Now sadly I have come to the conclusion after reading this article below. Is that it is steel on target on.

Since it seems to me that if we had a Eisenhower, Patton, Smedley Butler or a Chesty Puller in charge of our troops over in the Sandbox.

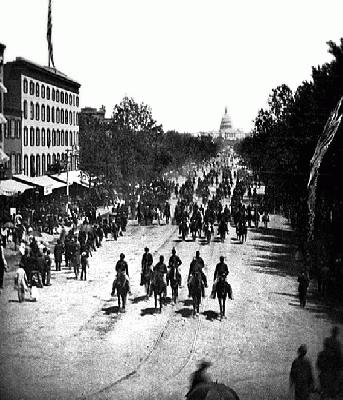

Then we would have of had a Victory Parade down Pennsylvania Ave with the troops several years ago.

I just hope that a lot more high powered folks than I. Have read this article below.

YOUR FAVORITE ARMY GENERAL ACTUALLY SUCKS

THE U.S. ARMY only seems impressive. Yes, it’s got plenty of tactically competent and physically heroic enlisted soldiers and low-ranking officers. But its generals are, on the whole, crappy, according to a new book that’s sure to spark teeth-gnashing within the Army.

That book is The Generals, the third book about the post-9/11 military by Tom Ricks, a fellow at the Center for a New American Security and the *Washington Post’*s former chief military correspondent. Scheduled to be released on Tuesday, The Generals is a surprisingly scathing historical look into the unmaking of American generalship over six decades, culminating in what Ricks perceives as catastrophic failures in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The basic problem is that no one gets fired. Ricks points back to a system that the revered General George Marshall put into place during World War II: unsuccessful officers – defined very, very liberally – were rapidly sacked, especially on the front lines of Europe. Just as importantly, though, getting relieved of command didn’t end a general’s career. Brig. Gen. “Hanging Sam” Williams, was removed as the assistant commander of the 90th Infantry Division in western France in 1944 for lacking “optimism and a calming nature” in the view of his superior. Six years later, Williams commanded the 25th Infantry Division in Korea and retired as a three-star. Marshall’s approach simultaneously held generals accountable for battlefield failures while avoiding a zero-defect culture that stifled experimentation.

Over the course of six decades, Ricks demonstrates at length, the Army abandoned Marshall’s system. It led to a culture of generalship where generals protected the Army from humiliation – including, in an infamous case, Maj. Gen. Samuel Koster covering up the massacre of civilians at My Lai – more than they focused on winning wars. On the eve of Vietnam, “becoming a general was now akin to winning a tenured professorship,” Ricks writes, “liable to be removed not for professional failure but only for embarrassing one’s institution with moral lapses.”

It’s not an airtight case. Ricks is sometimes at pains to explain why good generals who probably should have been fired under Marshall weren’t (George Patton) or why adaptive generals later on weren’t driven out of the Army (David Petraeus). And it’s overstated to blame dumb wars on dumb generals. But the fact is, the Army almost never fires generals for cause, unlike the Navy, to the point where a lieutenant colonel famously wrote in frustration during the Iraq war that a private who loses a rifle is more likely to be disciplined than a general who loses a war.

Ricks explains how it got to be that way. And it’s something the Army has to reckon with as it deals with its future now that its decade of perpetual warfare is ending, and ending inconclusively. He spoke with Danger Room right before The Generals dropped its bomb on the Army.

Danger Room: So how poor are today’s Army generals? What percentage of them would you say need to be fired outright? Is the public wrong for seeing the Army as an uber-competent institution, a learning organization and a meritocracy?

Tom Ricks: The U.S. Army is a great institution – tactically. Our soldiers today are well-trained, well-motivated, cohesive, and fairly well equipped.

But training is for the known. For the unknown, education is required. You need to teach your senior leaders how to address problems full of uncertainty and ambiguity, and from them, fashion a strategy. And then be able to tell whether it is working, and to adjust if it isn’t.

Our generals today are not particularly well-educated in strategy. Exhibit A is Tommy Franks, who thought it was a good idea to push Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda from Afghanistan into Pakistan, a larger country that also possesses nuclear weapons. Franks also thought that he had won when he took the enemy’s capital in Afghanistan and Iraq — when in fact that is when the wars really began.

When generals don’t know what to do strategically, they tend to regress back down to what they know, which is tactical. That’s one reason why in Vietnam you saw colonels and generals hovering over company commanders giving orders. It is also why our generals were so slow to adapt in Iraq. By the time they became operationally effective, it was 2007, and we had been fighting in Iraq for nearly four years, longer than we had during all of World War II.

What percentage of them need to be fired? All those who fail. That is how George Marshall ran the Army during World War II. Failures were sacked, which is why no one knows nowadays who Lloyd Fredendall was. Successful generals were promoted – which is why why we know names of younger officers of the time such as Eisenhower, Ridgway and Gavin. This was a tough-minded, Darwinian system that reinforced success. Mediocre wasn’t enough back then. It is now, apparently. Back in World War II, a certain percentage of generals were expected to be fired. It was seen as a sign that the system was working as expected.

DR: How would George Marshall’s system of relieving failing generals and placing them in remedial positions work today? Wouldn’t a relief inevitably be seen as an irredeemable black mark?

TR: Relief today is indeed a black mark. The system only works if relief is so frequent that it isn’t seen as a career-ender. Of the 155 men who commanded Army divisions in combat during World War II, 16 were fired. Of those, five were given other divisions to command in combat later in the war. Many others who were fired got good staff jobs, or trained divisions back home.

That said, Marshall was pretty hardnosed about this. He didn’t run the Army for the benefit of its officers. In a war for democracy, he wrote, the needs of the enlisted came first. He believed that the Army owed its soldiers competent leadership. That was not the case with the Army in Vietnam, where officers were rotated in quickly to get some time in combat command and then rotated out.

DR: Isn’t it too simplistic to blame bad generalship for lost wars and good generalship for successful ones? Tommy Franks may have been “dull and arrogant,” as you write, but he didn’t decide to invade Iraq; David Petraeus may have been his polar opposite, but Afghanistan is in shambles.

TR: Yes, it would be too simplistic. That’s why the major second theme of the book is the need for good discourse between our top generals and their civilian overseers.

By good discourse, I don’t mean everyone getting along. I mean dialogue that welcomes candor, honesty, and clarity, and is guided so it does two key things: explore assumptions and dig into differences. For example, the Vietnam War was guided on the assumption that the enemy had a breaking point and that it would come before ours. Turns out that was wrong. Likewise, the 1991 Gulf War was run on the assumption that giving Saddam Hussein a good thumping would remove him from power. Didn’t happen.

I came away from the book thinking that the quality of civil-military discourse is one of the few leading indicators you have of how well a war will go. George Marshall was not the natural choice for Army chief of staff (Hugh Drum probably was) but FDR picked him in part because Marshall twice had stood up to Roosevelt in the Oval Office, respectfully but forcefully dissenting on key military issues.

DR: Isn’t relieving generals when they’re generals too late? Why shouldn’t the relieves and reassignments you describe in the book come earlier in their tenures as officers? Or can you really teach a general new tricks?

TR: Yes. And yes – if generals see that getting promoted requires some prudent risk-taking, some adaptation, they will do so and learn those tricks. But they won’t if they see that cautious mediocrity is rewarded equally.

DR: Can you make up your mind about Gen. Ray Odierno already? He was a villain in your first book about the Iraq war, a hero in your second, and now he’s a villain again, for giving one of his subordinate commanders a slap on the wrist for obstructing an inquiry into his soldiers’ abuse of Iraqis. Is Odierno fit to serve as Army chief of staff?

DR: I am of two minds about Gen. Odierno. I do think he screwed up when he commanded the 4th Infantry Division early in the Iraq war. But the bottom line is he adapted. You got to learn to live with a little ambiguity, Spencer!

DR: You write that “It seems a good bet that there will not be a ‘Petraeus generation’ of generals.” I took that to mean a more competent and far-sighted general officer corps, but you might also have meant one steeped in counterinsurgency. If you mean the former, why shouldn’t we expect one, since Petraeus remains a remarkably influential figure in the Army even to soldiers who never served under him? If you mean the latter, why is that something to lament? There’s an argument to be made that one of the reasons Afghanistan remains a mess is because the Army and Marines drank the counterinsurgency Kool-Aid too deeply.

TR: Nah, I mean competent, adaptive generals. But one aspect of being adaptive is being able to think critically. I think COIN worked for Petraeus during the surge, but it was a very tough-minded, violent COIN strategy. And it involved risk-taking – like Petraeus striking a private ceasefire with the Sunni insurgents and putting 100,000 of them on the American payroll, and doing it all without asking permission from President Bush.

An aside on COIN: It was in fashion a few years ago. It is out of fashion now. But we shouldn’t fight our wars based on what the cool kids think. We should use what works, and be willing to try other things if what we try doesn’t work. That’s my gripe with Petraeus’ predecessor in Iraq, George Casey [who later became Army chief of staff].

THE U.S. ARMY only seems impressive. Yes, it’s got plenty of tactically competent and physically heroic enlisted soldiers and low-ranking officers. But its generals are, on the whole, crappy, according to a new book that’s sure to spark teeth-gnashing within the Army.

That book is The Generals, the third book about the post-9/11 military by Tom Ricks, a fellow at the Center for a New American Security and the *Washington Post’*s former chief military correspondent. Scheduled to be released on Tuesday, The Generals is a surprisingly scathing historical look into the unmaking of American generalship over six decades, culminating in what Ricks perceives as catastrophic failures in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The basic problem is that no one gets fired. Ricks points back to a system that the revered General George Marshall put into place during World War II: unsuccessful officers – defined very, very liberally – were rapidly sacked, especially on the front lines of Europe. Just as importantly, though, getting relieved of command didn’t end a general’s career. Brig. Gen. “Hanging Sam” Williams, was removed as the assistant commander of the 90th Infantry Division in western France in 1944 for lacking “optimism and a calming nature” in the view of his superior. Six years later, Williams commanded the 25th Infantry Division in Korea and retired as a three-star. Marshall’s approach simultaneously held generals accountable for battlefield failures while avoiding a zero-defect culture that stifled experimentation.

Over the course of six decades, Ricks demonstrates at length, the Army abandoned Marshall’s system. It led to a culture of generalship where generals protected the Army from humiliation – including, in an infamous case, Maj. Gen. Samuel Koster covering up the massacre of civilians at My Lai – more than they focused on winning wars. On the eve of Vietnam, “becoming a general was now akin to winning a tenured professorship,” Ricks writes, “liable to be removed not for professional failure but only for embarrassing one’s institution with moral lapses.”

It’s not an airtight case. Ricks is sometimes at pains to explain why good generals who probably should have been fired under Marshall weren’t (George Patton) or why adaptive generals later on weren’t driven out of the Army (David Petraeus). And it’s overstated to blame dumb wars on dumb generals. But the fact is, the Army almost never fires generals for cause, unlike the Navy, to the point where a lieutenant colonel famously wrote in frustration during the Iraq war that a private who loses a rifle is more likely to be disciplined than a general who loses a war.

Ricks explains how it got to be that way. And it’s something the Army has to reckon with as it deals with its future now that its decade of perpetual warfare is ending, and ending inconclusively. He spoke with Danger Room right before The Generals dropped its bomb on the Army.

Danger Room: So how poor are today’s Army generals? What percentage of them would you say need to be fired outright? Is the public wrong for seeing the Army as an uber-competent institution, a learning organization and a meritocracy?

Tom Ricks: The U.S. Army is a great institution – tactically. Our soldiers today are well-trained, well-motivated, cohesive, and fairly well equipped.

But training is for the known. For the unknown, education is required. You need to teach your senior leaders how to address problems full of uncertainty and ambiguity, and from them, fashion a strategy. And then be able to tell whether it is working, and to adjust if it isn’t.

Our generals today are not particularly well-educated in strategy. Exhibit A is Tommy Franks, who thought it was a good idea to push Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda from Afghanistan into Pakistan, a larger country that also possesses nuclear weapons. Franks also thought that he had won when he took the enemy’s capital in Afghanistan and Iraq — when in fact that is when the wars really began.

When generals don’t know what to do strategically, they tend to regress back down to what they know, which is tactical. That’s one reason why in Vietnam you saw colonels and generals hovering over company commanders giving orders. It is also why our generals were so slow to adapt in Iraq. By the time they became operationally effective, it was 2007, and we had been fighting in Iraq for nearly four years, longer than we had during all of World War II.

What percentage of them need to be fired? All those who fail. That is how George Marshall ran the Army during World War II. Failures were sacked, which is why no one knows nowadays who Lloyd Fredendall was. Successful generals were promoted – which is why why we know names of younger officers of the time such as Eisenhower, Ridgway and Gavin. This was a tough-minded, Darwinian system that reinforced success. Mediocre wasn’t enough back then. It is now, apparently. Back in World War II, a certain percentage of generals were expected to be fired. It was seen as a sign that the system was working as expected.

DR: How would George Marshall’s system of relieving failing generals and placing them in remedial positions work today? Wouldn’t a relief inevitably be seen as an irredeemable black mark?

TR: Relief today is indeed a black mark. The system only works if relief is so frequent that it isn’t seen as a career-ender. Of the 155 men who commanded Army divisions in combat during World War II, 16 were fired. Of those, five were given other divisions to command in combat later in the war. Many others who were fired got good staff jobs, or trained divisions back home.

That said, Marshall was pretty hardnosed about this. He didn’t run the Army for the benefit of its officers. In a war for democracy, he wrote, the needs of the enlisted came first. He believed that the Army owed its soldiers competent leadership. That was not the case with the Army in Vietnam, where officers were rotated in quickly to get some time in combat command and then rotated out.

DR: Isn’t it too simplistic to blame bad generalship for lost wars and good generalship for successful ones? Tommy Franks may have been “dull and arrogant,” as you write, but he didn’t decide to invade Iraq; David Petraeus may have been his polar opposite, but Afghanistan is in shambles.

TR: Yes, it would be too simplistic. That’s why the major second theme of the book is the need for good discourse between our top generals and their civilian overseers.

By good discourse, I don’t mean everyone getting along. I mean dialogue that welcomes candor, honesty, and clarity, and is guided so it does two key things: explore assumptions and dig into differences. For example, the Vietnam War was guided on the assumption that the enemy had a breaking point and that it would come before ours. Turns out that was wrong. Likewise, the 1991 Gulf War was run on the assumption that giving Saddam Hussein a good thumping would remove him from power. Didn’t happen.

I came away from the book thinking that the quality of civil-military discourse is one of the few leading indicators you have of how well a war will go. George Marshall was not the natural choice for Army chief of staff (Hugh Drum probably was) but FDR picked him in part because Marshall twice had stood up to Roosevelt in the Oval Office, respectfully but forcefully dissenting on key military issues.

DR: Isn’t relieving generals when they’re generals too late? Why shouldn’t the relieves and reassignments you describe in the book come earlier in their tenures as officers? Or can you really teach a general new tricks?

TR: Yes. And yes – if generals see that getting promoted requires some prudent risk-taking, some adaptation, they will do so and learn those tricks. But they won’t if they see that cautious mediocrity is rewarded equally.

DR: Can you make up your mind about Gen. Ray Odierno already? He was a villain in your first book about the Iraq war, a hero in your second, and now he’s a villain again, for giving one of his subordinate commanders a slap on the wrist for obstructing an inquiry into his soldiers’ abuse of Iraqis. Is Odierno fit to serve as Army chief of staff?

DR: I am of two minds about Gen. Odierno. I do think he screwed up when he commanded the 4th Infantry Division early in the Iraq war. But the bottom line is he adapted. You got to learn to live with a little ambiguity, Spencer!

DR: You write that “It seems a good bet that there will not be a ‘Petraeus generation’ of generals.” I took that to mean a more competent and far-sighted general officer corps, but you might also have meant one steeped in counterinsurgency. If you mean the former, why shouldn’t we expect one, since Petraeus remains a remarkably influential figure in the Army even to soldiers who never served under him? If you mean the latter, why is that something to lament? There’s an argument to be made that one of the reasons Afghanistan remains a mess is because the Army and Marines drank the counterinsurgency Kool-Aid too deeply.

TR: Nah, I mean competent, adaptive generals. But one aspect of being adaptive is being able to think critically. I think COIN worked for Petraeus during the surge, but it was a very tough-minded, violent COIN strategy. And it involved risk-taking – like Petraeus striking a private ceasefire with the Sunni insurgents and putting 100,000 of them on the American payroll, an