Ditto

The reality of the Model 40 genre, including this latest version, the Model 40-1, remains a specialty or niche handgun, which has never outsold the more-traditional S&W J-frame versions. This is not to say the M40 genre is not optimum for its purpose, which is up-close personal self-defense against two-legged predators. The problem is that a DAO small-frame revolver is simply more difficult to shoot well and retaining this ability requires at the least episodic practice.

The reality of the Model 40 genre, including this latest version, the Model 40-1, remains a specialty or niche handgun, which has never outsold the more-traditional S&W J-frame versions. This is not to say the M40 genre is not optimum for its purpose, which is up-close personal self-defense against two-legged predators. The problem is that a DAO small-frame revolver is simply more difficult to shoot well and retaining this ability requires at the least episodic practice.

The more traditional double-action/single-action J-frame allows for thumb cocking the hammer so that you get a 3- to 5-pound, short-moving trigger, which makes getting hits a lot easier compared to cranking back on a 12-pound DA trigger with long movement.

The Model 40 in its various incarnations allows no room for rationalization of user ability or denial of the gun’s singular purpose—self-defense. You must decide to either practice and gain the skill necessary to shoot it well or resign yourself to only muzzle-contact use.

This sample Model 40-1, like all J-frame S&Ws, has the inherent accuracy, which exceeds what most folks can deliver from any of them. Shooting from a rest with good trigger control and sight alignment, a J-frame’s accuracy is the equal of any S&W revolver. Doing this is easier said than done, however.

The reality of real-world use, by shooting DA in response to an attack, falls far behind a shooter’s feeling of accomplishment and self-worth when his range practice firing DA results in seriously-missed targets save for those large sheets of paper shot at arm’s length distance. Even for those who accept the reality of DA shooting for self-defense, doing so with such a small-sized gun results in truly having a gun that’s carried much but shot very little. Indeed, it’s usually carried with the thought that, “I’ll be able to do it if and when I have to.” (“It” being successfully engaging a threat under the worst conditions.)

Okay, if we accept the above, why then do any number of us continue to buy and carry the M40 or its various permutations? Simple. Because it is the best tool for the job when social and legal constraints preclude using a larger arm.

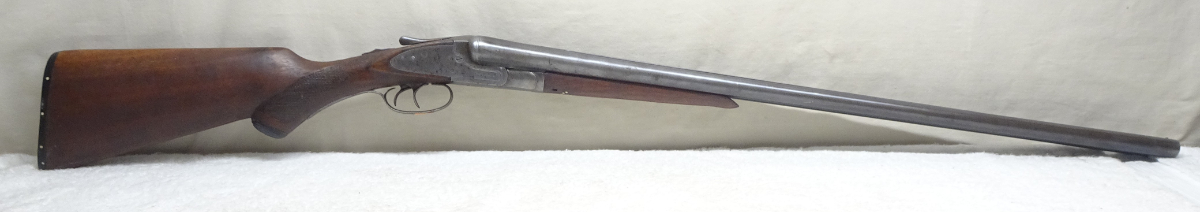

Gun Details

Let’s take a close look at the Model 40-1. It has a manual safety that operates in the same manner as this part on a semi-autopistol. To fire the M40, a firm grip is required to disengage the grip safety. This forces the user to properly grip the gun, which is one of the basic steps in firing a well-placed shot. The grip safety also provides some impediment to accidentally pulling the trigger.

Another advantage is the shape of the grip safety; it sticks out of the backstrap even when depressed and is vertically grooved, the combination of which gives me a better, more secure shooting grip. One wonders why S&W doesn’t groove all the backstraps of their small-frame revolvers, or why this is not requested more from gunsmiths.

Historical legend has it that Horace Wesson devised the grip safety on the original .38 Safety Hammerless model so that a small child could not fire the revolver, due to their hand size being too small to both depress the grip safety and pull the trigger. He supposedly tested the design by having his young nephew attempt and fail to fire the so-constructed gun.

In the first modern versions, this grip safety could be neutralized, thanks to a supplied pin found under the grip panels. The pin was then inserted into matching holes in a depressed grip safety on the frame. Unfortunately, this feature is not provided with the new M40-1 since, thanks in no small part to US civil liability laws, S&W would be sued for providing a means to defeat this grip safety device.

The other obvious advantage of a hammerless revolver is there’s no hammer spur to catch on clothing when carried in a pocket. What is not so readily apparent is that lacking an exposed hammer, you can grip the gun slightly higher for more recoil control since the hammer can’t hit the web of your hand. As a matter of fact, the original 1952-issued Centennial has higher grip panels than do the exposed-hammer guns. While a nice touch, this was not done with the new M40-1. The grip panels are nicely checkered and have a large “diamond” center surrounding the grip screw holes. These grips are much nicer than those that came with my own Model 40s and 42s, which are smooth-faced and rather coarse-grained.

Moving up top, the M40-1 has two improvements. First, the sights are wider and much easier to see, particularly as I’ve gotten older. The front sight is ramped and grooved, and the rear is a square notch in the top strap. The trigger is smooth faced and slightly rounded, and the cylinder release checkered and dished out for easy operation.

Secondly, the barrel is stamped (on its left side) “.38 S&W SPL. +P,” which might be of some comfort to those who are concerned that shooting lots of such loads will ruin their gun. My personal thought on this is to shoot what you want and if and when you manage to wear the gun out, get another one! I regularly carry and shoot CCI Gold Dot 135-grain +P (which is expressly made for snub-nose revolvers), CorBon 110-grain +P or Hornady 125-grain non-+P JHP loads in my circa-1973 Models 40 and 42. Neither has “worn out” yet despite my best efforts, but I have two more new-in-the-box that I bought back then “just in case.”

Shooting Impressions

Speaking of shooting, the M40 genre has always had an action that differs from the DA movement of the exposed-hammer J-frames. I find the trigger action to be longer in its rearward movement and as it moves, the cylinder indexes well before the hammer completes its rearward movement and releases. I do not have an explanation for this and I’ve asked some of the S&W folks, who said the actions are the same. Be this as it may, I can shoot the M40 better than I do the exposed-hammer guns.

This longer action also lends itself well to a two-stage DA trigger pull. To do this, I grip the gun such that my trigger finger hits the frame just as the cylinder is indexed and before the hammer is released. I then slide my trigger finger rearward while catching part of my finger between the trigger and frame, in effect squeezing my finger out of the way with rearward pressure. This effectively gives me a sort of a long SA trigger press with much better accuracy. This is how I shot a 2.25-inch group at 18 yards. Arguably, this is more “trick” than practical, but having mastered this I have increased my ability to get good hits at otherwise prohibitive distances.

Conversely, for defensive shooting the best method is pulling the trigger with steadily increasing pressure until the shot breaks and then riding the trigger forward at the same speed until the action resets. This metronome motion of back and forth at a constant speed I’ve found to be the path to fast, accurate shooting, for this practiced motion carries over when pressing the trigger quite quickly with less overall gun movement.

This then also brings up the notion of having a so-called “action job” done on your J-frame revolver. In my opinion not only is this a waste of money, it also degrades the gun’s reliability. The only way to get a lighter trigger pull is to cut springs and polish parts. As noted above, and verified by world-champion revolver speed shooter Jerry Miculek, you can only shoot a revolver as fast as the trigger resets. He runs factory springs in all his guns.

The J-frame M40-1 uses a coil mainspring, which does not lend itself to weakening without increasing misfires. Simply put, the small-frame revolvers are hard to shoot well and any money spent should be for more ammo. The only “trick” to shooting one well is lots and lots of ongoing practice.

Final Notes

Hammerless J-frames can be addicting. In fact, I doubt that you can get by with owning just one. And for self-defense, carrying two of them is still the quickest reload. Fortunately, with the new Model 40-1 you can have the gun finished all blue or color casehardened or nickel. Of course, then you’ll want to have a .22 LR version and perhaps a pair of Crimson Trace Lasergrips as well!

For more information contact: Smith & Wesson, 2100 Roosevelt Ave, Dept CH, Springfield, MA 01104; 800-331-0852; www.smith-wesson.com.