The New York Post is reporting that nearly two dozen struggling homeless veterans have been booted from upstate hotels to make room for migrants, at least according to a nonprofit group that works with the vets.

P53 Enfield Turkey Shoot

“AT HOME WITH GUNS”

CALIFORNIA DREAMING By Aristophanes

“Best way to live in California is to be from somewhere else.”

— Cormac McCarthy, No Country for Old Men

The beacon of hope that used to be California is now a fading memory. Once the state symbolized the American Dream and prosperity, with classic cars cruising along Muscle Beach and Hollywood glamour drawing talent and beauty from everywhere: today it is a shadow of its former self, drowning in struggle and decline. As a native Californian, it breaks my heart to see my home state in such disrepair. In Texas I feel like a refugee from a country destroyed by some unimaginable disaster. The pain that I feel when I think about California’s current condition runs deep.

I grew up in the 90s in a small farming town in California’s central valley, with an economy built on peach orchards and a state university. Like many rural inland areas, our town was heavily white and conservative and struggled to cope with high taxes designed to support a large welfare class within the big cities. Those taxes enabled service industry workers to survive on low wages that couldn’t keep up with the high cost of living, but also fostered dependency.

In recent years, more people have been leaving California than arriving, a new trend for the Golden State, California has even lost a seat in the House of Representatives due to population decline, while Texas gained one. For my part, one reason I left the state almost a decade ago was because of the sense Californians were resigned to their fate. There was no fight left in the California Republican Party. Conservatives lacked either the influence or the will to wrest back control from the parasitic political consultant class who had captured the party and ran such unappealing candidates as Carly Fiorina and Meg Whitman. The party that had launched the political careers of popular candidates like Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and Pete Wilson suddenly ran out of charismatic candidates. Attempts at governing through popular democracy were also stymied, with Prop 187 and Prop 8 both passing by strong margins only to be struck down later by federal judges. The last GOP majority in the state assembly was in 1994. I was just a kid back then, with no idea the golden age had come and gone.

Despite California’s decline, glimpses of its former glory can still be found. Streets, schools, and buildings in the Bay Area and Sacramento bear the names of war heroes like Dan Daly, and statues of some of the greatest Americans we’ve ever produced are tucked away in parks and streets of small-town California. Take what was once McClellan Air Force Base in Sacramento, now a business park. The Barracks have transformed into the Lions Gate Hotel, with the former Officer’s club serving as a bar, its walls adorned with pictures of the base’s history. The Squadron buildings are now cheap, asbestos-filled office space, occupied by homelessness NGOs that seem unable to do more than help the mentally ill and addicted subsist until they perish.

But just a few miles away, slumbering California can still be found. Away from the main urban arteries, American flags hang from homes, and carefully preserved classic cars are a common sight.

When I go back to California to visit the family I still have there, I’m moved by the memories of the best parts of my childhood. I’m lucky enough to remember the idyllic “old California.” Violent crimes were so rare that they were the talk of the town when they did happen. I remember 4th of July block parties, where we could still legally use our own fireworks. We would watch the massive fireworks show put on by the university and then produce one of our own. The whole street would assemble in front of a neighbor’s house, and everyone would take turns lighting off fountains and mortars for hours. Halloween enjoyed almost universal participation, and no one was afraid that it would be unsafe for kids to take to the streets in search of candy on their own. I walked to my elementary school, starting in first grade, with no fear of getting snatched up.

But in 2001, the old world came to an end for me, a little sooner than it did for most. My parents had been fighting and considering a trial separation for a few years, and my dad had fallen into a deep depression. He was prescribed the antidepressant Paxil, but 9/11 was the final nail in the coffin for him. The spark of optimism he still had preserved flickered out, and a month later he took his own life. Paxil would later face class action lawsuits over its role in driving depressed men like my dad to rock bottom. The California Dream ended for me that day, and ignited the rage I feel.

***

“They paved paradise and put up a parking lot.”

— Joni Mitchell, Big Yellow Taxi

No stretch of California evokes memories more vividly for me than the stretch of Highway 65 and Highway 70 from the northern edge of Sacramento to the mountain town of Paradise. In the summer the vast fields of haygrass resemble yarn spun from gold. Elkins Frosty, with its proud banner proclaiming the best (and only) burgers and shakes in town since 1976 recalls simpler times. Then, after the Oroville Dam, you reach the ill-fated town of Paradise.

Like many logging towns in the Northern California mountains, Paradise was devastated by the Sierra Club’s campaign to destroy the State’s logging industry in the name of conservation. With its primary industry gone, these towns sunk into economic decline. Most of the young people moved out, while drug use and petty crime increased. Eventually the economy consisted largely of retirees and the government, a situation now common to small towns across America following deindustrialization. Then, in 2018, the devastating “Camp Fire” wildfire burned Paradise to the ground, leaving only ashes and devastation in its wake.

My aunt and cousin, who had spent most of their lives in Paradise, lost their homes. Scores upon scores of homes were reduced to nothing more than concrete pads. But my great-grandmother survived. Her home was spared, and she returned as soon as she was allowed before recently passing away at the age of 92. It was her funeral that brought me back to Paradise and gave me a chance to see how the town was doing with its rebuilding efforts.

Despite the scars left by the Camp Fire, still visible on the trees that survived, Paradise has a feeling of new life to it. Slogans of solidarity and pride are scattered throughout the town: “Paradise: Rebuilding The Ridge,” “Paradise Strong,” and “Faith & Hope In Paradise.” Many of the buildings that were destroyed have been replaced with structures made of steel. There are new businesses everywhere, funded by fire insurance money and new investments. A charred metal Burger King sign without a building to go with it is all that remains of the many big corporate franchises that have yet to return. With the overgrowth swept away by the fire, enriching the soil, Paradise is an example of the cycle of destruction and rebirth that nature destines for all its creations.

***

“And home isn’t here and home isn’t there.”

— Deborah Landau, The Last Usable Hour

It is difficult to suppress the notion that the apathy towards the issues plaguing rural communities in California may be attributed to the disconnect between the political and financial power centers of the state and these areas. Over the past decade, the population of California saw a ten percent increase, with the majority of growth concentrated in urban areas. This influx has resulted in a class of urban parasites who have displaced native residents due to the growth of housing demand and have also imposed their own values and priorities upon these areas. The stereotype of the progressive middle-class “Californian” nobody wants to move into their red state was more than likely born in Pennsylvania or Ohio.

This new class has overrun the state, treating the residents as collateral damage in their search for upward mobility and acceptance within their adopted lifestyles. They have abandoned their roots, and in doing so, have turned a blind eye to the struggles of the folk that resembles their heartland kin. These problems, which closely mirror the struggles of their own families and hometowns, are now distant and insignificant to the political power that stems from the cities. As a result, there are no repercussions for neglecting to address them.

California today is at a crossroads. Will it be able to reclaim its former glory, or will it continue to decline? Time will tell. The once great state is now ravaged by poverty and corruption. The glamour of Hollywood and the prosperity of the gold rush and railroad seem like distant memories, preserved only in film. The pension obligations of its bureaucracy are in danger of going unfunded, while unions wield their power to prevent necessary changes. The Golden State is setting itself up for a catastrophic reckoning, but perhaps that is the only way it can be revived. Like an overgrown forest, California needs a firestorm to raze it, so that seeds of the future can be sown once again.

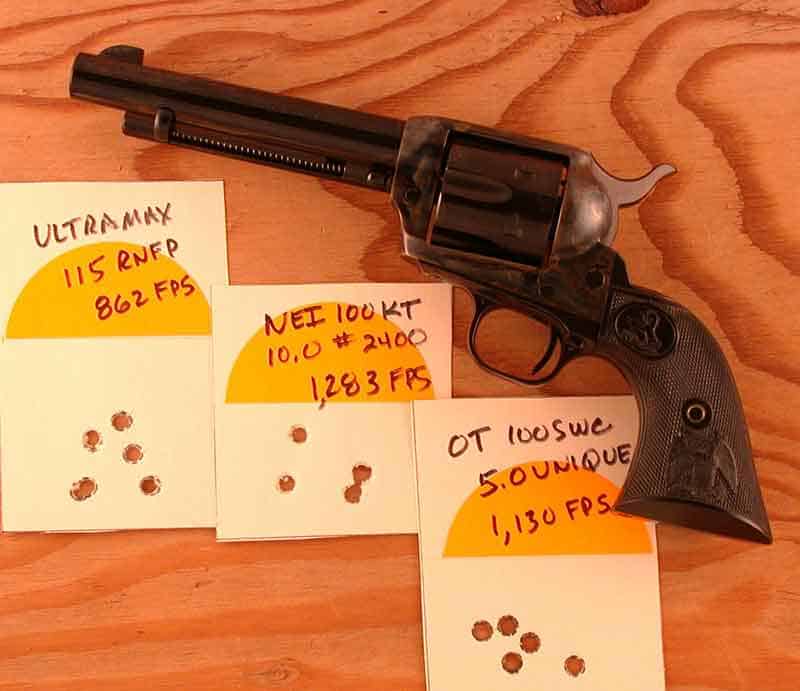

William Mason, chief engineer at Colt, came up with one of the grandest sixguns of all time, the 1873 Single Action Army. I’ve often maintained the SAA is so good Mason must’ve fallen asleep at the drawing board and some supernatural force drew up the plans in front of him as he slept.

Colt’s new sixgun was chambered in a new cartridge—the .45 Colt with a 255-grain bullet over 40 grains of black powder. Barrel length was 7-1/2″, it had a top strap and the grip frame was borrowed from the 1851 Navy. This was a very powerful pistol, and when I have duplicated the load with modern components in old-style brass, muzzle velocity is right at 900 fps.

The US Army did not only adopt this new revolver, but it also became a favorite among civilians. Colt would produce more than 350,000 Single Action Army revolvers from 1873 to 1940. Beginning in 1878 it was also chambered in the cartridges used by the Winchester 1873 levergun—first, the .44 Winchester Centerfire, then the .38 WCF, and the .32 WCF. During the course of production of what is now known as the 1st Generation Colts, these four cartridges were the most popular and in the order mentioned. More than 30 other chamberings were also offered.

By 1940 demand for the Colt Peacemaker had dropped and the machinery was worn out, so Colt removed it from production. Thanks to the demand produced by old Westerns on the new medium of television in the early 1950s such a demand rose the first of the 2nd Generation Colts arrived in December 1955. This time production would last a much shorter period ending in 1974 when machinery was once again worn out.

This time the shutdown period was much shorter and the 3rd Generation Colts arrived in 1976. Since then, the Colt Single Action Army has followed a somewhat strange path sometimes offered as a production gun and other times from the custom shop. The bad news is quality has also been spotty, however, the great news is current Colt Single Action Army sixguns are of excellent quality with close attention paid to fit and finish. Colt has added new machinery and adopted the attitude of wanting to produce the finest Single Action possible. I’d say they’ve succeeded.

I received three test sample SAAs in the three standard barrel lengths of 4-3/4″, 5-1/2″, and 7-1/2″ in three different chamberings. Colt is currently offering the Single Action Army in .45 Colt, .357 Magnum, .38 Special and the three WCF chamberings. The latter three are now better known as .44-40, .38-40 and .32-20. It is my understanding these latter designations came about in the 1880s when Marlin wanted to chamber their rifles in these cartridges without using the name Winchester on their barrels.

Before we look at each of the three SAAs separately, a few general remarks are appropriate. All three are excellently finished with a beautiful deep blue and the breathtaking case hardened colors Colt has long been known for. Metal to metal fit is excellent with no overhanging edges such as where the triggerguard meets the bottom of the mainframe. The grips are the standard checkered rubber black eagles, and are also fitted exceptionally well with no sharp edges hanging over, and the ears of the top of the backstrap and the curve of the back of the hammer are also fitted very well.

I was especially impressed with the lockup of the cylinder. The bolt is fitted to the notches in the cylinder, the cylinder is fitted to the base pin, and the base pin is fitted to the frame so there is very little side-to-side or front to back movement of the cylinder. All three sixguns are very well timed. An old test to check for timing is to place light thumb pressure on the cylinder producing resistance as the hammer is cocked. If the timing is off the cylinder will not lock completely into battery. All three cylinders passed the test. These guns are put together right!

The .44-40

Let’s look at them individually starting with the shortest barrel length. The 4-3/4″, known as the Civilian Model in the 1800s, is in .44-40. Trigger pull on this one was set at 4-1/8 pounds, barrel/cylinder gap is .006″, and the cylinder throats are all a uniform .429″. There is a lot of variation found in Single Actions, both domestic and replicas chambered in .44-40. I have found some as tight as .426″ and my 2nd Generation Peacemaker Centennial Commemorative and early 3rd Generation are set at .427″ and .429″, respectively. As a bullet caster, I tailor bullets to fit particular sixguns and always keep loads on hand with bullets in both diameters.

Shooters, especially those not familiar with the traditional fixed sights found on Single Actions often ask, “Why can’t they sight in these guns for me at the factory?” They are asking the impossible, as there are so many variables. We all see and hold differently, point of impact will vary according to the load used, and even the lighting conditions will affect where the bullet strikes the target. Because of the latter, I never try to sight in a sixgun under indoor lighting. I have also noticed if you spend a lot of time shooting during the day, the point of impact will change slightly as the angle of the sun changes. If you’re really lucky a Single Action will shoot right to point of aim with the selected load right out of the box. Anyone this lucky should be buying lottery tickets.

Having said all this, the .44-40, in my hands using my eyes and my loads, shoots approximately 1″ to the right and 3/4″ low at 20 yards. Both of these are an easy fix thanks to my friend Denis Fletcher, a retired engineer, who is now a pretty good machinist. He made a barrel vise for me, which fits the trailer hitch on my Silverado. We have become experts at twisting barrels and it won’t take much to bring this one right into line and, once the load is selected, file just enough off the top of the front sight to bring point of aim in perfect alignment with point of impact.

I have pretty much standardized on 200- to 225-grain bullets for the .44-40 using 8.0 grains of either Unique or Universal or 8.5 grains of Power Pistol. In the relatively short-barreled .44-40 these loads are in the 850 to 900 fps category, making them adequately powerful while still very pleasant shooting.

The .32-20

Next up is the 5-1/2″ .32-20. Trigger pull on this one is 4-3/4 pounds, barrel/cylinder gap is .005″, while the chamber throats are a uniform .313″. This one is dead on for windage and shoots about 1-1/2″ low so a few file strokes will bring it right to point of aim.

Two standard loadings for the .32-20 for decades has been 5.0 grains of Unique or 10.0 grains 2400. These loads put the .32-20 into the Magnum class and should not be approached lightly. (They are only for large-framed revolvers and never should be used in either the S&W M&P or the Colt Police Positive.) Both of these loads shot well with 100-grain cast bullets. Recoil in the relatively heavy Colt is extremely mild. This .32-20 would make an excellent varmint pistol, and no can or rock at a reasonable distance would stand a chance.

The .38-40

Finally we come to the 7-1/2″ .38-40. My first Colt, my first centerfire sixgun, was a .38-40 and it has been a favorite cartridge ever since. (OK, so I have many favorite cartridges.) This SAA has a trigger pull of 4-1/2 pounds, barrel/cylinder gap of .007″, and cylinder chamber throats are a uniform .399″. This one will definitely need a barrel tweaking as it shoots 2″ to the right for me and 3/4″ low.

In a properly set up sixgun, the .38-40 is a very accurate cartridge. It got a bad rap in the early days simply because chamber throats and barrel diameters did not always match up very well. This is no longer the case. My standard load for the .38-40 is 8.0 grains of Universal or Unique under a 180-grain cast bullet. Muzzle velocities are in the 1,000 to 1,100 fps, again, resulting in a powerful but pleasant shooting load. All test results are in the accompanying chart and reveal what an excellent performer this Colt Single Action really is.

All three of these are test guns on loan, however, all three of them are not going back. I will definitely purchase one of them (there is no way the .38-40 will ever leave my hands), possibly two, and if finances are in line, all three. I can’t give them any finer recommendation than that.

Single Action Army

Maker: Colt Mfg. Co.

545 New Park Ave.

West Hartford, CT 06110

(860) 236-6311, www.coltsmfg.com

Action Type: Single Action

Caliber: .32-20, .38-40, .44-40 (tested) .45 Colt, .357 Magnum, .38 Special

Capacity: 6*

Barrel Length: 4-3/4″, 5-1/2″, 7-1/2″

Overall Length: 10-1/4″, 11″, 13″

Weight: 39 ounces (varies)

Finish: Blue/Case Hardened Frame, full nickel

Sights: Fixed

Grips: Checkered black eagle

Price: $1,290, $1,490 (nickel)

*For safety, this revolver must be carried with the hammer down on an empty chamber, reducing capacity to five.

Black Hills Ammunition

P.O. Box 3090, Rapid City, SD 57709

(605) 348-5150, www.black-hills.com

Walt Ostin of Custom Gun Leather

39-1260 Fisher Rd. RR 2

Cobble Hill, BC, VOR ILO Canada

(250) 743-9015