Muskets

This feature article, “Ruger: Hencho en Mexico,” appeared originally in the July 2005 issue of American Rifleman. To subscribe to the magazine, visit the NRA membership page and select American Rifleman as your member magazine.

Colonel Rex Applegate was born in Yoncalla, Oregon, in 1914. He graduated from the University of Oregon in 1939 with a degree in business administration. That same year he joined the U.S. Army as a second lieutenant in the Military Police Corps and eventually rose to the rank of colonel. Applegate had an interesting and colorful career in the service. He was the head close-combat trainer for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) during World War II and became the acknowledged expert in close combat, working on the design of combat knives with British Commandos. After returning to the States, Applegate was assigned to special duty at “Shangri La,” now known as Camp David, Md., to guard President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

After a distinguished military career, Col. Applegate retired from the regular Army with a combat disability in 1946. A residence with a dry, warm climate was recommended. While in the military Applegate became acquainted with an officer who had retired to Mexico. On his recommendation Applegate visited Mexico and decided the climate was right and commercial opportunities there looked promising. During this time the officer who recommended Mexico to Applegate had obtained a distributorship and opened an assembly plant for Nash Motors, in Mexico City, called “Nash Motors of Mexico.” Applegate was employed in 1947 as service manager.

The colonel’s interests did not lie in automobile production but in what he knew best: firearms, or at least a firearm-related business. During the war, Applegate became very well acquainted with the management at Smith & Wesson. It was through that acquaintance that he was able to break into the firearm business. Dave Murray, S&W sales manager, contacted Applegate in Mexico. The timing was perfect. Applegate was able to obtain 1,000 .22 S& W K22 revolvers. The new K22 Masterpiece, a replacement for that model, had been introduced in the States and Smith did not want these 1,000 revolvers on the U.S. market. Applegate marketed the guns in Mexico. The venture was highly profitable as the Mexican population was eager for any type of firearm.

Applegate resigned his position at Nash Motors to form his own company, Cia Compania Importada Mexicana (The Mexican Importing Company). Financing was furnished by Frank Sanborn, owner of the famous Sanborn Drug and Restaurant of Mexico City. Applegate operated in Mexico from 1948 to 1955 as factory representative for S&W, Remington, and Peters Ammunition, as well as a U.S. chemical company that produced a line of tear gas. He also served as representative for a number of U.S. fishing tackle firms, as well as other allied firms in the sporting goods industry.

Laws governing import duties in Mexico were changed in 1955. Prior to that time import duties were quite low. Afterward, not only were import duties raised, but products sold in Mexico were required to be 40 percent manufactured in Mexico. A manufacturing and assembly facility was needed, and Applegate established Armamex, S.A. The Armamex manufacturing and assembly plant was located in the city of Pachua, State of Hidalgo, approximately 90 miles north of Mexico City. He was president and in charge of sales and retained all U. S. contracts. Financing was furnished by W.O. Jenkins, a wealthy American residing in Puebla, Mexico. Eugene Everhert, an American gunsmith and long-time Pachua resident, was hired as plant manager.

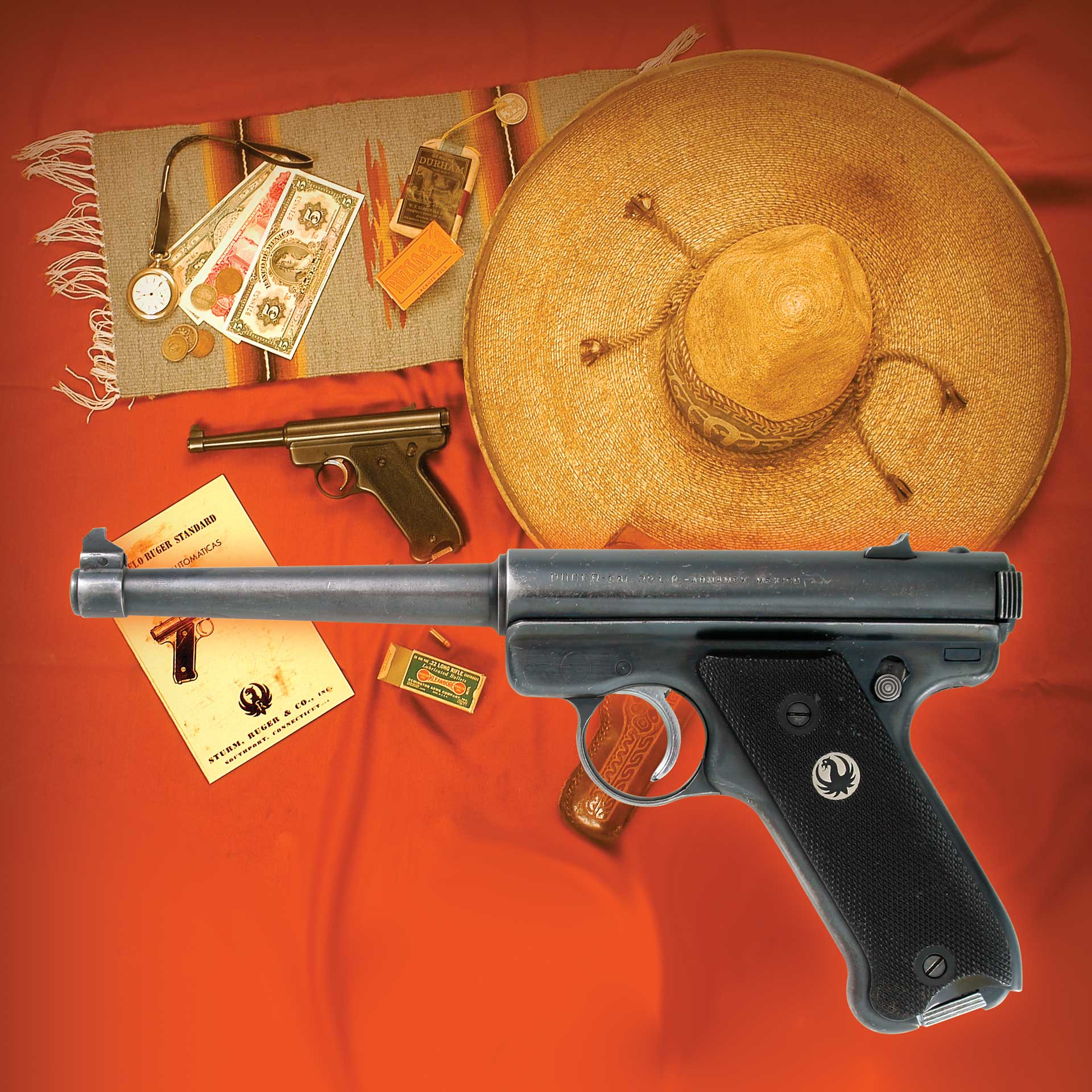

Everhert was an engineer at a local silver mine until that time. P.O. Ackley was brought in for assistance in setting up the new plant and to perfect Armamex’s barrel making operation, and Ackley’s employment was on a temporary basis. Another American gunsmith, who also lived in Mexico, was in charge of assembly and quality control. Management was basically American, while the labor force was Mexican. Firearms assembled in the plant were stamped “armamex, mexico” and/or “hecho en mexico” (made in Mexico).

Sales were through Cia Compania Mexicana. Applegate’s companies served a network of approximately 200 Mexican arms dealers. Firearms consisted of a single-shot .22 rifle manufactured entirely in the Armamex factory and a single-barrel, Iver-Johnson shotgun. Stocks and barrels for the shotguns were produced by Armamex to comply with the local 40 percent manufacturing law. These economical hunting arms seemed to fill the needs of the local population, and shotguns and .22 rifles were not considered a security threat by Mexican military officials. The Mexican military was the source for licenses and permits, and revolutions aren’t usually fought with either type of arm.

With the successful marketing of these economical long guns Applegate decided to offer a line of better-quality sporting arms. He made a trip north to the United States to meet with manufacturers in order to fill this new firearm line. This was either late 1955 or early in 1956. He struck a deal with Bill Donavan of High Standard for several hundred .22 Sport King pistols. In a meeting with Robert L. Hillberg, owner of Whitney Firearms, Inc., of New Haven, Conn.,

Applegate made a deal for 200 .22 Whitney Wolverine pistols. In a letter from Mr. Hillberg, he (Hillberg) recalled how the transaction was accomplished, “Bob Dearden was our key man and the entire transaction was with him. Bob devised a method of identifying the individual component parts and packaged them in a manner Applegate could receive and assemble the original guns without mixing any of the parts. Rex shipped the parts to a company in Texas. How he got them into Mexico, I have no idea.”

Applegate’s close friend W.H.B. Smith, firearm expert and author, arranged for a meeting with William B. Ruger, Sr., of Sturm, Ruger & Co. Ruger and the colonel struck up an instant friendship. The two men shook hands and made an informal agreement. Applegate purchased 200 Standard Model Ruger .22 pistols, and they were shipped to the American Firearms Company at Brownsville, Texas, (a company Applegate had organized with U. S. licenses for purchasing and exporting firearms). A representative of Armamex was sent to Texas to receive the shipment and they were disassembled there. Parts were marked and bagged with caution not to mix the parts from one gun with another. The parts were imported to Mexico, but Applegate’s Mexican import permits covered parts only, not complete firearms. The High Standard and Whitney pistols were shipped in a similar manner. These transactions were an experiment and not repeated.

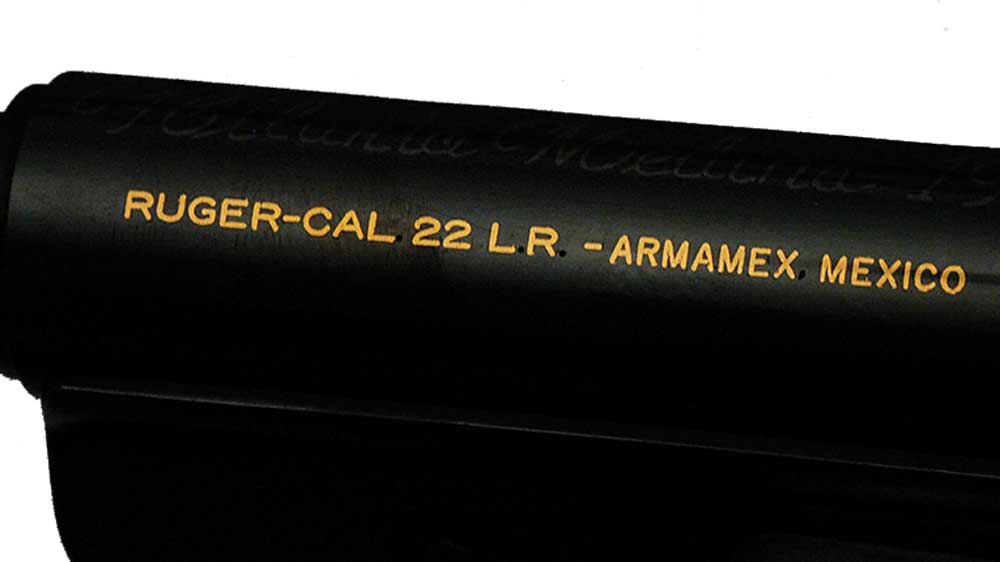

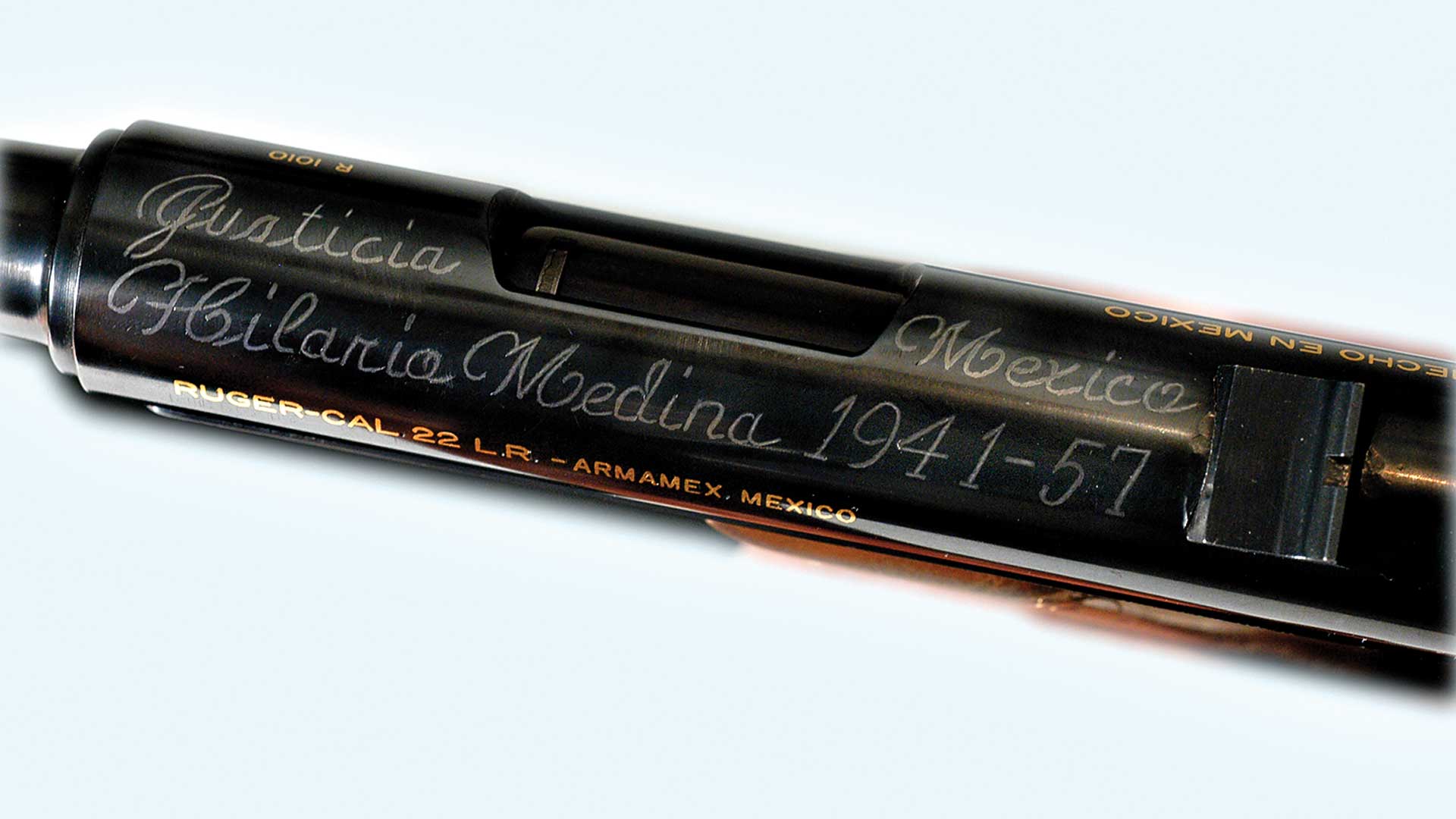

On arrival at Armamex the pistol parts were roll-marked, blued, and assembled. The Ruger pistols were serially numbered with the letter prefix “r.” Rolled on receiver’s right was “hecho en mexico,” and the left side was marked “ruger cal. 22 l.r. armamex mexico.” The Whitney and High Standard pistols were marked “armamex mexico.”

The finished pistols were then shipped from Armamex to Cia Compania Mexicana and on through the Mexican network. All the Ruger pistols were shipped except one that Applegate put back and later gave to Bill Ruger for his personal collection. Although successful, Applegate—realizing the position he and his companies could be placed in with the Mexican authorities—elected to discontinue the importing of either complete U.S. handguns or parts. His Mexican firearm operation was built around rimfire single-shot rifles and shotguns, and Applegate decided to return to that. His degree in business administration had served him well.

Armamex operations continued until 1962 when Applegate was recalled by the military for special duties in relation to riots in the United States, and he left Mexico in 1963.

Armamex continued to operate for several more years, but it eventually folded due to poor management—along with increasing government interference. The Mexican government ordered seizure of all firearms in the early 1970s. Sporting goods stores were forcibly closed, and inventories were confiscated.

Rules can be bent in Mexico if the right generals are approached, and money put in the proper pockets. Some of the Armamex pistols have found their way out of Mexico, but fewer than a dozen Armamex Ruger pistols are known in private collections—and even fewer High Standard and Whitneys have been located. All of Applegate’s records and photographs on the Armamex operation along with guns from his personal collection were confiscated.

Sadly, Rex Applegate died on July 14,1998, at the age of 84. One of this great man’s many legacies remains a handful of Ruger pistols that were “hecho en mexico.”

A couple years ago I was working security at a bar in northern Virginia. I overheard a table of college kids arguing about gun rights and gun control and it was getting far too emotional so I did what any sane combat veteran would do and attempted to exfiltrate. I must not have withdrawn as surreptitiously as I intended, because I was stopped in my tracks when a 5-foot-nothing brunette seemingly leapt in front of me and blurted out “excuse me, can you help us?”

I’m sure I must have looked irritated as I cycled through the possible quips and excuses I considered available to me but being uncertain that she wasn’t some Senator’s daughter, I caved: “What’s up?”

She basically leads me to this table of 2 other females (probably both named Karen) and a very soft looking male.

Becky: “So, we were just talking about current events and, you know. So, you look like you’re probably in the military, right? Like the Army?”

(When you accuse someone of being in the military you probably don’t need to give an example.)

Me: “Similar.. yea”

Becky: “Right. Okay. So, do you think civilians should be allowed to own guns?”

Me: “Most of us. Yes.”

Becky: (clearly not happy with my answer) “Okay, so, why do you think you need a gun?”

(At this point it’s almost 2am and I’ve just given up on patience. Hold my beer.)

(With intentionally overt condescension): “Oh, honey, I don’t. I don’t need a gun.”

Becky stares at me blankly, so I continue, but with a more serious tone:

“I could follow you home, walk up your driveway, and beat you to death with the daily newspaper.

I could choke you to death with that purse.

I could take a credit card, break it in half, and cut your throat open with it.

With enough time and effort I could beat your boyfriend here with a rolled up pair of socks.

I could probably dream up six dozen other ways I could easily end your life if you gave me an hour or so.

If I wanted to, I could wrap my hand around that beer mug and kill all four of you before you could make it to the exit. The worst part is, in your utopian little fantasyland, there ain’t a thing any of you could do about it.

I don’t need a gun.

You need a gun.

You need a gun because of men like me.”

Russians

Russian gangster : “you’ll never take me alive !!”

Russian police: “who said we wanted you alive?”

Tankers really hate to go into built up areas for just this reason. Especially when they don’t have proper Air Support & Dismounted infantry around. Time to call in the Arty and blow the place apart! Oh Well! Grumpy