Yesterday was one of those few greater days of my life. In that I had some time, the money and the opportunity to buy almost any gun that I wanted.

(The Best days being when I first met my Wife or when my Son gave me a Granddaughter)

So off I went to one of the local Gun / Pawn Shops in the area. Where I was able to buy after a modest amount of haggling. A used P-226 in 9mm in the box.

Now dear Reader, here is why I brought this hand cannon. As I figured that since my P-220 in 45 ACP was an absolute Champion of a hand gun. That and my Beretta 92f was kind a lonely too..

Plus I am told that the Seals and a bunch of other hard nose types liked them & whom am I to disagree with them? Right!?!

So I figured why not & so handed over the cash with all the various ID crap that this crazy state requires. So that I can exercise my 2nd Amendment rights.

Now for the bad news, in that I am a citizen / prisoner / inmate of the Peoples Republic of California.

I now have to wait until the 9th of January 2019 to gain possession of my property.

Plus we have just elected a very anti Gun Governor & Legislation. All of whom have never met a Tax or Anti Gun Bill that they do not adore. God help us out here is all that I can say!

https://youtu.be/OKyTZXxGoAw

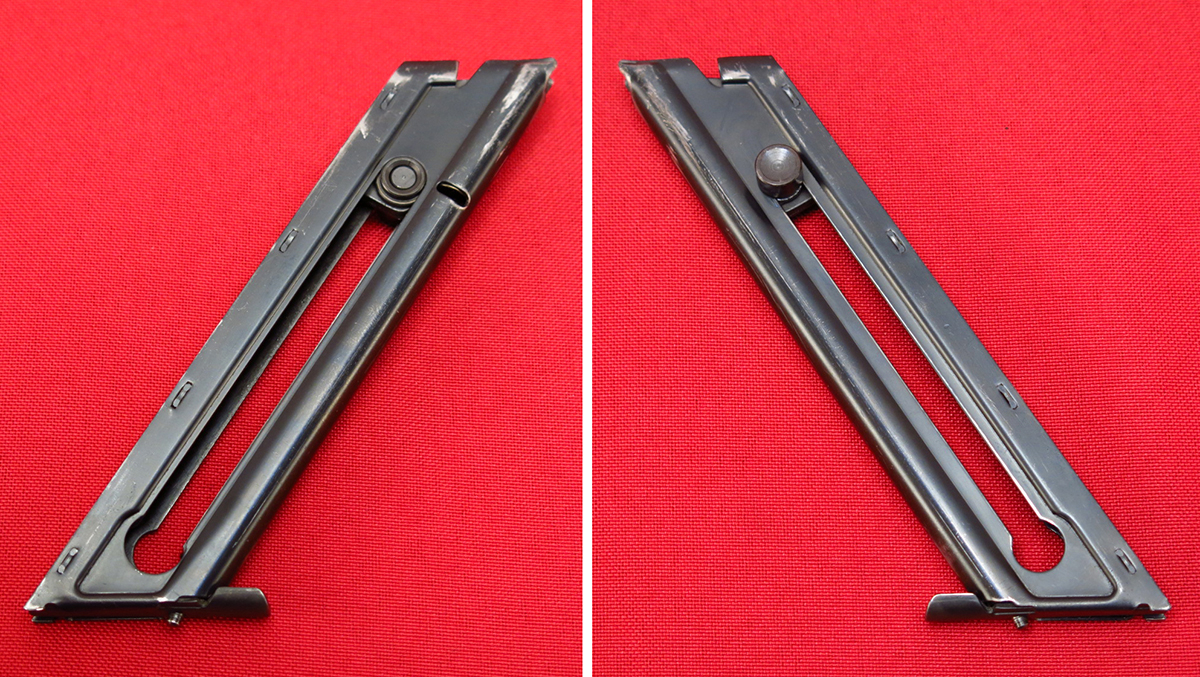

Anyways here is what my future P-226 looks like for those folks who have not had the privilege of seeing one before!

I also wish I had that many magazines come with the deal. But sadly no and to make it more irradiating. I can only had 10 round magazines out here in La La land!

I also wish I had that many magazines come with the deal. But sadly no and to make it more irradiating. I can only had 10 round magazines out here in La La land!

This was Winchester’s Ultimate Plinking Rifle for 22 Long Rifle. They never made money on them. I frankly think that they did this for Ego reasons and I am grateful for it.

So if you want the absolute top of the line American made 22 Rifle. Then frankly I hold that this is the piece for you!

| Winchester Model 52 rifle | |

|---|---|

1954 Winchester Model 52C

|

|

| Type | Rifle |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Production history | |

| Designer | T.C. Johnson, Frank Burton, A. F. Laudensack |

| Designed | 1918-19 |

| Manufacturer | Winchester Repeating Arms Company |

| Produced | 1920-1980 |

| No. built | 125,419 |

| Variants | Sporting Model, International Match |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | 9 lb (4.1 kg) to 13 lb (5.9 kg) target; 7.25 lb (3.3 kg) sporter |

| Length | 45 in (1,100 mm) target; 41 in (1,000 mm) sporter |

| Barrel length | 28 in (710 mm) target; 24 in (610 mm) sporter |

|

|

|

| Cartridge | .22 Long Rifle |

| Action | Bolt-action |

| Feed system | 5 round/10 round box magazine |

| Sights | Micrometer ladder rear sights, fixed-post front sights standard; many custom iron and optical combinations |

The Winchester Model 52 was a bolt-action .22-caliber target rifle introduced by the Winchester Repeating Arms Company in 1920. For many years it was the premier smallbore match rifle in the United States, if not the world. Known as the “King of the .22’s,” the Model 52 has been called by Field & Streamone of “the 50 best guns ever made” and by Winchester historian Herbert Houze “perfection in design.” However, by the 1970s the World War I-era design was showing its age and had given way in top-level competition to newer match rifles from Waltherand Anschütz; the costly-to-produce Model 52, which had long been a loss leader prestige product by that time, was finally discontinued when US Repeating Arms took over the manufacture of Winchester rifles from Olin Corporation in 1980.

[hide]

During World War I Winchester’s management determined that production of the Model 1885 Single Shot would not be resumed in centerfire chamberings after the war, nor in .22 rimfire (the “Winder musket“) after existing Army training rifle contracts were fulfilled or cancelled. A new .22 would therefore be needed for the then very popular sport of target shooting; Winchester reasoned that returning soldiers would be drawn to the bolt action design with which they had become familiar. The rifle to be designated the Model 52 was designed from the ground up as an “accuracy rifle” — the world’s first production .22 to be so conceived. It was initially hoped that the Army could be persuaded to buy a bolt-action smallbore training rifle in addition to-or in place of-its existing contracts for Model 1885’s. Yet despite the outward appearance of its early versions, the Model 52 was never a military rifle, as the Army only purchased 500 of the initial production for trial, and never placed a bulk order.[1]

In February 1918 the company assigned designers Thomas Crosley Johnsonand Frank Burton to begin work on the new match rifle. Johnson had more experience with bolt actions than most at Winchester (which was then primarily a maker of lever- and pump-action firearms), having superintended production of the P-14/M1917 Enfield, as well as having designed a series of prototype military rifles known as Models A through D.[2] Johnson quickly obtained approval for a receiver based closely on that of the Model D, together with a barrel adapted from the .22 target version of the Model 1885. The stock from the receiver back was modeled on that of the Model D, which in turn had been derived from the Model 1895 Winchester-Lee; but incorporated a forearm based on a custom Single Shot target stock designed in 1908 by Winchester’s house marksman, Capt. Albert F. Laudensack.[3]

Patent drawing of Johnson and Burton’s revised magazine-fed action

With the externals settled, Johnson and Burton turned to developing the action for what was now “Experimental Design No. 111.” Each built a prototype of his own design in Winchester’s Model Shop, both at this stage still single-shot. In the fall of 1918 the project’s requirements were changed to include a detachable 5-round box magazine: neither Johnson’s nor Burton’s original bolts would work with a magazine feed, but a combination incorporating elements of both proved highly satisfactory. A finalized repeater prototype was made in April 1919 and taken to Washington where it was evaluated by Lt. Col. Townsend Whelen of the General Staff, Director of Civilian Marksmanship Maj. Richard LaGarde, and Gen. Fred Phillips of the National Rifle Association, who were enthusiastic–—- although guarded about the prospects of a Government contract.

Whelen further recommended that pre-production samples be rushed out in time for the National Matches [1] at Caldwell, New Jersey that August. Six “G22R” prototypes were readied, and equipped five individual event winners and the victorious U.S. Dewar Cup team: the new Winchester was the talk of the tournament. Accordingly, full production as Model 52[4] was authorized on 11 September 1919 and commenced in April 1920 (using the lines and machinery originally installed to produce the P-14/M1917 Enfield).[5]

The Model 52 was a non-rotating, rear-locked bolt-action design. The Model D-derived receiver was cylindrical, bored and machined from a forged billet, and of substantial thickness. The bolt’s dual locking lugs were part of the rotating bolt-handle collar, which provided a camming action to seal the breech on closing and extract the spent case on opening. The bolt itself was undercut for the forward third of its length and rode on polished flats; a projecting lug at the front edge caught the top cartridge in the magazine. The bolt face was rebated so as to surround the case rim, and was chamfered to fit the recessed receiver ring. Dual-opposed sprung claw extractors were inlet into the sides of the bolt, providing controlled cartridge feed. A fixed blade-type ejector was located at the rear of the loading platform.

The original Johnson trigger mechanism, a two-stage or compound-motion military type derived, again, from his Model D, made use of a horizontal sear pivoted from the front; the trigger fit vertically through a pinned mortise in the sear and was shaped at the top so as to cam against the underside of the bolt and depress the assembly, releasing the firing pin; it was a cock-on-closing design. The one-piece striker terminated in a Springfield-like knurled cocking-piece. The wing safety was mounted on the left side of the receiver; when engaged it physically blocked the cocking-piece and cammed it slightly rearward, disengaging the trigger linkage.

The Model 52 went through many alterations over its sixty years. These changes were not systematic: improvements to the action, stock and so on were made on an ad hoc basis, and it is clearer to treat these alterations so separated rather than as “models.”

- Note on serial numbers and sub-model or “Style” letter designators: It was Winchester’s practice to stamp each receiver with its serial number after milling and preliminary polishing, often weeks or months before the rifle was actually assembled. Accordingly, the alphabetic SN suffixes A, B, C and D were applied specifically to changes to the receiver forging itself, originally as an aid to factory workers: not to new designs of stock, furniture or even trigger mechanism if no change to the receiver was required. Other design changes might coincide in time with a receiver ‘submodel,’ or first appear in the same catalog: many commentators have been confused by this, talking about such things as the “Model 52B stock” which, strictly speaking, did not exist. From beginning to end the barrels were marked “Winchester Model 52” without a letter. Winchester catalogs and advertising literature did not mention letter designators until the 1950s.

- Notwithstanding the foregoing, the Model 52D represented a comprehensive upgrade of the entire rifle.

All Model 52’s with iron sights were equipped with receiver-mounted aperture sights, never barrel mounts, tang mounts or open sights.

Because at the time the Model 52 was developed many Army- and National Rifle Association-sponsored matches were restricted to “military-style” sights, and because Winchester had hopes of selling the 52 to the War Department as a marksmanship training rifle, Burton and Laudensack designed a folding ladder sight for the new target rifle. Designated 82A, it bore some resemblance to the sight on the M1903 Springfield, especially in its pivoting-base windage adjustment (albeit controlled by dual-opposed thumbscrews rather than the Springfield rack-and-worm). However, elevation adjustment was governed by a micrometer click-wheel for precision, not free-sliding like genuine military sights. The Burton-Laudensack helped Model 52 shooters sweep matches and set records throughout the 1920s, but more precise aftermarket sights took over the field and the increasingly obsolescent 82A was not offered after World War II.

Winchester catalogs from the beginning listed 52’s with sights by other makers; indeed, the buyer could specify any compatible peep on a special-order basis. The most common of these was the Lyman 48 series: the 48-J and -JH for flat-top dovetail-mount receivers, and the 48-F and -FH for round-top side-mount rifles (standard on the 52 Sporting Model). Other popular sights were the Lyman 525, the Wittek-Vaver 35-MIELT, the Marble Goss 52, and the Redfield 90 and 100. Late 52’s frequently were fitted with Redfield “Olympic” or “International” match sights.

The stock Winchester 93B front sight was an undercut blade type; aftermarket rear sights were typically paired with a compatible globe sight such as the Lyman 17A (except for the Sporter, on which a hooded Lyman or Redfield Gold Bead front sight was standard).

Barrel-mounted scope blocks were optional on early-production 52’s; they were made standard in 1924. These blocks were mounted 6.2″ apart, giving 1.2″ per minute-of-angle graduation at 100 yards. Originally the Winchester A3 and A5 as well as Lyman scopes were offered. In 1933 new bases with Fecker notches were introduced, using standard 7.2″ (1″/MOA) spacing; these were compatible with any normal telescopic sight. Long-barrel Fecker, Unertl and Lyman Targetspot were popular telescopes for prewar Model 52 target rifles, with Redfield and Bausch & Lomb becoming ascendant in the 1950s. The late-70s 52E had additional mounting holes drilled in the forward receiver ring.

Sporting Models were not factory fitted for telescopic sights (except by special order) until 1953, when 52C Sporter receivers (not barrels) were provided with tapped and plugged screw holes. However, many earlier examples were so equipped by private gunsmiths: nearly all the popular hunting scopes have been mounted at one time or another. A period-correct scope is not considered by collectors to detract significantly from the ‘originality’ of a vintage Sporter.

Around 1931 Major John W. Hessian, a friend of new Winchester president John M. Olin,[8] had a private gunsmith remount his Model 52 in a custom lightweight “sporting” stock. Olin was so impressed that he ordered the development of a 52 Sporter as a production model, which made its debut in 1934.

The Sporting Model had a lightweight 24-inch barrel and an elegant gloss-finished stock of figured walnut with a slender, tapering capped forearm, pronounced pistol grip, high comb and cheekpiece, and fancy checkering. The action was identical with contemporary[9] target models, except that the receiver top was left round rather than milled flat. Weighing only 7-1/4 pounds, it came with Lyman 48-F aperture sights standard, and retailed for the substantial sum of $88.50 (the equivalent of nearly $1520 in 2012).

The Sporter was in all respects a deluxe rifle. While Winchester already had a reputation as the Cadillac of American arms manufacturers, the 52 Sporter was produced with a degree of fit and finish appropriate to a custom gunsmith’s shop. Esquire magazine called it “the piece de resistance of all sporting rifles. It’s a diamond in a field of chipped glass– the rifle for the connoisseur.”[10] Field & Stream named the 52 Sporter one of the “50 Best Guns Ever Made,” calling it “unrivalled in beauty and accuracy.”[11]

Understandably the Sporter represented only a small percentage of Model 52’s produced between 1934 and its discontinuation in 1959: it is today the most collectible of all 52 variants and a good Sporter will generally bring double or more the price of a comparable Target. (This market reality has unfortunately attracted forgers, and fake “Sporters” converted from target models have fooled the unwary).

In the 1990s the Herstal Group, owner of Winchester’s trademarks as well as the Browning Arms Company, marketed “reissue” Model 52s in both Target and Sporting models. These reproductions were made by Miroku in Japan, and sold under both the Winchester and Browning brands.

By Maj. John L. Plaster, USA (Ret)

RECON COMPANY AT COMMAND AND CONTROL CENTRAL

In 1968, Robert L. Howard was a 30-year-old sergeant first class and the most physically fit man on our compound. Broad-chested, solid as a lumberjack and mentally tough, he cut an imposing presence. I was among the lucky few Army Special Forces soldiers to have served with Bob Howard in our 60-man Recon Company at Command and Control Central, a top secret Green Beret unit that ran covert missions behind enemy lines. As an element of the secretive Studies and Observations Group (SOG), we did our best to recon, raid, attack and disrupt the enemy’s Ho Chi Minh Trail network in Laos and Cambodia.

UP THERE WITH AMERICA’S GREATEST HEROES

Take all of John Wayne’s films—throw in Clint Eastwood’s, too—and these fictions could not measure up to the real Bob Howard. Officially he was awarded eight Purple Hearts, but he actually was wounded 14 times. Six of the wounds, he decided, weren’t severe enough to be worthy of the award. Keep in mind that for each time he was wounded, there probably were ten times that he was nearly wounded, and you get some idea of his combat service. He was right up there with America’s greatest heroes—Davy Crockett, Alvin York, Audie Murphy, the inspiring example we other Green Berets tried to live up to. “What would Bob Howard do?” many of us asked ourselves when surrounded and outnumbered, just a handful of men to fight off hordes of North Vietnamese.

To call him a legend is no exaggeration. Take the time he was in a chow line at an American base and a Vietnamese terrorist on a motorbike tossed a hand grenade at them. While others leaped for cover, Howard snatched an M-16 from a petrified security guard, dropped to one knee and expertly shot the driver, and then chased the passenger a half-mile and killed him, too.

One night his recon team laid beside an enemy highway in Laos as a convoy rolled past. Running alongside an enemy truck in pitch blackness, he spun an armed claymore mine over his head like a lasso, then threw it among enemy soldiers crammed in the back, detonated it, and ran away to fight another day.

Another time, he was riding in a Huey with Larry White and Robert Clough into Laos, when their pilot unknowingly landed beside two heavily camouflaged enemy helicopters. Fire erupted instantly, riddling their Huey and hitting White three times, knocking him to the ground. Firing back, Howard and Clough jumped out and grabbed White, and their Huey somehow limped back to South Vietnam.

CONSIDER THE RESCUE OF JOE WALKER

“Just knowing Bob Howard was ready to come and get you meant a lot to us,” said recon team leader Lloyd O’Daniels. Consider the rescue of Joe Walker. His recon team and an SOG platoon had been overrun near a major Laotian highway and, seriously wounded, Walker was hiding with a Montagnard soldier, unable to move. Howard inserted a good distance away with a dozen men and, because there were so many enemy present, waited for darkness to sneak into the area. Howard felt among bodies for heartbeats, and checked one figure’s lanky legs, then felt for Joe’s signature horn-rimmed glasses. “You sweet Son of a Gun,” Walker whispered, and Howard took him to safety.

What’s all the more remarkable is that not one of these incidents resulted in any award. Howard was just doing what had to be done, he thought.

“HOPELESS” WAS NOT IN HIS VOCABULARY

Unique in American military history, this Opelika, Alabama native was recommended for the Medal of Honor three times in 13 months for separate combat actions, witnessed by fellow Green Berets. The first came in November 1967. While a larger SOG element destroyed an enemy cache, Howard screened forward and confronted a large enemy force. He killed four enemy soldiers and took out an NVA sniper. Then, “pinned down…with a blazing machine gun only six inches above his head,” he shot and killed an entire NVA gun crew at point-blank range, and then destroyed another machine gun position with a grenade. He so demoralized the enemy force that they withdrew. This Medal of Honor recommendation was downgraded to a Silver Star.

The next incident came a year later. Again accompanying a larger SOG force, he performed magnificently, single-handedly knocking out a PT-76 tank. A day later he wiped out an anti-aircraft gun crew, and afterward rescued the crew of a downed Huey. Repeatedly wounded, he was bleeding from his arms, legs, back and face, but he refused to be evacuated. Again submitted for the Medal of Honor, his recommendation was downgraded, this time to the Distinguished Service Cross.

Just six weeks later, Howard volunteered to accompany a platoon going into Laos in search of a missing recon man, Robert Scherdin. Ambushed by a large enemy force, Howard was badly wounded, his M-16 blown to bits—yet he crawled to the aid of a wounded lieutenant, fought off NVA soldiers with a grenade, then a .45 pistol, and managed to drag the officer away. Having been burned and slashed by shrapnel, we thought we’d never see him again. But he went AWOL from the hospital and came back in pajamas to learn he’d been again submitted for the Medal of Honor. This time it went forward to Washington, with assurances that it would be approved.

Howard did not know the word, “hopeless.” Many years later he explained his mindset during the Medal of Honor operation: “I had one choice: to lay and wait, or keep fighting for my men. If I waited, I gambled that things would get better while I did nothing. If I kept fighting, no matter how painful, I could stack the odds that recovery for my men and a safe exodus were achievable.”

Although eventually sent home, he came back yet again, to spend with us the final months before his Medal of Honor ceremony. By then he had served more than 5 years in Vietnam. Why so much time in Vietnam? “I guess it’s because I want to help in any way I can,” Howard explained. “I may as well be here where I can use my training; and besides, I have to do it – it’s the way I feel about my job.”

THE WARRIOR TRADITION

The warrior ethic came naturally to Bob Howard. His father and four uncles had all been paratroopers in World War Two. Of them, two died in combat and the other three succumbed to wounds after the war. To support his mother and maternal grandparents, he and his sister picked cotton. He also learned old-fashioned Southern civility, removing his hat for any lady and answering, “Yes, ma’am.”

He also possessed a deep sense of honor and justice, and lived by his unspoken warrior’s code, with the priorities mission, men, and his own interests coming last. He absolutely fit the bill as a leader you’d follow through hell’s gates – IF you could keep up with him. A hard-charging physical fitness advocate, he even had our Montagnard tribesmen running and doing calisthenics.

After draping the Medal of Honor around Howard’s neck, President Nixon asked him what he wanted to do the rest of that memorable day – lunch with the president, a tour of the White House, almost anything. Howard asked simply to be taken to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier to share his thoughts with others who had gone before him. Tragically, the U.S. media, reflecting the anti-war sentiments of that period, said not one word about Howard or his valiant deeds, although by the time he received the Medal of Honor he was America’s most highly decorated serviceman.

HIS FRAME OF REFERENCE WAS SOG—HARD COMBAT

Despite the lack of recognition, Howard went on serving to the best of his ability. He was the training officer at the Army’s Airborne School, then he was a company commander in the 2nd Ranger Battalion at Ft. Lewis, Washington. He continued to excel at everything he did, making Distinguished Honor Graduate in his Officer Advance Course class.

As the officer-in-charge of Special Forces training at Camp Mackall, near Ft. Bragg, N.C., and later, commanding the Mountain Ranger Training Camp at Dahlonega, Georgia, he did his utmost to inspire young students. Howard’s frame of reference was SOG—hard combat, the toughest kind against terrible odds with impossible missions. He knew good men would die or fail in combat without martial skills, tactical knowledge and physical conditioning. He was famous for leading runs and long-distance rucksack marches— stronger than men half his age, usually he outran entire classes of students. A whole generation of Army Special Forces and Rangers earned their qualifications under his shining example, with some graduates among the senior leaders of today’s Special Forces and Ranger units.

His highest assignment was commander of Special Forces Detachment, Korea. He might have gone higher but he dared to publicly suggest that American POWs had been left in enemy hands, and was willing to testify to that before Congress in 1986. After he retired as a full colonel, he went through multiple surgeries to try to correct the many injuries he’d suffered over the years.

But he could not stop helping GIs. He spent another 20 years with the Department of Veterans Affairs, helping disabled vets. He had a reputation for rankling his superiors as an unapologetic advocate of veterans.

THIS HUMBLE KNIGHT BELONGS TO HISTORY

His spirit never waned. In 2004 I sat with Green Berets of the 1st Special Forces Group at Ft. Lewis, Wash., who laughed and cheered when he joked about still being tough enough to take on any two men in the audience—not one raised his hand. After retiring from the VA, Col. Howard often visited with American servicemen to speak about his combat experiences, making five trips to Iraq and Afghanistan. In the fall of 2009, he visited troops in Germany, Bosnia and Kosovo.

Despite increasing pain and sickness, on Veterans Day 2009 he kept his word to attend a memorial ceremony, but finally he had to seek help. He was diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer and given a few weeks to live.

In those final days old Special Forces and Ranger friends slipped past “No Visitors” signs to see him. When SOG vets Ben Lyons and Martin Bennett and a civilian friend, Chuck Hendricks, visited him, Howard climbed from his bed to model the uniform jacket he would be buried in, festooned with the Medal of Honor and rows upon rows of ribbons. A proud Master Parachutist and military skydiver, he showed them the polished jump boots he’d been working on, and asked Bennett to touch up the spit shine. Though his feet might not be visible in his coffin, he wanted that shine just right.

As they left, Col. Howard thanked Bennett, and then saluted him and held his hand crisply to his eyebrow until Bennett returned it. Bob Howard passed away two days before Christmas.

This great hero, a humble knight who was a paragon for all, belongs to history now. He is survived by his daughters Denicia, Melissa and Rosslyn; an Airborne-Ranger son, Robert Jr., and four grandchildren.

@SOLDIER OF FORTUNE MAGAZINE COPYRIGHT Use only with permissions and credits

The 264 Winchester Magnum is a 6.5mm cartridge that was ahead of its time when created in 1958. It slipped into a coma in the mid-1960s and has been at death’s door ever since.

But it could revive, perhaps even thrive because it produces better ballistics than all but one or two of the current crop of 6.5mms.

Given today’s mania over all things 6.5mm, the 264 Winchester Magnum should be a top performer in these long-reach hunting rifles everyone seems to covet. This belted magnum cartridge bests the 6.5 Creedmoor by about 400 fps.

That’s like stepping from a 308 Winchester to a 300 Winchester Magnum in performance improvement. If you want a 6.5mm with flat trajectory, maximum power, and minimum wind deflection, you want a closer look at the 264 Win. Mag.

Despite it’s 21st century ballistic performance, the 264 Win. Mag. is old. Many would say doddering. They’d be wrong. With today’s powders and bullets, it could finally realize its rich potential. Before that can happen, however, more shooters need to understand the cartridge.

And more ammunition manufacturers need to begin loading to reach that potential. Currently Winchester doesn’t even come close, limiting its 264 Win. Mag. to just one load, a 140-grain Power Point (B.C. .384) at 3,030 fps. Nosler does a much better job with a variety of great loads featuring bullets from 100-grains to 140-grains. Hornady has one load pushing a 140-grain InterLock with a B.C. of .465.

This is an adequate start, but a good handloader will get the most from the 264 Win. Mag. because, ballistically, anything the 6.5 Creedmoor can do, the 264 Winchester Magnum can blow out of the water.

The quickest route to appreciating the 264 Winchester Magnum is through the 7mm Remington Magnum. Both cartridges were formed from the belted 375 H&H Magnum case.

You can nit pick and say it was the 300 H&H Magnum case, but that was itself squeezed down from the 375 case. What matters is the head diameter, that belt around it, and the basic body diameter. You can easily reshape the length, neck diameter, shoulder angle, and taper of a case, but not its head diameter.

The belted .532-inch head of Holland & Holland’s 375 of 1912 is considerably wider than the .473-inch head of the 30-06 Springfield, which is what the 6.5 Creedmoor stands on. The 264 Win. Mag. case is .58-inch longer than the Creedmoor, too. It fits the same actions as the 270 Win. and 30-06. Bigger case, more powder… Boom. There you go.

Roy Weatherby mined this volume beginning with his 270 Wby. Mag. in 1943. Winchester came to the 375 belted magnum party in 1956 with the release of its 458 Win. Mag. They straightened the 375’s walls and cut its length to 2.5” for an easy fit into Model 70 magazines.

In 1958 they necked this big case down to create the 338 Win. Mag. and then necked it even smaller to make the 264 Win. Mag. Few hit the streets until 1959, but then…

Right away this “overbore” belted magnum created a stir. It came in a M70 Westerner rifle with a 26-inch barrel. Winchester advertised muzzle velocity at 3,200 fps with a 140-grain, .264” diameter bullet. SAAMI specifications for the cartridge allowed it a maximum pressure of 64,000 psi, same as the 300 Win. Mag. which came later.

With these numbers, the 264 Winchester Magnum was the immediate long-range, high-velocity, flat-trajectory answer to the western hunter’s prayers. And it came in affordable M70 rifles. The cartridge and rifle enjoyed immediate success and everyone was happy until…

Remington unleashed its 7mm Rem. Mag. It was 1962, the same year the first Wal-Mart opened, John Glenn first orbited the Earth, Marylin Monroe died, and Decca Records turned down the Beatles.

Nobody appeared to turn down the 7mm Rem. Mag. Here was the same belted magnum case, same length, and same shoulder slope as the 264 Winchester Magnum. Just a slightly wider neck, one that would hold a .284” bullet. Subtract .264 from .284 and you enjoy a mere .020” diameter advantage with 7mm Rem. Mag. bullets.

Doesn’t seem like much, but Remington wisely offered its new 7mm magnum with bullets as heavy as 175-grains. To hunters familiar with 150- to 180-grain bullets in 270 Winchesters and 30-06 Springfields, that sounded like serious elk, moose, and bear medicine. Winchester’s heaviest (140-grain) .264 bullet didn’t quite match up.

It probably didn’t help that Remington was chambering its new 7mm in its equally new M700 rifle advertised as “the world’s strongest” (three rings of steel surrounded the cartridge head.) If you didn’t mind a push-feed bolt action, the 7mm Rem. Mag. was an easy pick. Throw in the more convenient 24-inch barrel of the 7mm and it was no contest.

At about this same time so many bullets had already scorched the barrels of 264 Winchester Magnums that shooters began to notice early accuracy declines. Many were shooting the rifles fast and furiously at various rodents. After all, the 264 Win. Mag. could fire 85-grain hollow points 3,700 fps and 100-grain projectiles 3,600 fps.

With such light bullets, recoil wasn’t bad in an 8-pound rifle, just 15.4 f-p of free recoil energy compared to 20 f-p of punch with a 140-grain bullet. There’s nothing like blasting big doses of hot powder down a narrow bore in rapid succession to encourage throat erosion. The 264 Winchester Magnum got branded a barrel burner and was soon placed on life support.

But that was then and this is now. The incredible popularity of the 6.5 Creedmoor has inspired interest in any and all cartridges that spit a .264” bullet. Today we have the 26 Nosler and 6.5-300 Wby. Mag. Both of these burn much more powder in much larger cases than does the 264 Win. Mag. This gives them roughly a 100- to 150-fps muzzle velocity advantage over the 264 Win. Mag. But they also raise an important question…

If the 264 Winchester Magnum is a “barrel burner,” what should we call these larger cartridges? Barrel vaporizers?

While we are questioning speed, powder consumption, and barrel life, let’s address this issue with the 264 Winchester Magnum versus the 6.5 Creedmoor. One of the major selling points of the CM is its conservative consumption of powder and concomitant light touch on bores.

On average 6.5 CM barrels are supposed to maintain stellar accuracy through 2,000 to 3,000 shots, depending on the barrel steel and how “hot” the barrel was shot. In comparison some 308 Win. barrels have been reported to remain acceptably accurate for 5,000 shots, some 243 Winchesters just 2,000 shots, 25-06 Rems. 1,500 to 2,500 shots.

I’ve heard claims of 600 to 1,000 shots for the 26 Nosler, 1,000 to as many as 2,500 for 264 Win. Mags. This all varies depending on the barrel, whether it was cryo-treated, and how quickly subsequent shots are sent down the tube. The hotter you shoot them, the faster they deteriorate.

Obviously, shooters must ask themselves what they value most in a rifle. If you want to shoot 20 rounds in a minute and 200 rounds in a day, you don’t want a fire-breathing magnum.

If you want the flattest trajectory, least wind deflection, and most downrange energy for terminating bucks and bulls, you do want the larger powder capacity magnum. One to three shots at game every few weeks each fall aren’t going to destroy rifle accuracy until you’ve put a decade or more of hunting behind you.

By then you should have saved up enough $ for a replacement barrel. They make those by the thousands. Someone once compared throttling back bullet speed to driving your truck 20 mph so the tires would last longer.

Another consideration is how far you wish to target game and whether or not you use a laser rangefinder. Our ability to precisely measure distance-to-target contributes more to the success of long range shooting than the fastest magnum and highest B.C bullets.

What do we care if we dial an extra few MOA or select sub-reticle 6 instead of 4 to score on a long poke? Now, if you’re old school and like to hunt with MPBR, the flattest shooting magnum can make a big difference.

With a 6.5 Creedmoor sending a B.C. .529 bullet at 2,700 fps, you can aim dead center on a 10-inch target and hit it clear out to 334 yards. Send that same bullet 3,021 fps from a 264 Win. Mag. and you stay on target all the way to 372 yards.

By the way, all these 6.5mm cartridges shoot the same (.264”) bullets. The only differences among all them are powder capacity, head and body size, Cartridge Overall Length, and cost.

Go with the short ones if you find benefit in a short bolt throw and lighter, more compact rifle at lower cost per loaded box. Go with the long ones if you want maximum ballistic performance and hang the cost. Go small and short if you want long barrel life, big and long if you want – you guessed it — maximum ballistic performance.

Stated another way, when shopping for ballistic performance in a 6.5mm hunting cartridge, the main thing to compare are average muzzle velocities with any bullet weight.

Today’s fashion is to fling the longest projectile with the highest B.C.s, so let’s compare some MVs using a reasonably high B.C. Nosler Custom Competition 140-grain match bullet. There are some 2- to 7-grain heavier hunting bullets out there, but this is close enough for consistent comparisons.

We will take this opportunity to gently chide our bullet makers to raise the weight limit on high B.C. .264-caliber bullets so we can enjoy the long range possibilities with our higher velocity 6.5mms.

If they can stretch .284 (7mm) bullets to 180-grains, surely they can get .264s to 160-grains. In conformations like Berger VLD’s, Hornady ELDs or Nosler AccuBond LongRanges, B.C.s might approach an incredible .700.

But I’m a hunter, not a metallurgist/bullet maker. Perhaps they can’t draw jackets long enough for that. Longer bullets will require faster twist barrels. You might want to order your 264 Win. Mag. with a 1:8 or even 1:7 twist barrel. Sierra recently announced an exciting new 150-grain Hollow Point Boat Tail MatchKing.

It needs a 1:7.5 twist or faster. Matrix Ballistics recommends 1:8 twist for both its VLD 150-grain Match bullet and its 160-grain hunting bullet. Wait a minute! 160-grain? They can build one! And it’s rated B.C. .685. That would be one to try on a 264 Win. Mag. Serious elk, moose, kudu hammer.

Do be aware that some magnum 6.5 shooters are reporting extreme copper fouling with some bullets. They’re also seeing disintegration of light, thin-jacketed bullets at extreme velocities. When you start playing the extreme velocity game, you can find yourself skating thin ice.

For comparison purposes, here are some popular 6.5 cartridges showing muzzle velocities with 140-grain bullet (B.C. 529) taken from Nosler Reloading Guide 7. Barrel lengths vary. All zeroed at 250 yards. 500-yard ballistic performance data includes 10 mph right-angle wind.

Other Reloading Guides may list different top end velocities. Recoil energies are calculated in an 8-pound rifle. Shooters should realize that these top MVs can vary as much as 100 fps from barrel to barrel, rifle to rifle, but this should provide a good basis for comparison.

Cartridge M.V. 500-yd drop “ /Drift “ /Energy fp. Free Recoil Energy/fp

6.5 Creedmoor 2730 -38/16.2/1252 12.34 fp

6.5×55 Swede 2790 -36/15.7/1316 14.19 fp

260 Rem. 2830 -35.2/15.3/1359 13.24 fp

6.5-06 2906 -33/14.7/1444 14.59 fp

6.5-284 Norma 2953 -32/14.4/1497 15.30 fp

6.5 PRC 960 -31.8/14.4/1505 16.96 fp

264 Win. Mag. 3021 -30/14/1576 16.95 fp

6.5 Rem. Mag. 3059 -29.6/13.7/1621 17.37 fp

26 Nosler 3300 -25/12.3/1918 26.25 fp

6.5-300 Wby. Mag. 3395 -23.5/11.9/2041 26.40 fp

As always, burning ever more powder behind a given diameter bullet increases costs in ammo, recoil, noise, and barrel life. But it also maximizes ballistic performance.

It’s up to each individual shooter to determine what works for him or her. From where I sit, the old 264 Win. Mag. is starting to look like a pretty reasonable, middle-of-the-road cartridge in the 6.5mm cartridge line up.

If you’re not fixated on extreme barrel life, short-action rifles or joining the 6.5 Creedmoor flock, the under-appreciated 264 Win. Mag. might be your baby. Just don’t expect to find rifles or ammo on every corner or at discount prices. Check premium brands and semi-custom rifles like Fierce, Bergara, Rifles, Inc., Cooper, Hill Country Rifles, Bansner, etc.

The 264 Winchester Magnum is a cartridge for serious riflemen/women who appreciate its power and reach in the pursuit of big game.

I wouldn’t call it a good option for plinking or high-volume target shooting. If I found a used rifle in good condition at a good price and it was chambered 264 Win. Mag., I’d probably buy it, especially if it was a pre-64 Winchester M70. (You can read about another great 6.5mm option, the 6.5-284 Norma, in this article. )

Much as author Ron Spomer admires the 6.5mm cartridges, he’s used them the least for his hunting. He hopes to change that over the next few seasons.