increasingly gun owners are represented by more suburban groups like the Pink Pistols, Liberal Gun Owners, and blogs like Gun Culture 2.0, run by a gun-toting college professor in North Carolina. Polls have found that a majority of gun owners favor stronger gun regulations, as long as the basic right of gun ownership is respected.

Part of the reason is that suburban Americans who used to never think about gun violence are now thinking about it “too much,” as one suburban woman told the Cook Political Report in a wide-ranging focus group last year. Yet for many of those worried about violence, the answer isn’t necessarily fewer guns.

Dan Gross has long understood that paradox. His brother was shot in the head and permanently disabled in a mass shooting at the Empire State Building in 1997. The former head of the Brady Campaign has worked for years to enact stronger gun laws, but always, he says, with a sense of empathy for law-abiding gun owners.

He says his support for gun ownership hasn’t changed – he’s just become more outspoken on how to actually reduce gun violence. He has criticized President Joe Biden for calling for an assault weapons ban, given that it only riles up Second Amendment supporters and, more importantly, fails to acknowledge that assault rifles are rarely used in homicides. Just 1% of gun-related deaths are “active shooter” situations, compared with 30% that are homicides. Instead of trying to ban certain guns from all people, he says the focus should be on how to keep all guns away from certain people, such as stronger red flag and background check laws.

Meaningful change, says Mr. Gross, means changing the entire conversation from one defined by politics to one defined by common values and goals, specifically, protecting the community. Speaking in front of a potentially unfriendly Second Amendment rally in Washington, D.C., in 2019, he saw evidence that it could work.

“I start to get momentum and people are applauding …,” says Mr. Gross. “And there’s a guy toward the front, and he was the one guy that, [stereotypically] if I should be scared of someone, it’s that person. And when I said, ‘Now, we may not agree on everything,’ that’s the guy who screams out: ‘That’s OK!’”

A focus on respect and responsibility rings true to Jeff Kelman of New Hampshire.

Mr. Kelman grew up in a progressive Massachusetts home, the son of two mothers. He had no idea people could even own guns until he was in middle school. But after college, he started shooting for sport – and developed a sharp eye.

As a Jewish man whose wife is Chinese American, he is keenly aware of racial discrimination in the U.S., and the potential for that to turn into violence. So, he carries a gun for self-defense.

Instead of lining up his views ideologically, Mr. Kelman prefers to approach the issue as a cost-benefit analysis. Gun control laws have the potential to save lives, but also come at the cost of personal freedom. In that analysis, everyone has a different threshold.

“If you’re going to have an armed society, you almost need to have a ubiquitously armed society,” he says. “Alternatively, if you have a society that isn’t going to take up this act and they’re going to delegate that to the police and the military … then again, both of those societies will be, I think broadly, fairly safe.”

The more it becomes a “patchwork,” he says, the less it makes sense.

Some sense that suburban gun owners present a unique opportunity for pragmatic change. Nestled between rural areas where lots of people hunt and cities where most gun violence occurs, the suburbs offer a sense that “the old patterns or the old methods aren’t working very well,” and a growing frustration that “we’re not getting anywhere in the gun violence prevention debate right now,” says Professor Winkler at the University of California, Los Angeles.

But others think their overall influence would be marginal, at best.

“It’s not clear, as a separate political force, how much impact [suburban gun owners] would have outside of a ticking up in public opinion polls support for stronger gun laws,” says Bob Spitzer, author of “The Politics of Gun Control.”

Anecdotally at least, Tom O’Connor, who sits on the board of Gun Owners for Responsible Ownership, finds gun owners in those expanding areas more pragmatic than traditional gun owners. That expresses itself, he says, in their support for universal background checks, red flag laws, and requirements for safe storage.

Rights, after all, change over time, says Mr. O’Connor. And if the public doesn’t support absolute access to firearms, that access could be curtailed. “It’s clearly something we have to deal with,” he says.

Mr. Cook, the Richmond suburbanite, says values, culture, and identity complicate the search for compromise. After all, he says, people use guns in so many different ways across the U.S., whether for hunting, sharp-shooting, or protection.

Yet he has felt his own attitudes shift. “The more things [like mass shootings] happen, the more my views change,” he says. “I’m not set in stone in my ways. I still think guns should be legal, and yet I’m definitely deeply affected by this. It makes me second-guess myself.”

Editor’s note: A clarification has been made indicating that Jeff Kelman began shooting for sport after college.

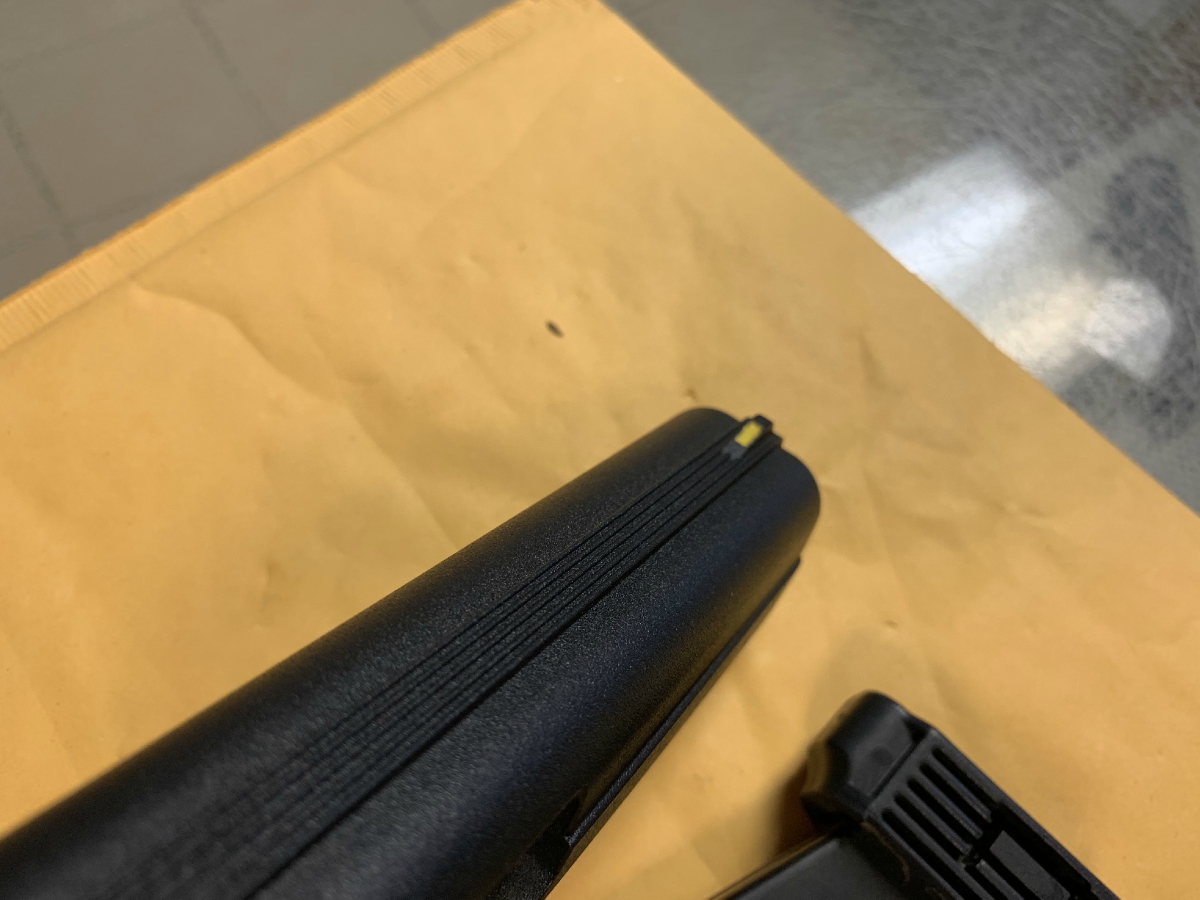

The Hi-Point handguns are +P rated and accept all factory ammunition.

Brand Hi-Point Category Pistols Caliber 45 Automatic Colt Pistol (ACP) Model 45 ACP Series Standard Type Pistol Frame Finish Black Action Double Slide Description Black Capacity 9+1 Frame Material Polymer Grips Black Polymer Safety Manual Sight Configuration. With a 3-Dot Adjustable Sight Style Adjustable Weight 35 oz Barrel Length 4.5

So, the day after Christmas 2020, I filled out the application, paid the $55 course fee, and passed the online handgun safety course required for the license. I knew that skyrocketing demand meant I was in for a much longer wait time than normal, and so I chuckled slightly and just sort of accepted it when the system told me my appointment to get my license would be in April 2021.

In the interim, my family and I had decided to move to Florida after the current school year ends. We became occupied with house-hunting, packing, selling a second property, and arranging contractors to make repairs to get our main home on the market. A whole series of columns will follow detailing why we decided to bail on Oregon, but suffice it to say that the kids needed real school, our entire family needed relief from pandemic fascism, and we have grown weary of big-city life.

This will become important in a moment.

Again, I had no real sense of urgency, and I’ve gone this long without my concealed handgun license, so I didn’t sweat the wait too much. It did make me wonder, though, what if you’re in a higher-crime neighborhood watching the crime rate skyrocket throughout Portland, as response times increase in direct proportion to how much city council has defunded the police? What if you’re in an abusive relationship, need a restraining order, and know that the police can’t protect you? What if you are worried about exploding gang violence? Any number of scenarios could give a Portland resident pause to consider carrying a handgun.

Anyway, my appointment rolled around on April 21 at 11 a.m. I showed up at the Penumbra Kelly Building, home of the Multnomah County Sheriff’s Office (MCSO), a few minutes early. Even though I’ve lived through nightly riots in Portland, I was still taken aback at the appearance of the building. Plywood covering EVERYTHING. I walked in, and the lobby was completely unlit. I looked up and saw plywood covering all the windows.

It looked like the working definition of dystopia.

I took their COVID-19 quiz and had my temperature taken. After a few minutes, the two ladies who process the paperwork arrived. Since I had arrived first, I was up. I walked into the little room to get my picture taken, get fingerprinted, etc.

We made small talk: “Boy, you guys are backed up, huh?”

“Yeah,” one of them replied, “it’s been pretty busy.”

“Seems like a nice place to work, at least, with all the plywood …” That engendered a snicker from both.

Related: Gun Sales in U.S. Set New Records in January, Fresh Off Huge Sales In 2020

The one lady finished taking my digital fingerprints, and the other took my $65 license fee. I was now into this thing for $120, the cost of the exam and the fee for the license. Next up, they took my picture for my concealed handgun license.

I got my receipt, my ID, and my certificate of course completion back. What the clerk said next caused me to double-take, as if I hadn’t heard her correctly.

“Ok now, this is not a license.”

“I—I’m sorry?”

“This is not a license. You won’t be receiving your license today.”

This, as you may imagine, was news to me.

“Yeah,” she said to me, “we still have to run the background check, and process your paperwork.”

I blinked back at her, disbelievingly.

“It could be up to 90 days.”

Now, mind you, I’ve legally purchased an undetermined amount of firearms in the not-so-distant past (all of which, I must reiterate, I tragically lost in a boating accident). When things got super busy, around Christmas time, my background check took up to an hour or two.

The MCSO told me that the entire process, from application, to safety certification, to license issue, will stretch from December 2020 to around July. Eight months.

Good thing Portland hasn’t given anyone a reason to need a concealed handgun over the past year and a half.

Remember, I had decided in the interim to pack my family up and move to Florida. This will happen sometime in June. Here’s the ironic thing. It’s almost certain that my new Oregon concealed handgun license will need to be forwarded to my new address out of state if and when it is finally issued. It’s also entirely possible that I will get my Florida license well before my Oregon license arrives.

A few things have run through my head about this whole ordeal. One: I know this is liberal deep-blue Portland. The clerks in the office reported, however, that they’ve seen unprecedented demand. The number of customers in the lobby confirm this, and the clerks also tell me they have appointments all day, every day. There must be thousands of Multnomah County residents applying for concealed handgun licenses, for myriad obvious reasons.

Two, and much more sinister: the conspiracy part of my brain can’t believe the Multnomah County Sheriff hasn’t used the pandemic and the nightly riots and the exploding demand as excuses to slow-walk CHL applications. That’s just how the politics of this county work.

A variety of forces have converged to make acquiring your concealed handgun license in Portland as onerous as possible. Just another in the pile of reasons to move out of Multnomah County and migrate to somewhere that doesn’t make it so difficult.