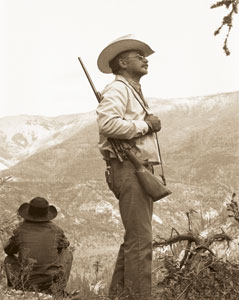

When I was a lot younger and thinner. I always look forward to the newest issue of Shooting Times. Especially when Skeeter writing was in it.

Now it can be safely said that this guy really lived out his time on this planet!

Here is a brief outline of his life & career.

Skeeter Skelton

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Charles Allan ‘Skeeter’ Skelton (May 1, 1928 – January 17, 1988) was an American lawman and firearms writer. After serving in the US Marine Corps from 1945-46 he began a law enforcement career which included service with the US Border Patrol, a term as Sheriff of Deaf Smith County, Texas, and investigator with both the US Customs Service and Drug Enforcement Administration. After his first nationally published article hit newsstands in September 1959, Skelton began writing part-time for firearms periodicals. In 1974 he retired from the DEA and concentrated full-time on his writing.[1]

Contents

[hide]

Writing[edit]

Skelton wrote his first article for Shooting Times in 1966, in 1967 he became the handgun editor for the magazine until his death in 1988. His periodical articles were collected in Good Friends, Good Guns, Good Whiskey: Selected Works of Skeeter Skelton and Hoglegs, Hipshots and Jalapeños : Selected Works of Skeeter Skelton.[2][3] He was a contemporary of Bill Jordan, Charles Askins and Elmer Keith.

Skelton’s work frequently poked fun at himself. His “Me and Joe” stories of his Depression-era youth, while including references to period firearms, were character-oriented rather than technical pieces. His ‘Dobe Grant’ and ‘Jug Johnson’ short stories were perhaps the only fiction routinely published by a popular shooting magazine. His son Bart Skelton is a gun writer.

Shooting Times magazine is currently reprinting past “Hip Shots” articles by Skelton.

Legacy[edit]

Skelton is credited by firearms writer John Taffin with the revival of the .44 Special round.

References

- Jump up^ Taffin, John (2005). Single Action Sixguns. Krause Publications. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-87349-953-8.

- Jump up^ Skelton, Skeeter (1988). Good Friends, Good Guns, Good Whiskey: Selected Works of Skeeter Skelton. = PJS Publications. ISBN 978-0-9621148-0-9.

- Jump up^ Skelton, Skeeter (1991). Hoglegs, Hipshots and Jalapeños : Selected Works of Skeeter Skelton. = PJS Publications. ISBN 978-0-9621148-6-1.

- Jump up^ Taffin, John (2006). Gun Digest Book of the .44. Gun Digest Books. pp. 65, 72. ISBN 978-0-89689-416-7.

____________________________________ ____________________________________

____________________________________

.

I just wish that I could write 1/10 as will as he could. He also wrote a couple of really good books about his love of guns

So I copied this from The Dark Canyon Web site. Enjoy!

They Were Good, But . . .

by Skeeter Skelton

Shooting Times Magazine

May 1969

Epitaph For 3 Cartridges

The words said by his cohorts at the wake of a departed comrade can come nearer to describing him than the eulogy of the most golden-throated and well meaning of pastors, who maybe only met him on those rare Sundays it was too bad out to go hunting. And though some of us frostier-topped types don’t want to face it, the time has come to lay away not one, but three old pards.

This hadn’t dawned on me until one of the infrequent inventories of my mess of gear turned up a few mixed, partially full boxes of handgun ammunition in calibers 44-40, 38-40, and 32-20. The labels and generally scruffy condition of the cartons showed clearly that they had been around a lot longer than the glossier, styrofoam-inserted boxes that sided them. How long had it been since I owned a sixgun for these relics of a better, slower-paced time?

It was easy to remember that first handgun because it had come rather hard, costing the best part of a summer’s wages. Twelve-year-olds didn’t draw top money when I was young, and the 38WCF Colt single action and that first box of shells required an in-ordinate amount of flunkying about the farm.

I had been touted onto the 38-40 as the best handgun caliber going by an ex-Texas Ranger. “These automatics they carry nowdays – they’s nothin’ to ’em, nothin’ to ’em at all,” he counseled. “The Colt 45 is a good ‘un, and the 44 too. But if you want a gun that shoots hard, get you a 38-40. Don’t kick as much, neither.”

When this old cactus jumper held forth on these three calibers he meant them to be in only one gun, the single action Colt. If he was aware of the existence of other revolvers for the loads, he dismissed them from his mind as trifles.

And there were others. Certainly the best known and most frequently encountered, the Colt Model P single action in 44-40, 38-40, and 32-20 was a quick addition to the original 44 Rimfire, 44 Colt, and 45 Colt guns. The alacrity with which the Hartford company introduced the newer, and not necessarily superior, cartridges into their revolvers was prompted by the immense popularity of the 1873 Winchester rifle in those calibers.

When the Winchester ’73 first came in use it was doubtlessly a good idea to have a handgun that used the same ammunition. The little 44 rifle, however, is held by some as having been employed in the place of a handgun by many of its devotees, simply because it made use of their greater ability to hit with a rifle.

It also makes sense that if both a sixgun and a rifle were to be carried the rifle would be much more useful if it fired one of the more powerful cartridges of the day.

While the firepower of the ’73 made it a more versatile companion gun to the Colt than, say, the single shot 45-70 Springfield or 50-100-500 Sharps, it certainly was outclassed for the purpose by the 1876 and the later 1886 Winchesters which threw heavy buck busters like the 45-70, 45-90, 40-82, et al.

The ’92 Winchester was simply a scaled-down 1886, made for riflemen who wanted a fast shooting turkey gun. By the 90s, most serious riflemen had turned to longer ranged guns for hunting and defense, and the 44-40, 38-40, and 32-20 were used on the big stuff only by those who were too poor or too ignorant of ballistics to choose a better rifle.

The Texas Rangers were the last of the old time horseback policemen, and frequently rode far from supply sources. The worth of this combination rifle and revolver cartridge can be surmised in old photographs of ranger groups, which show that they stayed abreast of things and armed themselves with 1894 30-30 and 1895 30-40 Winchesters almost as soon as they were introduced.

Frank Hamer, the great ranger captain who rid society of Bonnie and Clyde, started his service as a very young man of 21 in 1906. Early photos show him with a ’94 Winchester. He soon switched to a Model 8 Remington automatic in 25 Remington, and was armed with the same type rifle in 35 Remington during his famous fight with the vicious pair.

Especially during the late 1870’s and early 1880’s, there must have been riders who carried revolver and rifle combinations in these calibers. More, I expect , in 44-40 and 38-40 than in the rather tiny 32-20. But mostly the users of the Winchester, Marlin, Colt, and other shoulder guns in these calibers employed these light rifles in lieu of a handgun. Handgunners stayed with these cartridges and the many revolvers made for them over the years because they were excellent handgun cartridges for the times.

The little Winchester rounds were chambered into a goodly assortment of handguns other than old Sam’s thumbuster. In fact, Winchester made up a few single action revolvers in 44-40 which boasted one of the first swing-out cylinders. It has been said that this was done to have some bargaining power for forcing Colt from the rifle business and that a deal was made whereby Winchester made rifles and shotguns and Colt made only handguns for a long time thereafter.

After the Model P was enjoying good health, Colt in 1877 introduced the Double Action Army. These oddly shaped sixguns were on 45 frames and were originally in that calibration, with 44-40, 41 Long Colt, 38-40, and 32-20 models coming later.

A total of slightly more than 50,000 of the side-ejection double actions, in all calibers combined, were made. Their somewhat fragile locking systems and perhaps their ugly sawhandle grips contributed to their comparatively early demise.

The next Colt made for the Winchesters shells is acclaimed by some as the most rugged revolver ever made. The New Service was manufactured from 1898 until 1941, with a few wartime guns being put together as late as 1943. During this span, the big DA sixgun was offered in a great many calibers, including various British service cartridges such as the 450, 455, and 476 Eley group, but the first variants from its initial 45 Colt boring were the 44-40 and 38-40. Unlike earlier heavy frame Colts, the New Service was never produced in 32-20.

This is not to say that there were no Colt double actions in 32-20. The Army Special, a 41-framed DA revolver was produced from 1908 until 1928, when it became the Official Police. Although best known in 38 Special, these fairly heavy guns made particularly nice small game getters when chambered for the 32 WCF. Another, lighter Colt in this caliber was the Police Positive Special, found in 32-20 with 4″, 5″, and 6″ barrels, and occasionally in a target model with adjustable sights.

The best known Smith & Wesson chambered for a Winchester rifle load is the venerable Military & Police model. Like Colt, S&W did not revive this caliber after WWII, but it remains a sought-after one in many areas, and I have seen a number of Smith 32-20 sixguns in use in Mexico. The light recoil of the factory ammunition makes it a comfortable gun to shoot, yet it is more powerful than other 32’s.

About 275 of the topbreak double action revolvers were produced in 38-40 by Smith & Wesson, along with an estimated 15,000 in 44-40. These guns were made between 1886 and 1910, but it came to be generally accepted that these loads were too powerful for topbreak revolvers. Also, about 2000 of the New Model 44 Russian caliber single action Smiths were made up for the 44-40 cartridge.

The beautiful New Century (Triple Lock) double actions by S&W are best known in 44 S&W Special, but a few were made in 45 Colt and 44-40. A successor to the New Century, the Hand Ejector was likewise predominantly a 44 Special, but a number were furnished in 44-40, including a model with adjustable sights.

The 1926 Hand Ejector Model, another fine Smith & Wesson designed around the 44 Special round, was made on special order for the 44 WCF. Many of these special order guns went to Central and South America, where the 44-40 enjoyed great popularity due, at least in part, to the numbers of Winchester ’73 and ’92 rifles (along with their Spanish Tigre copies) in use there.

Merwin & Hulbert marketed their versions of the Winchester-chambered revolvers, actually manufactured by Hopkins & Allen. Although quite sturdy, and still sometimes found in use in remote areas, these guns were never widely distributed after one of the partners was captured and killed by Indians.

The Winchester trio were the magnum handgun cartridges of their day. Jeff Milton, the illustrious peace officer who began his long career as a teenage Texas Ranger in 1880, told of swapping his 45 Colt single action for the first 44-40 SA he ever saw. His plans for being a 19th century swinger, with saddle carbine and sixshooter using the same shells, came to an abrupt halt when his new 44 froze up after the first shot. The primer had flowed back into the firing pin hole in the recoil shield. After struggling with both hands to shear off the protruding primer and recock the gun, Milton re-swapped for another 45 and warned his companions-at-arms against the new innovation. Even in those days a closely-brushed firing pin was a necessity when shooting hot loads.

It seems likely that the 38-40, at least from about 1890 on, was a more popular sixgun caliber among western lawmen than the 44-40. I have known many of the old officers of that period who favored the gun and load, and when pressed for a reason they would like my old ranger mentor, point our that the 38-40 “shot hard” and didn’t kick as much as the 45 or 44-40. This lack of recoil was due to the 38-40 being a heavier revolver shooting a lighter bullet than its two compatriots. Its 180 gr. flatnosed slug traveled almost 1000 fps, as did the similarly shaped 200 gr. bullet of the 44-40 – a respectable load even by today’s standards.

After black powder had fallen into disuse, the ammunition companies loaded high velocity ammo with smokeless powder cartridges for use in rifles only. This stuff was marked on the boxes, and should never be fired in revolvers. Ammunition compounded with the older sixguns in mind was marked as suitable for use in either rifles or revolvers in good condition.

As the years went by, this dual purpose ammo was loaded lighter until it falls far below the velocity potential of good rifles such as the ’92 Winchester and is considerably underpowered for a late, sound revolver.

When I was younger I handloaded for all three of the Winchester calibers. I did this because these were the guns that were available to me, and all the while I was hoping to acquire newer sixguns in 357 Magnum and 44 Special. Reloading this trio, especially the 44-40 and 38-40, was for the birds.

These two shells are heavily tapered over their powder chambers, then extend more or less straight to the mouth over the section of case which holds the bullet. Especially in the older, folded head cases, they stretch enormously, requiring excessive resizing and frequent trimming. Case life is short. While I prefer for general use the standard, original bullets, such as reproduced in the Lyman #40143 (38-40) and #42798 (44-40) molds, there are better cast slugs for reloading these two cartridges.

Lyman’s #401452 and #40188 are great in the 38-40, both being of semi-wadcutter design and both having crimping grooves. Several of the similarly-shaped 44 Special bullets work fine in the 44-40 when seated over appropriate powder charges, deep enough in the case to fall within maximum overall cartridge length requirements. These crimping grooves are most helpful, since the round-shouldered standard bullets are prone to being pushed back into the case during rough handling.

The 32-20 is not as susceptible to these failings, since its case has a straighter taper, but it still lacks the versatility and ease of reloading enjoyed by the modern, straight-cased shells. The new Ruger 30 Carbine revolver supplants the 32-20 completely, the 38 Special can be loaded to equal or better it, and there is no solid ground on which to compare it with the 357.

Anything the 38-40 could accomplish is done better with the 41 S&W Magnum, and who would pit the 44-40 against the 44 Magnum?

Tough old Judge Roy Bean was a realist who sold warm beer in a saloon named after the most beautiful woman of his time, Lily Langtry. In his time, these were the best. Confronted with the refrigeration and Sophia Loren, the judge would never look back.

And if he were here today, he’d say “Vayan con Diós” to the three little Winchester shells.

Here is another one

The .44 Special – A Reappraisal

by Charles A. Skelton

Shooting Times Magazine

August 1966

Note: This was one of Skeeters early articles for Shooting Times and he had not starting using his nickname of “Skeeter” in his byline.

In the uncomplicated days before the Great Misunderstanding of December 7, 1941, no one I knew had a .44 Special because no one I new could afford to by a gun. Although plenty of Smith & Wesson’s New Century (Triplelock), 1917 Hand Ejector, and 1926 Military models must have been around somewhere, I couldn’t find ’em.

Handgunnery in my Dust Bowl social circle was carried on with creaky old Colt single actions and modestly priced Iver Johnson Owlheads in .32 caliber . Forward-thinking pistoleros, a lot of them Texas Rangers, favored 1911 Colt .45 autos – mostly marked “United States Property,” relics of the Argonne Forest or some such.

Colt catalogs of the period mentioned that New Service, New Service Target, and Single Action Army models were in the .44 Special dimension, but the only ones I ever located reposed in the displays of affluent postwar collectors.

It was a situation to drive a man to the jug, and the inflated prices of a gunless, wartime market did nothing to help. Every year or two, if you were lucky, you might glimpse a classified ad offering a .44 Special revolver, at prices that would bankrupt a bricklayer. The postwar boom helped little. Years went by before any gunmaker got around to dishing up a good forty-four.

Through this whole mess, my appetites were honed by a dedicated group of individualists who called themselves “The .44 Associates.” At the time I thought these aficionados of the .44 Special rather smug. They already had their guns, and interchanged loading information and jokes about .357 shooters in a regular newsletter. My simmering envy of the .44 Associates was finally boiled over by the excellent magazine articles of Gordon Boser and the flamboyant Elmer Keith.

I sold my .38 Special. I sold my saddle. I cashed in my War Bonds and quit smoking. With bulging pockets, I walked to Polley’s Gunshop in Amarillo and paid my friend, Tex Crossett, $125 for a clean, tight .38-40 Colt single action. This was in the late ‘forties, and the thumbusters’ prices were still held high by the Colt factory’s refusal to tool up and produce them for their postwar fans.

Trying not to think of my stripped bank account, I shipped the old Colt to Christy Gun Works, who installed a matched .44 Special barrel and cylinder of their own manufacture. California’s old King Gunsight Company added a lowslung adjustable rear sight and a mirrored, beaded, ramp front. Somebody else did me a trigger job, and bright blued the whole package. Panting for breath, I plunked down 20 bucks for a pair of one-piece ivory grips, $20 more for bullet molds, sizers, and loading dies, and started a charge account to get empty cases. It had taken ten years, but I had my .44 Special.

Any handgunner who got his start less than ten years ago may well wonder what all the fretting was about. The .44 Magnum completes its first decade this year. A longer, stronger version of the .44 Special, it eclipses the performance of the Special even more than that cartridge overshadowed its own father, the .44 Russian. All fire bullets of the same diameter, of approximately the same weight, and revolvers of the newer calibrations will efficiently handle the older factory loadings.

The .44 S. & W. Special is simply a longer version of the .44 Russian, throwing the same bullet at the same velocity. It is inherently more accurate than any other pistol cartridge that I have fired, as loaded by the ammunition factories. This trait can be improved upon by handloading. Therein lies its fascination.

As a defense or hunting load, the factory .44 Special is on a par with the .45 ACP and the .38 Special – both notoriously poor performers. Commercial cartridges in .45 Colt, .44-40, .38-40, and .357 Magnum far outshine the leisurely moving, roundnosed .44, which for generations has maintained its staid, 760 fps pace. But put a bullet of the right configuration over a .44 Special case, crackling with enough of the right, slow burning powder, and its superiority to any of the above-named killers is so apparent as to make comparison a waste of time.

The .357 Magnum, with much justification, has enjoyed a heyday since 1935. Smith & Wesson’s advertising for this revolver used to proclaim, “The S & W ‘.357’ Magnum Has Far Greater Shock Power Than Any .38, .44, or .45 Ever Tested.” With factory loads, this was true. Handloaded, the .44 Special made the .357 – also handloaded to peak performance – eat dust. It was the case of a good big man beating hell out of a good little man.

Basic mathematics made it obvious to experimenters that if the .44 Special were loaded up to its maximum velocity – generally accepted as 1,200 fps at the muzzle with 250-grain bullets – it could skunk the 158-grain .357 slug at 1,500 fps.

Topped with cast bullets in Hollow-point form, both the .357 and .44 Special handloads ran several times higher than their closest competitors on General Julian Hatcher’s scale of relative stopping power. Significantly, the .44 had almost double the stopping effect of the .357 when this scale was applied, in spite of its moving at 300 less velocity.

Homebrewed work loads for my .44 were originally based on the excellent Lyman 429244 cast bullet, in both solid and hollowpoint form. For me, this was a natural choice of bullets after having found the .357 version of the same design – 358156 – to be an extremely accurate one in my guns of that caliber, and to shoot at maximum velocities without leading.

My gorgeous custom Colt ate up many hundreds of heavy loads with this bullet before I realized that the gascheck, so necessary to prevent leading in hot .357 loads, served no good purpose in the .44 Special. Lyman 429421 molds, throwing the well-known Keith Semiwadcutter bullets in both solid and hollowpoint forms, were acquired. The Keith Bullet, cast in a 1 in 15 tin-to-lead mixture, gives minimal leading problems in the .44 Special, and is fully as accurate as the gaschecked 429244 when care is taken in casting.

Some critics of the 429244 say that this gascheck bullet, designed by Ray Thompson, can’t be as accurate as a plain base bullet because the copper cup at its bottom prevents it from slugging out and forming a gas seal in the barrel. This, the detractors claim, allows hot gases to squeeze by the bearing surfaces of the slug, misshaping it and prematurely eroding the bore of the revolver. I have not found this to be so, and heartily recommend the gascheck version to everyone who is willing to go the extra trouble nad expense necessary to produce it. Because of the perfect bullet bases provided by the preshaped gaschecks, the Thompson guarantees accuracy, and I Supect still slugs out to form as good a gas seal as any plain base bullet.

I chose the Keith design because I found it possible, through careful casting, to produce bullets that would perform as well without the necessity of fiddling with the little copper cups.

Solid or hollowpoint, these forty-fours are deadly, and can’t be bettered as manstoppers by any cartridge other than the .44 and .41 magnums, equally properly loaded. My heavy load for police work or big game shooting is an easy one to put together. Size either the Thompson or Keith bullet to .429″ for Smith & Wesson or Ruger guns, .427″ for Colts. Seat this bullet over 17½ grains of Hercules 2400 powder and cap with CCI Magnum primers. If you can shoot a pistol, this load will arm you better than you would be with a 30-30 rifle.

This is a maximum load, and it is unlikely that it will be employed exclusively by men who shoot a great deal. For an intermediate cartridge of around 1,000 fps, 8½ grains of Unique serves well, and outperforms most factory pistol cartridges of any caliber. Charges of 6½ grains of 5066 or 5 grains of Bullseye with either the Lyman 429244 or 429421 bullets will give fine, about-factory-velocity, performance.

For normal to medium-heavy charges, almost any pistol, shotgun, or fast rifle powder may be used for the .44 Special. The Alcan and Red Dot Shotgun powders give singular performance, as well as such slow burners as Du Pont’s IMR4227. A comprehensive list of un-tempermental .44 loads will fill books.

The .44 Special is versatile. Although recommended by some of the more magnum-minded as being a fine deliverer of such small table game as cottontails, squirrels, and grouse, it is a bit severe on these edibles when loaded with full or semiwadcutter bullets, usually leaving a great deal of good meat mangled or bloodshot. Lyman, as well as other mold makers, offers several roundnosed bullet styles and weights that penetrate your entree with no more damage than a .38 Special

If making your own bullets holds no appeal, excellent commercial ones are available. The 240-grain Norma, jacketed in mild steel under a soft nose, serves well as an all-around number, although it doesn’t expand spectacularly at lower velocities. The various swaged bullets, with copper base cups covering their pure lead cores, are very good. Speer Bullets, among many others, merchandise an excellent .44 Semi-wadcutter. And don’t forget the super accurate factory load’s usefulness for small game. The cheapest cases for reloading can be obtained by fireing these loads that shoot so pleasantly.

I’m a little saddened by the fate of the .44 Special sixguns. My first custom Colt cost almost $200 just a few years ago. Acceding the rule of supply and demand, it was worth the price in terms of enjoyment and education. Smith & Wesson finally got some of their 1950 Target Models on dealer’s shelves in 1954. I bought one of the first, and immediately returned it to the factory to have its 6½” barrel cut to 5″ and a ramp front sight installed. The factory later offered these revolvers with 4″ barrels and ramp sights on special order, and they were a superb law enforcement weapon, selling at a discount to police officers. Hunter who knew handloading grabbed eagerly for these target-quality revolvers and recorded many big-game kills, form deer to Alaskan brown bear.

Scarcely two years of readily available .44 Specials were enjoyed by those who wanted them before the .44 Magnum was foaled in 1956. There can be no argument the the Big One did in all others who vied for top berth in the power department.

Remington’s sensational 240-grain lead bullet at 1500 fps gave even the most power-mad pistolero more than he bargained for. Whimpers were heard from effete shooters who allowed that shooting the .44 Magnum compared to the sensation of burning bamboo splinters being driven into the palm.

While touching off the Magnum is far from being that rough, it is true that few want to shoot a steady diet of full charge loads in it. It results in .44 Magnum shooters loading their big guns down to more palatable levels. A favorite “heavy” cartridge for .44 Magnum devotees is comprised of the Keith or Thompson bullet over 18 grains of Hercules 2400, although the acceptable maximum with these balls is 23 grains. This about duplicates the old, proven .44 Special handloads, and is, in truth, adequate for about any situation a six-shooter man may face.

Hearkening to their siren cry I bought every variation of the .44 Magnum that was commercially produced. In the process I rid myself of all my fine, proven .44 Special guns. Sheriff of a Texas County, I felt the need of a powerful holster gun, and dallied with the S & W .44 Magnum in 4″ length. With factory Magnum or full-powered handloads, its recoil was so pronounced (although not painful) as to make it a poor choice for strings of double action shots in combat situations. Loading it down rendered it no more potent than a .44 Special, and I soon traded it for one. Along with others, I hounded Smith & Wesson for a .41 Magnum, whose two factory loadings would bracket the needs of police officers who did not handload. Since introduction of this revolver in 1964, it has been the best choice for that purpose.

The .44 Magnum is odds-on the selection as a hunting handgun. Because that is what it is, there is small reason to ever load anything but heavy loads for it, and so is my Ruger loaded.

So now the fallen knight, the one-time expensive glamour boy can come out of hiding. Forty-four Specials dirt cheap, with used 1950 Military Smith & Wessons and rebuilt Colt New Service and Single Action Armies going for 50 to 60 bucks. Smith still makes their 1950 Target Models, but rumor has it they may stop. This will leave only the horse-and-buggy Colt single action available in that caliber, if you crave a brand new gun.

Cops need sidearms that will use powerful, store-bought ammunition, and thus should stick with the .357 and .41 Magnums. The everyday man who bolsters a handgun for come-what-may eventualities cannot improve on a .44 Special revolver.

If he owned a higher-priced .44 magnum, he would likely load it down to Special capabilities. With factory ammunition, the Special shoots as accurately as any revolver yet made. Although capable of taking any game that the Magnums can, the old .44 carries half the price of its Magnum “betters.”

A big, holstered sixgun is no longer part of my work, but when I get the chance, I roam in the brush country where a rattler, a whitetail buck, or a javelina might join me at any moment. I have a .44 Magnum, but my .44 Special seems more relaxed – and prettier. Buying a Colt New Frontier Model, with its beautiful blue and old style, mottled, casehardened colors took me back 15 years.

A lot of money is being spent by romantic types who want a big pistol and a little, lever action saddle carbine chambered for the same round. The general approach toward satisfying this craving is to have a Model 92 Winchester .44-40 rebarreled to handle .44 Magnum cartridges. This is expensive and results in a rifle very little more effective than it would have been with hot .44-40 loads. Further, the straight cases of the Magnum rounds often cause exasperating feeding problems in these little actions.

My solution is simpler – change the revolver instead of the rifle. Digging around in my bag of tricks, I fished out an old, but solid, .44-40 cylinder from a forgotten Colt single action. It slipped readily into battery in my sleek New Frontier Model, indexed crisply, and locked up tight. Groups fired with factory .44-40 ammo are adequately tight, opening up another career for my Frontier.

This finely fitted single action suits me well, and is the epitome of the forty-fours I dreamed of for fruitless years. At $150, it seems at first of little overpriced. But then – I once spent more.

Dark Canyon Home Page

I myself think that this is best article.