Suppose they gave a war and nobody came? The United States is gearing up for a possible war with China, but it faces a serious recruitment problem. The nation’s youth can’t meet basic standards.

Earlier this year, the Council for a Strong America reported that 77 percent of 17- to 24-year-olds are ineligible for service. About 44 percent of young Americans can’t serve for multiple reasons. More than 20 percent are simply too fat.

The Council didn’t have any good ideas. It discussed the benefits of the SNAP food program and suggested that policymakers “promote healthy eating, increased access to fresh and nutritious foods, and physical activity for children.” A country whose citizens are too stupid to feed themselves without the government both paying for it and telling them what to eat has problems.

“The poor are the first to fight” is a lazy slogan that suggests social hierarchies are illegitimate because the elite won’t fight the wars it starts. Historically, that isn’t true. The very poor and the lumpenproletariat don’t make good soldiers.

The aristocracy bore the burden of combat well into the 20th century. Vanity Fair reported in March 1916 that more than 800 titled men died in the first 16 months of World War I, a butcher’s bill higher than that in “the Great Rebellion against Charles I.” “[A] whole generation of the nobility will have been wiped out by the time peace is declared.” Even the Irish Times marveled at the willingness of the highest levels of the aristocracy to die for King and Country. Twenty-four peers died in the war, and the British aristocracy arguably never recovered. Officers died at a higher rate than enlisted men.

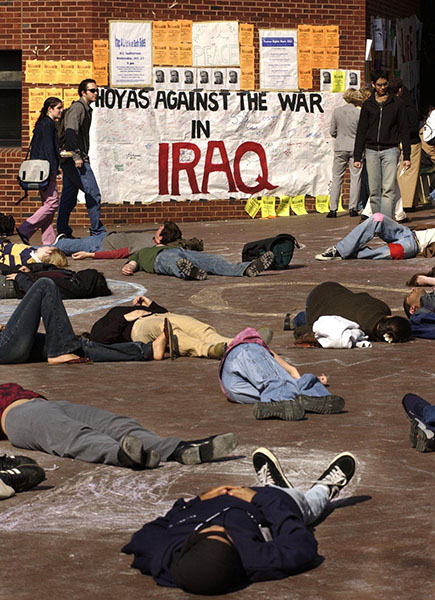

The United States lacks a responsible aristocracy. In 2006, just a few years after 9/11, fewer than 1 percent of Ivy League graduates joined the military and about 1 percent of Congressmen had a child in uniform. ABC reported that many upper-class Americans didn’t want to support an “immoral” war in Iraq or Afghanistan. In 2015, just 20 percent of elected officials had military experience and a 2021 Pew poll found the proportion of veterans in American society was declining.

Today, the American military relies heavily on the middle class, especially from the South. Sixty-four percent of recruits come from neighborhoods where households make between $41,692 and $87,850. Just 17 percent come from neighborhoods that are better off than that. A roughly equivalent share come from poorer neighborhoods. The South is overrepresented, producing more than 40 percent of all recruits. New England and the West Coast are underrepresented. South Carolina is the most overrepresented; DC (if we count it) is the least.

Behind all these other problems lurks race. The Army is 54 percent non-Hispanic white and almost 70 percent of officers are white. According to the 2021 Demographics Report, 68.9 percent of all active-duty military are white, including 67.5 percent of the enlisted. However, these figures do not break out Hispanics, many of whom are counted as white. In the Selected Reserve, 73.1 percent are “white.” About 17 percent of all active-duty military are black, including 19 percent in the ranks.

The more non-whites, the happier our leaders are. In a press release about the dismal Council for a Strong America report, undersecretary of defense for personnel and readiness, Gilbert Cisneros, Jr., was upbeat. The report showed a commitment “to ensuring our ranks are inclusive and reflect the country we serve.” Deputy assistant secretary of defense for military community and family policy, Patricia Montes Barron, added, “The information in the report ultimately highlights our diversity and supports the well-being of the military community.”

The military may go further down market. The Congressional Budget Office is considering ways to cut healthcare costs. One option was to “means-test VA’s Disability Compensation for Veterans With Higher Income,” which would save an estimated $253 billion over 10 years. On an annual basis, this would save less than the amount the United States has already spent on the war in Ukraine: about $32 billion. A cut in disability payments would also remove an incentive for the middle class to serve.

Tradition is probably more important. The military no longer celebrates the white Southern military spirit, despite the continued overrepresentation of Southerners. During the 2020 racial revolution, Democrats and cowardly Republicans defied President Donald Trump and required that all bases named for Confederates get new names. “We’re the party of Lincoln, the party of emancipation, we’re not the party of Jim Crow,” said Rep. Don Bacon (R-NE). “We should be on the right side of this issue.” Nine names would go, including Robert E. Lee, A.P. Hill, and George Pickett.

The Defense Department is very clear that this was a repudiation of the South — and Donald Trump — and part of George Floyd hysteria:

Some Army bases, established in the build-up and during World War I, were named for Confederate officers in an attempt to court support from local populations in the South. That the men for whom the bases were named had taken up arms against the government they had sworn to defend was seen by some as a sign of reconciliation between the North and South. It was also the height of the Jim Crow Laws in the South, so there was no consideration for the feelings of African Americans who had to serve at bases named after men who fought to defend slavery.

All this changed in the aftermath of the police killing of George Floyd in 2020. Many people protested systemic racism and pointed to Confederate statues and bases as part of that system. Congress established the commission in the National Defense Authorization Act of fiscal 2021. Then-President Donald J. Trump vetoed the legislation because of the presence of the commission, and huge bipartisan majorities in both houses of Congress overrode his veto.

Black Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin praised the Naming Commission’s efforts to “remove from U.S. military facilities all names, symbols, displays, monuments, and paraphernalia that honor or commemorate the Confederacy,” instead choosing names that “echo with honor, patriotism, and history” and will “inspire generations of Service members to defend our democracy and our constitution.” Those turn out to be names of insignificant non-whites.

One exception is Fort Bragg, named for General Braxton Bragg, which will become Fort Liberty. The name change will cost more than six million dollars. Officials say this bland name “conveys the aspiration of all who serve.” Fort Bragg is also renaming all the streets named after Confederates. No doubt this will cure the base’s problems: 31 fatal drug overdoses from 2017 to 2021, 41 suicides in 2020 and 2021, and 11 soldiers murdered or charged with murder from mid-2020 to September 2022.

Since President Trump left office, the military has been trying to purge “extremists.” On February 5, 2021, Secretary Austin signed a “stand-down” order for all officers to grill their personnel about “extremist or dissident ideologies.” The New York Times cheered efforts to “root out far-right extremism in the ranks,” though it accused the military of “downplaying white nationalism and right-wing activism” in the past. The SPLC wants more prohibitions on social media posts as well as “screening, education, and training to prevent recruitment of extremists into the military, to inoculate against radicalization for active-duty personnel throughout their military careers.” This will mean careers for activists who have an interest in expanding the definition of “extremism” indefinitely.

The military realizes there is no good definition of “extremism.” In a May 2022 report, DoD recommended a more explicit definition as well as more data from the Office for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. However, even before the brass figure out what is extreme and what isn’t, it has started its own extremist indoctrination.

In June 2021, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Mark Milley justified teaching critical race theory at West Point: “I want to understand white rage,” he said. “And I’m white.” He said he wanted to know what “caused thousands of people to assault [the Capitol] and try to overturn the Constitution of the United States of America.” General Milley obviously would rather demonize whites than understand them. About two months later, he presided over the fall of Kabul. He didn’t have the integrity to resign.

In June 2020, Air Force Chief of Staff Dave Goldfein said he was outraged over the death of George Floyd and was moved to denounce “racial prejudice, systemic discrimination and unconscious bias.” “As leaders and as airmen we will own our part and confront it head on,” he said. A colonel, Ben Jonsson, wrote an article called “Dear White Colonel” that concluded by telling people to read White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo. That book explains that all whites are racist no matter what they do. Fighting racism is a military priority now, so whites are on the defensive throughout their careers.

Internal training materials warn of many threats, including “Patriot Extremism.” “This ideology holds that the US government has become corrupt, has overstepped its constitutional boundaries or is no longer capable of protecting the people against foreign threats,” it said. All races may become infected with “Ethnic/Racial Supremacy,” but “the vast majority of these groups hold white supremacist views.” Among the symbols listed as “extremist” are the Oath Keepers logo, Pepe the frog, the Three Percenter logo, the Proud Boys logo, and, remarkably, the slogan “Come and Take It” with a rifle. Identity Europa was an extremist group.

White identity politics is pathological, but blacks, women, Hispanics, Asians, homosexuals, and even transgenders get praise. In 1999, the Triangle Institute for Security Studies found that those in the military were far more likely to call themselves Republicans, want a ban on homosexuals in the military, and support school prayer. One professor at the National War College called this “scary.” He can be happy now; those views could get you a discharge.

Yesterday, before Congress, military leaders passionately defended wokeness. “Diversity, equity, and inclusion are essential to unit cohesion and trust,” claimed undersecretary of defense for personnel and readiness Gil Cisneros. Officials from the Army, Navy, and Air Force made similar claims. When Republicans criticized DEI, Rep. Steven Horsford (D-NV) explained idiotically that it was needed because veterans were in the January 6, 2021 riot.

There were questions about Kelisa Wing, the former head of the Department of Defense’s school system. She had tweeted: “I’m so exhausted at these white folx in these [professional development] sessions this lady actually had the CAUdacity [Caucasian audacity] to say black people can be racist too.” Miss Wing wasn’t fired; she was moved to a new job just three hours before the hearing began. Unlike “extremists” ejected from the ranks, she’ll keep getting a paycheck. “I have a feeling that has to do with the fact that we [Republicans] have shined light on this,” said Rep. Elise Stefanik. There are surely far more like her who either are wiser about social media or have deleted their tweets. In any case, what she said is no different from what White Fragility teaches.

The Army had a recruitment target of 60,000 last year but it missed it by 15,000. The Army wants more than 500,000 active-duty soldiers, but may have fewer than 450,000 next year. The Air Force is expected to miss its target; the Navy missed its target for officers. Only the Marine Corps made its quota.

I suspect “wokeness” hurts recruitment, but the collapse into drugs, crime, and obesity may have more to do with it. Senator Jack Reed (D-RI) denied that an obsession with diversity hurts recruitment. “Diversity and inclusion strengthens our military,” he said. “By every measure, America’s military is more lethal and ready than it has ever been. It is also more diverse and inclusive than ever before. This is not a coincidence.” What’s his evidence for this?

The Army’s head of marketing said the real problem is that the service isn’t “relevant” to most Americans. I wonder why not.

In The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations, Samuel Huntington explored the relationship between the military and the society it defends. While the two can’t be too distinct without risking disaster, they can’t be equivalent. “Military institutions which reflect only social values may be incapable of performing effectively their military function,” he wrote. The armed services, one of the few institutions that most Americans still think is functional and competent, are always a tempting target for politicians who want to “prove” that racial integration and leftist values work. The risk is that soldiers become social workers with rifles.

Some would say that’s what we already have.

Naturally, because the military follows civilian authority, officers can’t tell Congress that blacks don’t perform at the same level, that co-ed units fall apart, or that you can’t have both diversity and competence. Besides, unlike in regular society, officers can still enforce at least some minimum standards and use force to impose discipline. Everyone in uniform is smart enough to pass the ASVAB, an IQ test of the sort banned by the Supreme Court in Griggs v. Duke Power Company because of “disparate impact.”

However, before the military can use force to make different groups get along, people need to sign up. Here, the brass face a more fundamental problem. The Army’s motto is “This We’ll Defend.” What’s “this”?

The government is officially suspicious of white men even though, historically, they are the military. Their sacrifices made the United States a superpower. However, victories over Mexicans and Indians don’t fit well into the story of white oppression. Nor is Christianity welcome in a military that celebrates homosexuality and transgenderism. Nor are there many white American heroes the military can claim without offending someone. Yet if those heroes and that history are bad, why should white men join up?

Non-whites have a different problem. If America is defined by racism and white supremacy, why should they be willing to die for it? Instead of the military telling non-white Americans to be loyal and brave, a diet of Critical Race Theory tells them that the armed forces — like all other American institutions — is poisoned by racism. Furthermore, DEI programs give non-whites a reason to look for grievances, both to get ahead and eliminate white rivals.

The hunt for “far-right extremism” is a fool’s errand. Soldiers have to be “extremists.” Killing foreigners because they are a threat to the nation is practically a definition of “right-wing extremism.” The willingness to die also requires a sacrifice that mystically values the nation or an ideal of honor above rational self-interest. Even in self-loathing Germany, perhaps the most ideologically policed nation in the West, “right-wing extremism” is a problem in the military. It always will be.

If anyone can be an American, and the services militantly defend diversity, why should anyone be ready to kill or die? You might learn a trade in the army, but why sacrifice for it? There are white men who are old-fashioned enough to love America because it’s theirs, but they are old-fashioned, dangerous, and unwanted. If they join anyway, they may face a dishonorable discharge if they are too vocal about patriotism or say things any other generation of soldiers would have taken for granted.

However, conservatives who worry that this “weakens” America are missing the point. Bolstered by technology, enjoying a vast network of alliances, and controlling great media power, the American military is hardly weak. The Russian army may have had tough-as-nails recruitment ads, but that is not enough against superior technology and international financial hegemony. The war in Ukraine remains unsettled, but my point is that America may remain the hegemon at the expense of white America itself.

The American military is anti-white. That’s why the chairman of the joint chiefs lectures Congress on white rage and reads Robin DiAngelo. There will always be “far-right extremists” in the ranks, but they won’t hold power. Instead, it’s more likely they will be cannon fodder.

Sam Francis argued in Leviathan that while most elites in history had an interest in conservative values that preserved hierarchy and the continuity of society, the modern elite does not. Instead, it relies on manipulation and soft power to stay in power. Rather than relying on the solidarity and strength of a united nation, the American ruling class retains its position by cultivating grievance groups to use against enemies. These groups also are the institutional basis and ideological justification for retaining power.

America does the same thing overseas. The State Department, NGOs, and activists use “color revolutions” to destroy opponents. We saw the same thing domestically in 2020, as the country’s dominant institutions turned decisively against the nation’s own past.

The real question for us is not to worry about whether America is “tough” enough to fight China, Russia, or Iran. It’s whether we can look at the current order and say “this we’ll defend.” If the answer is no, white Americans shouldn’t fight, unless they want to wear the uniform for their own purposes. Even if they do, they should have no illusions about what they are fighting for, nor any pretense they are part of the same institution American soldiers once served.

I’m not encouraging sedition. You can obey the law, pay your taxes, and be a good citizen without volunteering to die for people who despise you. White Americans have to ask whom this regime represents.

The brass may also be wondering. The Army recently made an ad that — although it has a black narrator — showed white men in a positive light and appealed to the past. If the comments on YouTube are any indication, the target audience saw though this farce. See for yourself before they delete the comments.

These comments — “I’m never dying for people who hate me,” “They can fight their own wars,” “The men who fought WW2 would have joined the Nazis if they could have seen what their country would become” — show something real. Recruitment shortages will continue even as the regime picks more fights internationally. Even with money, media power, and technology, a real war takes men on the ground with guns. Our rulers are probably crafty enough to avoid a direct conflict, but if they slip up, they will have a terrible time convincing white men to fight and die for a regime that is replacing them. It may have an even harder time telling non-whites to fight for a “racist” country.