Peter J. Ortiz

| Pierre (Peter) Julien Ortiz | |

|---|---|

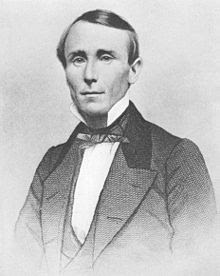

Colonel Peter J. Ortiz, U.S. Marine Corps

|

|

| Born | July 5, 1913 New York City |

| Died | May 16, 1988 (aged 74) |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | United States Marine Corps French Foreign Legion |

| Rank | Colonel, USMCR Acting Lieutenant, FFL |

| Battles/wars | French conquest of Morocco World War II |

| Awards | Navy Cross (2) Legion of Merit w/ Combat “V” Purple Heart Medal (2) American Campaign Medal EAME Campaign Medal (3) World War II Victory Medal Armed Forces Reserve Medal British Order of the British Empire French Légion d’Honneur French Médaille militaire French Croix de Guerre (5) French Médaille des Évadés French Croix du Combattant French Médaille Coloniale French Médaille des Blesses Order of Ouissam Alaouite |

Pierre (Peter) Julien OrtizOBE (July 5, 1913 – May 16, 1988) was a United States Marine Corps colonel who received two Navy Crossesfor extraordinary heroism as a major in World War II. He served in both North Africa and Europe throughout the war, as a member of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), operating behind enemy lines several times. He became an American film actor after the war.

Contents

[hide]

Military career[edit]

Although born in New York[1] to a Spanish-American mother[2] and French-American[3] father, Ortiz was educated at the University of Grenoble in France.[3] He spoke ten languages, including Spanish, French, German and Arabic.[2]

On February 1, 1932, at the age of 19, he joined the French Foreign Legion for five years’ service in North Africa.[2][3][4][5] He was sent first to the Legion’s training camp at Sidi Bel-Abbes, Algeria. He later served in Morocco, where he was promoted to corporal in 1933 and sergeant in 1935. He was awarded the Croix de guerre twice during a campaign against the Rif.[3] He also received the Médaille militaire.[5]An acting lieutenant, he was offered a commission as a second lieutenant if he would re-enlist.[5] Instead, when his contract expired in 1937, he went to Hollywood to serve as a technical adviser for war films.[3]

With the outbreak of World War II and the United States still neutral, he re-enlisted in the Foreign Legion in October 1939 as a sergeant, and received a battlefield commission in May 1940.[5] He was wounded while blowing up a fuel dump[5] and captured by the Germans during the 1940 Battle of France.[3] He escaped the following year via Lisbon and made his way to the United States.[5]

He enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps on June 22, 1942.[5] As a result of his training and experience, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant after only 40 days in service.[1][3] He was promoted to captain on December 3.[5] With his knowledge of the region, he was sent to Tangier, Morocco.[4] He conducted reconnaissance behind enemy lines in Tunisia for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).[3][5] At the time, though most of Morocco was a French protectorate, Tangiers was a protectorate of neutral Spain. During a night mission, Ortiz was seriously wounded in the right hand in an encounter with a German patrol and was sent back to the United States to recover.[5]

In 1943, Ortiz became a member of the OSS. On January 6, 1944, he was dropped by parachute into the Haute-Savoieregion of German-occupied France as part of the three-man “Union” mission, with Colonel Pierre Fourcaud of the French secret service and Captain Thackwaite from the British Special Operations Executive, to evaluate the capabilities of the Resistance in the Alpine region.[3][5] He drove four downed RAF pilots to the border of neutral Spain,[3] before leaving France with his team in late May. Promoted to major, Ortiz parachuted back into France on August 1, 1944, this time as the commander of the “Union II” mission.[3][5] He was captured by the Germans on August 16. In April 1945, he and three other prisoners of war escaped while being moved to another camp, but after ten days with little or no food, returned to their old camp after discovering that the prisoners had virtually taken control.[5] On April 29, the camp was liberated.

He rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Marine Corps Reserve. He was discharged from active duty in 1946 and returned to Hollywood. On March 1, 1955, he retired in the Marine Corps and received the rank of colonel on the retirement list because he was decorated in combat.[5] In April 1954, he volunteered to return to active duty to serve as a Marine observer in Indochina. The Marine Corps did not accept his request because “current military policies will not permit the assignment requested.”[5]

Later years[edit]

Upon returning to civilian life, Ortiz became an actor.[6] Ortiz appeared in a number of films, several with director John Ford, including Rio Grande, in which he played “Captain St. Jacques”. According to his son, Marine Lieutenant Colonel Peter J. Ortiz, Jr., “My father was an awful actor but he had great fun appearing in movies”.[3] At least two Hollywood films were based upon his personal exploits, 13 Rue Madeleine (1947) and Operation Secret (1952).[1]

Ortiz died of cancer on May 16, 1988, at the age of 74, and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. He was survived by his wife Jean and their son Peter J. Ortiz, Jr.[7]

Military decorations[edit]

Ortiz was the most highly decorated member of the OSS.[3] His decorations and medals include:

United States[edit]

- Navy Cross with gold star

- Legion of Merit with Combat “V”,

- Purple Heart with gold star

- Prisoner of War Medal

- Combat Action Ribbon (posthumous)

- American Campaign Medal

- European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal

- World War II Victory Medal

- Armed Forces Reserve Medal

United Kingdom[edit]

- Officer of the Order of the British Empire

France[edit]

- Chevalier (Knight) of the Legion of Honor

- Médaille militaire

- Croix de guerre des théâtres d’opérations extérieures with two palms

- Croix de Guerre 1939-1945 with three palms

- Croix du combattant

- Médaille des Évadés

- Médaille Coloniale

- Médaille des Blesses

- 1939–1945 Commemorative war medal (France)[5]

Morocco[edit]

[edit]

-

- Citation:

| “ | The Navy Cross is presented to Pierre (Peter) J. Ortiz, Major, U.S. Marine Corps (Reserve), for extraordinary heroism while attached to the United States Naval Command, Office of Strategic Services, London, England, in connection with military operations against an armed enemy in enemy-occupied territory, from January 8, to May 20, 1944. Operating in civilian clothes and aware that he would be subject to execution in the event of his capture, Major Ortiz parachuted from an airplane with two other officers of an Inter-Allied mission to reorganize existing Maquis groups in the region of Rhone. By his tact, resourcefulness and leadership, he was largely instrumental in affecting the acceptance of the mission by local resistance leaders, and also in organizing parachute operations for the delivery of arms, ammunition and equipment for use by the Maquis in his region. Although his identity had become known to the Gestapo with the resultant increase in personal hazard, he voluntarily conducted to the Spanish border four Royal Air Force officers who had been shot down in his region, and later returned to resume his duties. Repeatedly leading successful raids during the period of this assignment, Major Ortiz inflicted heavy casualties on enemy forces greatly superior in number, with small losses to his own forces. By his heroic leadership and astuteness in planning and executing these hazardous forays, Major Ortiz served as an inspiration to his subordinates and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.[8] | ” |

-

- Citation:

| “ | The Navy Cross is presented to Pierre (Peter) J. Ortiz, Major, U.S. Marine Corps (Reserve), for extraordinary heroism while serving with the Office of Strategic Services during operations behind enemy Axis lines in the Savoie Department of France, from August 1, 1944, to April 27, 1945. After parachuting into a region where his activities had made him an object of intensive search by the Gestapo, Major Ortiz valiantly continued his work in coordinating and leading resistance groups in that section. When he and his team were attacked and surrounded during a special mission designed to immobilize enemy reinforcements stationed in that area, he disregarded the possibility of escape and, in an effort to spare villagers severe reprisals by the Gestapo, surrendered to this sadistic Geheim Staats Polizei. Subsequently imprisoned and subjected to numerous interrogations, he divulged nothing, and the story of this intrepid Marine Major and his team became a brilliant legend in that section of France where acts of bravery were considered commonplace. By his outstanding loyalty and self-sacrificing devotion to duty, Major Ortiz contributed materially to the success of operations against a relentless enemy, and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.[8] | ” |

Other honors[edit]

In August 1994, Centron, France held a ceremony in which the town center was renamed “Place Colonel Peter Ortiz”.[7]

Partial filmography[edit]

- Task Force (1949) (uncredited)

- She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) (uncredited)

- Twelve O’Clock High (1949) (uncredited)

- Abbott and Costello in the Foreign Legion (1950) (uncredited)

- Rio Grande (1950)

- Sirocco (1951) (uncredited)

- Flying Leathernecks (1951) (uncredited)

- Retreat, Hell! (1952)

- What Price Glory (1952) (uncredited)

- Blackbeard the Pirate (1952) (uncredited)

- The Desert Rats (1953) (uncredited)

- King Richard and the Crusaders (1954)

- 7th Cavalry (1956)

- The Halliday Brand (1957)

- The Wings of Eagles (1957) (uncredited)

Here is another Wild Man that really tore up the local scene.William Walker (filibuster)

This article may be unbalanced towards certain viewpoints. (November 2016)

William Walker President of the Republic of Nicaragua In office

July 12, 1856 – May 1, 1857Preceded by Patricio Rivas Succeeded by Máximo Jerez and Tomás Martínez 1st President of the Republic of Sonora In office

January 21, 1854 – May 8, 18541st President of the Republic of Lower California In office

November 3, 1853 – January 21, 1854Personal details Born May 8, 1824

Nashville, TennesseeDied September 12, 1860 (aged 36)

Trujillo, HondurasPolitical party Democratic (Nicaragua) Signature William Walker (May 8, 1824 – September 12, 1860) was an American physician, lawyer, journalist and mercenary who organized several private military expeditions into Latin America, with the intention of establishing English-speaking colonies under his personal control, an enterprise then known as “filibustering.” Walker usurped the presidency of the Republic of Nicaragua in 1856 and ruled until 1857, when he was defeated by a coalition of Central American armies. He was executed by the government of Honduras in 1860.

Contents

[hide]

Early life[edit]

Walker was born in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1824 to James Walker and his wife Mary Norvell. His father was a son of a Scottish immigrant. His mother was a daughter of Lipscomb Norvell, an American Revolutionary War officer from Virginia. One of Walker’s maternal uncles was John Norvell, a US Senator from Michigan and founder of The Philadelphia Inquirer.[1] William Walker was engaged to Helen Martin, but they never married, and he died without any children.

William Walker graduated summa cum laude from the University of Nashvilleat the age of fourteen.[1] He studied medicine at the University of Edinburghand University of Heidelberg before receiving his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania at the age of 19. He practiced briefly in Philadelphia before moving to New Orleans to study law.[2]

He practiced law for a short time, and then quit to become co-owner and editor of the New Orleans Crescent. In 1849, he moved to San Francisco, where he was a journalist and fought three duels; he was wounded in two of them. Walker then conceived the idea of conquering vast regions of Latin America and creating new slave states to join those already part of the United States.[3] These campaigns were known as filibustering or freebooting.Duel with William Hicks Graham[edit]

William Walker first gained national attention after his duel with William Hicks Graham on January 12, 1851 in San Francisco.[4] At that time, Walker was the editor of the San Francisco Herald while Graham was a clerk in the employ of Judge R. N. Morrison. The conflict started after Walker criticized Graham and his colleagues in the newspapers, which angered and prompted Graham to challenge Walker to a duel.[5] Graham was a notorious gunman and duellist in his time, having taken part in a number of duels and shootouts in the Old West. Walker on the other hand, had experience duelling with single-shot pistols at one time, but his duel with Graham was to be fought with revolvers.[citation needed]

The combatants met at Mission Dolores and each were given Colt Dragoons with 5 shots. They stood face-to-face at ten paces, and with the signal of a referee, quickly aimed and tried to fire their revolvers. Graham managed to fire two bullets, hitting Walker in his pantaloons and his thigh, seriously wounding him. Walker, though he tried a number of times to shoot his weapon during the duel, failed to fire even a single shot and Graham was left unscathed. The duel ended after the wounded Walker finally conceded, and afterwards Graham was arrested but was quickly released. The duel was recorded in The Daily Alta California.[6]Expedition to Mexico[edit]

In the summer of 1853, Walker traveled to Guaymas, seeking a grant from the government of Mexico to create a colony, using the pretext that it would serve as a fortified frontier, protecting US soil from Indian raids. Mexico refused, and Walker returned to San Francisco determined to obtain his colony, regardless of Mexico’s position. He began recruiting from amongst American supporters of slavery and the Manifest Destiny Doctrine, mostly inhabitants of Kentucky and Tennessee. His intentions then changed from forming a buffer colony to establishing an independent Republic of Sonora, which might eventually take its place as a part of the American Union (as had been the case previously with the Republic of Texas). He funded his project by “selling scrips which were redeemable in lands of Sonora.”[2]

On October 15, 1853, Walker set out with 45 men to conquer the Mexican territories of Baja California Territory and Sonora State. He succeeded in capturing La Paz, the capital of sparsely populated Baja California, which he declared the capital of a new Republic of Lower California, with himself as president and his partner, Watkins, as vice president; he then put the region under the laws of the American state of Louisiana, which made slavery legal.[citation needed] Fearful of attacks by Mexico, Walker moved his headquarters twice over the next three months, first to Cabo San Lucas, and then further north to Ensenada to maintain a more secure position of operations, because he lost to General Manuel Márquez de León. Although he never gained control of Sonora, less than three months later, he pronounced Baja California part of the larger Republic of Sonora.[2] Lack of supplies and strong resistance by the Mexican government quickly forced Walker to retreat.[citation needed]

Back in California, he was put on trial for conducting an illegal war, in violation of the Neutrality Act of 1794. Nevertheless, in the era of Manifest Destiny, his filibustering project was popular in the southern and western United States and the jury took eight minutes to acquit him.[7][8]Conquest of Nicaragua[edit]

Since there was no inter-oceanic route joining the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans at the time, and the transcontinental railway did not yet exist, a major trade route between New York City and San Francisco ran through southern Nicaragua. Ships from New York entered the San Juan River from the Atlantic and sailed across Lake Nicaragua. People and goods were then transported by stagecoach over a narrow strip of land near the city of Rivas, before reaching the Pacific and being shipped to San Francisco. The commercial exploitation of this route had been granted by Nicaragua to the Accessory Transit Company, controlled by shipping magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt (see alsoNicaragua Canal).[9]

In 1854, a civil war erupted in Nicaragua between the Legitimist Party (also called the Conservative Party), based in the city of Granada, and the Democratic Party(also called the Liberal Party), based in León. The Democratic Party sought military support from Walker who, to circumvent U.S. neutrality laws, obtained a contract from Democratic president Francisco Castellón to bring as many as three hundred colonists to Nicaragua. These mercenaries received the right to bear arms in the service of the Democratic government. Walker sailed from San Francisco on May 3, 1855, with approximately 60 men. Upon landing, the force was reinforced by 110 locals.[10][11] Within Walker’s expeditionary force was the well-known explorer and journalist Charles Wilkins Webber as well as the English adventurer Charles Frederick Henningsen, a veteran of the First Carlist War, the Hungarian Revolution, and the war in Circassia.[12]

With Castellón’s consent, Walker attacked the Legitimists in the town of Rivas, near the trans-isthmian route. He was driven off, but not without inflicting heavy casualties. In this First Battle of Rivas a school teacher called Enmanuel Mongalo y Rubio (1834-1872) burned the Filibusters Headquarter. On September 4, during the Battle of La Virgen, Walker defeated the Legitimist army. On October 13, he conquered the Legitimist capital of Granada and took effective control of the country. Initially, as commander of the army, Walker ruled Nicaragua through provisional President Patricio Rivas.[13]U.S. President Franklin Pierce recognized Walker’s regime as the legitimate government of Nicaragua on May 20, 1856.[14] Walker’s first ambassadorial appointment, Colonel Parker H. French, was refused recognition.[15]

Walker’s actions in the region caused concern amongst his neighbors and potential American and European investors who feared he may pursue further military conquests in Central America. Concerned of Walker’s intentions in the region, Costa Rican President Juan Rafael Mora rejected Walker’s diplomatic overtures and began preparing the country’s military for a potential conflict.[16] The most important strategic defeat of Walker came during the Campaign of 1856–57 when the Costa Rican army, led by President Juan Rafael Mora defeated the Filibusters, in Rivas, Nicaragua on April 11, 1856, (the Second battle of Rivas). It was in this battle that the soldier and drummer Juan Santamaría sacrificed himself by setting the filibuster stronghold on fire. In an amazing parallel between these two Central American countries, Santamaría would become Costa Rica’s national hero. Walker deliberately contaminated the water wells of Rivas with corpses. Later, the morbus cholera epidemic spread to the Costa Ricans troops and the civilian population of the city of Rivas. A few months later nearly 10,000 civilians died, almost the 10% of the population of Costa Rica.[17][18]

Meanwhile, C. K. Garrison and Charles Morgan, subordinates of Cornelius Vanderbilt’s Accessory Transit Company, provided financial and logistic assistance to the filibusters in exchange for Walker, as ruler of Nicaragua, seizing the Company’s property (on the pretext of a charter violation) and turning it over to Garrison and Morgan. Outraged, Vanderbilt dispatched two secret agents to the Costa Rican government with plans to fight Walker. They would help regain control of Vanderbilt’s steamboats which had become a logistical lifeline for Walker’s army.[19]

Walker organized a battalion of four companies, of which one was composed by Germans, a second by Frenchmen and the other two by Americans totaling 240 men placed under the command of Colonel Schlessinger to invade Costa Rica in a preemptive action, but this advance force was defeated at the Battle of Santa Rosa in March 20, 1856. In April 1856, Costa Rican troops, -conducted by President Juan Rafael Mora, General José Joaquín Mora Porras, and the General José María Cañas (1809-1860) who was a Salvadoran militar who was brother-in-law of President J.R. Mora and a Costa Rican citizen and later also a National heroe-, entered into Nicaraguan territory and inflicted a defeat on Walker’s men at the Second Battle of Rivas on April 11, in which Juan Santamaría, later to be recognized as one of Costa Rica’s national heroes, played a key role by burning Filibuster´s Headquarters (he dies in this heroic action).[20]From the north, President José Santos Guardiola also sent Honduran troops who went side by side with Salvadoran troops to fight William Walker under the leadership of the Xatruch brothers. First, Florencio Xatruch was leading his troops against Walker and the filibusters in la Puebla, Rivas. But later, and because of the opposition of other Central American armies, General José Joaquín Mora Porras, brother of Juan Rafael Mora Porras (President of Costa Rica), was made Commandant General-in-Chief of the Allied Armies of Central America in the Third Battle of Rivas (April, 1857).

The leader of all this heroic Campaign, was the Costa Rican President, Juan Rafael Mora, who later was deposed as the Constitutional President in a coup d´état by the Oligarchy, and later brutally shot in Puntarenas, Costa Rica, on 1860 with his supporters General Cañas and his own brother General José Joaquín Mora Porras.[21]

Since those days, Central America was in Civil War, so Honduras and El Salvador recognized Xatruch as Brigade and Division General. On June 12, 1857, Xatruch certainly made a triumphant entrance to Comayagua, which was then the capital of Honduras, after Walker surrendered. The nickname by which Hondurans are known popularly still today, Catracho, and the more infamous nickname Salvadorans are known today, Salvatrucho are derived from Xatruch’s figure and successful campaign as leader of the Allied Armies of Central America, as the troops of El Salvador and Honduras were national heroes, fighting side by side as Central American brothers against William Walker’s troops.

As the general and his soldiers returned from battle, some Nicaraguans affectionately yelled out “¡Vienen los xatruches!;” meaning, Here come Xatruch’s boys! Nevertheless, Nicaraguans had so much trouble pronouncing the general’s last name (a North-Eastern Spanish last name, like Guardiola) that they altered the phrase to “los catruches” and ultimately settled on “los catrachos.”[22]

Of course, a key historical role was played by the Costa Rican Army in unifying the other Central American armies to fight against Filibusters. The “Campaign of the Transit” (1857), was the name given by Costa Rican historians to the groups of several battles fought by the Costa Rican army, supervised by Colonel Salvador Mora, and lead heroically “in situ” by Colonel Blanco and Colonel Salazar at the San Juan River. By establishing control of this binational river at its border with Nicaragua, Costa Rica prevented any military reinforcements from reaching Walker and his Filibuster troops via the Caribbean Sea. Also Costa Rican diplomacy neutralized US official support for Walker by taking advantage of the dispute between the magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt and William Walker. See also:[23][24] Walker’s house in Granada. On October 12, 1856, during the siege of Granada, Guatemalan officer José Víctor Zavala ran under heavy fire to capture the flag and bring it back to the Central American coalition army trenches shouting Filibuster bullets don’t kill! Zavala survived this adventure unscathed.[25]

Walker’s house in Granada. On October 12, 1856, during the siege of Granada, Guatemalan officer José Víctor Zavala ran under heavy fire to capture the flag and bring it back to the Central American coalition army trenches shouting Filibuster bullets don’t kill! Zavala survived this adventure unscathed.[25]Walker took up residence in Granada and set himself up as President of Nicaragua, after conducting a fraudulent election. He was inaugurated on July 12, 1856, and soon launched an Americanization program, reinstating slavery, declaring English an official language and reorganizing currency and fiscal policy to encourage immigration from the United States. Realizing that his position was becoming precarious, he sought support from the Southerners in the U.S. by recasting his campaign as a fight to spread the institution of black slavery, which many American Southern businessmen saw as the basis of their agrarian economy. With this in mind, Walker revoked Nicaragua’s emancipation edict of 1821. This move did increase Walker’s popularity in the South and attracted the attention of Pierre Soulé, an influential New Orleans politician, who campaigned to raise support for Walker’s war. Nevertheless, Walker’s army was weakened by massive defections and an epidemic of cholera (probably created by Walker himself when he ordered that the water wells in Rivas and perhaps Granada be contaminated with dead bodies), finally was defeated by the Central American coalition led by Costa Rican President Juan Rafael Mora Porras (1814-1860).

On October 12, 1856, Guatemalan Colonel José Víctor Zavala performed an act of courage: he crossed the square of the city to the house where Walker soldiers took shelter; under heavy fire, he made it to the enemy’s flag and carried it back with him shouting to his men that the Filibuster bullets did not kill.[25]

On December 14, 1856, as Granada was surrounded by 4,000 Costa Rican, Honduran, Salvadoran and Guatemalan troops, Charles Frederick Henningsen, one of Walker’s generals, ordered his men to set the city ablaze before escaping and fighting their way to Lake Nicaragua. When retreating from Granada, the oldest Spanish colonial city in Nicaragua, he left a detachment with orders to level it in order to instill, as he put it, “a salutary dread of American justice.” It took them over two weeks to smash, burn and flatten the city, but flatten it they did; all that remained were inscriptions on the ruins that read “Aqui Fue Granada” (“Here Was Granada”).[26]

On May 1, 1857, Walker surrendered to Commander Charles Henry Davis of the United States Navy under the pressure of Costa Rica and the Central American armies, and was repatriated. Upon disembarking in New York City, he was greeted as a hero, but he alienated public opinion when he blamed his defeat on the U.S. Navy. Within six months, he set off on another expedition, but he was arrested by the U.S. Navy Home Squadron under the command of Commodore Hiram Paulding and once again returned to the U.S. amid considerable public controversy over the legality of the Navy’s actions.[27]Death in Honduras[edit]

After writing an account of his Central American campaign (published in 1860 as War in Nicaragua), Walker once again returned to the region. British colonists in Roatán, in the Bay Islands, fearing that the government of Honduras would move to assert its control over them, approached Walker with an offer to help him in establishing a separate, English-speaking government over the islands. Walker disembarked in the port city of Trujillo, but soon fell into the custody of Commander Nowell Salmon (later Admiral Sir Nowell Salmon) of the British Royal Navy. The British government controlled the neighboring regions of British Honduras (now Belize) and the Mosquito Coast (now part of Nicaragua) and had considerable strategic and economic interest in the construction of an inter-oceanic canal through Central America. It therefore regarded Walker as a menace to its own affairs in the region.[28]

Rather than return him to the US, for reasons that remain unclear, Salmon sailed to Trujillo and delivered Walker to the Honduran authorities, together with his chief of staff, Colonel A. F. Rudler. Rudler was sentenced to 4 years in the mines, but Walker was sentenced to death, and executed by firing squad, near the site of the present-day hospital, on September 12, 1860.[29] Walker was 36 years old. He is buried in the Old Cemetery, in Trujillo.Influence and reputation[edit]

William Walker convinced many Southerners of the desirability of creating a slave-holding empire in tropical Latin America. In 1861, when U.S. Senator John J. Crittenden proposed that the 36°30′ parallel north be declared as a line of demarcation between free and slave territories, some Republicans denounced such an arrangement, saying that it “would amount to a perpetual covenant of war against every people, tribe, and State owning a foot of land between here and Tierra del Fuego.”[30]

Before the end of the American Civil War, Walker’s memory enjoyed great popularity in the southern and western United States, where he was known as “General Walker” and as the “grey-eyed man of destiny.” Northerners, on the other hand, generally regarded him as a pirate. Despite his intelligence and personal charm, Walker consistently proved to be a limited military and political leader. Unlike men of similar ambition, such as Cecil Rhodes, Walker’s grandiose scheming ultimately failed against the union of Central American people.

In Central American countries, the successful military campaign of 1856–57 against William Walker became a source of national pride and identity, and it was later promoted by local historians and politicians as substitute for the war of independence that Central America had not experienced. April 11 is a Costa Rican national holiday in memory of Walker’s defeat at Rivas. Juan Santamaría, who played a key role in that battle, is honored as one of the two Costa Rican national heroes, the other one being Juan Rafael Mora himself.That William Walker is a little-known figure in American history, evidenced in 1988 when President George H.W. Bush carefully chose the new ambassador for El Salvador to ease tensions following the Central American Crisis. The appointee’s name was William Walker. Now I very much doubt that a Character like Gen Puller would be able to survive and thrive in today’s Military. But I hope that I am wrong!

Now I very much doubt that a Character like Gen Puller would be able to survive and thrive in today’s Military. But I hope that I am wrong!Chesty Puller

“Chesty” Born June 26, 1898

West Point, Virginia, U.S.Died October 11, 1971 (aged 73)

Hampton, Virginia, U.S.Buried Christchurch Parish Cemetery

Christ Church, Saluda, Virginia, U.S.Allegiance United States of America

Service/branch United States Marine Corps

Years of service 1918–1955 Rank Lieutenant General

Unit 1st Marine Division Commands held World War II: 1st Battalion, 7th Marines and 1st Marines

Korean War: 1st MarinesBattles/wars Banana Wars Awards Navy Cross (5)

Distinguished Service Cross

Silver Star

Legion of Merit (2),

“V” Device

Bronze Star ,

“V” Device

Purple Heart

Air Medal (3)

Spouse(s) Virginia Montague Evans Relations Lewis Burwell Puller, Jr. (son) Lewis Burwell “Chesty” Puller (June 26, 1898 – October 11, 1971) was a United States Marine Corpslieutenant general who fought guerrillas in Haiti and Nicaragua, and fought in World War II and the Korean War.

Puller is the most decorated Marine in American history. He is one of two U.S. servicemen to be awarded five Navy Crosses and, with the Distinguished Service Cross awarded to him by the U.S. Army, his total of six stands only behind Eddie Rickenbacker‘s eight times receiving the nation’s second-highest military award for valor.[1]

Puller retired from the Marine Corps with 37 years of service in 1955 and lived in Virginia.Contents

[hide]

Early life[edit]

Puller was born in West Point, Virginia, to Matthew and Martha Puller. His father was a grocer who died when Lewis was 10 years old. Puller grew up listening to old veterans’ tales of the American Civil War and idolizing Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. He wanted to enlist in the United States Army to fight in the Border War with Mexico in 1916, but he was too young and could not get parental consent from his mother.[2]

The following year, Puller attended the Virginia Military Institute but left in August 1918 as World War I was still ongoing, saying that he wanted to “go where the guns are!”[3] Inspired by the 5th Marines at Belleau Wood, he enlisted in the United States Marine Corps as a private and attended boot camp at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, South Carolina.[2]

Although he never saw action in that war, the Marine Corps was expanding, and soon after graduating he attended their non-commissioned officer school and Officer Candidates School(OCS) at Quantico, Virginia, following that. Graduating from OCS on June 16, 1919, Puller was appointed a second lieutenant in the reserves, but the reduction in force from 73,000 to 1,100 officers and 27,400 men[4] following the war led to his being put on inactive status 10 days later and given the rank of corporal.[2]Interwar years[edit]

Corporal Puller received orders to serve in the Gendarmerie d’Haiti as a lieutenant, seeing action in Haiti.[5] While the United States was working under a treaty with Haiti, he participated in over forty engagements during the ensuing five years against the Caco rebels and attempted to regain his commission as an officer twice. In 1922, he served as an adjutant to Major Alexander Vandegrift, a future Commandant of the Marine Corps.

Puller returned stateside and was finally recommissioned as a second lieutenant on March 6, 1924 (Service No. 03158), afterward completing assignments at the Marine Barracks in Norfolk, Virginia, The Basic School in Quantico, Virginia, and with the 10th Marine Artillery Regiment in Quantico, Virginia. He was assigned to the Marine Barracks at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in July 1926 and in San Diego, California, in 1928.In December 1928, Puller was assigned to the NicaraguanNational Guarddetachment, where he was awarded his first Navy Cross for his actions from February 16 to August 19, 1930, when he led “five successive engagements against superior numbers of armed bandit forces.” He returned stateside in July 1931 and completed the year-long Company Officers Course at Fort Benning, Georgia, thereafter returning to Nicaragua from September 20 to October 1, 1932, and was awarded a second Navy Cross. Puller led American Marines and Nicaraguan National Guardsmen into battle against Sandinista rebels in the last major engagement of the Sandino Rebellion near El Sauce on December 26, 1932.

After his service in Nicaragua, Puller was assigned to the Marine detachment at the American Legation in Beijing, China, commanding a unit of China Marines. He then went on to serve aboard USS Augusta, a cruiser in the Asiatic Fleet, which was commanded by then-Captain Chester W. Nimitz. Puller returned to the States in June 1936 as an instructor at The Basic School in Philadelphia, where he trained Ben Robertshaw, Pappy Boyington, and Lew Walt.[6]

In May 1939, he returned to the Augusta as commander of the on-board Marine detachment, and then back to China, disembarking in Shanghai in May 1940 to serve as the executive officer and commanding officer of 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines (2/4) until August 1941. Major Puller returned to the U.S. on August 28, 1941. After a short leave, he was given command of 1st Battalion, 7th Marines (1/7) of the 1st Marine Division, stationed at New River, North Carolina (later Camp Lejeune).[7]World War II[edit]

Early in the Pacific theater the 7th Marines formed the nucleus of the newly created 3rd Marine Brigade and arrived to defend Samoa on May 8, 1942. Later they were redeployed from the brigade and on September 4, 1942, they left Samoa and rejoined the 1st Division at Guadalcanal on September 18, 1942.

Soon after arriving on Guadalcanal, Puller led his battalion in a fierce action along the Matanikau, in which Puller’s quick thinking saved three of his companies from annihilation. In the action, these companies were surrounded and cut off by a larger Japanese force. Puller ran to the shore, signaled a United States Navy destroyer, the USS Ballard (DD-267),[8] and then Puller directed the destroyer to provide fire support while landing craft rescued his Marines from their precarious position. U.S. Coast Guard Signalman First Class Douglas Albert Munro—Officer-in-Charge of the group of landing craft, was killed while providing covering fire from his landing craft for the Marines as they evacuated the beach and was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for the action, to date the only Coast Guardsman to receive the decoration. Puller, for his actions, was awarded the Bronze Star Medal with Combat “V”.

Later on Guadalcanal, Puller was awarded his third Navy Cross, in what was later known as the “Battle for Henderson Field“. Puller commanded 1st Battalion 7th Marines (1/7), one of two American infantry units defending the airfield against a regiment-strength Japanese force. The 3rd Battalion of the U.S. Army’s 164th Infantry Regiment (3/164) fought alongside the Marines. In a firefight on the night of October 24–25, 1942, lasting about three hours, 1/7 and 3/164 sustained 70 casualties; the Japanese force suffered over 1,400 killed in action, and the Americans held the airfield. He nominated two of his men (one being Sgt. John Basilone) for Medals of Honor. He was wounded himself on November 9.

Puller was then made executive officer of the 7th Marine Regiment. While serving in this capacity at Cape Gloucester, Puller was awarded his fourth Navy Cross for overall performance of duty between December 26, 1943, and January 19, 1944. During this time, when the battalion commanders of 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines (3/7) and later, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines (3/5), were under heavy machine gun and mortar fire, he expertly reorganized the battalion and led the successful attack against heavily fortified Japanese defensive positions. He was promoted to colonel effective February 1, 1944, and by the end of the month had been named commander of the 1st Marine Regiment. In September and October 1944, Puller led the 1st Marine Regiment into the protracted battle on Peleliu, one of the bloodiest battles in Marine Corps history, and received his first of two Legion of Merit awards. The 1st Marines under Puller’s command lost 1,749 out of approximately 3,000 men, but these losses did not stop Puller from ordering frontal assaults against the well-entrenched enemy. The corps commander had to order the 1st Marine Division commanding general to pull the annihilated 1st Marine Regiment out of the line.[9]

During the summer of 1944, Puller’s younger brother, Samuel D. Puller, the Executive Officer of the 4th Marine Regiment, was killed by an enemy sniper on Guam.[10]

Puller returned to the United States in November 1944, was named executive officer of the Infantry Training Regiment at Camp Lejeune and, two weeks later, Commanding Officer. After the war, he was made Director of the 8th Reserve District at New Orleans, and later commanded the Marine Barracks at Pearl Harbor.Korean War[edit]

At the outbreak of the Korean War, Puller was once again assigned as commander of the First Marine Regiment. He participated in the landing at Inchon on September 15, 1950, and was awarded the Silver Star Medal.[11] For leadership from September 15 through November 2, he was awarded his second Legion of Merit. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross from the U.S. Army for heroism in action from November 29 to December 4, and his fifth Navy Cross for heroism during December 5–10, 1950, at the Battle of Chosin Reservoir. It was during that battle that he said the famous line, “We’ve been looking for the enemy for some time now. We’ve finally found him. We’re surrounded. That simplifies things.”[12]

In January 1951, Puller was promoted to brigadier general and was assigned duty as assistant division commander (ADC) of the 1st Marine Division. On February 24, however, his immediate superior, Major General O.P. Smith, was hastily transferred to command IX Corps when its Army commander, Major General Bryant Moore, died. Smith’s transfer left Puller temporarily in command of the 1st Marine Division until sometime in March. He completed his tour of duty as assistant commander and left for the United States on May 20, 1951.[13] He took command of the 3rd Marine Division at Camp Pendleton, California until January 1952, and then was assistant commander of the division until June 1952. He then took over Troop Training Unit Pacific at Coronado, California. In September 1953, he was promoted to major general.Post-Korean War[edit]

In July 1954, Puller took command of the 2nd Marine Division at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina until February 1955 when he became Deputy Camp Commander. He suffered a stroke,[14] and was retired by the Marine Corps on November 1, 1955 with a tombstone promotion to lieutenant general.[15]

Regarding his nickname, in a handwritten addition to a typed 22 November 1954 letter to Maj. Frank C. Sheppard, Puller wrote, “I agree with you 100%. I had done a little soldiering previous to Guadalcanal and had been called a lot of names, but why ‘Chesty’? Especially the steel part??”[16]Relations[edit]

Puller’s son, Lewis Burwell Puller, Jr. (generally known as Lewis Puller), served as a Marine lieutenant in the Vietnam War. While serving with 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines (2/1), Lewis Jr. was severely wounded by a mine explosion, losing both legs and parts of his hands. Lieutenant General Puller broke down sobbing at seeing his son for the first time in the hospital.[17] Lewis Jr. won a 1992 Pulitzer Prize for his autobiography Fortunate Son: The Healing of a Vietnam Vet.

Puller was father-in-law to Colonel William H. Dabney, USMC (Retired), a Virginia Military Institute (VMI) graduate, who was the commanding officer (then Captain) of two heavily reinforced rifle companies of the Third Battalion, Twenty-Sixth Marines (3/26) from January 21 to April 14, 1968 in Vietnam. During the entire period, Colonel Dabney’s force stubbornly defended Hill 881S, a regional outpost vital to the defense of the Khe Sanh Combat Base during the 77-day siege. Following Khe Sanh, Dabney was recommended for the Navy Cross for his actions on Hill 881 South, but his battalion executive officer’s helicopter carrying the recommendation papers crashed—and the papers were lost. It was not until April 15, 2005, that Colonel Dabney received the Navy Cross during an award ceremony at Virginia Military Institute.

Puller was a distant cousin to the famous U.S. Army General George S. Patton.[18]

He was an Episcopalian and parishioner of Christ Church Parish and is buried in the historic cemetery next to his wife Virginia Montague Evans.[19]Decorations and awards[edit]

Puller received the second-highest U.S. military award six times (one of only two persons so honored): five Navy Crosses and one U.S. Army Distinguished Service Cross. He was the second of two U.S. servicemen to ever receive five Navy Crosses, U.S. Navy submarine commander Roy Milton Davenport was the first to receive five Navy Crosses.

Puller’s military awards include:

[edit]

Citation:

“For distinguished service in the line of his profession while commanding a Nicaraguan National Guard patrol. First Lieutenant Lewis B. Puller, United States Marine Corps, successfully led his forces into five successful engagements against superior numbers of armed bandit forces; namely, at LaVirgen on 16 February 1930, at Los Cedros on 6 June 1930, at Moncotal on 22 July 1930, at Guapinol on 25 July 1930, and at Malacate on 19 August 1930, with the result that the bandits were in each engagement completely routed with losses of nine killed and many wounded. By his intelligent and forceful leadership without thought of his own personal safety, by great physical exertion and by suffering many hardships, Lieutenant Puller surmounted all obstacles and dealt five successive and severe blows against organized banditry in the Republic of Nicaragua.”[21]

[edit]

Citation:

“First Lieutenant Lewis B. Puller, United States Marine Corps (Captain, Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua) performed exceptionally meritorious service in a duty of great responsibility while in command of a Guardia Patrol from 20 September to 1 October 1932. Lieutenant Puller and his command of forty Guardia and Gunnery Sergeant William A. Lee, United States Marine Corps, serving as a First Lieutenant in the Guardia, penetrated the isolated mountainous bandit territory for a distance of from eighty to one hundred miles north of Jinotega, his nearest base. This patrol was ambushed on 26 September 1932, at a point northeast of Mount Kilambe by an insurgent force of one hundred fifty in a well-prepared position armed with not less than seven automatic weapons and various classes of small arms and well-supplied with ammunition. Early in the combat, Gunnery Sergeant Lee, the Second in Command, was seriously wounded and reported as dead. The Guardia immediately behind Lieutenant Puller in the point was killed by the first burst of fire, Lieutenant Puller, with great courage, coolness and display of military judgment, so directed the fire and movement of his men that the enemy were driven first from the high ground on the right of his position, and then by a flanking movement forced from the high ground to the left and finally were scattered in confusion with a loss of ten killed and many wounded by the persistent and well-directed attack of the patrol. The numerous casualties suffered by the enemy and the Guardia losses of two killed and four wounded are indicative of the severity of the enemy resistance. This signal victory in jungle country, with no lines of communication and a hundred miles from any supporting force, was largely due to the indomitable courage and persistence of the patrol commander. Returning with the wounded to Jinotega, the patrol was ambushed twice by superior forces on 30 September. On both of the occasions the enemy was dispersed with severe losses.”[21]

[edit]

Citation:

“For extraordinary heroism as Commanding Officer of the First Battalion, Seventh Marines, First Marine Division, during the action against enemy Japanese forces on Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, on the night of 24 to 25 October 1942. While Lieutenant Colonel Puller’s battalion was holding a mile-long front in a heavy downpour of rain, a Japanese force, superior in number, launched a vigorous assault against that position of the line which passed through a dense jungle. Courageously withstanding the enemy’s desperate and determined attacks, Lieutenant Colonel Puller not only held his battalion to its position until reinforcements arrived three hours later, but also effectively commanded the augmented force until late in the afternoon of the next day. By his tireless devotion to duty and cool judgment under fire, he prevented a hostile penetration of our lines and was largely responsible for the successful defense of the sector assigned to his troops.”[21]

[edit]

Citation:

“For extraordinary heroism as Executive Officer of the Seventh Marines, First Marine Division, serving with the Sixth United States Army, in combat against enemy Japanese forces at Cape Gloucester, New Britain, from 26 December 1943 to 19 January 1944. Assigned temporary command of the Third Battalion, Seventh Marines, from 4 to 9 January, Lieutenant Colonel Puller quickly reorganized and advanced his unit, effecting the seizure of the objective without delay. Assuming additional duty in command of the Third Battalion, Fifth Marines, from 7 to 8 January, after the commanding officer and executive officer had been wounded, Lieutenant Colonel Puller unhesitatingly exposed himself to rifle, machine-gun and mortar fire from strongly entrenched Japanese positions to move from company to company in his front lines, reorganizing and maintaining a critical position along a fire-swept ridge. His forceful leadership and gallant fighting spirit under the most hazardous conditions were contributing factors in the defeat of the enemy during this campaign and in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”[21]

[edit]

Citation:

“For extraordinary heroism as Commanding Officer of the First Marines, First Marine Division (Reinforced), in action against aggressor forces in the vicinity of Koto-ri, Korea, from 5 to 10 December 1950. Fighting continuously in sub-zero weather against a vastly outnumbering hostile force, Colonel Puller drove off repeated and fanatical enemy attacks upon his Regimental defense sector and supply points. Although the area was frequently covered by grazing machine-gun fire and intense artillery and mortar fire, he coolly moved along his troops to insure their correct tactical employment, reinforced the lines as the situation demanded, and successfully defended the perimeter, keeping open the main supply routes for the movement of the Division. During the attack from Koto-ri to Hungnam, he expertly utilized his Regiment as the Division rear guard, repelling two fierce enemy assaults which severely threatened the security of the unit, and personally supervised the care and prompt evacuation of all casualties. By his unflagging determination, he served to inspire his men to heroic efforts in defense of their positions and assured the safety of much valuable equipment which would otherwise have been lost to the enemy. His skilled leadership, superb courage and valiant devotion to duty in the face of overwhelming odds reflect the highest credit upon Colonel Puller and the United States Naval Service.”[21]

Distinguished Service Cross citation[edit]

Citation:

“The President of the United States of America, under the provisions of the Act of Congress approved July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Colonel Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller (MCSN: 0-3158), United States Marine Corps, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy of the United Nations while serving as Commanding Officer, First Marines, FIRST Marine Division (Reinforced), in action against enemy aggressor forces in the vicinity of the Chosin Reservoir, Korea, during the period 29 November to 4 December 1950. Colonel Puller’s actions contributed materially to the breakthrough of the First Marine Regiment in the Chosin Reservoir area and are in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service.”

Cornelius C. Smith

Cornelius C. Smith  Cornelius C. Smith displaying his Medal of Honor.

Cornelius C. Smith displaying his Medal of Honor.Born April 7, 1869

Tucson, Arizona Territory, United StatesDied January 10, 1936 (aged 66)

Riverside, CaliforniaPlace of burial Evergreen Memorial Park Allegiance United States of America Service/branch United States Army Years of service 1889–1920 Rank Colonel Unit 4th U.S. Cavalry

2nd U.S. Cavalry

6th U.S. CavalryCommands held Philippine Constabulary

5th U.S. Cavalry

10th U.S. CavalryBattles/wars Indian Wars Awards Medal of Honor ColonelCornelius Cole Smith (April 7, 1869 – January 10, 1936) was an American officer in the U.S. Army who served with the 6th U.S. Cavalry during the Sioux Wars. On January 1, 1891, he and four other cavalry troopers successfully defended a U.S. Army supply train from a force of 300 Sioux warriors at the White River in South Dakota, for which he received the Medal of Honor. He was the last man to receive the award in battle against the Sioux, and in a major Indian war.

In his later career, Smith served as an officer during the Spanish–American War and the subsequent Philippine Insurrection under Generals Leonard Wood and John J. Pershing. In 1910, he was appointed by Pershing as commander of the Philippine Constabularyand served at Fort Huachuca as commanding officer of Troop G, 5th U.S. Cavalry from 1912 to 1914. It was in this capacity that he accepted the surrender of Colonel Emilio Kosterlitzky, commander of Mexican federal forces at Sonora, on March 13, 1913. In 1918, he was appointed commander of Huachuca and the 10th U.S. Cavalry. Prior to his retirement, he also oversaw the construction of Camp Owen Beirne, adjacent to Fort Bliss, which served as the model for similar camps built following the end of World War I.

Smith’s son, Cornelius Cole Smith, Jr., who also served as a colonel in the Philippines during World War II,[1] was a successful author, historian and illustrator who wrote several books on the Southwestern United States including his biography entitled “Don’t Settle for Second: Life and Times of Cornelius C. Smith” (1977).Contents

[hide]

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Cornelius Cole Smith was born on April 7, 1869, in the frontier town of Tucson in the Arizona Territory. his father, Gilbert Cole Smith, was a member of a distinguished military family dating back to the Revolutionary War.[1] He had served as officer in the Union Army‘s famed California Column during the American Civil War and later became quartermaster at Fort Lowell in Tucson.[2][3] He was also related to brothers William and Granville H. Oury. His family lived at several outposts in the Arizona and New Mexico Territories, wherever his father happened to be stationed. In December 1882, they finally settled at Vancouver Barracks in the Washington Territory. Smith was then[when?] sent back east to Louisiana, Missouri, and in 1884 to Baltimore, Maryland. In 1888, Smith moved to Helena, Montana and joined the Montana National Guard on May 22, 1889.[4][5]

Smith poses with his favorite horse “Blue” in front of his quarters at Fort Wingate in 1895.

Smith poses with his favorite horse “Blue” in front of his quarters at Fort Wingate in 1895.On April 9, 1890, at age 21, Smith enlisted in the United States Army in Helena and was immediately sent out with 6th U.S. Cavalry Regiment for frontier duty in the Dakota Territory.[2][3][6][7][8][9][10][11]

Battle at White River, 1891[edit]

Within a year, Smith reached the rank of corporal and saw his first action during the Pine Ridge Campaign. On January 1, 1891, two days after the Battle at Wounded Knee Creek, he accompanied a fifty-three man escort of a U.S. Army supply train to the regiment’s camp at the battle site. While preparing to cross the White River, partially ice-covered during the winter, the supply train was suddenly attacked by a group of approximately 300 Sioux braves. In an attempt to save the wagon train, he and Sergeant Frederick Myers chose advanced positions from a knoll 300 yards from the river and held back the initial Sioux assault with four other troopers successfully defended their position against repeated enemy attacks.[12] After they had withdrawn, Smith and the others chased after the war party for a considerable distance before breaking off their pursuit.[4][6][9][10][11]

Smith’s actions at White River prevented the Sioux from capturing the supply wagons. He was cited for distinguished bravery in the face of a numerically superior enemy force and received the Medal of Honor[4][6][7][8][12] on February 4, 1891.[9][11]Service in Cuba and the Philippines, 1892-1912[edit]

The following year, on November 19, 1892, Smith was made a commissioned officer as a second lieutenant with the 2nd U.S. Cavalry. In 1898, he fought in Cuba during the Spanish–American War and in the Philippines during the Filipinoand Moro Rebellions under Generals Leonard Wood and John J. Pershingrespectively.

From 1903 to 1906, he served as captain with the 14th U.S. Cavalry,[13] in Mindanao under General Wood, during which time he helped publish A Grammar of the Maguindanao Tongue According to the Manner of Speaking It in the Interior and on the South Coast of the Island of Mindanao (1906) with Spanish Jesuit Rev. Father Jacinto Juanmart.

In 1908, he accepted a two-year position as superintendent of California‘s Sequoia National Park and Grant National Parks. In 1910, he returned to the Philippine Islands for 2 years [4] as commander of the Philippine Constabularyunder General Pershing.[2][3]Fort Huachuca and World War I, 1912-1920[edit]

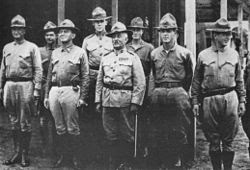

Smith (far right) as commander of the Philippine Constabulary with Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing and Moro chieftains in 1910. Smith participated in expeditions against the Moro rebels for much of his time in the Philippines.

Smith (far right) as commander of the Philippine Constabulary with Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing and Moro chieftains in 1910. Smith participated in expeditions against the Moro rebels for much of his time in the Philippines.After a nine-year tour of duty in the Philippines, Smith was brought back to the U.S. in 1912 and in fall transferred to the 4th U.S. Cavalry Regiment at Fort Huachuca in his home state of Arizona.[13] From December 1912 to December 1914 he was reassigned to the 5th U.S. Cavalry as commanding officer of its Troop G at Huachuca, when the 4th U.S. Cavalry was sent for rotation to Hawaii. On March 13, 1913, he formally accepted the surrender of Colonel Emilio Kosterlitzky, commander of Mexican federal forces of Sonora and his 209 followers in Nogales, Arizona after General Álvaro Obregón had defeated him days earlier.[2][3][4] The surrender was conducted in a formal ceremony, with Kosterlitzky presenting Smith his sword. The two officers later became lifelong friends.[14]

During 1915, Smith was a military attaché in Bogota and Caracas, and rose through the ranks from major to colonel of cavalry within the next two years.[2][3][4][13] He trained several regiments during World War I, but was denied further promotion and a field command in Europe due to the feud between General Pershing, then commander-in-chief of the American Expeditionary Forces on the Western Front (World War I), and Army Chief-of-StaffPeyton March. In 1918, he returned to Fort Huachuca where he assumed command of the post and the 10th U.S. Cavalry Regiment. His last assignment was at Fort Bliss where he had Camp Owen Beirne built, the model for similar bases constructed for servicemen following World War I. He retired in 1920 at the rank of colonel.[2][3]Retirement and later years 1920-36[edit]

Smith taught military science and tactics at the University of Arizona after leaving the U.S. Army and was later hired as a technical advisor for war films in Hollywood. In 1928, he became a member of the American Electoral Committee which oversaw the presidential elections in Nicaragua.[2] That same year, he was also a contributing editor for Alice Baldwin’s biography on her late husband Major General Frank Baldwin, Memoirs of the late Frank D. Baldwin, Major General, U.S.A., in which Smith related his experiences with Baldwin during the Spanish–American War. He went on to become a prolific author of articles relating to the American frontier in the Southwestern United States.[4]

Smith died in Riverside, California on January 10, 1936, at the age of 66.[4][11] He is buried at Evergreen Memorial Park and Mausoleum,[15][16] along with 1,000 other veterans.[17]Personal life[edit]

Smith was married; His son Cornelius Cole Smith Jr. was born 1913 at Fort Huachuca.

Grave site restoration[edit]

In November 2003, a special ceremony was held at Smith’s grave site to display a new 18-foot-tall flagpole and stone bench nearby. Smith’s son, Cornelius Cole Smith, Jr., was in attendance. Initially started by 16-year-old Michael Emett for an Eagle Scout project, this was the first of a planned restoration campaign for the graves of Riverside’s military veterans and town founders. The story was covered by The Press-Enterprise and encouraged community leaders to raise money for an endowment to provide for the upkeep of older rundown areas of the cemetery that are not watered or maintained.[18]A few years before, the California Department of Consumer Affairs ordered that sprinklers in the historic section be shut off because it lacked an endowment to pay for the water.[17][19]

Medal of Honor citation[edit]

Rank and organization: Corporal, Company K, 6th U.S. Cavalry. Place and date: Near White River, S. Dak., 1 January 1891. Entered service at: Helena, Mont. Birth: Tucson, Ariz. Date of issue: 4 February 1891.

Citation:With 4 men of his troop drove off a superior force of the enemy and held his position against their repeated efforts to recapture it, and subsequently pursued them a great distance.[20]

Emilio Kosterlitzky

Emilio Kosterlitzky Nickname(s) Eagle of Sonora

Mexican CossackBorn November 16, 1853

Moscow, RussiaDied March 2, 1928

Los Angeles, CaliforniaBuried Calvary Cemetery Allegiance Mexico

Service/branch Mexican Army

Years of service 1871 – 1914 Rank Colonel Battles/wars Mexican Apache Wars

Yaqui Wars

Mexican RevolutionOther work Spy Emilio Kosterlitzky (1853–1928) was a Russian-born polyglotlinguist and soldier of fortune who eventually became a spy for the United States.

Contents

[hide]

Biography[edit]

Emil Kosterlitzky was born on November 16, 1853 in Moscow, to a German mother and Russian Cossack father. He was noted for his language ability; he spoke English, French, Spanish, German, Russian, Italian, Polish, Danish and Swedish.

In his teens, Emil joined the Russian Navy as a midshipman. By 1871, at the age of 18, he deserted his ship in Venezuela. Kosterlitzky then traveled to the Mexican state of Sonora, where he changed his name to Emilio and joined the Mexican Army. During the 1880s he fought in the Mexican Apache Wars. He also assisted American troops pursuing Apachesacross the border under the 1882 United States–Mexico reciprocal border crossing treaty. Kosterlitzky became known to the American troops, who called him the “Mexican Cossack“. In 1885, Kosterlitzky was appointed commander of the Gendarmería Fiscal, the customs guard for the Mexican government, by President Porfirio Díaz.[1]

In 1913, Kosterlitzky was captured in Nogales, Sonora, by revolutionaries during the Mexican Revolution. He was jailed until 1914, when he, his wife, Francesca, and two daughters moved to Los Angeles, California, in the United States, where he became a translator for the U.S. Postal Service. During World War I, he pretended to be a German physician. He returned to Mexico in 1927, to investigate a plot against the government of the state of Baja California.

Kosterlitzky died in Los Angeles on March 2, 1928, and is buried in Calvary Cemetery in East Los Angeles.

Smedley Butler

Smedley Butler Birth name Smedley Darlington Butler Nickname(s) “Old Gimlet Eye”, “The Fighting Quaker”, “Old Duckboard” Born July 30, 1881

West Chester, Pennsylvania, U.S.Died June 21, 1940 (aged 58)

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.Buried Oaklands Cemetery

West Chester, Pennsylvania, U.S.Allegiance United States of America

Service/branch United States Marine Corps

Years of service 1898–1931 Rank Major general

Unit 2nd Marine Regiment

1st Marine RegimentCommands held 13th Marine Regiment

Marine Expeditionary Force, China

1st Marine RegimentBattles/wars Spanish–American War

Philippine–American War

- Battle of Tientsin

- Battle of San Tan Pating

- Battle of Masaya

- Siege of Granada, Nicaragua

- Battle of Coyotepe Hill

- Infiltration of Mexico City

- Battle of Fort Dipitie

- Battle of Fort Rivière

Awards Medal of Honor (2)

Marine Corps Brevet Medal

Order of the Black Star(commandeur)

Haitian Médaille militaireOther work Coal miner, author, public speaker, Philadelphia Director of Public Safety (1924–1925) Smedley Darlington Butler (July 30, 1881 – June 21, 1940) was a United States Marine Corpsmajor general, the highest rank authorized at that time, and at the time of his death the most decorated Marine in U.S. history. During his 34-year career as a Marine, he participated in military actions in the Philippines, China, in Central America and the Caribbean during the Banana Wars, and France in World War I. Butler is well known for having later become an outspoken critic of U.S. wars and their consequences, as well as exposing the Business Plot, an alleged plan to overthrow the U.S. government.

By the end of his career, Butler had received 16 medals, five for heroism. He is one of 19 men to receive the Medal of Honor twice, one of three to be awarded both the Marine Corps Brevet Medal and the Medal of Honor, and the only Marine to be awarded the Brevet Medal and two Medals of Honor, all for separate actions.

In 1933, he became involved in a controversy known as the Business Plot, when he told a congressional committee that a group of wealthy industrialists were planning a military coup to overthrow Franklin D. Roosevelt, with Butler selected to lead a march of veterans to become dictator, similar to other Fascist regimes at that time. The individuals involved all denied the existence of a plot and the media ridiculed the allegations. A final report by a special House of Representatives Committee confirmed some of Butler’s testimony.

In 1935, Butler wrote a book titled War Is a Racket, where he described and criticized the workings of the United States in its foreign actions and wars, such as those he was a part of, including the American corporations and other imperialist motivations behind them. After retiring from service, he became a popular activist, speaking at meetings organized by veterans, pacifists, and church groups in the 1930s.Contents

[hide]

Early life[edit]

Smedley Butler was born July 30, 1881, in West Chester, Pennsylvania, the eldest of three sons. His parents, Thomas and Maud (née Darlington) Butler,[1] were descended from local Quaker families. Both of his parents were of entirely English ancestry, all of whom had been in what is now the United States since the 1600s.[2] His father was a lawyer, a judge and, for 31 years, a congressman and chair of the House Naval Affairs Committee during the Harding and Coolidgeadministrations. His maternal grandfather was Smedley Darlington, a Republican congressman from 1887 to 1891.[3]

Butler attended the West Chester Friends Graded High School, followed by The Haverford School, a secondary school popular with sons of upper-class Philadelphia families.[4] A Haverford athlete, he became captain of its baseball team and quarterback of its football team.[1] Against the wishes of his father, he left school 38 days before his seventeenth birthday to enlist in the Marine Corps during the Spanish–American War. Nevertheless, Haverford awarded him his high school diploma on June 6, 1898, before the end of his final year. His transcript stated that he completed the scientific course “with Credit”.[1]Military career[edit]

Spanish–American War[edit]

In the Spanish war fervor of 1898, Butler lied about his age to receive a direct commission as a Marine second lieutenant.[1] He trained in Washington D.C. at the Marine Barracks on the corner of 8th and I Streets SE. In July 1898, he went to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, arriving shortly after its invasion and capture.[5] His company soon returned to the U.S. and after a short break, he was assigned to the armored cruiser USS New York for four months.[6] He came home to be mustered out of service in February 1899,[6] but on 8 April 1899, he accepted a commission as a first lieutenant in the Marine Corps.[6]

Philippine–American War[edit]

The Marine Corps sent him to Manila, Philippines.[7] On garrison duty with little to do, Butler turned to alcohol to relieve the boredom. He once became drunk and was temporarily relieved of command after an unspecified incident in his room.[8]

In October 1899, he saw his first combat action when he led 300 Marines to take the town of Noveleta, from Filipino rebels known as Insurrectos. In the initial moments of the assault, his first sergeant was wounded. Butler briefly panicked, but quickly regained his composure and led his Marines in pursuit of the fleeing enemy.[8] By noon the Marines had dispersed the rebels and taken the town. One Marine had been killed and ten were wounded. Another 50 Marines had been incapacitated by the humid tropical heat.[9]

After the excitement of this combat, garrison duty again became routine. Butler had a very large Eagle, Globe, and Anchortattoo made which started at his throat and extended to his waist. He also met Littleton Waller, a fellow Marine with whom he maintained a lifelong friendship. When Waller received command of a company in Guam, he was allowed to select five officers to take with him. He chose Butler. Before they had departed, their orders were changed and they were sent to China aboard the USS Solace to help put down the Boxer Rebellion.[9]Boxer Rebellion[edit]

Once in China, Butler was initially deployed at Tientsin. He took part in the Battle of Tientsin on July 13, 1900 and in the subsequent Gaselee Expedition, during which he saw the mutilated remains of Japanese soldiers. When he saw another Marine officer fall wounded, he climbed out of a trench to rescue him. Butler was then himself shot in the thigh. Another Marine helped him get to safety, but also was shot. Despite his leg wound, Butler assisted the wounded officer to the rear. Four enlisted men would receive the Medal of Honor in the battle. Butler’s commanding officer, Major Littleton W. T. Waller, personally commended him and wrote that “for such reward as you may deem proper the following officers: Lieutenant Smedley D. Butler, for the admirable control of his men in all the fights of the week, for saving a wounded man at the risk of his own life, and under a very severe fire.” Commissioned officers were not then eligible to receive the Medal of Honor, and Butler instead received a promotion to captain by brevet while he recovered in the hospital, two weeks before his nineteenth birthday.

He was eligible for the Marine Corps Brevet Medal when it was created in 1921, and was one of only 20 Marines to receive it.[10] His citation reads:The Secretary of the Navy takes pleasure in transmitting to First Lieutenant Smedley Darlington Butler, United States Marine Corps, the Brevet Medal which is awarded in accordance with Marine Corps Order No. 26 (1921), for distinguished conduct and public service in the presence of the enemy while serving with the Second Battalion of Marines, near Tientsin, China, on 13 July 1900. On 28 March 1901, First Lieutenant Butler is appointed Captain by brevet, to take rank from 13 July 1900.[11]

The Banana Wars[edit]

Butler participated in a series of occupations, police actions, and interventions by the United States in Central America and the Caribbean, commonly called the Banana Wars because their goal was to protect American commercial interests in the region, particularly those of the United Fruit Company. This company had significant financial stakes in the production of bananas, tobacco, sugar cane, and other products throughout the Caribbean, Central America and the northern portions of South America. The U.S. was also trying to advance its own political interests by maintaining its influence in the region and especially its control of the Panama Canal. These interventions started with the Spanish–American War in 1898 and ended with the withdrawal of troops from Haiti and President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy in 1934.[12]After his retirement, Butler became an outspoken critic of the business interests in the Caribbean, criticizing the ways in which U.S. businesses and Wall Street bankers imposed their agenda on United States foreign policy during this period.[13]

Honduras[edit]

In 1903, Butler was stationed in Puerto Rico on Culebra Island. Hearing rumors of a Honduran revolt, the United States government ordered his unit and a supporting naval detachment to sail to Honduras, 1,500 miles (2,414 km) to the west, to defend the U.S. Consulate in Honduras. Using a converted banana boat renamed the Panther, Butler and several hundred Marines landed at the port town of Puerto Cortés. In a letter home, he described the action: they were “prepared to land and shoot everybody and everything that was breaking the peace”,[14] but instead found a quiet town. The Marines re-boarded the Panther and continued up the coast line looking for rebels at several towns, but found none.

When they arrived at Trujillo, however, they heard gunfire, and came upon a battle in progress that had been waged for 55 hours between rebels called Bonillista and Honduran government soldiers at a local fort. At the sight of the Marines, the fighting ceased and Butler led a detachment of Marines to the American consulate, where he found the consul, wrapped in an American flag, hiding among the floor beams. As soon as the Marines left the area with the shaken consul, the battle resumed and the Bonillistas soon controlled the government.[14] During this expedition Butler earned the first of his nicknames, “Old Gimlet Eye”. It was attributed to his feverish, bloodshot eyes—he was suffering from some unnamed tropic fever at the time—which enhanced his penetrating and bellicose stare.[15]Marriage and business[edit]

After the Honduran campaign, Butler returned to Philadelphia. He married Ethel Conway Peters of Philadelphia in Bay Head, New Jersey, on June 30, 1905.[16] His best man at the wedding was his former commanding officer in China, Lieutenant Colonel Littleton Waller.[17] The couple eventually had three children: a daughter, Ethel Peters Butler (Mrs. John Wehle), and two sons, Smedley Darlington, Jr., and Thomas Richard.[18]

Butler was next assigned to garrison duty in the Philippines, where he once launched a resupply mission across the stormy waters of Subic Bay after his isolated outpost ran out of rations. In 1908, he was diagnosed as having a nervous breakdown and received nine months sick leave which he spent at home. He successfully managed a coal mine in West Virginia, but returned to active duty in the Marine Corps at the first opportunity.[19]Central America[edit]

From 1909 to 1912, Butler served in Nicaragua enforcing U.S. policy. With a 104 degree fever, led his battalion to the relief of a rebel-besieged city, Granada. In December 1909, he commanded the 3d Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, on the Isthmus of Panama. On August 11, 1912, he was temporarily detached to command an expeditionary battalion he led in the Battle of Masaya on September 19, 1912 and the bombardment, assault, and capture of Coyotepe Hill, Nicaragua in October 1912. He remained in Nicaragua until November 1912, when he rejoined the Marines of 3d Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, at Camp Elliott, Panama.[3]

Veracruz, Mexico, and first Medal of Honor[edit]

Marine Officers at Veracruz. Front row, left to right: Wendell C. Neville; John A. Lejeune; Littleton W. T. Waller, Commanding; Smedley Butler

Marine Officers at Veracruz. Front row, left to right: Wendell C. Neville; John A. Lejeune; Littleton W. T. Waller, Commanding; Smedley ButlerButler and his family were living in Panama in January 1914 when he was ordered to report as the Marine officer of a battleship squadron massing off the coast of Mexico, near Veracruz, to monitor a revolutionary movement. He did not like leaving his family and the home they had established in Panama and he intended to request orders home as soon as he determined he was not needed.[20]

On 1 March 1914, Butler and Navy Lieutenant (later Admiral) Frank J. Fletcher (not to be confused with his uncle, who was then rear admiral Frank F. Fletcher) “went ashore at Veracruz, where they met the American superintendent of the Inter-Oceanic Railway and surreptitiously rode in his private car [a railway car] up the line seventy-five miles to Jalapa and back”.[21] A purpose of the trip was to allow Butler and Fletcher to discuss the details of a future expedition into Mexico. Fletcher’s plan required Butler to make his way into the country and develop a more detailed invasion plan while inside its borders. It was a spy mission and Butler was enthusiastic to get started. When Admiral Fletcher explained the plan to the commanders in Washington, D.C., they agreed to it. Butler was given the go-ahead.

A few days later, Butler set out by train on his spy mission to Mexico City, with a stop over at Puebla. He made his way to the U.S. Consulate in Mexico City, posing as a railroad official named “Mr. Johnson”.

- March 5th. As I was reading last night, waiting for dinner to be served, a visitant, rather than a visitor, appeared in my drawing-room incognito – a simple “Mr. Johnson,” eager, intrepid, dynamic, efficient, unshaven! * * * [22]

He and the chief railroad inspector scoured the city, saying they were searching for a lost railroad employee; there was no lost employee, and in fact the employee they said was lost never existed. The ruse gave Butler access to various areas of the city. In the process of the so-called search, they located weapons in use by the Mexican army, and determined the sizes of units and states of readiness. They updated maps and verified the railroad lines for use in an impending US invasion.[23]

On March 7, 1914, he returned to Veracruz with the information he had gathered and presented it to his commanders. The invasion plan was eventually scrapped when authorities loyal to Victoriano Huerta detained a small American naval landing party (that had gone ashore to buy gasoline) in Tampico, Mexico, which led to what became known as the Tampico Affair.[24]