Inland M1 Carbine Range 2

The oldest son of Léon Constant Ghislain Carton de Wiart and his wife Ernestine Wenzig, Adrian Carton de Wiart was born on May 5, 1880, in Brussels, Belgium. Carton de Wiart was raised in a world of privilege, but he was never soft. Rumors swirled during his childhood that the young man was actually the illegitimate son of Belgian King Leopold II. As the child matured his time was split between Belgium and England.

When Adrian was six his parents divorced. His mother married Demosthenes Gregory Cuppa later that same year. This fact has no bearing on the story. I simply thought Demosthenes was one of the coolest names I had ever heard. After the divorce, Adrian’s father moved with him to Cairo. There he learned to speak Arabic.

Adrian’s father remarried, and the boy was dispatched to an English boarding school. This was considered de rigueur for young men of means during this time. He ultimately found himself at Balliol College in Oxford. However, in 1899 Carton de Wiart dropped out of school to go to war.

In a familiar refrain, Adrian lied about his age to get into uniform. In short order, he found himself in South Africa during the Second Boer War. In all the excitement of enlisting, training, and deploying to an active war zone, Adrian neglected to notify his father that he had joined the military. Soon after his arrival in Africa, he was wounded in the groin and belly and evacuated back to England. When his father found out that Adrian had left Oxford to fight in Africa he was livid. Adrian returned to Oxford after he recovered, but this didn’t last, either.

Soldiering was in his blood, and Carton de Wiart sought out chaos. He was granted a commission in the Second Imperial Light Horse and in 1901 made his way back to South Africa. The following year he was posted to India. While there he became enamored with the fine art of pig-sticking.

A Curiously Horrible Hobby

Pig sticking was popular among young British Army officers with more balls than brains. The Indian boar was known as the Andamanese pig and stood roughly three feet at the shoulder. Heavily tusked, these rangy animals topped out at around 300 pounds. Pig stickers took these ghastly beasts with long boar spears. These spears included a rigid cross guard to keep the enraged porker from sliding up the spear once he was pithed to rip the hunter’s heart out with his dying breath.

Of pig-sticking and young soldiers, an unknown military official of the era had this to say, “A startled or angry wild boar is…a desperate fighter [and therefore] the pig-sticker must possess a good eye, a steady hand, a firm seat, a cool head, and a courageous heart.”

I actually know a petite young lady in my modest little Southern town who likes to hunt wild pigs with dogs and a big honking knife. In a crowd, you would take her for a cheerleader. However, she is obviously insane.

Much like his American doppelganger, Theodore Roosevelt, Carton de Wiart viewed physical setbacks as fuel for personal improvement. In the wake of his battlefield injuries, he embraced physical fitness as a remedy for lurking weakness. Though an inveterate gentleman around the ladies, he was also known for his coarse diction when it was just guys. He was later described as, “A delightful character who must hold the world record for bad language.”

In 1908 he married the Countess Friederike Maria Karoline Henriette Rosa Sabina Franziska Fugger von Babenhausen. Once again, there’s no real point to including her here beyond the obvious observation that hers was an absolutely epic name. Together they had two daughters. Imagine having to ask this guy permission to date his little girl…

At the outset of the First World War, Carton de Wiart was posted to British Somaliland to face the Dervish leader Mohammad bin Abdullah. History has come to refer to this character as the “Mad Mullah.” While serving in the Somaliland Camel Corps, Adrian was shot twice in the face. These injuries cost him his left eye and part of his ear. If you’re counting, that should be four major wounds thus far. In 1915 he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

After having been shot in the gut, the groin, and the ear and earning a handsome eye patch in lieu of an actual left eye, most combat veterans married to a wealthy Countess would rightfully retire to the family estate to draft their memoirs. By contrast, as soon as he could travel, Carton de Wiart caught a handy steamer for France and the largest war the world had ever seen.

Carton de Wiart commanded three separate infantry battalions and later a brigade. He caught bullets in his ankle and skull during the Battle of Cambrai. At the Battle of Passchendaele, he was shot in the hip and then later in the leg. At Arras, he took yet another round to the ear. He was wounded on seven separate occasions after he got to France.

In 1915 Adrian was shot in the left hand and duly reported to the unit surgeon. His hand was in quite a state, so de Wiart demanded the physician amputate his fingers so he could get back to the war. When the doctor refused the exasperated officer simply tore them off himself.

Carton de Wiart got his brigade a mere three days before the end of the war. Upon his arrival at his new command, the war-weary unit fell in for inspection. A man who was there said this of their new commander’s general demeanor, “Shivers went down the back of everyone in the brigade, for he had an unsurpassed record as a fire eater, missing no chance of throwing the men under his command into whatever fighting happened to be going…He arrived on a lively cob with his cap tilted at a rakish angle and a shade over the place where one of his eyes had been.”

The observer reported that the newly-minted brigadier was also missing a limb and had eleven wound stripes on his uniform. The first man in line for inspection noted that Carton de Wiart, despite having only one eye, ordered him to get his bootlace changed.

While a Lieutenant Colonel commanding the 8th Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment in 1916, Carton de Wiart earned the Victoria Cross, his nation’s highest award for bravery in combat. His citation reads, “For most conspicuous bravery, coolness and determination during severe operations of a prolonged nature. It was owing in a great measure to his dauntless courage and inspiring example that a serious reverse was averted. He displayed the utmost energy and courage in forcing our attack home. After three other battalion Commanders had become casualties, he controlled their commands, and ensured that the ground won was maintained at all costs. He frequently exposed himself in the organization of positions and of supplies, passing unflinchingly through fire barrage of the most intense nature. His gallantry was inspiring to all.”

We’re Just Getting Warmed Up

After the war, Carton de Wiart was posted to Poland as part of the British-Poland Military Mission. Poland was at that time in conflict with the Russians, the Lithuanians, the Ukrainians, and the Czechs. Throughout his time in Poland, de Wiart faced peril aplenty. In 1920 while out on an observation train his party was attacked by Red Army cavalry. De Wiart posted himself on the footplate of the train and repelled the mounted troopers with his revolver. At one point he fell off of the moving train only to quickly reboard. You recall that throughout it all the man only had the one hand and a single eye.

Carton de Wiart retired in December of 1923 to the estate of a Polish friend in the Pripet Marshes. Of the next period of his life, he later said, “In my fifteen years in the marshes I did not waste one day without hunting.”

In the summer of 1939 with the Nazis preparing to invade, de Wiart was recalled to active duty. When the Germans overran his estate they stole his fishing tackle, gun collection, furniture, and clothing. De Wiart narrowly escaped through Romania after an attack by the Luftwaffe that killed the wife of one of his aides. By now the old soldier was angry.

Carton de Wiart commanded Commonwealth forces during a running fight across Norway culminating in a desperate seaborne evacuation led by Lord Louis Mountbatten. Afterward, he briefly commanded a division in Northern Ireland before being dispatched to Yugoslavia as head of the British-Yugoslavian Military Mission. While en route in a Vickers Wellington bomber, the plane crashed into the sea about a mile short of Italian-controlled Libya. The 60-year-old, one-armed British Major General was knocked unconscious in the crash, but came to once doused in the cold water of the Mediterranean. He swam to shore but was captured by Italian forces on the beach.

During his subsequent incarceration as a POW, Major General de Wiart attempted to escape five times. One attempt to tunnel out of his camp occupied him for seven months. He once successfully remained loose for eight days disguised as an Italian peasant. This was all the more impressive considering he had only one arm, one eye, sundry obvious scars, and didn’t speak Italian.

Once the Italians decided they would abandon the Nazis they requested de Wiart serve as their emissary to the British Army. In this capacity, he needed fresh clothes and was sent to Rome at government expense for a fitting. Though he distrusted the Italian tailors, he said that he, “Had no objection provided he did not resemble a gigolo.”

We lack the space to do this man justice. After the Italian surrender, de Wiart was posted through China, India, and Egypt in a variety of official roles. Along the way, he was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

When passing through Rangoon, de Wiart tripped on a coconut mat and tumbled down stairs, fracturing several vertebrae in his back and rendering himself yet again unconscious. With a little time in a Burmese hospital he recovered. His first wife died in 1949. Two years later he married a woman 23 years his junior. Carton de Wiart finally retired for real to Aghinagh House in Killinardish, Ireland. He died in the summer of 1963 at the age of 83, a British hero of the sort about whom ballads are crafted.

On January 8, 2022, Aleksander Tarnawski turned 101 years old. 101 years prior he had entered the world kicking and screaming in Słocin in the Rzeszów poviat in Poland. At age seventeen, Tarnawski graduated from the gymnasium in Chorzów. He then enrolled in the University of Lviv studying Chemistry. The following year the entire world conflagrated.

Poland suffers from some of the most lamentable geography. Poland is on the way to any number of juicy geopolitical targets and has suffered from some of the most deplorably unneighborly neighbors. Like most of the young males of his generation, Aleksander Tarnawski soon found himself swept up in the war.

Tarnawski was not drafted in time to serve during the German invasion, but he was eventually arrested by the Soviet NKVD. At this time in this place, the NKVD didn’t need much of an excuse to arrest or even kill you. After presenting his documents from the University of Lviv he was ultimately released.

Tarnawski’s was the first generation of modern Poles to come of age in a free nation. When commenting on his mindset and that of his comrades he said this, “During my childhood and youth, after so many years of captivity, patriotism and the need to sacrifice oneself for the motherland were the main slogans. And if a young man like me grew up in such an atmosphere, it was as it is.”

Poland fell to Germany in 35 days. Their dedicated professional army was outnumbered by more than two to one. The overwhelming combat power of the Wehrmacht secured the nation on October 6, 1939. 874,700 Poles were hors de combat. 66,000 gave their lives in defense of their country…in 35 days. By comparison, we lost 58,000 troops in ten years’ worth of intense combat in Vietnam.

Traveling with a large number of refugees fleeing the Nazis, Aleksander Tarnawski made his way across the border to Hungary. After a stint in a Hungarian refugee camp, he crossed into France, where he reported to the WKU recruiting point. From there he was assigned to the 1st Infantry Regiment of the 1st Grenadier Division.

By now the Nazi blitzkrieg seemed irresistible. With the collapse of the Allied armies on the continent, Tarnawski was one of the lucky few to escape across the English Channel to Britain. Upon his arrival, the young man immediately began training to take the fight back to the Germans.

Once in Great Britain Tarnawski trained as an armor soldier. One day in mid-1943 he was approached by a Polish Colonel who asked if he would like to return to Poland. He explained, “I was 22 at the time, and secondly, there was a war all over the world, and I was sitting here idly, I agreed to go to Poland without hesitation.” Aleksander Tarnawski had just assessed into the Cichociemni.

The Cichociemni were the commandos of the Polish underground. The word roughly translates to, “The Silent Unseen.” Their mission was to infiltrate occupied Poland, coordinate and execute resistance operations, and kill Germans.

Drawn from all units of the Polish Armed Forces not under German subjugation, they knew they were volunteering for the most dangerous work of the war. Tarnawski trained in the art of close combat, silent killing, demolitions, covert communication, and spycraft under the tutelage of the British Special Operations Executive.

Tarnawski’s training included extensive physical fitness and the expert use of a wide variety of German, Russian, Polish, Italian, and British weapons. They trained to covertly emplace mines while learning cryptography, land navigation, and advanced marksmanship techniques. They learned about life in German-occupied Poland covering everything from curfews and military laws to contemporary fashion trends. Their hand-to-hand training was based on jujitsu.

Of 2,413 candidates, only 605 passed the training course. Among them were fifteen women. Of those, some 579 qualified for operational assignments. 344 of those trained operators were eventually deployed to Poland. 113 of these were ultimately killed in action.

On the night of April 16, 1944, Aleksander Tarnawski climbed aboard a four-engined Halifax bomber from the 300th Bomber Squadron at the Allied airbase in Brindisi, Italy, as part of Operation Weller 12 under Captain Edward Bohdanowicz. After an uneventful night combat insertion near the Polish village of Baniocha at Gora Kalwaria outside Warsaw, Tarnawski went to work. He was ultimately assigned to the Nowogródek District of the Home Army.

The Polish Home Army was designated the Armia Krajowa or AK for short. Their general mandate was to make life as miserable as possible for the German occupation forces. As the Soviet Red Army got closer to the Polish border the AK got more audacious in their combat operations.

This mandate was both incredibly complex and unimaginably dangerous. With support from the Cichociemni and Allied logistics, AK operatives conducted sabotage and direct action raids, emplaced mines, and established supply caches to support their sweeping insurgency efforts. The largest coordinated resistance operation of WW2 was the Warsaw Uprising that kicked off on August 1, 1944, under the direction of the AK. The Warsaw Uprising was part of the overarching Operation Tempest.

For sixty-three days Polish unconventional troops engaged in raging combat with German forces with little to no outside support. The Red Army had drawn up alongside the eastern suburbs of the city on Stalin’s orders and refused to assist the initiative. Stalin knew that the subjugation of Poland would be a necessary part of his post-war plans for conquest. Allowing the Germans to crush the Polish Home Army dovetailed perfectly into his dark schemes.

The Poles began the operation with nearly 49,000 men under arms. However, these were generally highly motivated but poorly trained irregulars armed with little more than a scrounged weapon and a handful of ammunition or a grenade. Arrayed against them were as many as 25,000 battle-hardened Wehrmacht and SS troops amply supplied and equipped with state of the art weapons.

During the course of the fight, the Poles employed two captured German Panther tanks, a Hetzer assault gun, and a pair of armored half-tracks. The Germans for their part had dozens of armored vehicles at their disposal along with Ju 87 Stuka dive bombers. The end result was a massacre.

More than 15,000 Polish resistance fighters died in the fight, while another 15,000 were captured. 5,660 Polish First Army soldiers became casualties. Balanced against that the Germans suffered as many as 17,000 killed or missing. There was as many as 200,000 civilian dead. Once the fighting abated the Germans came in and systematically leveled the city. The breadth of destruction precluded reliable numbers.

The Polish AK fought with whatever they could scrounge. They improvised armored vehicles out of civilian trucks and widely employed the Błyskawica submachine gun. A crude Sten-like weapon, the Błyskawica was the only standardized, mass-produced weapon to be built in occupied Europe during the war. The gun fired 9mm Para at around 600 rpm from a 32-round box magazine. Roughly 700 copies were built in underground workshops in Poland.

Throughout his time in occupied Poland, Aleksander Tarnawski undertook difficult and hazardous covert missions and also trained AK soldiers in the combat skills they needed to face the Germans. In slightly more than a year in combat Tarnawski earned the Polish Cross of Valor four times. He left the military as a Major.

The Rest of the Story

After the war, Tarnawski got a job with Polish Radio in Warsaw. Despite the chaos of active special operations service against the Nazis, he still retained his passion for Chemistry. He subsequently landed employment as a lab assistant in the Walenty Wawel coal mine in Ruda Slaska. From there, Tarnawski earned a Masters Degree in Chemical Engineering from the Silesian University of Technology.

Tarnawski eventually served as an assistant professor at the Institute of Non-Ferrous Metals in the 1960’s. He then earned a position as Senior Laboratory Engineer at the Institute of Plastics and Paints in Gliwice where he worked until he retired in 1994. Along the way he was married, widowed, and remarried, this time to a fellow Chemistry professor. Together they had a daughter who eventually earned her own PhD in Economics.

In September 2014, at age 94 at Książenice near Grodzisk Mazowiecki, fully seventy years after being dropped into Poland at night from a British Halifax bomber, Aleksander Tarnawski made one last parachute jump. This time he hit the silk with former and current GROM operators. GROM is short for Grupa Reagowania Operacyjno-Manewrowego which loosely translates to “Group for Operational Maneuvering Response.” I’m told this also means, “Thunder.”

Formally activated in 1990, GROM is one of five special operations units of the Polish Armed Forces and is respected around the world within the specops community. GROM is named in honor of the Silent Unseen of the WW2-era Polish Home Army. GROM operators are colloquially referred to as “The Surgeons” for their recognized capabilities at precision direct action operations.

As of January 2022, Major Tarnawski was the last survivor of those original 344 Cichociemni sent into combat during World War 2. After fighting the Germans undercover for more than a year and facing the likely prospect of torture and horrible gory death at any moment, Tarnawski went back to school and spent his entire professional life making the world a better place. He also saw to it that his daughter was educated and productive as well.

As amazing as his story was, Aleksander Tarnawski was typical of his generation. Those crusty old guys grew up with absolutely nothing and then faced literally unimaginable challenges. They not only prevailed in the face of such profound adversity but also thrived. Today’s crop of perennially-offended, easily-breakable social justice snowflakes would do well to learn from their example.

In all of American firearms history, there is no more legendary name than John Moses Browning. Born in 1855, he was not only an inventor and innovator, he was also a genuine gun genius. Browning made his first firearm at age 13 in his father’s gun shop, and was awarded the first of his 128 firearm patents in 1879 at just 24 years of age.

“John M. Browning is the unrivaled Dean of arms inventors and designers,” said Philip Schreier, director of NRA Museums. “Throughout the long history of firearms, from the year 1350 to the present, no one person has had such a staggering effect on the evolution of firearms technology as John Browning. Now, nearly 100 years after his death, most of his firearms designs and patents are still being used on a daily basis to defend life and liberty.”

Handgun: Colt Model 1911

This pistol takes its model number from the year Colt introduced it, 1911. And from then until 1984—over seven decades—it was the standard-issue sidearm for the entire U.S. Armed Forces, eventually replaced by the 9mm Beretta M9. Some modern versions of the gun are still in service with American military units, such as the U.S. Army Special Forces.

Browning developed the Model 1911 in response to the U.S. Army’s having sought a semiautomatic handgun to replace its outdated revolvers. His design won the highly competitive Army contract because the handgun was not only extremely reliable, but also had a number of unique attributes. For example, it was one of the first guns with parts that could be used to disassemble itself for simple, easy takedown and cleaning.

In addition to its military history, the Model 1911 is a very popular handgun with the general public yet today. An estimated 150 firearms manufacturers or more worldwide make and sell Model 1911-style handguns in various calibers. Compact variants of the gun are also in high demand as a concealed-carry gun because of the design’s relatively slim width and the stopping-power of the .45 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol) caliber.

Rifle: M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR)

An absolutely awesome battlefield weapon in terms of firepower, John Browning invented this rifle in 1917. As a result, it saw only limited use near the end of World War I, but extensive use during World War II and the Korean War. The BAR (short for Browning Automatic Rifle) is a beast of a firearm. Weighing 16 to 20 pounds, the gun is selective-fire, capable of firing .30-06 Springfield-caliber ammunition in semiautomatic, full-automatic or burst modes. The rifle is fed by detachable box magazines of either 20 or 40 rounds

This so-called “light” machine gun was designed by Browning to be carried and fired by advancing troops while supported with a sling over the shoulder and fired from the hip without stopping or aiming, a concept known as “walking fire.” For more focused, aimed shooting, BAR rifles came equipped with a bipod after 1938.

Military personnel were not the only ones impressed with the firepower and portability of the BAR. Criminals also took notice, two of the more infamous being Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker (“Bonnie & Clyde”), who robbed banks throughout the South and Midwest during the 1930s. Clyde’s weapon of choice was the BAR, which he obtained—along with armor-piercing ammunition—by periodically breaking into National Guard armories.

But Bonnie could also handle one of these heavy rifles, even though she was not a large woman. A Missouri highway patrolman, forced to take cover behind an oak tree when Bonnie opened up on him with a BAR stated, “That little red-headed woman filled my face with splinters on the other side of that tree with one of those d*mned guns.”

Shotgun: Browning Auto-5

A revolutionary design for its day—and the first successful, mass-produced semiautomatic shotgun—the Auto-5 has a squared-off receiver back, earning it the nickname “Humpback Browning.” John Browning designed it in 1898, receiving a patent for the gun in 1900. Produced continually for the next 100 years by several gunmakers, production finally ceased for this fine firearm in 1998.

The name Auto-5 needs a bit of explanation, however. Auto is short for autoloader, not automatic, possibly causing some confusion because the gun has a semiautomatic action. The numeral 5 stands for the total number of shells the shotgun can hold when fully loaded: one in the firing chamber and four in the magazine.

An interesting sidenote is that the famous 20th Century author, shooter and hunter Ernest Hemingway didn’t think much of semiautomatic shotguns in general—preferring instead Browning’s double-barreled Superposed over/under shotgun—but he liked the Auto-5. “I shot a Browning [Auto-5] for twelve years, and it is the only good automatic shotgun,” he said. Ironically, it’s also the gun that nearly killed him.

Hemingway would often invite the rich and famous from Hollywood to Sun Valley Resort in Idaho for fall weekend bird hunts. It was during one of those hunts that socialite Mary Raye Hawks, wife of film director Howard Hawks, was handling a 16-gauge Browning Auto-5 (known as the Sweet Sixteen) less than safely when it went off, barely missing Hemingway—who was kneeling down just a few feet away tying his bootlace. The shot passed so close to the back of Hemingway’s head that it singed his neck hair.

The real test of any firearm is the test of time, and the three guns mentioned above have all passed that lengthy, detailed examination with flying colors. But Browning had many other successes, as well, such as the development of various Winchester rifles, and the water-cooled M1917 and air-cooled M1919 heavy machine guns. And yet today, when the legendary Browning M2 .50-caliber “Ma Deuce” machine gun arrives on the battlefield, enemies scatter.

John Moses Browning died doing what he loved best, inventing and designing firearms. While at his workbench one day in 1926, at the age of 71, he simply slumped over and slipped into firearms history.

I reckon so!

In an effort to piggyback off another’s good fortune, companies will inevitably rush in with similar-looking but inferior products. There’s a thriving black market for fake designer handbags and jewelry that seem like identical copies of their fancier counterparts — at least until they fall apart at the seams or stain your skin green. Your child’s room may have a mimic hiding in plain sight: perhaps a well-meaning relative bought your son a robot “Transmorpher” instead of an honest-to-God Transformer, or maybe your daughter owns a generic “Ice Princess” masquerading as Princess Elsa from the Frozen movies.

We often make the mistake of thinking knockoff goods are a modern problem. In fact, one of the most well-known firearm brands still carries an interesting reminder of a time when its counterfeits saturated the market. On the side of every modern-era Smith and Wesson revolver, you’ll find what collectors call the “four line” rollmark. The first line reads: “Made in U.S.A.” The final two read: “Smith & Wesson” followed by “Springfield, Mass.” But somewhat oddly, the second line is Marcas Registradas. It’s a Spanish phrase translating to “Registered Marks.”

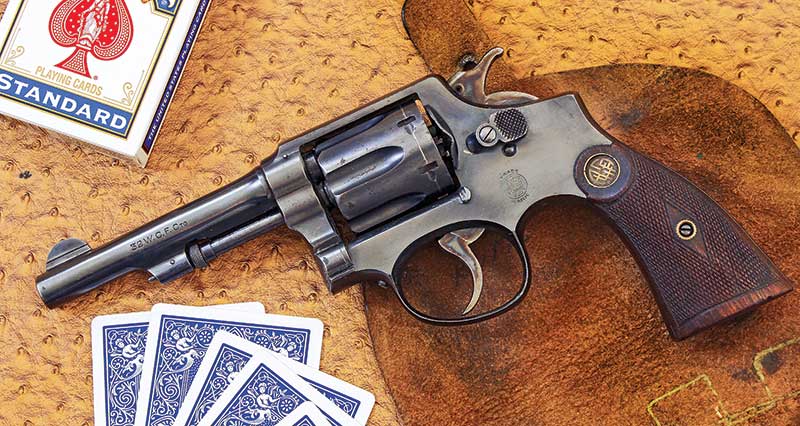

To understand how the line came to be, I call your attention to the “Spanish clones” of the old .38 Hand Ejectors — the parents of the venerable “Model 10” revolver S&W still sells today. My clone, technically known as an Armero Especialistas, “Alfa” model, proves to be an especially fascinating chameleon.

History Lesson

Around the turn of the 20th century, Smith and Wesson’s flagship K-Frame became big news and big business for the Springfield firm. Innumerable Spanish competitors decided they wanted in on the action and began producing a bewildering variety of blatant copies in an effort to meet demand for the awesome guns — and undercut the existing market.

Naturally, S&W found out about this skullduggery and attempted to put a stop to things. While they had some legal success going after American importers on the grounds they were intentionally attempting to defraud consumers, the sovereign nation of Spain essentially told them to pound sand — they didn’t recognize their American trademarks. S&W did eventually secure patents abroad but only after the knock-offs existed on the international market for several decades. S&W added the Marcas Registradas as a way of saying “Stop copying this design!” in a language its counterfeiters would definitely understand but by then, the damage was done.

So what to make of these guns as a whole? First, let’s start with the reality many of the Spanish copies were downright janky. On the low end, there are several design elements that stick out even to the casual observer as being not right at all. It’s common to find design details appearing to be sketched out from memory. Cylinder releases can be of strange teardrop or circular contours, dimensions can look squashed or stretched and often hammers tend to have unusual shapes.

Hilariously, some rollmarks claim the guns are made in “Sprangfeld, Mus.” Others attempt to vaguely match the iconic S&W “Trade Mark” logo with a blobby, sloppily rollmarked forgery. Often, the substandard finishes have worn completely away in the last hundred years and metallurgy is so questionable firing the guns is generally regarded as a bad idea. There are many, many unconvincing fakes.

Some Aren’t Bad

This “Alfa,” however, is a pretty damn successful copy. Every signature contour of the Smith-pattern revolver is mostly intact here down to the smallest of details. The front sight blade, ejector rod, hammer, cylinder release, grip shape, frame dimensions, screw orientation, sight groove and frame detailing are all basically dead ringers for the real thing — it’s almost insidious, really. The barrel appears to be pinned and the quality of walnut stocks are top notch. Even the machining on places like the cylinder ratchet, hand and lockwork is pretty good, and the bluing looks great for being about a century old!

With all this in mind, it helps to remember Spain has a rich history of firearms production stretching back centuries. Consequently, a lot of gunmakers weren’t exactly banging rocks together when they made these guns. There’s clear craftsmanship here — even some “improvements.” For example, many of the Spanish copies used a single beefy V-Spring — not unlike a Colt — in place of three separate springs on the original S&W design. On paper, this made the design slightly less fragile, and in theory, better-suited to military service. The French government went so far as to order many “Spanish Model 92s,” as they were then known, as fighting handguns during World War I.

This robustness, however, has a clear cost. While just about any S&W revolver has a pedigree of being something you can pick up and shoot quite easily, the trigger on this copy flat-out sucks. The double-action mode is easily on par with the worst revolvers I’ve ever shot: the V-Spring stacks for days at the end of an already-stiff travel. But even more impressive in its awfulness is the single-action trigger, which is just as heavy. Mechanically, one spring is both keeping the hammer under tension and pushing the trigger forward, whereas on legitimate S&Ws these are two separate jobs parted out to separate springs.

The effect is a single-action trigger pull in the vicinity of 11 lbs. Yes, 11 lbs. It’s definitely over the 10-lb. limit of two separate trigger gauges I have laying around so the additional pound represents a conservative estimate. I’ll note I can’t attest to mechanical accuracy of the gun: Given my nagging concerns of the metallurgy of any Spanish clone, even one as seemingly well-built as the Alfa, I’ll likely never shoot it. However, given the horrendous trigger, I doubt I’d be fruitful in obtaining any trustworthy data related to how it groups. Also — I have actual Smith and Wessons more deserving of range time.

Pop Quiz

Let me end by asking you this: Had I not told you this was a Spanish clone, would you have been fooled? Admittedly, I overpaid to get the best fake I could.

Some eagle-eyed S&W fanatics would have examined the grip logos and the slight, slight difference in the shape of the trigger guard and immediately suspected something was amiss from your standard five-screw M&P. Would-be sleuths also have the internet now, so it’s easier than ever to pull up side-by-side photo references of a legit gun to compare with the copy.

But say you’re a vaquero in the 1920s who goes into a local gun store looking for one of “those new Smith & Wesson revolvers,” and the guy behind the counter says, “Sure, we have those! And at a cheaper price than you were expecting!” Or, maybe you’re an American shooter who wants one of these nifty double-action revolvers with a swing-out cylinder in .38 special. You know, just like the one you shot at your brother-in-law’s last summer — doesn’t the gun behind the counter look just like what you remember? Long story short, I imagine the tricksters at Armero Especialistas were extremely successful at cutting into Smith & Wesson’s business.

Today, the Spanish copies are little more than a historical curiosity. While I would certainly have no qualms taking a well-worn example of an actual S&W .38 Hand Ejector to the range or conscripting it for self-defense if it were all I had, the Spanish clones are a poor choice for sport or social work. That being said, I think every serious S&W collector should have one or two clones in their collection. They are fantastic conversation pieces, not particularly expensive and hearken back to a profoundly interesting time in the company’s history.