In Mary Shelley’s timeless novel, Dr. Frankenstein created his eponymous monster from body parts stolen from the grave and reanimated. Shooters have been known to do something similar, though the parts don’t necessarily come from no-longer-functional donors and often work out better for all concerned than Dr. Frankenstein’s creation.

Let me share with you some “Frankenguns” of my acquaintance that worked out just fine.

Revolvers

In the early days of “police combat” revolver competition, the 6″ barrel .38 was the max you could use. Colt versus S&W was the handgun world’s version of Ford versus Chevy or Coke versus Pepsi and it was the Colt’s slightly greater accuracy versus the Smith & Wesson’s more “even” one-stage double-action pull. The Colt Python’s barrel tapered a thousandth of an inch toward the muzzle, driving the lead bullet tighter into the rifling grooves, which on the Colt were a 1:14″ twist compared to the Smith’s 1:18.75. The Colt seemed to better stabilize 148- to 158-gr. lead slugs.

Gun-savvy cops were grateful when Bill Davis, late of the California Highway Patrol, pioneered the concept of putting a Python barrel on a K-Frame S&W. The result, known variously as a “Smolt” and a “Smython,” combined the best of both brands. The NRA managed PPC competition soon caught onto this and changed the rules. They required in Distinguished or Service Revolver competition, the gun had to have its barrel made by the same company that manufactured the gun. My own Davis Custom Smython, via my good friend Chuck McDonald, is a treasured part of my collection even though it was soon supplanted by “PPC guns” with monster Douglas and Apex barrels and mounting BoMar or Aristocrat sight ribs.

I came to own some of the latter, Frankenguns in their own right, made by legends like Ron Power and Andy Cannon. My single sweetest, though, may have been a pre-war Colt Official Police tuned to single-stage DA by master Python mechanic Reeves Jungkind. The massive barrel was an inch and a quarter under its Aristocrat rib, but it always put the bullets where I aimed them.

Autoloaders

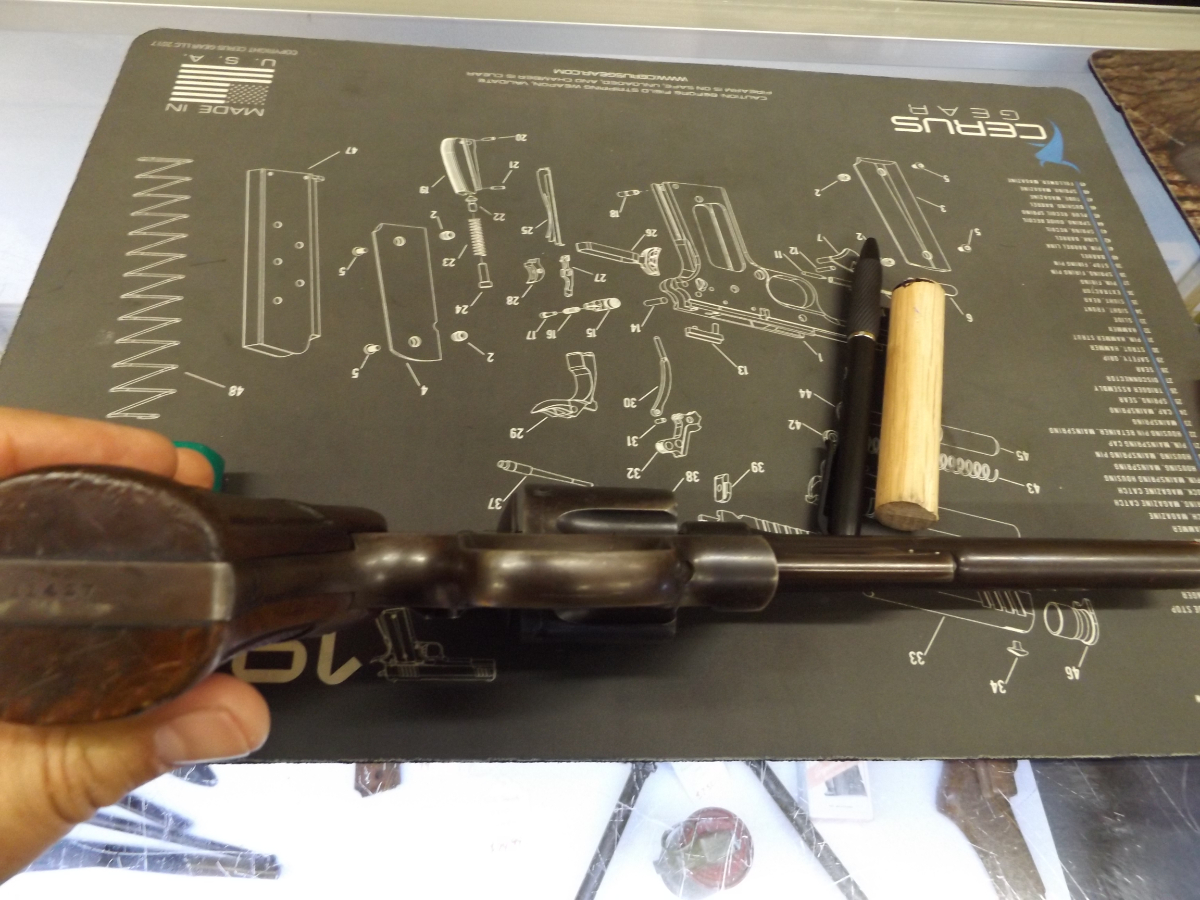

WWII hero Jim Clark Sr. became, in the early 1950s, the first and still the only civilian to win the National Pistol Championship in bullseye shooting without the benefit of having been funded by a military team. One of the great master gunsmiths, he was also the man credited with creating both the long-slide 1911 and a 1911 which could feed the blunt, rimmed .38 Special wadcutter revolver cartridge. An inch would be amputated from another 1911 slide to go onto the one of the chosen Colt .38 Super, a 6″ match grade .38 Special barrel would be enshrouded within and Jim would work his magic to make it all work with 100 percent reliability — not to mention a 2.5-lb. trigger pull.

By the time I could afford a Clark Custom long-slide, my bullseye days were long over but there were some PPC matches where it was allowed in Open Semi-Auto class. Mine won me a bunch of local PPC matches and also some falling plate shoots. It’s a most specialized piece of equipment, one of the finest firearms I own and I will always cherish it. Jim has left us, and just as sadly so has his son Jim Jr., but the family legacy of fine bespoke firearms lives on with his daughter Kay Clark-Miculek, his son-in-law Jerry Miculek, and the outstanding crew at Clark Custom.

A Special Gun

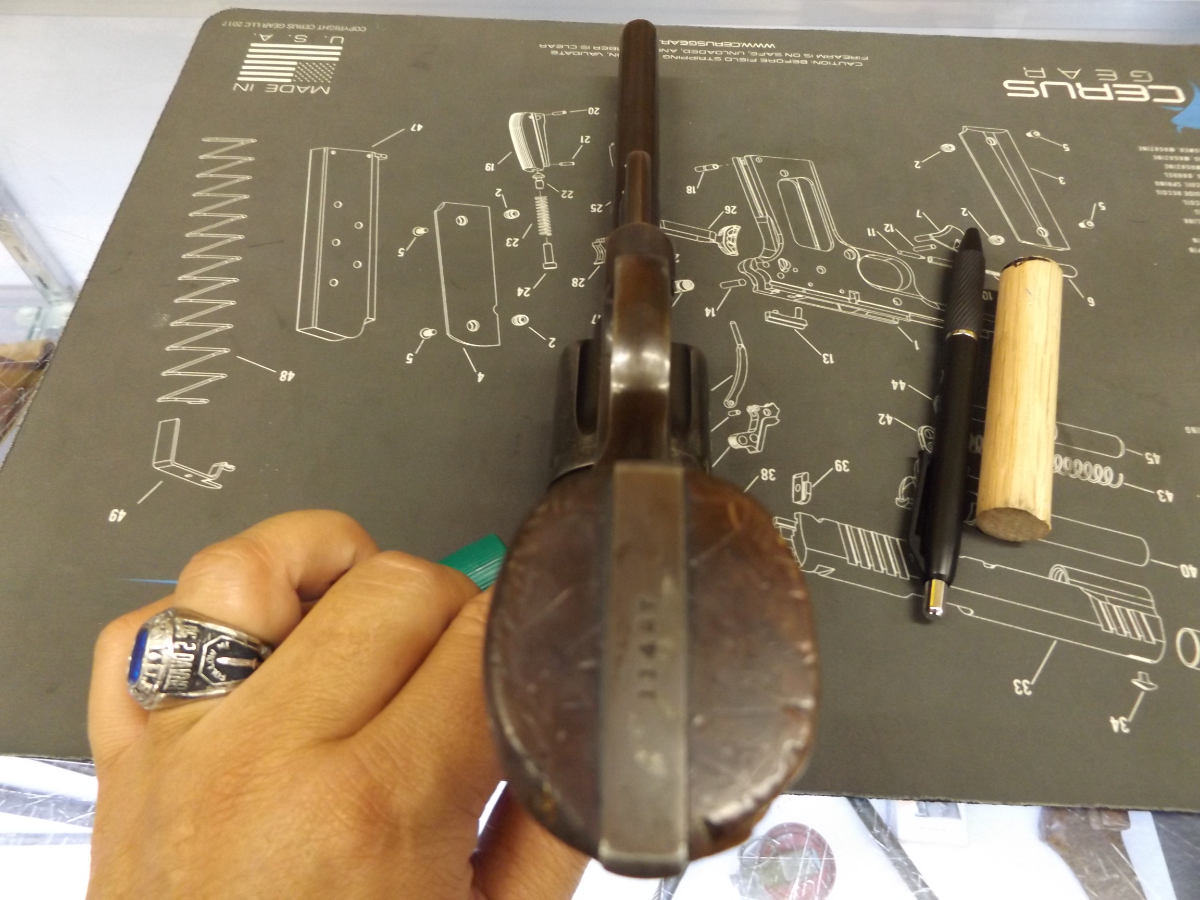

The first “Ayoob Special,” built by the late, great John Lawson in Tacoma, was kind of a Frankengun. I had bonded with my first Colt .45 auto, a 5″ GI surplus model, at age 12 in 1960. By the ’70s, I had discovered the 4.25″ all-steel Combat Commander balanced a little better for me but seemed to have a bit more muzzle jump. I installed a 5″ barrel in one, planning to have the exposed part of the barrel Mag-na-ported, but it turned out the barrel lugs weren’t compatible between the Government Model barrel and Commander slide, and it broke. I sent it to John, who installed a 5″ barrel properly fitted, and it went thence to Larry Kelly at Mag-na-port — sure enough, muzzle jump was less than with the longer, heavier Government. It later got a Bar-Sto barrel, also ported, to enhance accuracy. I have it still, a sweet reminder of what was then state-of-the-art in a carry and competition .45.

Mix and match: I can confirm from personal experience that, at least sometimes, the concept works — and we’ve only touched a tip of the Frankengun iceberg.

U.S. Army Rangers are elite warriors who must complete an intensive two-month training school to earn the coveted designation of Ranger. The training is so difficult and demanding, both physically and mentally, that only about half of those who begin a Ranger class successfully complete it—and several have literally died trying.

Other than the Rangers themselves, few people today realize that the training is based upon another group of elite warriors formed more than 250 years ago by Major Robert Rogers (1731-1795). An American colonial frontiersman, Rogers served in the British army during the French and Indian War, and it was during that war that he first trained and commanded his famous Rogers’ Rangers.

Initially, the rangers numbered only a handful of handpicked men who conducted scouting and spying missions. But as the successes of this small group grew and its fame spread, more and more likeminded backwoodsmen asked to join Rogers. Ultimately, he found himself commanding hundreds of troops, allowing him and his rangers to then engage not only in scouting and spying, but also major military offensives.

As a result of those many experiences, in 1757 Rogers developed his “28 Rules of Ranging.” Some of Rogers’ unwritten rules were simple, practical, and straightforward: Brown the barrel of your rifle so that no glint of metal will give you away to the enemy; cut the hair on your head short so that an enemy cannot grab it during hand-to-hand combat and jerk you off your feet; and wear green-colored outer clothing to better blend in with a woodland background.

Rogers’ written rules, however, were more detailed. The following are some edited excerpts of those 28 Rules, grouped under various headings, and appearing as they did in their original form:

Equipment: All Rangers are to be subject to the rules and articles of war…equipped with a firelock, sixty rounds of powder and ball, and a hatchet…so as to be ready on any emergency to march at a minute’s warning…

Marching: If your number be small, march in a single file, keeping at such a distance from each other as to prevent one shot from killing two men, sending one man, or more, forward, and the like on each side, at the distance of twenty yards…

Moving over marshy ground: If you march over marshes or soft ground…march abreast of each other to prevent the enemy from tracking you (as they would do if you marched in a single file) till you get over such ground…and march till it is quite dark before you encamp…on a piece of ground which may afford your sentries the advantage of seeing or hearing the enemy some considerable distance, keeping one half of your whole party awake alternately through the night.

Taking prisoners: If you…take any prisoners, keep them separate till they are examined, and in your return take a different route from that in which you went out, that you may the better discover any party in your rear, and if their strength be superior to yours, to alter your course, or disperse, as circumstances may require.

Moving as a body: If you march in a large body of three or four hundred…divide your party into three columns…and let those columns march in single files, the columns to the right and left keeping at twenty yards distance or more from that of the center…and let proper guards be kept in the front and rear, and suitable flanking parties at a due distance…with orders to halt on all eminences, to take a view of the surrounding ground, to prevent your being ambuscaded…

Taking and returning fire: If you…receive the enemy’s fire, fall, or squat down, till it is over; then rise and discharge at them…advance from tree to tree, with one half of the party before the other ten or twelve yards. If the enemy push upon you, let your front fire and fall down, and then let your rear advance through them…by which time those who before were in front will be ready to discharge again, and repeat the same alternately…by this means you will keep up such a constant fire that the enemy will not be able easily to break your order, or gain your ground.

Take care when pursuing a retreating enemy: If you oblige the enemy to retreat, be careful in your pursuit of them to keep out your flanking parties, and prevent them from gaining eminences, or rising grounds, in which case they would perhaps be able to rally and repulse you in their turn.

If you retreat: If you are obliged to retreat, let the front of your whole party fire and fall back, till the rear hath done the same, making for the best ground you can; by this means you will oblige the enemy to pursue you…in the face of a constant fire.

Upon becoming surrounded: If the enemy is so superior that you are in danger of being surrounded…let the whole body disperse, and every one take a different road to the place of rendezvous…but if you should happen to be actually surrounded, form yourselves into a square, or if in the woods, a circle is best, and, if possible, make a stand till the darkness of the night favors your escape.

When to fire: In general, when pushed upon by the enemy, reserve your fire till they approach very near, which will then put them into the greatest surprise and consternation, and give you an opportunity of rushing upon them with your hatchets and cutlasses to the better advantage.

Repulsing Indian attacks: At the first dawn of day, awake your whole detachment; that being the time when the savages choose to fall upon their enemies, you should by all means be in readiness to receive them.

Attacking a superior enemy: If the enemy should be discovered by your detachments in the morning, and their numbers are superior to yours, and a victory doubtful, you should not attack them till the evening, as then they will not know your numbers, and if you are repulsed, your retreat will be favored by the darkness of the night.

Prior to leaving camp: Before you leave your encampment, send out small parties to scout round it, to see if there be any appearance or track of an enemy that might have been near you during the night.

When taking a break: When you stop for refreshment, choose some spring or rivulet if you can, and dispose your party so as not to be surprised, posting proper guards and sentries at a due distance, and let a small party waylay the path you came in, lest the enemy should be pursuing.

Crossing rivers: If, in your return, you have to cross rivers, avoid the usual fords as much as possible, lest the enemy should have discovered, and be there expecting you.

Passing lakes: If you have to pass by lakes, keep at some distance from the edge of the water, lest, in case of an ambuscade or an attack from the enemy…your retreat should be cut off.

Watch your back: If the enemy pursue your rear, take a circle till you come to your own tracks, and there form an ambuscade to receive them, and give them the first fire.

When returning to a fort: When you return from a scout, and come near our forts, avoid the usual roads, and avenues thereto, lest the enemy should have headed you, and lay in ambush to receive you, when almost exhausted with fatigues.

Setting an ambush: When you pursue any party that has been near our forts or encampments, follow not directly in their tracks, lest they should be discovered by their rear guards, who, at such a time, would be most alert; but endeavor, by a different route, to head and meet them in some narrow pass, or lay in ambush to receive them when and where they least expect it.

When and how to travel by water: If you are to embark in canoes, batteaux, or otherwise, by water, choose the evening for the time of your embarkation, as you will then have the whole night before you to pass undiscovered by any parties of the enemy, on hills, or other places, which command a prospect of the lake or river you are upon. In paddling or rowing, give orders that the boat or canoe next the stern-most, wait for her, and the third for the second, and the fourth for the third, and so on, to prevent separation, and that you may be ready to assist each other on any emergency.

Attacking near rivers or lakes: If you find the enemy encamped near the banks of a river or lake, which you imagine they will attempt to cross for their security upon being attacked, leave a detachment of your party on the opposite shore to receive them, while, with the remainder, you surprise them, having them between you and the lake or river.

Final instructions: Whether you go by land or water, give out parole and countersigns, in order to know one another in the dark, and likewise appoint a station every man to repair to, in case of any accident that may separate you.

If you’d like to read the list of Major Robert Rogers’ “28 Rules of Ranging” in its entirety, click here: http://www.rogersrangers.org/rules/index.html.

.gif)

.gif)

.jpg)

New DSA G-Series Clone FAL Rifle