![r/WarshipPorn - Graphic of the Royal Navy during WW2 with the ships in red the ones that were sunk - Truly incredible to see the scale of their force [2744 × 1398]](https://preview.redd.it/8esdcgt9lfx71.jpg?width=960&crop=smart&auto=webp&s=9eebf6d299dc3455aaf5d4c7b47df315cc837f9f) The ones in Red were sunk during WWII

The ones in Red were sunk during WWII

![r/WarshipPorn - Graphic of the Royal Navy during WW2 with the ships in red the ones that were sunk - Truly incredible to see the scale of their force [2744 × 1398]](https://preview.redd.it/8esdcgt9lfx71.jpg?width=960&crop=smart&auto=webp&s=9eebf6d299dc3455aaf5d4c7b47df315cc837f9f) The ones in Red were sunk during WWII

The ones in Red were sunk during WWII

It was one of the most epic manhunts in American history, and it required arguably the greatest lawman of the 20th Century to finally bring it to a successful conclusion—Frank Hamer.

For several years during the Great Depression of the 1930s, Clyde Barrow and his girlfriend Bonnie Parker and their gang terrorized small towns across the Midwest and Southwest. Robbing numerous banks, grocery stores and rural gas stations, they ranged from New Mexico to Indiana and from Minnesota to Louisiana, murdering nine men in the process, six of whom were law enforcement officers.

The bold Barrow Gang seemed to have little trouble evading capture. Following a robbery, they thought nothing of driving 1,000 miles or more at high speeds across multiple state lines, preferring large cars such as the Ford four-door sedan with a powerful V-8 engine under the hood as getaway vehicles. Not surprisingly, they obtained those cars by stealing them.

When confronted by police, who were usually armed only with six-shot .38-caliber service revolvers, Bonnie and Clyde responded with overwhelming firepower: automatic and semi-automatic rifles, shotguns filled with buckshot and .45-caliber semiautomatic handguns. Clyde’s weapon of choice was the BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle), which fired devastating rounds of .30-06 ammunition. Barrow obtained the BARs and high-powered handguns by breaking into National Guard armories.

Ironically, Frank Hamer was no longer a Texas Ranger when he was asked to track down Bonnie and Clyde. Retired after a long and illustrious career with the Rangers in which he had risen to the rank of captain, Hamer was credited with bringing many outlaws to justice in the Lone Star State. He was also known for having killed numerous men in the line of duty—some sources say as many as 53. For his pursuit of Bonnie and Clyde, Hamer would be paid $180 per month and hold the title of Special Investigator.

He began his investigation in early February 1934 by learning as much as he could about the Barrow Gang. “It was necessary for me to make a close study of Barrow’s habits,” Hamer said. “An officer must know the mental habits of the outlaw, how he thinks, and how he will act in different situations.”

Hamer soon learned that Bonnie and Clyde’s life on the run was anything but glamorous, despite all their stolen money. The couple had become so notorious that they often had to lay low by sleeping in their car and bathing in creeks, eating whatever they could find. In addition, the pair argued incessantly, with Clyde occasionally beating Bonnie.

Captain Hamer eventually discovered that the gang ran a somewhat circular route from Dallas, Texas, to Joplin, Missouri, to Shreveport, Louisiana, then back to Dallas. He also learned that a career criminal by the name of Henry Methvin was now occasionally a member of the gang. Hamer reasoned that if he could somehow locate Methvin, Methvin might lead him to Bonnie and Clyde.

The break in the case came when Henry Methvin’s father, Ivy Methvin, came to the realization that it was only a matter of time until his son was captured or killed as a result of running with the Barrow Gang. Ready to make a deal, he let it be known to local law enforcement that he would finger Bonnie and Clyde if his son Henry was given immunity from prosecution. It didn’t take long for Hamer get the word and agree to the arrangement.

The Barrow Gang visited the Ivy Methvin home every few weeks to rest and recuperate for a few days, so officers told Ivy to let them know when Bonnie and Clyde were next due. Hamer finally got that long-awaited phone call on the evening of May 22, 1934; he and five other veteran lawmen immediately sprang into action.

The officers set up an ambush in some pines and brush along a rural road near Gibsland, Louisiana, along the route Bonnie and Clyde were expected to take. Ivy Methvin had been instructed to park his truck along the berm on the far side of the road in front of the hidden officers and remove one of the truck’s wheels. It was hoped that when Bonnie and Clyde approached the truck they would recognize it and stop to see if Ivy needed assistance. It was then that Captain Frank Hamer and his posse would effect the arrest. The plan was to take Bonnie and Clyde alive, if possible.

The ruse worked to perfection…almost. At about 9:15 a.m. on that fateful May morning, as Bonnie and Clyde’s car approached Ivy Methvin’s parked truck, a large, slow-moving logging truck was suddenly seen approaching from the opposite direction. Would the log truck inadvertently pull between the gangsters’ car and the hidden officers, blocking their view and field of fire?

The officers did not allow that to happen. As soon as Bonnie and Clyde’s vehicle was within range the officers opened up with fully-automatic and semi-automatic weapons, pumping a total of 167 bullets and buckshot into Bonnie and Clyde’s car. Bonnie was hit at least 41 times, Clyde 17 or more, the driver’s-side door protecting Clyde somewhat. Both outlaws died instantly. Thus ended the lives of the infamous outlaws Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker.

Found in their car was the suspected arsenal of weapons: two BARs, nine Colt semi-automatic pistol, and one revolver—all loaded. Three bags and a box held more than 2,000 rounds of ammunition. On the floor was a valise containing 40 BAR magazines, fully loaded with 20 rounds each. In addition there were 15 car license plates, stolen from various states.

As a result of his relentless, expert detective work, Captain Frank Hamer was hailed as a national hero, and rightly so. However, that national image of the lawman was not to last. In 1967, 12 years after Hamer’s death as a result of a heart attack, Warner Brothers studios in Hollywood released the film Bonnie and Clyde. Starring Warren Beatty as Clyde and Faye Dunaway as Bonnie, the film won two Academy Awards.

Unfortunately, the movie was a highly-fictionalized account of the actual true story, portraying Captain Frank Hamer as the villain. Hamer’s wife, Gladys, was so incensed that she sued Warner Brothers for defamation, invasion of privacy and unauthorized use of Frank Hamer’s name. She received $20,000 from the studios as a settlement, a large sum of money at the time.

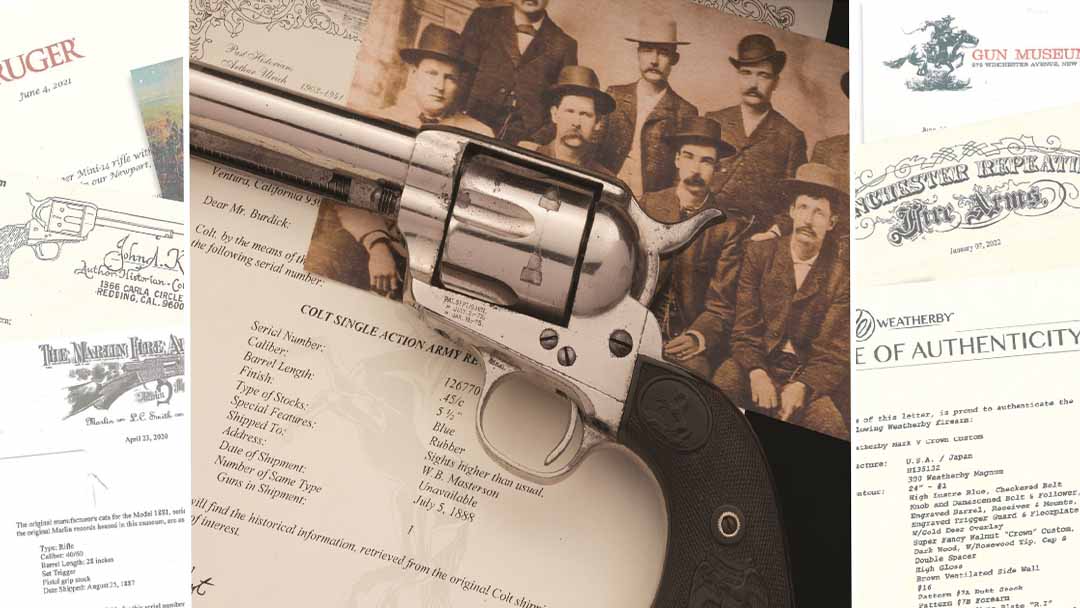

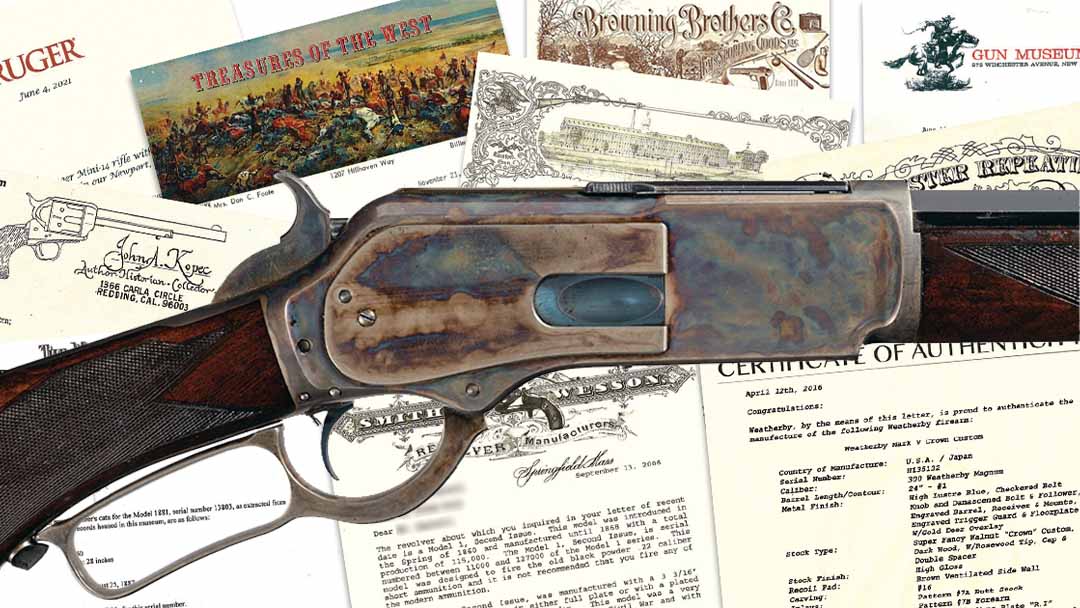

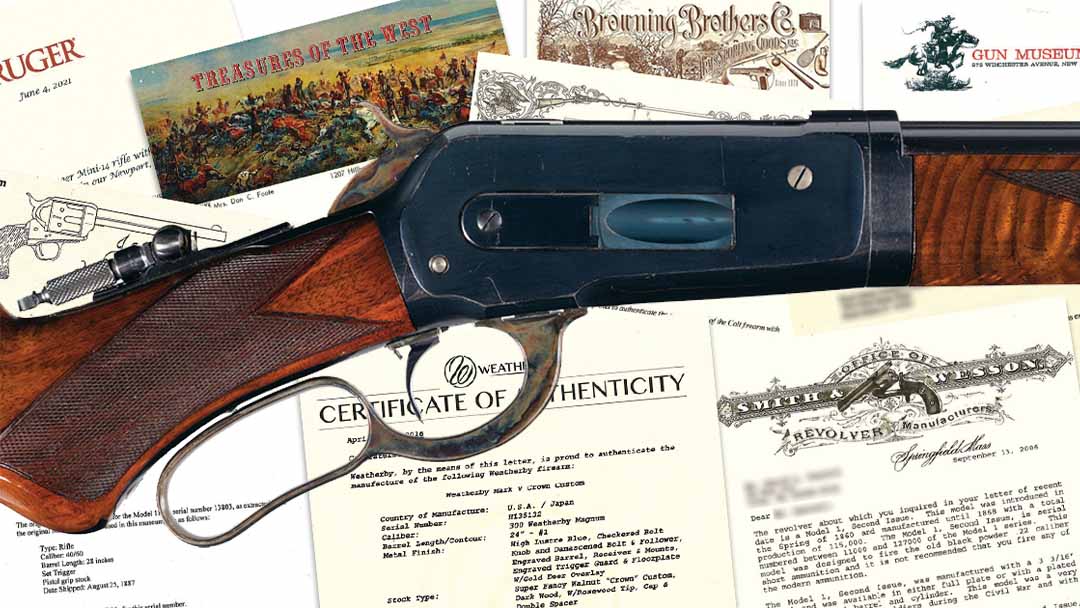

Hey there, wait a minute Mister Postman. Is there value in that factory letter?

The debate over the value of a “factory letter” is one that seems to pop up from time to time in gun forums. So what is the answer?

Model, condition, finish, grips, engraving, where it was shipped, to whom it was shipped, and serial number range are all considered in determining an old gun’s value. A letter can help answer some of those questions.

In Rock Island Auction Company’s recently completed Premier Auction, factory letters from a number of gun manufacturers like Colt, Ruger, Smith & Wesson, and Browning were provided. Buffalo Bill Center of the West has records for a number of long gun makers like Winchester, Marlin, and Ithaca, and many of those factory letters were also provided at auction. Private authenticators like John Kopec also lend their expertise with documentation.

Those who don’t see the value likely aren’t concerned about the collectability of a gun or don’t want to get bad news. Those who do get letters see the value of an antique gun as a piece of history and want to know its heritage. How did it leave the factory and where did it go?

The cost of a letter — ranging from $10 to $350 — is often seen as adding value to an already valuable gun.

At the very least, a factory letter or an authentication letter from a respected researcher can provide basic shipping information on where it went, when it left the factory, a basic description of the gun, and any special features like grips and finish. A factory-lettered firearm likely will have the document displayed with it at a gun show.

Not only does it help the owner in setting a price, but it can also lend confidence to a buyer by offering authenticating documents as to what they are buying.

In 2021, Rock Island Auction Company sold a Colt Single Action Army owned by gunslinger and sportswriter Bat Masterson. Documentation accompanying the revolver included a letter from Colt Manufacturing confirming it was shipped to Masterson with a higher front sight as requested. However, the gunfighter asked for nickel plating and the letter incorrectly states it was shipped with a blued finish. Follow-up documentation confirms the incorrect finish listed on the factory letter. The gun sold for $488,750.

This May, RIAC offered a Colt Single Action Army that was reportedly recovered from the Little Bighorn battlefield. A letter from highly-respected Colt researcher John Kopec showed it was one digit away from the serial number of a Colt SAA recovered from the Little Bighorn battlefield in 1992. It also described the gun as a significant “Custer-Era” “Lot-Five” revolver while also noting the blemishes on the 150-year-old wheel gun. The revolver sold for $763,750.

Rock Island Auction sees a number of factory letters each year, especially with Colt Single Action Army revolvers. Not all of them are sent to Bat Masterson, but some collectors are interested in where guns were shipped, especially to the west, before territories like New Mexico, Arizona, and Alaska achieved statehood.

A commenter on the Colt forum wrote that anyone who owns a Single Action Army that was made before World War II should get a factory letter for it. First generation Single Action Army revolvers were made until 1941.

The first step for someone wanting to assess the true gun value is to check the “Blue Book of Gun Values,” which will provide an amount without consideration of its history.

Experts say that documentation can be helpful in assessing gun prices, but that sometimes there is no tangible evidence tying a gun to a historic person, place, or event.

Guns with a military or law enforcement pedigree may be attractive to some buyers, so a factory letter can often provide information on whether it was shipped for military or police use. Experts recommend always confirming a factory letter, saying “Paper is generally easier to forge than steel.”

The NRA Museum website reports that documentation — and especially the type of documentation — can make a difference in valuing a weapon. Masterson’s revolver is an example of that. The finish was recorded incorrectly in the factory letter, but follow-up documents confirm what Masterson requested.

Remember, the letter provides information on where and to whom it was shipped, and what features it had when it went out the door. Those things are of interest to collectors and can contribute to the value of a prized family heirloom or inherited gun.

The history of a gun and who owned it can weigh heavily on its value. Historical significance and the credibility of the information are the biggest factors in historic attribution. Here is an example: A factory letter might show that a revolver was shipped to a certain western outlaw. It doesn’t confirm the current owner’s affidavit that years ago a deputy marshal gave the outlaw’s gun to the owner’s great great grandfather.

Skepticism must rule with historical attribution, but a factory letter can help bring ownership or chain of ownership into focus. On the other hand, it can also protect the potential buyer from ending up with a forgery.

Experts recommend being very detailed in a record request for a factory letter. The more information on what is being sought in a request, the more likely researchers can find something interesting ̶ if it’s there to be found.

Commenters on various forums acknowledge that a factory letter is at least a good starting point for research into a gun’s history.

Self-education is the best thing a collector can do to avoid getting hung with something that might not be what is professed. A serious gun seller might also consider a free gun assessment with Rock Island Auction Company if they are considering gun consignment. Talk to other collectors and learn about the gun type that interests you most.

The recently-completed premier auction had more than 100 lots that included descriptions specifically stating that some type of authenticating letter or research was included. These are guns without the flash of Ulysses S. Grant’s revolvers (that came with plenty of authenticating documents, too), but just nice, collectible Colts, Winchesters, Marlins, and Smith & Wessons.

A factory letter or an authentication letter may not be necessary for the collector keeping a gun for themselves, but if you are curious about a weapon’s history or are planning on selling your gun, most commenters in the various forums recommend a factory letter. When a collectible firearm changes hands, documentation can provide value, but also offer peace of mind.