A priest, a minister and a guru sat discussing the best positions for prayer, while a telephone repairman worked nearby

The Martini Rifle

When the British Empire was at its height and most powerful. This Rifle was the solid backbone of the Empire. Especially when as Kipling said so well. “The Natives are restless and the Regiment Marches”.

Now I have a couple of these relics from the past in ye old gun safe. So here is what I have found out about these guns.

In that they are a very simple, strong and well thought out piece of weaponry. All of which are what most soldiers want. As I have found out myself. That in the field. The Easy becomes very hard to do. The difficult is almost always impossible.

That & one can never underestimate the ways a soldier can mess up his gear in the blink of a Hooker eye. Just ask any Veteran and they will have a lot of stories on this subject.

Moving right along smartly now. I also found out that while it shoots a huge round the .577/450 Boxer-Henry.

Compare it to a 22 Long Rifle Round!

One also has to remember that it is a black powder round. Which is a good thing. As it will give the shooter of it. A big shove for recoil unlike smokeless powder, Which is like getting hit with a baseball bat.

The other good news about this round. Is that it is fairly accurate out to around 200 yards or so. That & when it hits somebody with that soft lead bullet. I am willing to be that they will not be getting up soon afterwards.

Now here is some more information about this stout rifle of the Queen!

Martini–Henry

| Martini–Henry Mk I–IV | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Type | Service rifle Shotgun (Greener Prison Variant) |

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1871–1918 |

| Used by | United Kingdom & Colonies, Afghanistan, Ottoman Empire, Romania |

| Wars | British colonial wars Second Anglo-Afghan War Herzegovina Uprising (1875–1878) Russo-Turkish War War of the Pacific Anglo-Zulu War Greco-Turkish War (1897) First Boer War Balkan Wars World War I Greco-Turkish War (1919–22) |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Friedrich von Martini |

| Designed | 1870 |

| Manufacturer | Various |

| Produced | 1871–1889 |

| No. built | approx. 500,000–1,000,000 |

| Variants | Martini–Henry Carbine Greener Prison Shotgun Gahendra rifle |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | 8 pounds 7 ounces (3.827 kg) (unloaded), 9 pounds, 4.75 ounces (with sword bayonet) |

| Length | 49 inches (124.5 cm) |

|

|

|

| Cartridge | .577/450 Boxer-Henry .577/450 Martini–Henry .303 British 11.43x55R (Ottoman) 11.43x59R (Romanian) 7.65×53 (Ottoman) |

| Calibre | 0.450 in (11.4 mm) |

| Action | Martini Falling Block |

| Rate of fire | 12 rounds/minute |

| Muzzle velocity | 1,300 ft/s (400 m/s)[1] |

| Effective firing range | 400 yd (370 m) |

| Maximum firing range | 1,900 yd (1,700 m) |

| Feed system | Single shot |

| Sights | Sliding ramp rear sights, Fixed-post front sights |

(From Left to Right): A .577 Snidercartridge, a Zulu War-era rolled brass foil .577/450 Martini–Henry Cartridge, a later drawn brass .577/450 Martini–Henry cartridge, and a .303 British Mk VII SAA Ball cartridge

The Martini–Henry was a breech-loading single-shot lever-actuated rifle used by the British Army. It first entered service in 1871, eventually replacing the Snider–Enfield, a muzzle-loader converted to the cartridge system. Martini–Henry variants were used throughout the British Empire for 30 years. It combined the dropping-block action first developed by Henry O. Peabody (in his Peabody rifle) and improved by the Swiss designer Friedrich von Martini, combined with the polygonal barrel rifling designed by Scotsman Alexander Henry.

Though the Snider was the first breechloader firing a metallic cartridge in regular British service, the Martini was designed from the outset as a breechloader and was both faster firing and had a longer range.[1]

There were four main marks of the Martini–Henry rifle produced: Mark I (released in June 1871), Mark II, Mark III, and Mark IV. There was also an 1877 carbine version with variations that included a Garrison Artillery Carbine, an Artillery Carbine (Mark I, Mark II, and Mark III), and smaller versions designed as training rifles for military cadets. The Mark IV Martini–Henry rifle ended production in the year 1889, but remained in service throughout the British Empire until the end of the First World War. It was seen in use by some Afghantribesmen as late as the Soviet invasion.

Early in 2010 and 2011, United States Marines recovered at least three from various Taliban weapons caches in Marjah.[2]

In April 2011, another Martini–Henry rifle was found near Orgun in Paktika Province by United States Army’s 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault).

The Martini–Henry was copied on a large scale by North-West Frontier Province gunsmiths. Their weapons were of a poorer quality than those made by Royal Small Arms Factory, Enfield, but accurately copied down to the proof markings. The chief manufacturers were the Adam Khel Afridi, who lived around the Khyber Pass. The British called such weapons “Pass-made rifles“.

Contents

[hide]

Overview[edit]

In the original chambering, the rifles fired a round-nosed, tapered-head .452-inch, soft hollow-based lead bullet, wrapped in a paper patch giving a wider diameter of .460 to .469-inch; it weighed 485 grains.[1] It was crimped in place with two cannelures (grooves on the outside neck of the case), ahead of 2 fibre card or mill board disks, a concave beeswax wad, another card disk and cotton wool filler. This sat on top of the main powder charge inside initially a rimmed brass foil cartridge, later made in drawn brass.

The cartridge case was paper lined so as to prevent the chemical reaction between the black powder and the brass. Known today as the .577/450, a bottle-neck design with the same base as the .577 cartridge of the Snider–Enfield. It was charged with 85 grains (5.51 g) of Curtis and Harvey’s No.6 coarse black powder,[1] notorious for its heavy recoil.[3] The cartridge case was ejected to the rear when the lever was operated.

The rifle was 49 inches (124.5 cm) long, the steel barrel 33.22 inches (84 cm). The Henry patent rifling produced a heptagonal barrel with seven grooves with one turn in 22 inches (560 mm). The weapon weighed 8 pounds 7 ounces (3.83 kg). A sword bayonet was standard issue for noncommissioned officers; when fitted, the weapon extended to 68 inches (172.7 cm) and weight increased to 10 pounds 4 ounces (4.65 kg).

The standard bayonet was a socket-type spike, either converted from the older Pattern 1853 (overall length 20.4 inches) or newly produced as the Pattern 1876 (overall length 25 inches), referred to as the “lunger”.[3] A bayonet designed by Lord Elcho was intended for chopping and other sundry non-combat duties, and featured a double row of teeth so it could be used as a saw; it was not produced in great numbers and was not standard issue.

The Mk2 Martini–Henry rifle, as used in the Zulu Wars, was sighted to 1,800 yards. At 1,200 yards (1100 m), 20 shots exhibited a mean deflection from the centre of the group of 27 inches (69.5 cm), the highest point on the trajectory was 8 feet (2.44 m) at 500 yards (450 m).

A 0.402 calibre model, the Enfield–Martini, incorporating several minor improvements such as a safety catch, was gradually phased in to replace the Martini–Henry from about 1884. The replacement was gradual, to use up existing stocks of the old ammunition.

However, before this was complete, the decision was made to replace the Martini–Henry rifles with the .303 calibre bolt-action magazine Lee–Metford, which gave a considerably higher maximum rate of fire. Consequently, to avoid having three different rifle calibres in service, the Enfield–Martinis were withdrawn, converted to 0.45 calibre, and renamed Martini–Henry Mk IV “A”, “B” and “C” pattern rifles. Some 0.303 calibre black-powder carbine versions were also produced, known as the Martini–Metford, and even 0.303 calibre cordite carbines, called Martini–Enfields (as opposed to Enfield–Martinis).

During the Martini–Henry’s service life the British army was involved in a large number of colonial wars, most notably the Anglo-Zulu War in 1879. The rifle was used in the Battle of Isandlwana, and by the company of the 2nd Battalion, 24th Regiment of Foot at the battle of Rorke’s Drift, where 139 British soldiers successfully defended themselves against several thousand Zulus. The weapon was not completely phased out until 1904.

The rifle suffered from cartridge-extraction problems during the Zulu War, mostly due to the thin, weak, pliable foil brass cartridges used: they expanded too much into the rifle’s chamber on detonation, to the point that they stuck or tore open inside the rifle’s chamber. It would eventually become difficult to move the breech block and reload the rifle, substantially diminishing its effectiveness, or rendering it useless if the block could not be opened. After investigating the matter, the British Army Ordnance Department determined the fragile construction of the rolled brass cartridge, and fouling due to the black-powder propellant, were the main causes of this problem.

To correct this, the weak rolled brass cartridge was replaced by a stronger drawn brass version, and a longer loading lever was incorporated into the MK-IV to apply greater torque to operate the mechanism when fouled.[1] These later variants were more reliable in battle, although it was not until smokeless nitro powders and copper-coated bullets were tried out in these rifles in the 1920s that accuracy and 100% reliability of cartridge case extraction was finally achieved by Birmingham ammunition makers (Kynoch). English hunters on various safaris, mainly in Africa, found the Martini using a cordite charge and a 500-grain full-metal-jacketed bullet effective in stopping large animals such as hippopotamus up to 80 yards away.

The nitro based/shotgun powders were used in Kynoch’s .577/450 drawn-brass Martini–Henry cartridge cases well into the 1960s for the commercial market, and again were found to be very reliable and, being smokeless, eliminated fouling issues. The powder’s burning with less pressure inside the cartridge case prevented the brass cases from sticking inside the rifle’s chamber (because they were not expanding as much as the original black-powder loads did).

The rifle remained a popular competition rifle at National Rifle Association meetings, at Bisley, Surrey, and (NRA) Civilian and Service Rifle matches from 1872–1904, where it was used up to 1,000 yards using the standard military service ammunition of the day. By the 1880s the .577/.450 Boxer Henry round was recognised by the NRA as a 900-yard cartridge, as shooting the Martini out to 1,000 yards or (3/4 of a mile) was difficult, and took great skill to assess the correct amount of windage to drop the 485 grain bullet on the target. But by 1904 more target shooters were using the new .303 cal cartridge, which was found to be much more accurate, and thus interest in the .577/450 fell away, to the point that by 1909 they were rarely used at Bisley matches, with shooters favouring the later Lee–Enfield bolt action magazine rifles.[4]

In 1879, however, it was generally found that in average hands the .577/450 Martini–Henry Mk2, although the most accurate of the Martinis in that calibre ever produced for service life, was really only capable of hitting a man-size target out to 400 yards. This was due to the bullet going subsonic after 300 yards and gradually losing speed thereafter, which in turn affected consistency and accuracy of the bullet in flight. The 415-grain Martini Carbine load introduced in 1878 shot better out to longer ranges and had less recoil when it was fired in the rifles, with its reduced charge of only 75 grains of Curtis & Harvey’s. It was found that, while the rifle with its 485 grain bullet shot point of aim to 100 yards, the carbine load when fired in the rifles shot 12 inches high at the same range, but then made up for this by shooting spot-on out to 500 yards.[5] These early lessons enabled tactics to be evolved to work around the limitations of this large, slow, and heavy calibre during the Zulu War. During most of the key battles, such as Rorke’s Drift and the battle of Ulundi, the order to volley fire was not given until the Zulus were at or within 400 yards.

The ballistic performance of a .577/450 is somewhat similar to that of a .45/70 American Government round, as used prolifically throughout the American Frontier West and by buffalo hunters, though the .577/450 has more power due to its extra 15 grains of black powder inside the cartridge case. It is clear from early medical field surgeons’ reports that at 200 yards the rifle really came into its own, and inflicted devastating and horrific wounds on the Zulus in the Anglo–Zulu War.[6] The MK2 Martini’s sights are marked to 1,800 yards, but this setting was only ever used for long-range mass volley firing to harass an artillery position or a known massed cavalry position, prior to a main fight, and to prevent or delay infantry attacks. A similar “drop volley sight” whereby the rifle’s bullets were dropped long range onto the target were employed on the later .303 Lee–Enfield rifles of WW1, which had a graduation lever sight calibrated up to 2,800 yards.

The Nepalese produced a close copy of the British Martini–Henry incorporating certain Westley Richards improvements to the trigger mechanism but otherwise very similar to the British Mark II. These rifles can be identified by their Nepalese markings and different receiver ring. A noticeably different variant incorporating earlier Westley Richards ideas for a flat-spring driven hammer within the receiver in lieu of the coil-spring powered striker of the von Martini design, known as the Gahendra rifle, was produced locally in Nepal.[7] While generally well-made, the rifles were produced substantially by hand, making the quality extremely variable. Though efforts were being made to phase out these rifles, presumably by the 1890s, some 9000 were still in service in 1906.[7]

The Martini–Henry saw service in World War I in a variety of roles, primarily as a Reserve Arm, but it was also issued (in the early stages of the war) to aircrew for attacking observation balloons with newly developed incendiary ammunition, and aircraft. Martini–Henrys were also used in the African and Middle Eastern theatres during World War I, in the hands of Native Auxiliary troops.

Greener shotgun[edit]

A shotgun variant known as the Greener Police Gun or the Greener Prison Shotgun was chambered in a special round that would make the weapon useless to anyone who stole it.[8] An example can be seen at the Royal Armouries Museumin Leeds.[9] Greener also used the Martini action for the GP single-barreled shotgun firing standard 12-bore ammunition, which was a staple for gamekeepers and rough shooters in Britain up to the 1960s.

Greener harpoon gun[edit]

W.W. Greener also used the Martini action to produce the Greener-Martini Light Harpoon Gun used for whaling, and also for commercial harvest of tuna and other large fish.[10] The gun fired a blank cartridge to propel the harpoon. A special barrel and stock were fitted to accommodate the harpoon and to lower weight. A Greener harpoon gun is used by Quint in the 1975 movie Jaws.[11]

Turkish, Romanian, and Boer Republics Peabody–Martini–Henry rifles[edit]

Unable to purchase Martini–Henry rifles from the British because their entire production was going to rearming British troops, Ottoman Turkey purchased weapons identical to the Mark I from the Providence Tool Company in Providence, Rhode Island, USA (the manufacturers of the somewhat similar Peabody rifle), and used them effectively against the Russians in the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878).[12][13] The Ottoman Turkish outlaw and folk hero Hekimoğlu famously used the rifle during his raids on landowners.[14] The rifle is referred to as Aynalı Martin in Turkey and features in several famous folk songs.

A now scarce variant of the Peabody–Martini–Henry built by Steyr was adopted by Romania in 1879. Significant numbers of the basic design, with variations, were also produced for the Boer Republics, both in Belgium and, via Westley Richards, in Birmingham, as late as the late 1890s.

Operation of the Martini action[edit]

The lock and breech are held to the stock by a metal bolt (A). The breech is closed by the block (B) which turns on the pin (C) that passes through the rear of the block. The end of the block is rounded to form a knuckle joint with the back of the case (D) which receives the force of the recoil rather than the pin (C).

Below the trigger-guard the lever (E) works a pin (F) which projects the tumbler (G) into the case. The tumbler moves within a notch (H) and acts upon the block, raising it into the firing position or allowing it to fall according to the position of the lever.

The block (B) is hollowed along its upper surface (I) to assist in inserting a cartridge into the firing chamber (J). To explode the cartridge the block is raised to position the firing mechanism (K) against the cartridge. The firing mechanism consists of a helical spring around a pointed metal striker, the tip of which passes through a hole in the face of the block to impact the percussion-cap of the inserted cartridge. As the lever (E) is moved forward the tumbler (G) revolves and one of its arms engages and draws back the spring until the tumbler is firmly locked in the notch (H) and the spring is held by the rest-piece (L) which is pushed into a bend in the lower part of the tumbler.

After firing, the cartridge is partially extracted by the lock. The extractor rotates on a pin (M) and has two vertical arms (N), which are pressed by the rim of the cartridge pushed home into two grooves in the sides of the barrel. A bent arm (O), forming an 80° angle with the extractor arms, is forced down by the dropping block when the lever is pushed forward, so causing the upright arms to extract the cartridge case slightly and allow easier manual full extraction.

As well as British service rifles, the Martini breech action was applied to shotguns by the Greener company of Britain, whose single-shot “EP” riot guns were still in service in the 1970s in former British colonies. The Greener “GP” shotgun, also using the Martini action, was a favourite rough-shooting gun in the mid-20th century. The martini action was used by BSA and latterly BSA/Parker Hale for their series of “Small Action Martini” small bore target rifles that were in production until 1955.

Comparison with contemporary rifles[edit]

| Calibre | System | Country | Velocity | Height of trajectory | Ammunition | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muzzle | 500 yd (460 m) | 1,000 yd (910 m) | 1,500 yd (1,400 m) | 2,000 yd (1,800 m) | 500 yd (460 m) | 1,000 yd (910 m) | 1,500 yd (1,400 m) | 2,000 yd (1,800 m) | Propellant | Bullet | |||

| .433 in (11.0 mm) | Werndl–Holub rifle | Austria-Hungary | 1,439 ft/s (439 m/s) | 854 ft/s (260 m/s) | 620 ft/s (190 m/s) | 449 ft/s (137 m/s) | 328 ft/s (100 m/s) | 8.252 ft (2.515 m) | 49.41 ft (15.06 m) | 162.6 ft (49.6 m) | 426.0 ft (129.8 m) | 77 gr (5.0 g) | 370 gr (24 g) |

| .45 in (11.43 mm) | Martini–Henry | United Kingdom | 1,315 ft/s (401 m/s) | 869 ft/s (265 m/s) | 664 ft/s (202 m/s) | 508 ft/s (155 m/s) | 389 ft/s (119 m/s) | 9.594 ft (2.924 m) | 47.90 ft (14.60 m) | 147.1 ft (44.8 m) | 357.85 ft (109.07 m) | 85 gr (5.5 g) | 480 gr (31 g) |

| .433 in (11.0 mm) | Fusil Gras mle 1874 | France | 1,489 ft/s (454 m/s) | 878 ft/s (268 m/s) | 643 ft/s (196 m/s) | 471 ft/s (144 m/s) | 348 ft/s (106 m/s) | 7.769 ft (2.368 m) | 46.6 ft (14.2 m) | 151.8 ft (46.3 m) | 389.9 ft (118.8 m) | 80 gr (5.2 g) | 386 gr (25.0 g) |

| .433 in (11.0 mm) | Mauser Model 1871 | Germany | 1,430 ft/s (440 m/s) | 859 ft/s (262 m/s) | 629 ft/s (192 m/s) | 459 ft/s (140 m/s) | 388 ft/s (118 m/s) | 8.249 ft (2.514 m) | 48.68 ft (14.84 m) | 159.2 ft (48.5 m) | 411.1 ft (125.3 m) | 75 gr (4.9 g) | 380 gr (25 g) |

| .408 in (10.4 mm) | M1870 Italian Vetterli | Italy | 1,430 ft/s (440 m/s) | 835 ft/s (255 m/s) | 595 ft/s (181 m/s) | 422 ft/s (129 m/s) | 304 ft/s (93 m/s) | 8.527 ft (2.599 m) | 52.17 ft (15.90 m) | 176.3 ft (53.7 m) | 469.9 ft (143.2 m) | 62 gr (4.0 g) | 310 gr (20 g) |

| .397 in (10.08 mm) | Jarmann M1884 | Norway and Sweden | 1,536 ft/s (468 m/s) | 908 ft/s (277 m/s) | 675 ft/s (206 m/s) | 504 ft/s (154 m/s) | 377 ft/s (115 m/s) | 7.235 ft (2.205 m) | 42.97 ft (13.10 m) | 137.6 ft (41.9 m) | 348.5 ft (106.2 m) | 77 gr (5.0 g) | 337 gr (21.8 g) |

| .42 in (10.67 mm) | Berdan rifle | Russia | 1,444 ft/s (440 m/s) | 873 ft/s (266 m/s) | 645 ft/s (197 m/s) | 476 ft/s (145 m/s) | 353 ft/s (108 m/s) | 7.995 ft (2.437 m) | 47.01 ft (14.33 m) | 151.7 ft (46.2 m) | 388.7 ft (118.5 m) | 77 gr (5.0 g) | 370 gr (24 g) |

| .45 in (11.43 mm) | Springfield model 1884 | United States | 1,301 ft/s (397 m/s) | 875 ft/s (267 m/s) | 676 ft/s (206 m/s) | 523 ft/s (159 m/s) | 404 ft/s (123 m/s) | 8.574 ft (2.613 m) | 46.88 ft (14.29 m) | 142.3 ft (43.4 m) | 343.0 ft (104.5 m) | 70 gr (4.5 g) | 500 gr (32 g) |

| .40 in (10.16 mm) | Martini-Enfield | United Kingdom | 1,570 ft/s (480 m/s) | 947 ft/s (289 m/s) | 719 ft/s (219 m/s) | 553 ft/s (169 m/s) | 424 ft/s (129 m/s) | 6.704 ft (2.043 m) | 39.00 ft (11.89 m) | 122.0 ft (37.2 m) | 298.47 ft (90.97 m) | 85 gr (5.5 g) | 384 gr (24.9 g) |

References in culture[edit]

- In Rudyard Kipling‘s 1888 novella The Man Who Would Be King, two British adventurers use Martini–Henry rifles to establish their own kingdom in Kafiristan.[16]

- The Martini–Henry rifle was featured in the 1964 movie Zulu.[17]

- The Martini–Henry rifle is featured in the Battlefield 1 video game as the last unlockable weapon in the Scout class.

- The Martini–Henry rifle is mentioned in The Champawat Man-Eater by Jim Corbett in Man-Eaters of Kumaon(ISBN 978-81-291-4036-4).

Smith & Wesson Model 30

| Smith & Wesson Model 30 | |

|---|---|

| Type | Revolver |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Production history | |

| Manufacturer | Smith & Wesson |

| Produced | 1903-1976 |

| Specifications | |

| Length |

|

| Barrel length |

|

|

|

|

| Cartridge | |

| Action | Double-action |

| Feed system | Six round cylinder |

| Sights | fixed |

The Smith & Wesson Model 30 is a small-frame, six-shot, double-action revolver chambered for the .32 Long cartridge. It was based on the Smith & Wesson Hand Ejector Model of 1903, and could be had with either a blued or nickel finish. It was a “round butt” I-frame and was produced from 1948 to 1976.[1]

Contents

[hide]

History

From 1948 to 1957, this model was known as the “Model .32 Hand Ejector” and was built on the 5-screw I-Frame.

In 1958 the frame was redesigned to use four screws and a coiled mainspring as opposed to a flat or leaf spring and called the “Improved I-Frame”.

Three years later in 1961, the “I-Frame” was discontinued and the slightly longer 3-screw “J-Frame” replaced it.[1]

Variants

A square butt version first known as the “Model .32 Regulation Police” was made during the same time period as the “Model .32 Hand Ejector” and was eventually replaced by the Model 31 in 1958.

The Model 31 followed the same path as the Model 30 with regard to production dates.[1]

————————————–

.32 S&W Long

| .32 S&W Long | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.32 S&W Long (left) in comparison with .32 H&R Magnum and 7.62×38mmR Nagant

|

||||||||||||||||

| Type | Revolver | |||||||||||||||

| Place of origin | United States | |||||||||||||||

| Production history | ||||||||||||||||

| Designer | Smith & Wesson | |||||||||||||||

| Designed | 1896 | |||||||||||||||

| Produced | 1896–Present | |||||||||||||||

| Specifications | ||||||||||||||||

| Parent case | .32 S&W | |||||||||||||||

| Base diameter | .337 in (8.6 mm) | |||||||||||||||

| Rim diameter | .375 in (9.5 mm) | |||||||||||||||

| Rim thickness | .055 in (1.4 mm) | |||||||||||||||

| Case length | .920 in (23.4 mm) | |||||||||||||||

| Overall length | 1.280 in (32.5 mm) | |||||||||||||||

| Ballistic performance | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Source(s): Hodgdon [1] | ||||||||||||||||

The .32 S&W Long is a straight-walled, centerfire, rimmed handguncartridge, based on the earlier .32 S&W cartridge. It was introduced in 1896 for Smith & Wesson‘s first-model Hand Ejector revolver. Coltcalled it the .32 Colt New Police in revolvers it made chambered for the cartridge.[2]

Contents

[hide]

History[edit]

The .32 S&W Long was introduced in 1896 with the company’s first hand ejector revolver. The .32 Long is simply a lengthened version of the earlier .32 S&W. The hand ejector design has evolved some, but with its swing out cylinder on a crane, has been the basis for every S&W revolver designed since. In 1896, the cartridge was loaded with black powder. In 1903 the small hand ejector was updated with a new design. The cartridge stayed the same, but was now loaded with smokeless powder to roughly the same chamber pressure.[2]

When he was the New York City Police Commissioner, Theodore Roosevelt standardized the department’s use of the Colt New Policerevolver. The cartridge was then adopted by several other northeastern U.S. police departments.[3] The .32 Long is well known as an unusually accurate cartridge. This reputation led Police Commissioner Roosevelt to select it as an expedient way to increase officers’ accuracy with their revolvers in New York City. The Colt company referred to the .32 S&W Long cartridge as the .32 “Colt’s New Police” cartridge, concurrent with the conversion of the Colt New Police revolver from .32 Long Colt. The cartridges are functionally identical with the exception that the .32 NP cartridge has been historically loaded with a flat nosed bullet as opposed to the round nose of the .32 S&W Long.[2]

Current use[edit]

In the United States, it is usually older revolvers which are chambered in this caliber. The cartridge has mostly fallen out of use due to smaller revolvers chambered in .38 S&W Special being more effective for self-defense.[2]

The .32 S&W Long is popular among international competitors in ISSF 25m centerfire pistol, using high-end target pistols from makers such as Pardini,[4]Morini,[5] Hämmerli,[6] Benelli,[7] and Walther,[8] among others, but chambered for wadcutter bullet type.[9] The sporting variant of the Manurhin MR 73, also known as MR 32, is also chambered in .32 S&W Long.[10]

The IOF .32 Revolver manufactured by the Ordnance Factories Organization in India for civilian licence holders is chambered for this cartridge.[11]

Interchangeability[edit]

The .32 S&W Long headspaces on the rim and shares the rim dimensions and case and bullet diameters of the shorter .32 S&W cartridge and the longer .32 H&R Magnum and .327 Federal Magnum cartridges. The shorter .32 S&W may be fired in handguns chambered for the .32 S&W Long; and the .32 S&W Long may be fired in arms chambered for the longer H&R and Federal magnums; although the longer cartridges should not fit and must not be fired in arms designed for the shorter and less powerful cartridges.[12]

The .32 S&W Long and .32 Long Colt are not interchangeable.[2] At one time it was widely publicized that these rounds would interchange, but in truth it has never been deemed safe to do so.[2]

To Drop?

Then we hit the dark times of no .22 almost anywhere, at least around my neck of the woods, and from what I was seeing, we weren’t alone in that. Today, ammo is there, but it costs more than it used to, that’s for sure. However, those days just might be over with.

The Obama-caused bubble in ammunition prices seems ready to bust. Over the last few years gun owners have seen ammunition prices double or even triple. Handgun and rifleammunition has been hard to find at times and .22 long rifle ammunition tripled in price over the last 18 months. People would line up to buy ammunition at prices two and three times the level that they were just two years ago. But all of that is about to change . . .

Ammunition supply looks as though it is ready to catch up with demand. Centerfire pistoland rifle cartridges are available on most store shelves. When I walked into a local Wal-Mart this morning, their were over 30 signs on the ammunition case indicating a rollback of prices by 10-15%.

In classic economic fashion, the bubble was fueled by actions of the federal government. Many federal agencies bought enormous quantities of ammunition. The Obama administration’s actions fueled fear of coming shortages, gun bans, registration of ammunition sales, even potential low level warfare. All of this led to the current bubble of ammunition sales.

In response, the economy reacted the way free markets are supposed to work. Ammunition suppliers started running their manufacturing plants day and night, adding additional shifts. Importers scoured the world markets, trying to buy everything they could to satisfy the insatiable demand. Foreign manufacturers bumped up their production to try to fill the desire for more and more ammunition. Ammunition production was at the highest level ever for small arms, short of war.

However, as the post adds, this manufacturing won’t just stop. It’ll keep going until there’s a glut of ammo on the market. At that point, the Law of Supply and Demand kick in, and prices drop.

There are two ways to look at this. As a consumer, this is a good thing. Prices dropping means I can buy more ammo for the same money. That means more shooting. In other words, I’ll get more bang for my buck. Literally.

On the flip side, however, are the companies that make this ammo. Federal Premium is already having difficulties, after all, and I wouldn’t be surprised to see other companies having similar difficulties. After all, if their current budgets are based on selling ammo at X price, but they can only sell it at X-Y price, that’s going to play merry havoc with the revenue stream.

The question then becomes whether they can weather that storm.

Not that there’s much we can do except buy ammo and shoot a lot. Still, as a consumer, I’ll consider it my sacred duty to create as much spent brass as humanly possible.

You know, for the children.

Way too cool!

The Right Stuff!

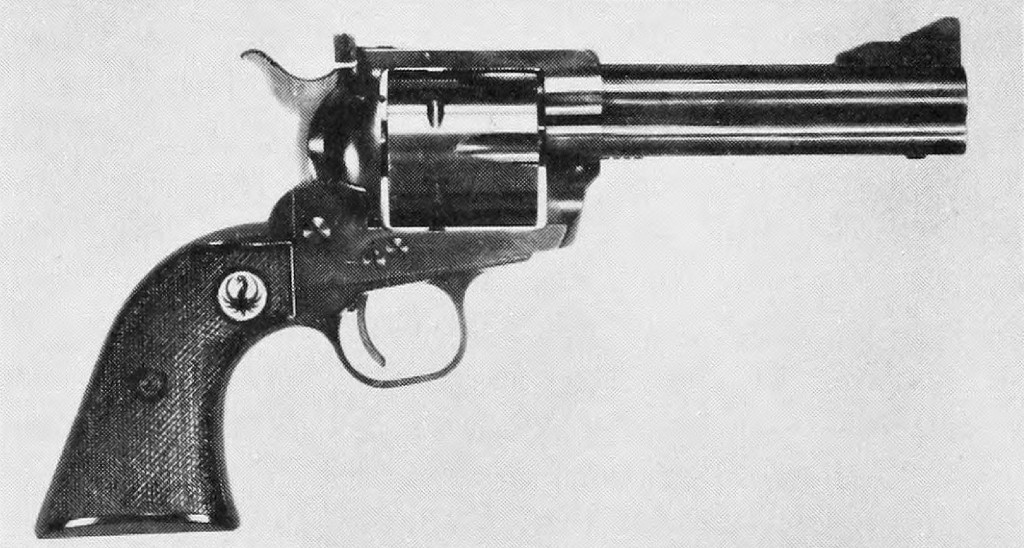

If you happen to stumble onto an online forum for Ruger firearms or single action revolvers you may find that the term “3-screw Blackhawk” appears quite frequently. You may also notice that some people have a certain esteem for the 3-screw Ruger Blackhawk over other Blackhawks and will go to great lengths to acquire one.

Many people new to revolvers probably have no idea what a 3-screw Ruger Blackhawk is, and even those who know what a 3-screw Blackhawk is probably don’t understand why revolver cranks covet these relics over all others. This post will explore a little of the Ruger Blackhawk history and tease out why the 3-screw Blackhawk is such a desirable gun and why collectors and non-collectors alike should seek one out for themselves.

A History of the Ruger Blackhawk

The history of the Ruger Blackhawk begins with the Ruger Single Six, a single action revolver based on the Colt Single Action Army Revolver of 1873 and chambered for the .22 Long Rifle cartridge. The Single Six was a popular seller for Ruger and indicated that there was a demand for single action revolvers in post WWII America.

In 1955 Ruger introduced the Blackhawk chambered for the .357 Magnum cartridge. The Blackhawk replicated the size of the old Colt Single Action in both frame size and grip size. The Blackhawk also had adjustable sights mounted on a flattop frame like many of the custom Colts and Colt Single Action target models.

Besides replacing the Colt flat springs with coil springs for better durability and using a frame mounted firing pin, the lock work of the Ruger Blackhawk was very similar to that of the Colt. The Blackhawk hammer had four distinct clicks that could be heard while it was brought back to full cock—which was characteristic of the Colts—and to freely spin the cylinder for loading the hammer had to be placed at half-cock, another characteristic of Colts and older single action revolvers. Because the lock work was so similar to that of the Colt, the Ruger Blackhawk had three screws on the side of the frame just as the Colts did. This model 3-screw Blackhawk is commonly referred to as the “flattop” due to its flat top strap.

The original .357 Magnum Ruger Blackhawk—The Flattop. Notice the flat top strap, adjustable sights, and the 3 screws in the side of the frame.

Around 1956 Ruger introduced a .44 Magnum version of the Blackhawk built on a larger frame to handle the increased pressures of the new cartridge. The .357 Magnum Blackhawk continued to be manufactured on the smaller Colt-sized frame, so Ruger was now producing Blackhawks in two frame sizes.

Starting in 1962 Ruger added “ears” to the top strap of the revolver around the rear sight. In Sixguns, Elmer Keith had recommended that Ruger add some protective “ears” to the rear sight to protect it from being knocked out of alignment when the rear sight was raised for long distance shooting. I am not sure whether Keith actually influenced the decision by Ruger to add the “ears”, but Sixguns was released in 1955 and a revised edition was released in 1961—both predating the “ears” on the Blackhawk—so the ears may be his handiwork.

In 1973 wholesale changes were made to the Ruger Blackhawk. The lock work was changed from that of a Colt to something completely new. Instead of setting the hammer to half-cock for loading, the loading gate now regulated the cylinder for loading and the hammer no longer had the four clicks found on previous Blackhawks and Colts. A transfer bar safety was also added which made the gun safe to carry with six rounds in the cylinder. As a result of the changes to the inner workings of the Blackhawk, there were now only two screws on the side of the frame.

In addition to the inner changes to Blackhawk, there was one notable outward change. Probably to simplify manufacturing, all Ruger Blackhawks from 1973 onward, regardless of caliber, would be built on the larger .44 Magnum sized frame. This revised revolver was renamed and released as the New Model Blackhawk, thus ending the life of the 3-screw Blackhawk.

What’s the big deal?

“So,” you may be asking, “what’s so special about the 3-screw Blackhawk? Isn’t it just an older Blackhawk? Why would a non-collector care about it?”

It’s true that the 3-screw Blackhawks are coveted by collectors for their age and status as the inaugural model the popular Ruger Blackhawk series (particularly the flattop 3-screws). But what many people overlook is that the most important change that came with the New Model Blackhawk wasn’t the new innards, it was the new body the innards were put in.

Over the course of the Blackhawk’s life it had increased in size with each revamping. In 1955 the Blackhawk was released with a grip and frame the size of the Colt Single Action Army—the gun by which all other single action revolvers are judged; a gun which had the perfect combination of size and strength for someone wanting an all-around revolver for packing into the woods or wherever he may wander; a gun which pointed so gracefully that the sights were almost unnecessary at close range.

In 1962 the “ears” were added to the Blackhawk but so was a new grip frame. The new grip was slightly larger than the previous Blackhawk grip, and consequently, larger than the Colt’s.

Some people liked the new grip while others preferred the smaller grip found on the flattop, but the change was minor and the 1962-1972 Blackhawks still handle and point well. Besides, replacing the larger grip frame on a Blackhawk with a smaller one is a relatively minor modification.

The blow came in 1973 when all Blackhawks were moved to the large frame originally built to contain the pressures of the .44 Magnum. Now all Blackhawks—whether .44 Magnum, .45 Colt, or .357 Magnum—would be built on this hulking frame.

The larger frame was obviously needed to safely chamber the .44 Magnum, and the .45 Colt certainly benefited from the larger frame size as it essentially became a .45 Colt Magnum. But the poor .357, one of the most ideal rounds for packing into the woods, receives no benefit from the larger frame at all.

The medium sized frame of the Colt Single Action Army and 3-screw Blackhawks was more than enough beef to contain .357 Magnum pressures. Heck, the .357 Magnum is safely fired in J-Frame Smith & Wesson revolvers without fear of blowing up. The .357 Magnum deserves better than being shoved into a bulky and heavy frame; it deserves a frame which matches the versatility of the cartridge itself; a frame which can be comfortably carried all day in the woods whether you are on the prowl for small game, large game, or even nothing at all.

Even the .45 Colt, a cartridge which had always been housed in the larger frame Blackhawks, is perfectly fine in the medium framed guns. Sure, the .45 Colt in the large frame Blackhawks is capable of extreme power that matches or exceeds .44 Magnum, but is it really necessary?

The .45 Colt’s legacy was built on the medium framed Colt Single Action Army, where it developed a reputation for throwing heavy pieces of lead at moderate velocities. Who could realistically need more power than a 255 grain lead bullet traveling at 900 feet per second? Perhaps more importantly, who would want to endure the recoil associated with the increased power?

Because of the size of the 3-screw Blackhawks, they became popular platforms for people to build custom revolvers on. The most popular customization was to rechamber the .357 3-screw Blackhawks to .44 Special—a cartridge which needs only the medium sized frame to reach its full potential and which Elmer Keith pushed to near .44 Magnum velocities in his custom Colt Single Actions. Skeeter Skelton had at least a couple of these conversions done and it remains a popular conversion today. If a single action aficionado is looking for a good packing or working gun, the 3-screw Blackhawk is often the revolver they turn to.

A happy ending?

Once thought to be lost forever, the medium framed Ruger revolver has made a comeback in a big way. Starting with the introduction of the New Vaquero in 2005, Ruger put the medium sized single action frame with Colt sized grips in production. These new guns still use a transfer bar safety and New Model Blackhawk lock work for the most part, but the important thing is that they returned to the svelte sized frame and grips of the old 3-screw Blackhawks and Colt Single Actions. The New Vaqueros had fixed sights, so they were no replacement for the 3-screw Blackhawks, but it was an important first step.

Shortly thereafter, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the first Blackhawks, Ruger released a limited run of .357 Magnum New Model Blackhawks built on the medium sized New Vaquero frame with adjustable sights and a flat top strap, finally coming full circle. Unfortunately, this medium framed .357 Magnum New Model Blackhawk was only a limited run and today the .357 Magnum New Model Blackhawk has returned to being produced only in a large frame.

For a comparison of the sizes between the original Colt Single Action, the 3-screw Ruger Blackhawk, the New Model Ruger Blackhawk, and the newest medium frame Blackhawk, check out this article over at Gunblast.com. They have a table with various measurements from these guns for comparison purposes. When looking at the table, keep in mind the dimensions for the “Old Vaquero” are the same as the large frame New Model Blackhawks and the “New Vaquero” is the same size as the medium frame New Model Blackhawks.

Happily, with the help of Lipsey’s, Ruger was persuaded to introduce a .44 Special New Model Blackhawk built on the medium sized flattop frame previously used for the 50th Anniversary Blackhawk. Lipsey’s special order of these revolvers was so successful that Ruger added the revolver to their regular product line and now they can be ordered from almost any firearms retailer.

Lipsey’s also did a special run of .45 Colt New Model Blackhawks on the medium sized flattop frame, and these can be ordered from a Lipsey’s dealer. However, due to the success of the large frame .45 Colt Blackhawk, I don’t believe we will ever see this item as a regularly cataloged product from Ruger itself.

So, on the bright side, we now have the .44 Special New Model Blackhawk; a revolver which fires a spectacularly versatile cartridge in the handy medium sized frame. Elmer Keith had written about his hopes for such a gun in Sixguns in 1955 and Skeeter Skelton had dreamed of such a gun as well. Finally, fifty years after the Blackhawk was introduced, the wishes of these two men—and many other sixgun enthusiasts—came to fruition.

On the other hand, if someone wants a .357 Magnum Ruger single action revolver on the medium frame they have no viable options currently being produced. The New Vaquero is offered in .357 Magnum and is built on the medium frame, but it lacks adjustable sights. One is forced to look on the used market for a 3-screw Blackhawk or the 50th Anniversary New Model Blackhawk. The Anniversary models regularly sell for more than the 3-screw Blackhawks, plus the Anniversary models only came with the 4.625 inch barrel, so the 3-screws are still the best option.

I have hopes that someday Ruger will produce the .357 Magnum New Model Blackhawk on the medium flattop frame as a regular catalog item. After all, the medium flattop frame is already in production for the .44 Special New Model Blackhawk, the medium .357 Magnum cylinders and barrels are already in production for the New Vaquero, and the .357 Magnum has no need to be housed in a large frame revolver. To me, it looks like all the pieces are in place and I sincerely hope that this ideal .357 Magnum revolver can somehow be produced and reclaim the romance and tradition of the 3-screw Blackhawks of old.