Regardless if you procured an outdated rifle from an older family member, via a gun-show purchase or through some other method, you hope the vintage shooting iron still hurtles projectiles downrange accurately. You may get lucky with that classic gun, but you also may struggle with it spitting bullets irregularly like a malfunctioning baseball pitching machine. You might address the issue via a gun shop visit or DIY gunsmithing. Additionally, consider these five upgrades as possible remedies for errant rounds.

Before you give your old friend a major makeover, do some research. Use the serial number, model number and other details of the rifle to determine its age. First, the firearm may be an actual antique, and if you have ever watched the PBS program “Antiques Roadshow,” you understand that modifying the character of an item typically decreases its value.

Second, older firearms were not manufactured with the same specifications as their counterparts today. Those older designs may not be up to the task when launching the higher pressures of modern ammunition. Risk of injury or even death could result in a mismatch. Seek out advice from the manufacturer and trusted firearm experts to determine whether your old rifle should return to the field or rest comfortably above the fireplace mantle.

Spring Cleaning

If given the green light to transform an elderly rifle, you can start easily with spring cleaning. Give that old firearm a good scrubdown from end to end. Whether the past owner neglected regular cleanings or simply put the rifle away after the last deer season without cleaning it, a good cleaning could remove performance-affecting gunk throughout.

Make sure the firearm is unloaded and then disassemble, with the help of manufacturer guidelines. This gives you access to all nooks and crannies containing crud. Clean from the breech end with the help of a bore guide as you push your cleaning rod toward the bore. Your goal is to remove all deep-seated copper fouling in the barrel. Repeat until your patches come out clean.

Using gunsmithing tools and solvents, clean the bolt, action, trigger assembly and any mechanisms that hold cartridges, including springs. Afterwards, lubricate lightly with rust prevention products and foul the barrel with one or two shots before assessing accuracy. Fouling removes traces of oil and cleaning solvents, plus it pads the rifling with copper and powder residue. If your rifle shoots accurately and you are happy, your improvements may be complete.

New Fuel

After your lawn mower sits all winter, a dose of new fuel helps spark it back to life. New ammunition could do the same for that older rifle, especially after a deep cleaning. Set aside any stockpiles of nostalgic ammunition that may have come with the rifle and explore the latest options. After establishing that your rifle can handle newer advancements in ammunition, research selections that are receiving kudos in articles, forums and blogs. A lot has changed since the original Peters deer hunting cartridges were last available. Technological boosts, such as Hornady’s revolutionary use of Doppler radar to aid bullet design, have led to projectiles that fly more accurately and expand with consistent results.

Handloading may be your thing, and it provides an environment where you can safely create your own recipe for accuracy success. Not only can you tailor loads to match the era of your rifle’s specifications, but you can also tweak them until a bullet flies to your objective.

Whether you test with factory updates or handloaded perfection, new ammunition can make an older rifle shine in performance.

Stock It

Rifles of yesteryear traditionally featured stocks crafted from wood. Some of these were elegant examples of artistic craftsmanship. Others might be held together with a firm wrapping of electrical tape. Unfortunately, the wood stock could be a major culprit in marginalizing your rifle’s precision usefulness.

With weather variables (humidity being the worst), wood could swell and apply pressure to the barrel or receiver, affecting accuracy. Fortunately, you have several easy fixes to the issue. The first fix is to glass- or pillar-bed the action along with free-floating the barrel. Order either kit from Brownells and do it yourself or find a gunsmith for the job. Before you chart this course, consider again the antiquity value of the rifle. This alteration could reduce its value with the “Pawn Stars” employees.

To protect vintage value, ditch this option and shop for a replacement stock. Technically advanced stock systems, crafted of a single component or layers of polymer, graphite and even Kevlar, provide a quality replacement for pressure issues. You can even peruse laminated wood options if you favor that feel. Plus, if you ever wish to sell your heirloom, simply swap back the stock and advertise it as original. Magpul, Hogue, Boyds and others manufacture stocks that are bedded and easy to install.

I See Clearly Now

Despite a reemerging spotlight on open-sight rifles, most of us rely on a riflescope to perfect our aim. Your rifle may have arrived with a scope on it, but evaluate the optic to see if it is better gifted or tossed. Improved glass and multilayer coatings, trajectory reticles, focusing abilities and first- and second-focal plane reticle choices can improve your aim.

Technologically advanced optics systems, like SIG Sauer’s Sierra3BDX system, Bluetooth communicate between the riflescope and the rangefinder to automatically adjust the reticle. The 1970s Weaver riflescope that tops your grandfather’s rifle cannot do that trick. While swapping scopes, consider upgrading hardware, including new rings and bases. If yesteryear tugs at your heart, save the old hardware and scope to restore that rifle to a past era when it completes your tour of duty.

Crisp and Clean

Lastly, like NASA, a clean launch ensures a good start to your mission. A new trigger can guarantee a good bullet launch. It is possible your earlier cleaning returned the trigger to a quality state or a gunsmith could tune the old trigger into a functioning mechanism with a sweet spot. Companies such as Timney and Geissele manufacture replacement trigger systems for a variety of firearms. Study up on an upgrade for your project rifle and consider having work completed by a competent gunsmith. A trigger needs to be adjusted according to manufacturer recommendations or you need to be responsible if you decide to set your trigger for a more sensitive release.

Many precision rifles have adjustable triggers from 1.5 to 4.5 pounds. A setting between 2.5 and 3.5 allows you to depress without jerking and keeps your rifle safe. This is critical, as a trigger adjusted too light could accidentally go off simply by slamming the bolt closed.

A rifle with senior-citizen status does not have to be sent to the display case. With some creative ingenuity, it can still play a major part in your future hunts.

By Larry Keane

Connecticut’s Democratic Gov. Ned Lamont doesn’t have the celebrity status of some of his gun control colleagues like New York’s Democratic Gov. Kathy Hochul, New Jersey’s Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy or California’s Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom. His recent gun control proposal arguably outdoes them all, though.

Connecticut’s governor ripped a page from the Biden administration playbook and attempted to divert attention from failures to address rising crime by calling for increased gun control. Gov. Lamont said in a press conference announcement, “You’re not tough on crime if you’re weak on guns. We’re going to continue to stay tough on guns.”

That’s obfuscation. Gov. Lamont is miring two unrelated issues to confuse voters in a re-election year. He’s running again to keep his job and instead of admitting he’s done nothing to address criminal activity in the state, he’s proposing policy changes that would crush firearm retailers and individual gun rights of law-abiding citizens.

Read that again. Gov. Lamont isn’t proposing to target criminals, but those who abide by the law.

Layered Bureaucracy

Gov. Lamont explained he was proud that Connecticut already had among the nation’s strictest gun laws. “But that’s not good enough. I’ve just been shocked by what I’ve seen over the past couple of years,” he added.

What he saw in his state are sky high legal firearm sales, the most in five years. That’s occurring in the middle of “defund the police” schemes embraced by Hartford, New Haven and Bridgeport, and rising crime in those cities. Gov. Lamont’s proposals would do little to hold criminals to account.

Chief among Gov. Lamont’s gun control wish list is the creation of a state-level firearm licensing agency to track and enforce Connecticut’s strict laws.

“The lack of state licensing for gun dealers makes it difficult for the Connecticut Department of Emergency Services and Public Protection to enforce the laws,” the governor said.

The governor is ignoring, of course, that every firearm retailer in Connecticut is already required to be licensed and regulated by the federal government through the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF).

Another state-level licensing agency is more than just layered bureaucracy. It’s a tool to grind local gun shops into oblivion.

Gov. Lamont’s administration has a track record of dismissing and outright ignoring gun owner and firearm retailer rights and concerns. Just last year officials from the Lamont administration ignored retailer requests for robust guidance and assistance during his poorly-managed transition of the state’s background check system. Now, Gov. Lamont’s office wants to expand their grip on power and licensing authority with little to no desire to dedicate resources to support the proposals.

That won’t stop criminals from illegally-selling guns on the black market or stealing them. The only people impacted by this legislation will be those trying to follow the laws in the first place. Gov. Lamont’s goal is to use the new laws as a bludgeon against the lawful industry ensuring law-abiding Connecticut residents can exercise their Second Amendment rights.

Blue State Red Tape

Gov. Lamont’s proposals include mandatory registration of so-called “ghost guns” manufactured prior to the state’s already existing 2019 ban, expanding a ban on so-called “assault weapons” purchased prior to a 1993 state law requiring registration, expanding firearm storage laws even though Connecticut already has mandatory storage laws and enactment of a “stop and frisk” policy for police to check carry permits for those who are openly carrying firearms.

Second Amendment supporters are howling. Connecticut’s highest-ranking Republicans on the state’s House Judiciary and Public Safety Committee criticized the governor.

“While lawful Connecticut citizens are, on an almost daily basis, being victimized by brazen criminals with little fear of punishment, the governor has chosen an aged election-year tactic of attacking law-abiding gun owners in an effort to distract from his administration’s utter failure to address criminal justice policies,” Reps. Craig Fishbein and Greg Howard said.

Other Second Amendment and Constitutional rights groups, including the non-partisan Connecticut Citizens Defense League, (CCDL) denounced the proposals. CCDL stated parts of Gov. Lamont’s gun control package, “is out of touch with the people of Connecticut as thousands of residents have become new permit holders within the last year.”

Connecticut is witnessing the same bait-and-switch that President Joe Biden attempted in New York City. He traveled there to address crime, only to pitch a series of gun control proposals. The president didn’t offer any plan to get serious about tackling crime. The same thing is coming out of Hartford. Unfortunately for Connecticut, the governor is just as unserious about locking up criminals as he is serious about locking down gun stores.

Larry Keane is Senior Vice President of Government and Public Affairs and General Counsel for the National Shooting Sports Foundation, the firearms industry trade association.

The Lewis Machine Gun, with its large cylindrical jacket surrounding the barrel and distinctive top-mounted pan magazine, is one of the most recognizable military arms of all time. While many are aware of the Lewis gun, the story of its tenure in U.S. service is not as well known. It may be surprising to some that, although developed by a U.S. Army officer, the Lewis gained the majority of its fame in the service of other nations. Despite its proven effectiveness, the story of the American Lewis is a mixture of intra-service rivalry, petty professional jealousy and incompetence at the highest level of the U.S. Army Ordnance Department.

The genesis of the Lewis machine gun dates to 1910 when Isaac Newton Lewis, a colonel in the U.S. Army Coast Artillery, became affiliated with the Automatic Arms Company of Buffalo, N.Y. The fledgling arms firm hired Col. Lewis to develop and refine a light machine gun based on a design originally patented by an American inventor, Samuel N. McClean. Although McClean’s design had some interesting features, it was rejected by the American military after little more than a cursory glance. The Automatic Arms Company’s financial backers felt McClean’s basic design could be substantially improved and Col. Lewis was the man to tackle the job. By 1911, Lewis had developed an improved prototype, and the U.S. Army Ordnance Department agreed to test it.

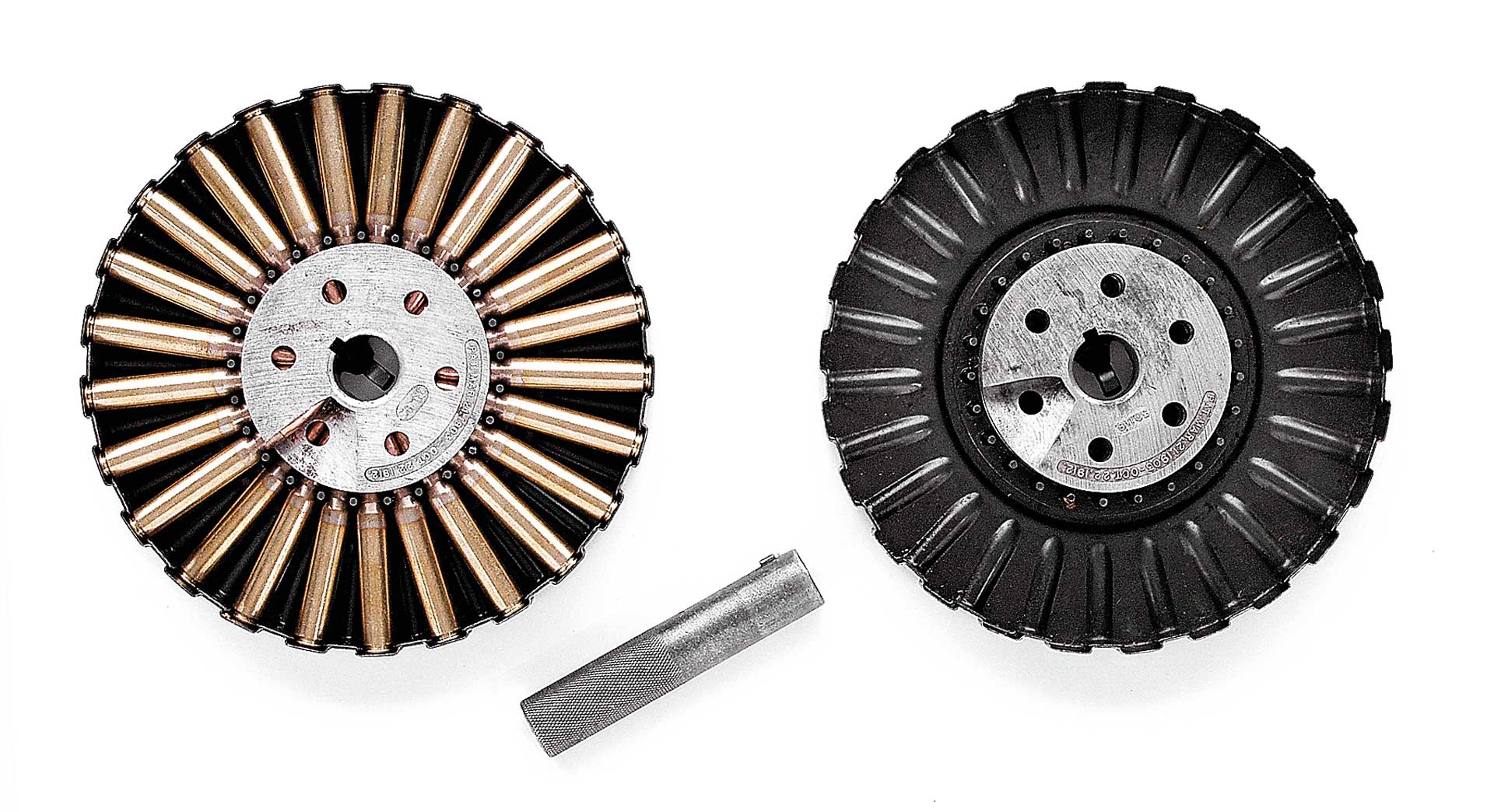

The Lewis had several novel features, including a top-mounted pan magazine and a unique cooling system that utilized a radiator jacket which encased, and was slightly longer than, the barrel. When the gun was fired, the muzzle blast forced air inside the radiator and over the barrel to aid in cooling. The prototype weighed about 25 lbs., was chambered for the standard U.S. .30-cal. M1906 cartridge (.30-’06 Sprg.) and fired fully automatically at the rate of approximately 750 rounds per minute. In addition to the prototype, Lewis and his backers had four other examples fabricated for the upcoming Ordnance Department tests.

In one of the early tests, Col. Lewis arranged a demonstration to have his machine gun fired from an airplane in order to demonstrate its flexibility. On June 7, 1912, a prototype Lewis machine gun was fired by Captain Charles Chandler from a Wright Type B biplane piloted by Lt. T.D. Milling. According to contemporary reports, there were multiple hits made on the ground target. This demonstration was intended to impress the assembled Ordnance Department brass with the potential capabilities of the new arm. Unfortunately for Col. Lewis, the demonstration did not have the intended effect. Many of the senior officers present felt that firing a machine gun from an aircraft was a foolish stunt that would never be of any practical value.

The remaining demonstrations and trials fared little better, and the gun came in for a lot of criticism. Some of the complaints were valid while others fell firmly in the nit-picking category. After the tests were completed, Col. Lewis was informed that his gun would not be recommended for adoption or further development. Even though it performed relatively well in the various tests, there were several reasons, if not excuses, proffered for rejection of the design, including budgetary concerns and the fact that the machine gun served essentially the same purpose as the standardized U.S. M1909 Benet-Mercie Machine Rifle.

Reading between the lines, one cannot help but assume that at least part of the reason for the conclusions of the evaluation board was that some officers senior to Col. Lewis, especially Chief of Ordnance Gen. William Crozier, were jealous that a fellow officer might gain a measure of fame and fortune by developing such an arm.

Col. Lewis was upset enough by the turn of events to call the members of the test board “ignorant hacks.” Obviously, this was not conducive to furthering his career in the U.S. Army and, shortly afterward, Lewis submitted his retirement papers and left the service.

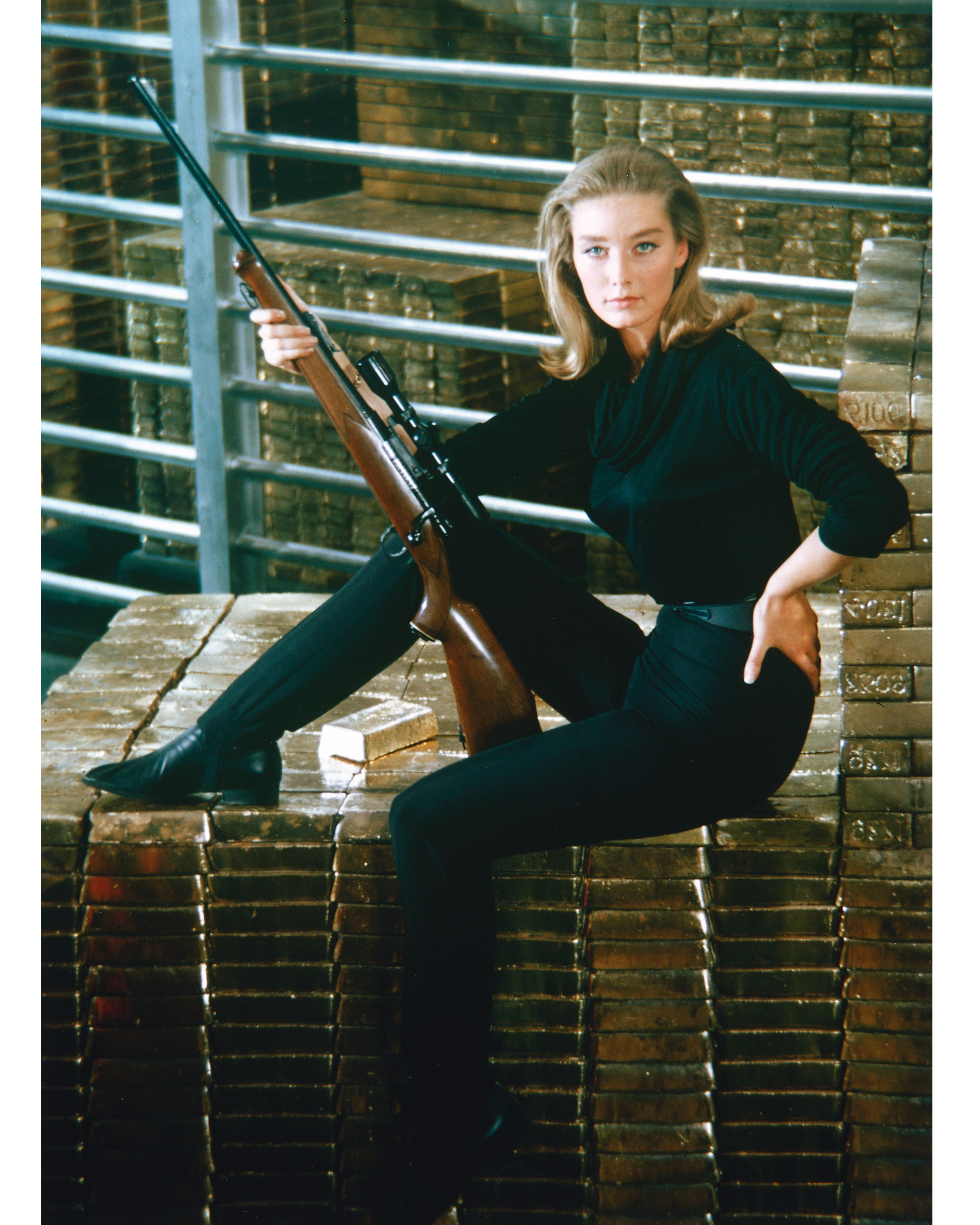

In early 1913 Lewis took the four prototypes to Europe, and the gun was tested by a number of foreign governments. The reception that the Lewis machine gun received overseas was in marked contrast to that encountered in the United States just a few months before. With the threat of war on the horizon, unlike the hide-bound U.S. Army, several European nations were interested in acquiring modern arms. Great Britain and Belgium were quite impressed with the Lewis, and both nations soon adopted it. Great Britain made arrangements with the Birmingham Small Arms Company (BSA) for manufacture of a .303 British version, and Belgium put the gun into production at the small arms factory in Liege. The British standardized the Lewis as the “Gun, Machine, Lewis, .303 in., Mark I.” It weighed just over 28 lbs. and employed a 47-round, top-mounted pan magazine. BSA eventually manufactured 145,397 Lewis guns during World War I. In 1915, in order to augment production, the British contracted with the Savage Arms Corporation of Utica, N.Y., for manufacture of .303 Mark I Lewis guns.

World War I broke out in Europe shortly after the Lewis production began. There were no other arms in the Allied arsenal comparable to the Lewis, and it immediately gained an enviable reputation as an effective and reliable light machine gun. To take advantage of the Lewis’ portability and firepower, the British formed infantry machine gun killer teams to eliminate German machine gun emplacements. These teams were used with notable effectiveness, due in no small measure to the lethality of the Lewis. The Germans reportedly attempted to capture, and use, as many Lewis guns as possible and gave the gun the nickname “Belgian Rattlesnake.”

The Lewis’ sterling performance was not lost on its American proponents. Some insightful individuals recognized it would only be a matter of time until America was drawn into the conflagration raging in Europe and pressed for adoption of the Lewis by the United States. Likely due in large measure to the lingering bitterness on the part of some officers, the U.S. Army Ordnance Department still considered the Lewis to be unsatisfactory. However, in 1916, the U.S. Army did agree to purchase 350 Lewis guns from Savage for use in the Mexican Punitive Expedition. Despite the non-standard .303 British caliber, the Lewis guns reportedly performed well in the Mexican campaign, especially compared to the flawed M1909 Benet-Mercie machine rifle.

The United States’ declaration of war in April 1917 resulted in an immediate need for modern infantry arm for the rapidly expanding military. The U.S. Navy ordered 6,000 Lewis guns from Savage to arm landing parties, for shipboard duty and to equip the U.S. Marine Corps. The Navy Lewis was adopted as the “Model of 1917” and chambered for the standard M1906 (.30-’06 Sprg.) cartridge. Except for minor dimensional variances due to differences between the .30-’06 and .303 cartridges and different types of bipods, the M1917 Lewis was very similar to the British version.

Shortly after the U.S. Navy contract, the U.S. Army reluctantly reconsidered the issue and placed an order for 2,500 M1917 Lewis guns from Savage. The Army, however, made it clear the guns would only be authorized for training use. The U.S. Marine Corps, on the other hand, became an enthusiastic supporter of the Lewis. A USMC Lewis Machine Gun School was organized at the Savage Arms plant to train Marine armorers.

In addition to use as an infantry arm, the Lewis machine gun became popular as aircraft armament due to its reliability and ease of changing magazines as compared to typical machine gun belts. The standard ground-model Lewis could be easily converted to aircraft use by replacing the wooden buttstock with spade grips and removing the barrel radiator. A 97-round magazine was developed for aircraft use.

When the Marines deployed to France, they carried along their trusty M1917 Lewis guns. Upon arrival, however, the Marines were dismayed when informed by the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) that they would have to relinquish their Lewis guns to be replaced by woeful French Chauchat machine rifles. The stated reason was uniformity in arms, but this explanation didn’t go over very well with the combat Marines who were extremely unhappy about being forced to exchange a familiar and reliable arm for the notably unreliable French designs. As related in the book History of the United States Marine Corps: “The Marines … turned in their trusted Lewis machine guns in exchange for French Chauchat automatic rifles and Hotchkiss machine guns, both heavy and unreliable weapons that used different ammunition from the Marines’ Springfields, and thus complicated supply problems.”

The U.S. Army Doughboys who had trained stateside with Lewis guns were also displeased with having to leave them behind, but were generally less vocal than the Marines. Some U.S. troops were temporarily assigned to British units and had the opportunity to utilize .303 Lewis guns in combat. Otherwise, in marked contrast to the British and Belgians, combat use of Lewis guns in World War I by U.S. troops was essentially non-existent. Many of the ground-model Lewis guns were diverted to the U.S. Army Air Service and converted to aircraft use.

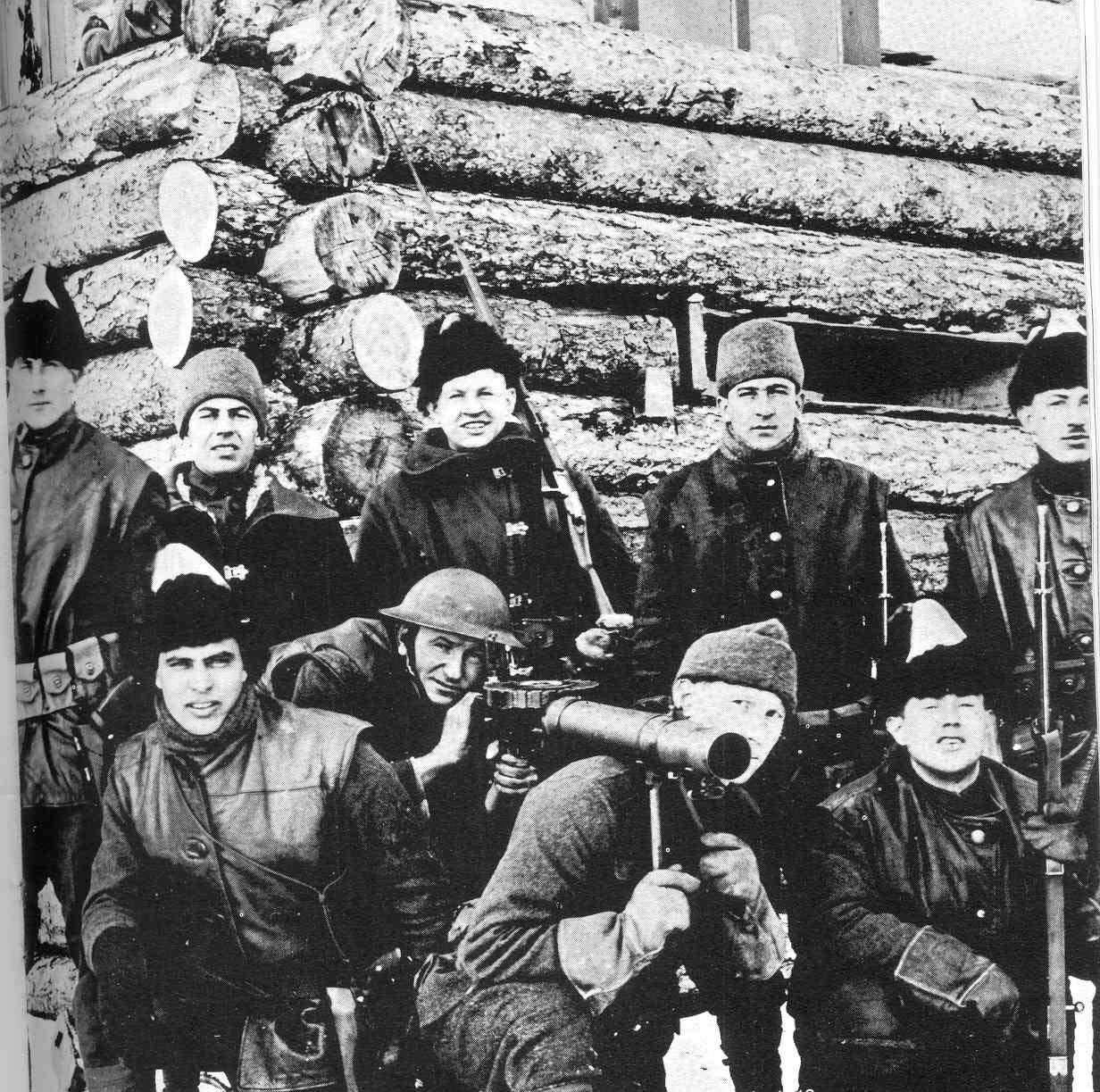

After the Armistice, the Lewis was all but abandoned by the U.S. Army, although a few were used in the ill-fated North Russian intervention in the immediate post-World War I period. On the other hand, the U.S. Marine Corps and U.S. Navy retained their Lewis guns, and they saw a surprising amount of combat use between the wars in the hands of Marines and sailors in varying locations around the globe. Lewis guns were part of the armament of the U.S. Navy gunboats plying the Yangtze River protecting American interests in China in the 1920s and 1930s. Marines used their Savage M1917 .30-’06 Lewis guns in a number of small-scale, but often bloody, combat actions in several Caribbean and Central America locales, including Haiti and Nicaragua. The Lewis performed well during in such engagements and provided a much-needed edge to our often-undermanned Marines.

In addition to being used by the United States in the 1920s and 1930s, the Lewis was a mainstay in British service until it was replaced by the more advanced Bren light machine gun beginning in 1935. Nevertheless, many of the Mark I .303 Lewis guns lingered in Great Britain’s arsenals and saw use well into World War II. The Japanese adopted the Lewis gun in 1929, and relatively large numbers were used in World War II by the Japanese navy, primarily for aircraft armament. Most of the Japanese Lewis guns were made by the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal. It is not widely known that Norway also manufactured and utilized limited numbers of Lewis guns in the 1930s.

By World War II, the Lewis was relegated to a second-tier arm in U.S. service. The Marines had replaced their Lewis guns in front-line service with other guns, including the M1919A4 air-cooled machine gun. But a surprising number of M1917 Lewis guns remained in use during World War II, primarily by the United States Navy as secondary armament on landing ships and other vessels.

Any thought that the Lewis gun was incapable of providing valuable service during this period can be easily dispelled by noting that the only U.S. Coastguardsman to be awarded the Medal of Honor, Douglas A. Munro, utilized the Lewis gun in World War II during a heroic engagement off Point Cruz, Guadalcanal, on September 27, 1942.

Even though the Lewis performed yeoman-like service as late as World War II, it was clearly an obsolescent arm and its glory days were long-past. During its prime, the Lewis gun was the best of its type available, as evidenced by its performance in the Great War in the hands of our British and Belgian allies. It is unfortunate, and more than a little ironic given its homegrown pedigree, that our Doughboys and Marines were denied the ability to take the Lewis into battle in World War I. If they had, it is certain the American version of the “Belgian Rattlesnake” would have bitten a lot more of the enemy!

The .45 Colt cartridge is a wonderful relic of days gone by. Conceived in the immediate post-Civil War era, the old slugger first sent that half-ounce slug lumbering downrange some 144 years past. It served the nation well in the Indian Wars and in the difficulties in the Philippines. Unofficially, it has served police officers from the New York State Troopers to Santa Ana PD. The salient feature of the round was always brute power, a quaint old belief that someone who deserves to be shot deserves to be proper shot. The .45 Colt bullet was massive, the velocity moderate, the effect monumental. Nearly a century and a half later, the .45 Colt—with proper ammo—is as good as you can get when it comes to a combat cartridge. And yes, I am aware that it is exclusively a revolver cartridge.

This was the cartridge that was most commonly loaded at home in recent years. It needed to be, because the available .45 Colt guns had not kept pace with the improvements in ammo. The last DA/SA Colt revolver was the much-lamented Colt New Service, which went out of print in 1942. Smith & Wesson delighted the big bullet boys by introducing the Model 25-5 in the late 1970s. That big N-frame got a fair amount of attention, but not enough to sell in the numbers that keep guns in their builder’s catalogs. So the .45 Colt cartridge hung on for use in the venerable Peacemaker and its clones. These guns simply will not prosper on a regular diet of high-pressure, hig- velocity, heavy-bullet ammo. In reality, the big S&Ws don’t do very much better. The makers of modern commercial ammunition are aware of these limitations, so they will never load high-performance ammunition in .45 Colt. Understandably, the big makers are afraid of serious liability issues when they make high pressure ammo that fits a gun which is identified as being that caliber.

Does this mean that the .45 Colt is commercially dead? Absolutely not! There are large numbers of very strong revolvers that will handle high performance .45 Colt handloads. They are, in effect, .45 Magnums. This fact has long been accepted among the handloading fraternity and the loading manuals often list special loads just for these guns. For decades, the strong Ruger Blackhawks have been loaded to the firewall and stay accurate. The big revolvers from Freedom Arms are even stronger. If you really need super performance in a portable handgun, you might want to consider one of the big Freedoms in .454 Casull.

This situation suggests that the .45 Colt is “two-faced” in the sense that it has two useful natures. One is ammo with traditional performance—big bullet, low-velocity—or anything that says “.45 Colt” on the barrel. The other is ammo put up in brass marked .45 Colt, for use in selected guns of known strength by advanced handloaders who are experienced and extremely cautious.