America’s enduring Model 1911 .45-cal., semi-automatic pistol remains a landmark sidearm more than a century later. Yet how it was introduced to service and typically carried by soldiers, sailors and marines before World War I remains lesser known.

Self-loading handguns became possible with the French invention of smokeless powder in 1884. Two blue-blooded Austrians, Karl Salvator and George von Dormus, patented their pistol in 1891, which held five rounds of proprietary 8 mm ammunition. It failed to find a market, but an improved version by another Austrian, Josef Laumann, entered production at Steyr the next year.

Thereafter, customer interest grew fairly quickly. In 1894, Hugo Borchardt’s C-93 in 7.65×25 mm attracted buyers with its eight-round detachable magazine, followed by Paul Mauser’s iconic “Broomhandle” in 1896, with ten rounds of 7.63×25 mm carried internally.

For the most part, the decade produced largely dead-end designs from Germany, Austria, Belgium and Spain, until Georg Luger arose. His 9 mm chambered P08 (for 1908) was first accepted by Switzerland in 1900, then by Germany along with many other nations.

In the United States, John M. Browning filed his first pistol patent in 1895, leading to the Belgian firm Fabrique Nationale’s hammerless .32-cal. Model 1899, followed by the enormously popular Model 1900 in .380 ACP. Retaining the detachable magazine but with grip and thumb safeties, the Model 1903 was produced in .32 and .380. Between them the Models 1900 and 1903 probably sold more than 850,000 units.

Placed in context, the .45 ACP emerged at the end of more than a decade of sidearm development. The M1892 was the first U.S. double-action revolver with a swing-out cylinder, chambered in the anemic .38 Long Colt. Adverse reports from the Philippine Insurrection, fought from 1899 to 1902, led to the M1909 in .45 Long Colt. A succession of variants emerged, with the stocks of the M1903 narrowed to provide an improved grip.

The stage for the M1911‘s development and adoption was set in 1907, when an Army board decided to replace its standard-issued revolver. Colt and Browning had collaborated on a nascent .41-cal. pistol round, but the Army’s Thompson-LaGarde ballistics tests of 1904 influenced development. Consequently, Browning modified the new cartridge as with a 200-grain, .45-cal. bullet, launched at 900 f.p.s. The round appeared in the prototype Colt Model 1905, and after extensive testing by military and industry representatives, the final combination yielded the classic .45 ACP cartridge, with its 230-grain projectile launched at upwards of 850 f.p.s.

Army Ordnance concluded, “After mature deliberation, the Board finds that a bullet which will have the shock effect and stopping power at short ranges necessary for a military pistol or revolver should have a calibre not less than .45.”

Several aspirants entered pistols chambered for the new cartridge, and after elimination of other designs (including semi-auto revolvers), Colt’s and the Savage M1907 entries contended for the government contract. In the end, the final selection trial was not even close. The Colt ran flawlessly, while the Savage sustained dozens of stoppages.

As noted by American Rifleman’s predecessor, the April 1911 issue of Arms and the Man, declared, “the good old revolver became obsolete, and in its stead there was marked for the holsters of this Nation’s defenders the .45 Colt’s automatic; the latest, the most deadly, the finest and the best hand arm which had yet to be produced by man.”

Late in the final design process, the Army requested a thumb safety, which Browning added shortly before production began. The service requirement for a grip safety already was met, as Browning’s M1903 set the pattern for the military. Thus, the M1911 .45-cal. pistol evolved in a golden era of small arms design.

The Model of 1911 was adopted that March, with 21,000 delivered through December, including Navy and Marine Corps orders. Aside from the semi-automatic Mauser and Luger pistols, in the same period of time most nations were still introducing bolt-action service rifle designs. Britain adopted the Lee-Enfield rifle in 1895 and Germany’s Mauser designed Gewehr 98 came three years later. America had only adopted the classic Springfield M1903 rifle eight year prior.

Troops quickly noted the weight difference. The M1892 revolver weighed barely 2 lbs., while the Colt M1911 weighed nearly 2.5 lbs. with empty magazine, which may partly account for the decision to mate the pistol and holster to the sturdy 1910 pattern duty belt. The Colt was carried in the M1912 holster, with a twin magazine pouch. Accessories were adaptable to the standard belt, which was frequently updated. Usually it was made of webbing or canvas duck, featuring rows of three vertical grommets to accept hooked hardware for holsters, canteens, and bayonets. Most of these pistols were produced with a lanyard loop in the butt, mainly for cavalry use.

In a 1913 article, Ensign C.E. Van Hook, an influential Navy instructor noted, “Eternal vigilance is the only price of safety.” Yet he commended the semi-automatic, partly because: “The trigger pull always remains the same, which is a decided advantage over the disconcerting double action of the .38-cal., and makes it a great deal more accurate for rapid firing.” As issued, the Colt M1911’s trigger usually lets off at 6 to 7.5 lbs. Van Hook also noted “(the pistol) may be loaded with greater ease and rapidity. This takes into consideration the fact that under service conditions a number of extra clips, loaded and ready for instant use, would be carried in a specially designed belt.”

The M1911’s large frame caused problems for many users accustomed to the revolver’s smaller size. The Naval Institute Proceedings article observed, “One very simple way of overcoming most easily this short finger contingency lies in using the middle finger as the trigger finger. By using the middle finger, even without any previous practice, the shooter can get a better and freer purchase on the trigger.

Moreover, the middle finger is normally stronger than the index finger thus enabling the shooter to execute a smoother trigger squeeze. Let us assume that you are using the middle finger to “pull” the trigger. You will find it convenient to place the index finger either alongside the slide or on the receiver, depending on your own finger length.

However, the Army Ordnance manual of 1912 noted, “The trigger should be pulled with the forefinger. If the trigger is pulled with the second finger, the forefinger extending along the side of the receiver is apt to press against the projecting pin of the slide stop and cause a jam when the slide recoils. Additionally, some military teams allowed carving finger grooves in the 1911’s stocks for improved control, especially in rapid fire.

In 1926, the Army accepted modifications in form of the M1911A1, with an arched mainspring housing, a shorter trigger and frame indents behind the trigger. The annoying problem of hammer bite was largely eliminated with a shorter hammer spur and longer grip safety. However, many shooters preferred the original flat mainspring housing for greater purchase on the grip, and sometimes could retro-fit the original housing.

The Ordnance Departed listed muzzle velocity of 230-grain bullet at 802 f.p.s., penetrating 6″ of pine at 25 yards. Remarkably, trajectory was charted to 250 yards. The maximum ordinate was 4.29 feet (51.5″) at 126 yards. “The trajectory is very flat up to 75 yards, at which range the pistol is accurate.” (As a side note: Joe Foss’ Air Force Reserve M1911A1, manufactured in 1944, grouped with 2″ extreme spread at 20 yards, but 8″ high.)

Reporting on range tests the manual said, “This pistol has been fired 21 times in 12 seconds, beginning with the pistol empty and loaded magazines on a table. Firing at 25 yards at a target 6 feet by 2 feet under the same conditions, 21 shots were fired in 28 seconds, making 21 hits with a mean radius of 5.85″.” (Hatcher’s Notebook, page 421, described mean radius as the average distance of all shots from the center of a group; mean radius usually measured one-third of a group’s diameter.)

When action seemed imminent, the Army’s 1912 Description of the Automatic Pistol suggested topping off to eight rounds. The method seems peculiar today: with the magazine removed, lock the slide open and insert a cartridge in the chamber. Trip the slide release, thus seating the round. Then a full-up seven-round magazine was inserted. It’s unknown how often loose rounds were available in the field. A far more likely technique was chambering the first round off one magazine and reloading with a full mag to bring the total to eight.

Addressing safety features: “The automatic grip safety at all times locks the trigger unless the handle is grimly grasped and the grip safety pressed in. The pistol is in addition provided with a safety lock by which the closed slide and the cocked hammer can be at will positively locked into position.” Decades later, speaking of the grip and thumb safeties, former Marine Lieutenant Colonel Jeff Cooper insisted, “If the 1911 were any safer it would be almost useless as a weapon.”

Decades of gun lore hold that the services originally carried the M1911 “cocked and locked,” or in today’s parlance, condition one. Presumably the policy changed after some negligent discharges. Allegedly, Lt. George Patton fancied himself a gunsmith and “improved” his automatic by filing the sear with exciting consequences, hence his devotion to revolvers. However, documentation indicates otherwise.

Contemporary sources heavily indicate that cocked and locked was only advocated facing imminent threat. The Ordnance manual noted that with a round chambered, “The slide and hammer being thus positively locked, the pistol may be carried safely at full cock, and it is only necessary to press down the safety lock (which is located within easy reach of the thumb) when raising the pistol to the firing position.”

However, Ordnance also advised, “Do not carry the pistol in the holster with the hammer cocked and safety lock on, except in an emergency. If the pistol is so carried in the holster, cocked and safety lock on, the butt of the pistol should be rotated away from the body when withdrawing the pistol from the holster in order to avoid displacing the safety lock.”

The problem, of course, is that it’s impossible to schedule an emergency. It was especially true in combat zones where enemy infiltrators or trench raiders might appear suddenly, at close range, often in darkness. Other concerns involved guard duty at a base entrance or building where emergencies seldom arose but the potential still existed.

The cavalry’s 1940 pistol field manual addressed modes of carry (page 19): “In campaign, when early use of the pistol is not foreseen, it should be carried with a fully loaded magazine in the socket, chamber empty, hammer down. When early use of the pistol is probable, it should be carried loaded and locked in the holster or hand. In campaign, extra magazines should be carried fully loaded.”

More than a century before the bane of today’s gun writers, the U.S. Government initiated the semantic heresy of referring to a pistol as a “revolver” and a magazine as a “clip.” An interwar Navy instruction advised, “Take the revolver in your right hand and the clip in your left. Show him how to insert the clip, trip the slide, inject the first round into the chamber, etc.”

The director of cavalry stipulated that mounted pistol exercises “will be carried on during the entire year.” Furthermore, drill would involve simulated firing at different objects at all gaits from walk to gallop. Most targets were positioned at five to seven yards so troopers were required to engage right and left front; right and left flank; and right rear, the left hand of course holding the reins.

Anyone who has watched a SASS mounted event knows the common cavalry technique: leaning toward a front-aspect target while half rising in the stirrups, thrusting the pistol forward in the most direct line, wrist rigid, and forcing the right elbow to the left in vertical plane with wrist and shoulder. Trigger control was to be coordinated with start of the thrust, “He selects his target, fixes his eyes upon it with concentrated effort, catches sight of the target over his barrel, and squeezes his trigger with steadiness and precision.”

Live-fire drills showed the importance of follow through. Most misses were attributed to troopers’ failure to keep eyes on the target until after the shot was fired. Concentration was paramount. Perhaps understandably in the midst of a cavalry charge, riders tended to look for the next target an instant before the round went. At all times troopers were strongly advised to keep the muzzle well ahead of the horse’s face for obvious reasons.

The manual devoted two pages to training horses not only around gunfire, but getting them accustomed to unusual sizes, shapes, and colors. Long experience showed the wisdom of gradual exposure to unfamiliar objects and conditions, most often in groups rather than individually. Blanks and live fire were introduced as the mounts grew in confidence. Dismounted cavalry courses were fired at 15 to 50 yards, frequently walking toward pop-up targets. Various dates have been cited for the M1911’s combat debut, as early as 1913, but the most likely seems to be Marine Corps use in Haiti from 1915 onward.

In whole or in part, at least thirteen Army men earned the Medal of Honor with M1911s in World War I. Two Marines used Browning products twelve months after the armistice as Lt. Herman H. Hanneken and Cpl. William R. Button wielded both the M1911 and BAR, respectively, in their Medal action against Haitian rebels. Since then, the M1911 has appeared in well over 120 theatrical movies through 2021, plus hundreds of television movies and episodes. That compilation excludes Commanders, Series 70/80s, other manufacturers, blank-firing copies, and portrayals in cartoons and video games.

In the 1969 film The Wild Bunch, a German advisor to the Mexican general notes that the Americans carry handguns “that may not be acquired legally.” In fact, the Colt Commercial “Government” models were marketed in 1912, with an initial run of 1,899 pistols. The civilian market has only expanded in more than a century. Some 110 years later, the M1911 repeatedly finishes atop reader polls as “the most iconic American handgun.” Last year, Shooting Illustrated placed the M1911 ahead of the CZ 75 and Beretta 92, and even the classic 1873 Single Action Army. The fanfare of the M1911 shows no sign of abating.

To understand firearm development, it is necessary to have some knowledge of the economy during their progress. The Civil War brought about a great increase in economic opportunities—hence industrialization—to the Union. Manufacturing business grew at a phenomenal rate. The war created a huge market for firearms and fueled the development of their technology. While the waging of war created the demand, it was the Reconstruction period after the war that brought about a maturation of that booming economy. The U.S. military—primarily the army at that time—needed better firearms with which to serve the country.

Single-shot and repeating rifles fed by cartridges that were ignited with a primer pressed into the center of the rear of the case replaced cap-and-ball muzzleloaders and rimfire-primed cartridges. Revolvers—which had progressed nicely into the cap-and-ball technology—began seeing their own cartridge development to centerfire-primed rounds. They were very popular with the cavalry because they could be operated with one hand and offered as many as six shots before requiring a reload.

Colt rather quickly came out with a Benet-primed .44 Colt cartridge for its Richards-Mason conversion of the 1860 Army. The actual diameter of the heeled, outside-lubricated bullet was .451″to .454″, and it featured a 225-gr., conical lead bullet in front of 23 grains of FFg blackpowder for a velocity of 640 f.p.s. and 207 ft.-lbs. of energy. Charles B. Richards, an engineer at Colt, and William Mason, a gunsmith who came to Colt from Remington in 1866, worked together on the .44 Colt cartridge, which was introduced in 1871.

The Richards-Mason conversion was a stopgap measure as the company retooled and set up to manufacture what would become the Colt Model 1871-72 Open Top revolver. This revolver was chambered in the more powerful .44 Henry Rimfire cartridge, a major step up in power from the .44 Colt. It was capable of kicking a 200-gr. conical ball bullet out at 1,125 f.p.s. with 568 ft.-lbs. of energy, though these numbers are probably from a rifle.

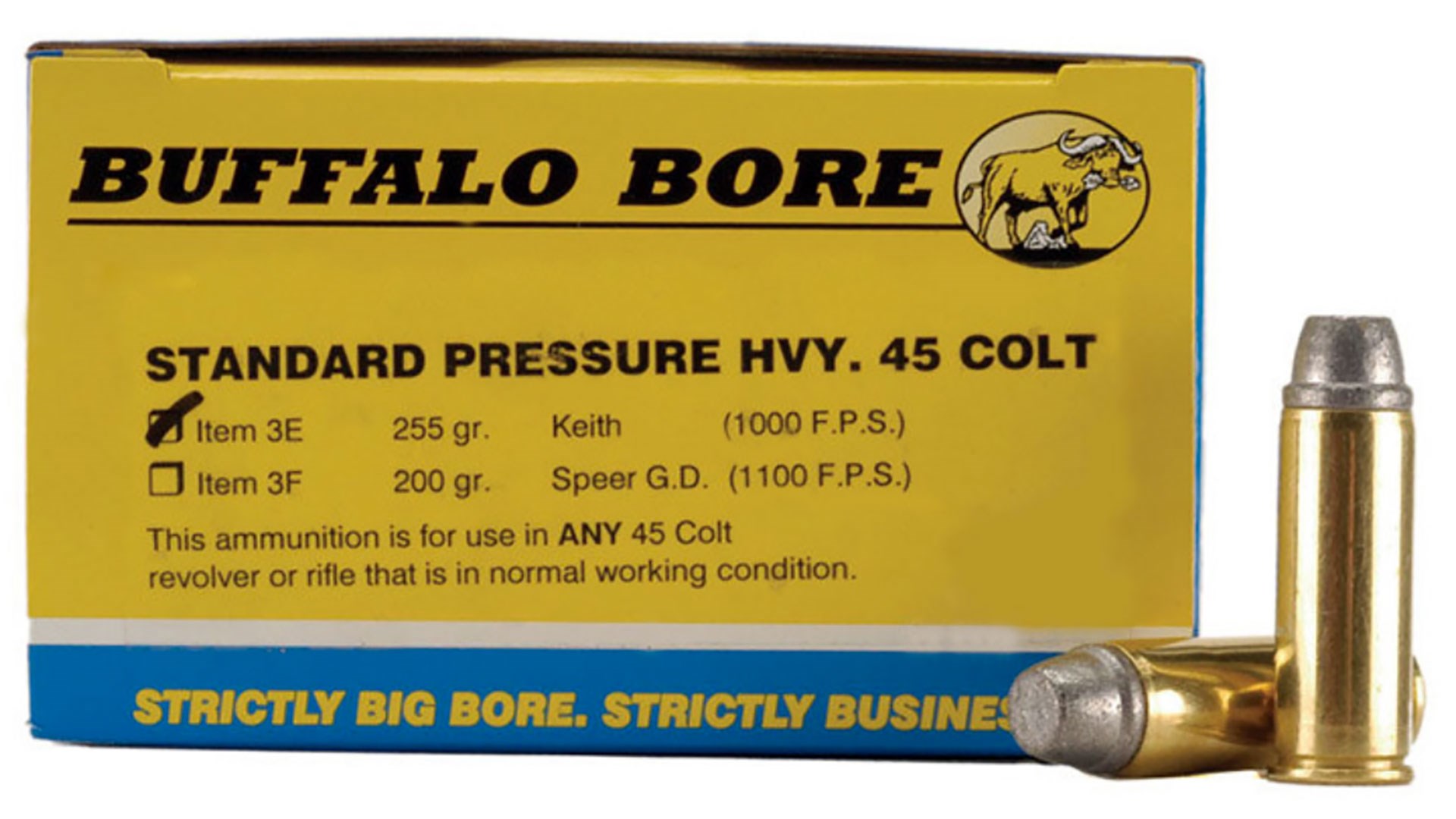

Buffalo Bore .45 Colt available today loaded with a 255 gr. lead bullet.

Buffalo Bore .45 Colt available today loaded with a 255 gr. lead bullet.

Nonetheless, the army bought several thousand of them for its cavalrymen during the revolver’s two-year production run. Three things became very clear. The army wanted a more powerful revolver. It did not want outside-lubricated bullets that pick up dirt and grit from the field. And a revolver tough enough to stand up to these rigors must have an enclosed window for the cylinder, what we now refer to as a solid frame.

Richards and Mason began developing a new revolver and teamed up with ammunition engineers at Remington to manufacture the cartridges. Both the revolver—the 1873 Colt Single Action Army(SAA)—and its cartridge, the .45 Colt, would become iconic in the annals of firearm development. The .45 Colt retains the bullet diameter of its .44 Colt predecessor at .452″ – .454″ but kicks the weight of the bullet up to 255 grains.

After playing with loads with bullets as light as 225 grains and powder weights from 28 to 40 grains, they settled on the 255-gr. bullet in front of 40 grains of FFg blackpowder for 840 f.p.s. with about 400-ft.-lbs. of wallop out of a revolver. Production of ammo and revolver began in 1873. The army quickly saw the improvement of both revolver and load, as did civilians, and the Colt .45, as it became commonly called, generated a great reputation as a man-stopper.

All of the preceding did not occur in a vacuum. Smith & Wesson had been hard at work on its No. 3 revolver in .45 caliber. In fact, the army adopted the No. 3 in 1870 chambered in .44 Smith & Wesson American. But the brass wanted more power. Major George W. Schofield had an engineering improvement to the Model 3. Instead of mounting the spring-loaded barrel latch on the barrel, he reversed it and mounted the latch on the frame.

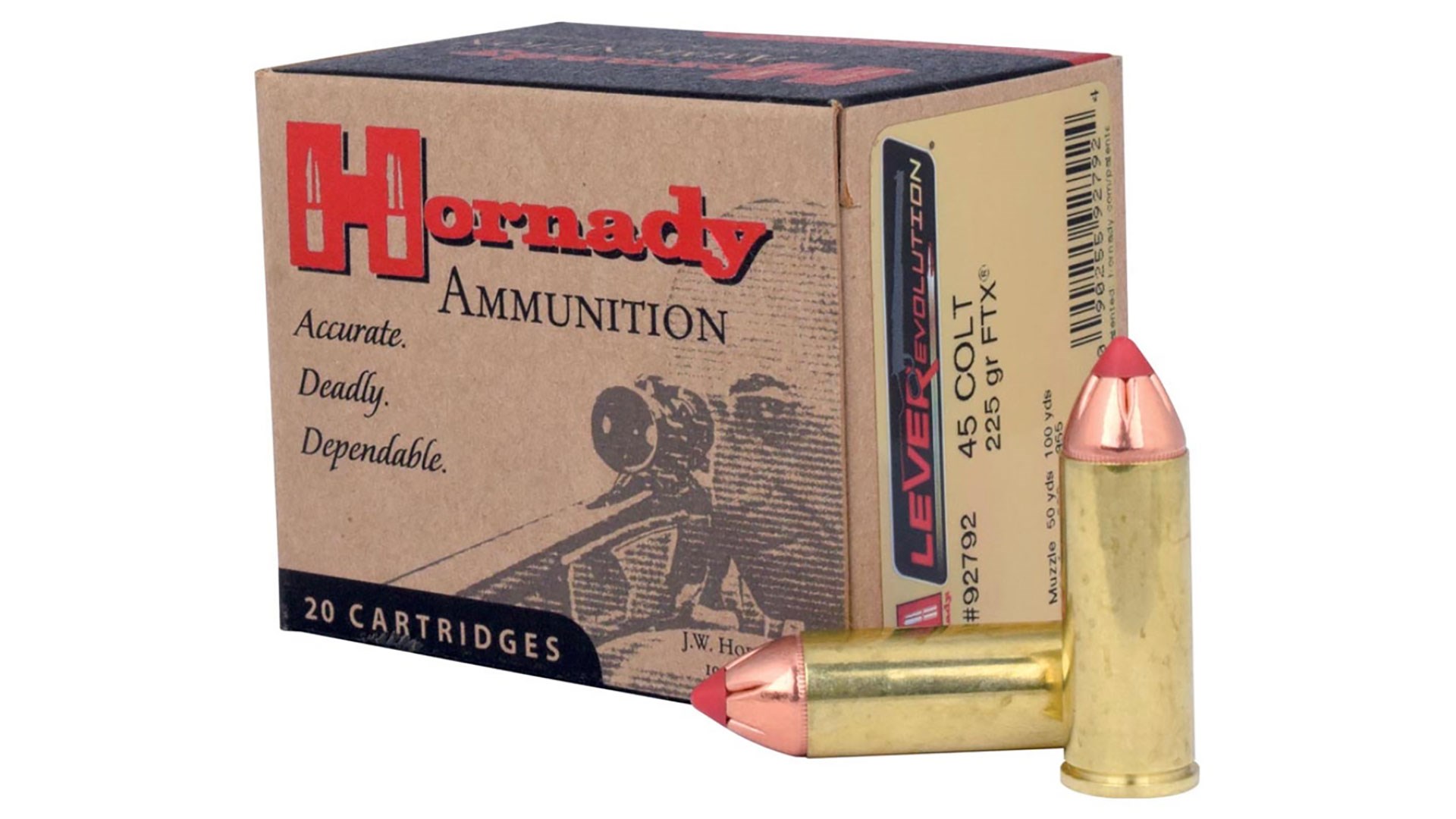

Hornady .45 Colt cartridges loaded with a .255 gr. FTX bullet.

Hornady .45 Colt cartridges loaded with a .255 gr. FTX bullet.

The army specified that the revolver would chamber the .45 Colt cartridge, but the Smith & Wesson revolver’s cylinder was too short do it was chambered in a shorter .45 Smith & Wesson—often referred to as the .45 Schofield, adopted in 1875. The Smith & Wesson cartridge would function in the Colt SAA but not vice-versa. Army quartermasters had headaches trying to sort out ammo for each revolver. Frankfort Arsenal, which supplied nearly all the ammo for the Army, simply ceased loading the .45 Colt and supplied the troops with .45 S&W cartridges.

Somewhere in all of this the .45 Colt nomenclature was colloquially changed to “.45 Long Colt” to differentiate it from the shorter S&W cartridge. From bank heists to battlefields, train robbers to shopkeepers, the .45 Colt and the SAA was king. Sure, there were plenty of those finely made Smith & Wessons, but out on the frontier far from gunsmiths, people counted on the robustness of the SAA and its man-or-beast-busting .45-cal. cartridge.

They must have done something right because, 147 years later, the cartridge continues to be loaded. Other than in wartime, there hasn’t been a hitch in production of the .45 Colt cartridge. The military could not leave well enough alone. Some 21 years after the introduction of the Colt SAA and its .45-caliber round, the military adopted the Model 1892 Colt double-action revolver chambered in a .38 Long Colt cartridge developed in 1875, featuring a 150-gr. lead, round-nose bullet launched by blackpowder at 708 f.p.s. with a measly 157 ft.-lbs. of energy out of a 6″ barreled revolver.

Sometime later, a smokeless powder load sent a 148-gr. bullet downrange at 750 f.p.s. and 185 ft.-lbs. of energy. Some bad experiences in the Philippines during the Philippine–American War of 1899–1902 against Moro juramentados tribesmen had the army scrambling for anything that could fire .45 Colt cartridges. This led to Colt developing the M1909 round , identical in load to the original .45 Colt round but with a larger rim to accommodate the star-like extractor/ejector of the New Service double-action revolver.

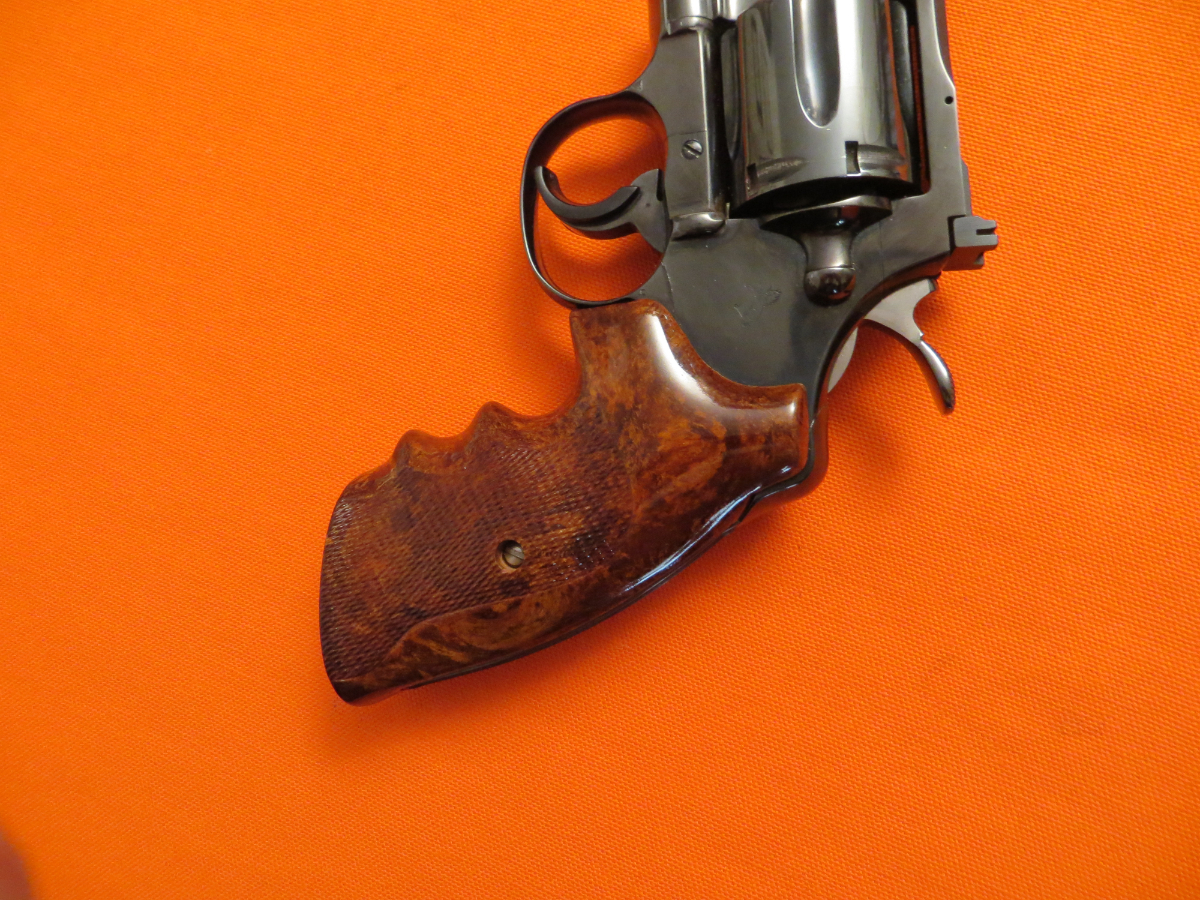

The author’s Ruger Blackhawk chambered for .45 Colt.

The author’s Ruger Blackhawk chambered for .45 Colt.

M1909 ammunition will not work in single-action revolvers chambered in .45 Colt because the rim diameter interferes with adjoining cartridges. Even as semi-auto pistols began emerging, the .45 Colt has remained a steady-selling cartridge. Two reasons for that is the reliability and longevity of the SAA revolver and the fact is that it plain works.

Whether dealing with desperados, deer or even black bears, in the hands of a decent shot, a man armed with a .45 Colt will go home to his family or bring home the game. In the mid-1950s, a Utah-based gunsmith and experimenter named Dick Casull began exploring the limits of what a .45-cal. handgun could produce. He started with blackpowder-framed Colt SAAs, re-heat treating the frames and converting them to five-shot cylinders.

In 1959 he introduced the .454 Casull cartridge featuring a case 1.383″ long—some .098″ longer than a .45 Colt case—and a thicker web in the head of the case that Casull claimed to get more than 1,900 f.p.s. with a 250-gr. bullet. The power guys went nuts over this, but it would take almost 25 more years before this cartridge would be commercially loaded and have a factory manufacture a revolver that could handle it. In the meantime, Ruger chambered its tough Blackhawk revolver in .45 Colt, as did Thompson/Center in its equally solid Contender single-shot pistol.

Power guys ignored the loading manuals of the day and began dropping huge charges of slow-burning powders into .45 Colt cases to see what they could get away with. Now called T-Rex loads by the brethren, many loading manuals gave loads for these guns expressly and specifically. As for me, if I want an extremely powerful revolver—which I do not anymore—I would choose a cartridge expressly made for those tasks. I like the .45 Colt for what it is: a moderately powerful handgun cartridge that does anything I might ask from a handgun.

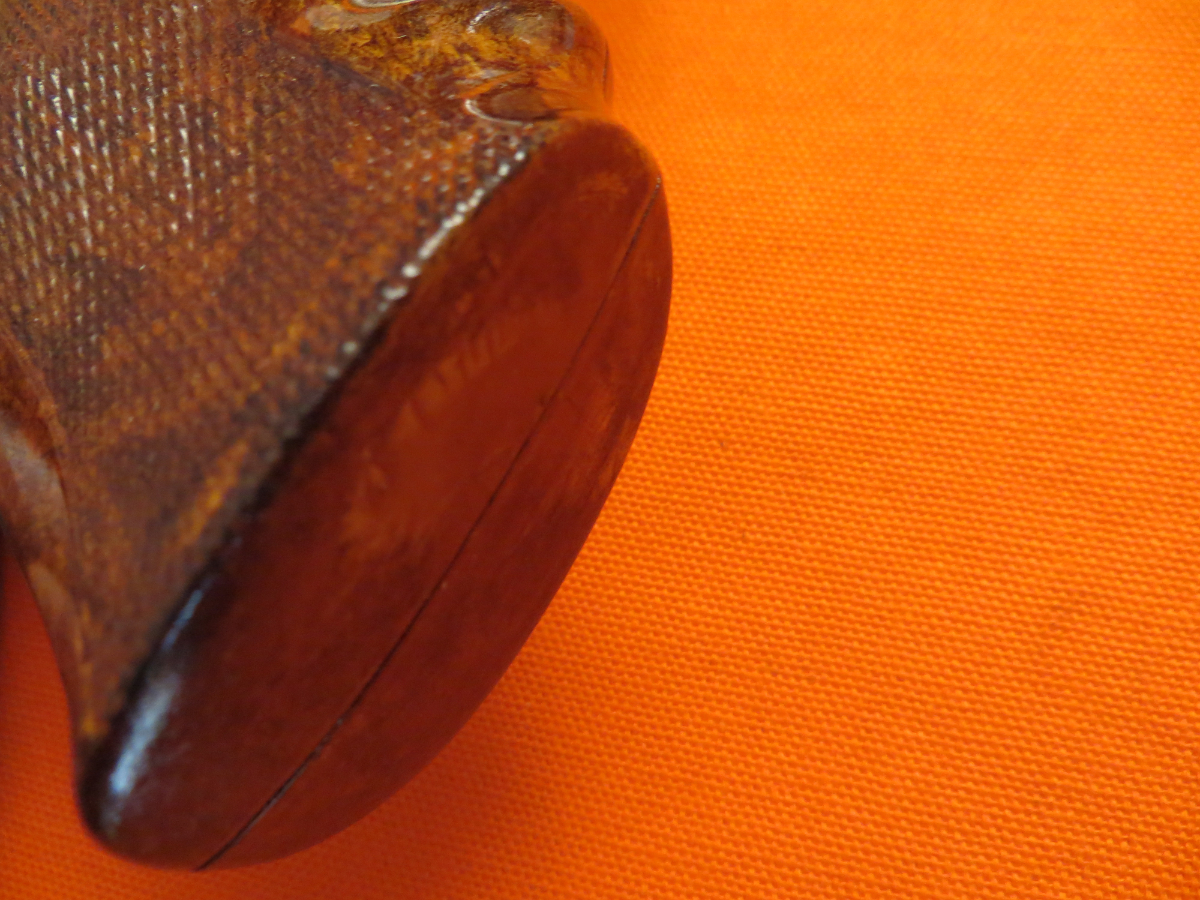

A view from the muzzle end of the author’s Ruger Blackhawk chambered for .45 Colt.

A view from the muzzle end of the author’s Ruger Blackhawk chambered for .45 Colt.

As with all my revolvers, save my J-frame Smiths, I prefer to cast hard semi-wadcutters at some 258 grains in my .45-cal. with 9.0 grains of Alliant Unique powder. In my 4 5/8″ Ruger, it gives me about 912 f.p.s. with 476 ft.-lbs. of muzzle thump. If I need more thump, I’ll choose a rifle—too many years of shooting those big bruisers has left me with some arthritis in my hands.

All the major factories load the .45 Colt cartridge today; one of the smaller manufacturers—Garrett, in Texas, loads +P .45 Colt rounds that are expressly for the Rugers. But there are plenty of JHP and SP loads available—outside of the pandemic-induced ammo shortage. There are even relatively soft-recoiling loads for cowboy action shooters. It is the cowboy action shooters that brought another firearm into the .45 Colt fold—rifles.

When the cartridge was introduced, the small diameter and thin rim of the .45 Colt cartridge, along with the straight-walled case, would not feed or extract reliably in the lever-action rifles of the day. Too, it was fueled with blackpowder, which leaves a rather heavy residue. A straight-walled case would often hang up because of that following, especially if the residue was exposed to dampness.

Today, however, Winchester, Uberti, Henry and Cimarron have produced replica lever actions chambered in the big 45. Smokeless powders, some engineering tweaks and the clientele who keep their competition guns clean has largely neutered the old attitude toward .45 Colt lever actions. Continuously produced for nearly 150 years, both in ammo and guns, the .45 Colt remains a capable cartridge for field use or even self-defense. I know several fellows who regularly have a single-action revolver on their belt on a daily basis, and that revolver is a .45 Colt.

By John B. Snow Photographs by Bill Buckley

In celebration of its 100th anniversary, Griffin & Howe decided to build a small number of rifles worthy of the occasion. As you can see in the photographs, they are stunners—but there’s more to these beauties than meets the eye. These inspired creations commemorate not only the founding of the illustrious gun company but also its special connection to Townsend Whelen and Outdoor Life.

That’s a lot to take in, so allow me to dial the clock back to the early decades of the 20th century.

Whelen—most often referred to as Colonel Townsend Whelen— was a career Army officer who loved hunting the wilderness and had a deep appreciation of fine rifles, ballistic innovation, and the art of precision marksmanship. He communicated these passions with a clear, straightforward writing style that earned him a wide following and eventually the unofficial title of dean of the outdoor writers.

His most enduring legacies are the statement that only accurate rifles are interesting — which was the title of a story he wrote for American Rifleman in 1957—and the cartridge that bears his name: the .35 Whelen.

Little surprise that a man of his (ahem) caliber was one of the first shooting editors of Outdoor Life, a position he held for many years before passing the mantle to Jack O’Connor.

By way of context, since 1898, the year of OL’s founding (we’re celebrating our 125th anniversary this year), we’ve only had five shooting editors. In order, they are: Charles Askins Sr., Col. Townsend Whelen, Jack O’Connor, Jim Carmichel, and your humble correspondent.

THE GENESIS OF GRIFFIN & HOWE

Whelen started writing for Outdoor Life around 1906 and contributed to the publication well into the 1930s. At some point during the 1910s, he caught wind of a talented stock maker, Seymour Griffin, who had built a reputation for turning homely government-issue Springfield 1903s into lovely sporting pieces.

Whelen was already an influential force in the development of sporting and military arms and munitions by that time. His day job was director of research and development at Springfield Armory and commanding officer of Frankford Arsenal.

In 1921, Whelen met James Howe, a gunmaker and foreman of the Frankford Arsenal machine shop. Together they started working on a new family of cartridges based on a .30/06 necked up to different diameters, including .400, .375, and .35. Of these “Whelen” cartridges, only the .35 Whelen made significant inroads with the shooting public—and even so, it remained a wildcat from 1922 until 1988, when Remington finally offered it as a commercial load.

Whelen introduced Griffin and Howe and urged them to go into business together. Acting as an official advisor, he helped them procure financing.

Griffin & Howe, a sporting goods store and custom gunmaker, opened on June 1, 1923, at 234 East 29th Street in New York City. Though his name isn’t on the company’s trademark, Whelen is rightfully acknowledged as one of Griffin & Howe’s founders.

The business quickly grew, and Griffin & Howe developed a worldwide reputation for making fine hunting rifles; it soon became one of the premier sources for hunters and sportsmen looking to get outfitted for adventure. Its clientele included Ernest Hemingway, Robert Ruark, Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, Bing Crosby, President Dwight Eisenhower, and other luminaries.

Over the past 100 years, the company has had its share of ups and downs but continues to endure. Today, its home base is Hudson Farms in Andover, New Jersey, and it is under the directorship of company president and CEO Steven Polanish.

A PERFECT PAIR

About eight years ago, Griffin & Howe expanded its rifle line with the introduction of the Long-Range Precision Rifle and since then has added the Highlander and All-American models.

The rifles here are Highlanders, which are built on control-round feed actions produced by Defiance Machine and have a classic three-position safety mounted on the bolt shroud.

Both rifles are chambered in .35 Whelen, naturally, and blend traditional design elements with interesting innovation.

Because of Whelen’s role in getting Griffin & Howe off the ground and his position at Outdoor Life, OL and G&H have always enjoyed a strong connection and friendship. It’s a relationship that’s lasted throughout the decades and is the reason I was able to get a first look at these special guns.

UNIQUE SIGHTS

The carbon-fiber barrels, which are made by Proof Research, may have caught your eye. They were constructed to accommodate an island rear sight, which, to the best of my knowledge, has never been done on a carbon-fiber barrel before, and certainly never as a standard offering.

These sights are a thing of beauty. They’ve been regulated to hit spot-on at 100 yards and have a single leaf that flips up for 200- yard shots.

While I spent a lot of time shooting these rifles for accuracy off the bench with the Swarovski Z8i 1-8x24s they came with, I couldn’t wait to pull the optics off—both rifles feature Griffin & Howe’s proprietary quick-detach scope mounts—and run them with open sights.

I was able to easily ring the 10-inch gong at 100 yards with every shot. The bead on the front post is protected by a sturdy shroud and settled nicely into the notch of the shallow “V” formed by the rear sight. A vertical white line running up the middle of the

rear sight helps the shooter center the front bead precisely in the notch.

When I moved to 200 yards, it took me a couple shots to spot my bullet impact—I was hitting a bit high—but I made the adjustment and went two for three at that distance.

In my mind’s eye I was no longer at a shooting range, but rather I was hunting in East Africa back in the 1950s, putting down a Thomson’s gazelle for camp meat or stalking close to a kudu bull crowned with horns spiraling toward the heavens.

Not many rifles can transport a shooter that way, but these do. A rifle bearing the Griffin & Howe name, chambered in the Whelen, and topped with nothing more than crisp and effective open sights, was something to aspire to back in the day. It still is.

WONDERFUL WOOD

The rifle with the composite stock is built for hard work and is pleasant enough to look at for a gun of that type, but it pales in comparison to the glorious wood on the other rifle.

The French walnut that Polanish selected—he purchased both of these rifles, which have serial numbers GH35000 and GH35001— is a great canvas on which to showcase the stock maker’s art.

The stock maker in question is Dan Rossiter, the shop foreman at Griffin & Howe and a member of the prestigious American Custom Gunmakers Guild.

The hand-cut checkering is perfect, with the diamonds on the fore-end and grip in line with the border, as it is supposed to be.

The raised Monte Carlo cheek piece, with its negative comb, is outlined with a sharp and attractive shadow line. The ebony tip on the fore-end and leather recoil pad bookend the highly figured wood, completing the elegant execution of the stock.

The grip was cut with a slight palm swell. It isn’t enough to distract from the rifle’s classic lines, but it is a nice modern ergonomic enhancement that shows how the old and new can coexist in a modern hunting rifle.

FLAWLESS FIT AND FINISH

I handed the rifle at one point to a friend of mine in his early 30s who is an accomplished long-range shooter and knows his way around modern precision rifles—and, in fact, builds them for a living. But he’d never seen a rifle like this and was puzzled by the seamless fit between the stock and barreled action.

He asked whether that was normal, and it drove home how mating a stock and action this way has become a relic of another era. Free-floating barrels isn’t new—Whelen was advocating it decades ago—but it has become so ubiquitous that the old-school technique of tight stock fitting has all but disappeared.

That level of fit and finish is evident everywhere else on the rifle, too. The inletting around the bottom metal, the ejection port, the grip cap, the tang—all of it is done to less than a hair’s width of tolerance.

One thing worth mentioning is that the Torx-head guard screws are going to be replaced with proper slot-head fasteners soon. In the hurry to get the rifle ready for my hunt, that small corner was cut.

NEXT LEVEL ENGRAVING

The wood stock and carbon-fiber barrel create the initial visual impression of the rifle, but as soon as you get close to it, what really stands out is the adornment on the metal.

One of the things that’s so appealing about this rifle is that it is a family affair. Chris Rossiter—brother of stock maker and shop foreman Dan—is also a member of the ACGG and did the engraving.

All told, Chris put 198 hours of meticulous handwork into the rifle using hammers and fine-pointed chisels that, depending on their shape and local custom, are known as burins, gravers, tints, or spitstickers. Every metal surface on the Highlander has some

engraving and each is delightful to behold.

The engraving on the magazine floorplate is particularly intricate. It features a portrait of a bighorn sheep—which has been part of Griffin & Howe’s logo since day one—surrounded by vines and scrollwork and framed within a border consisting of elegant curving lines.

The vines and pattern of wavy lines are repeated on other sections of the rifle. The deep relief on the right side of the action is simply amazing, though, in fairness, that description applies to all the engraving.

From a personal standpoint, I also greatly admire the lettering on the rifle. The bold “Griffin & Howe” engraved on action is done in a gorgeous font that reflects the art deco aesthetic that was in vogue when the firm was founded in 1923.

Much of the rifle is still in the white, which really shows the engraving to full effect, but some elements have been color case hardened. The scope rings, scope bases, front and rear sights and grip cap got that treatment.

Mixing those colors and textures isn’t exactly traditional, but it does showcase Griffin & Howe’s rifle-building chops in a dramatic fashion.

Of course, no two of these rifles will be the same. Griffin & Howe is making only 10 of the wood and 10 of the composite stocked models, and each will be built according to the customer’s preference. That includes choice of wood, stock dimensions, type of recoil pad, and style and quantity of engraving.

IN THE FIELD

In one of the more audacious moves of my career, I decided to take these Highlanders hunting. The wood stocked Highlander has a base price north of $20,000 and a bit more than that in the engraving, for a total cost of $44,000, give or take. By comparison, the synthetic stocked version is a budget gun at $12,400. I’ve never hunted with a pair of guns as costly, but that didn’t stop me from loading them into the back of my pickup and driving 1,000 miles north from Montana to a remote area near Alberta’s Lesser Slave Lake.

On the drive to camp I picked up Steven Polanish at the airport in Edmonton and we continued on our way to chase bears with John and Jenn Rivet, who own Livin the Dream Productions.

We spent a week in the woods, a thick mixture of poplars, birch, and spruce, watching bears from tree stands and ground blinds during the long northern evenings.

Polanish shot a bear of a lifetime during the hunt—a huge color phase cinnamon bear that squared more than 7½ feet. My bear, a 7-footer, was no slouch either.

It will come as no surprise to anyone who has experience with the .35 Whelen that the rifles and cartridge performed well. Both of our bears were flattened with one shot and hardly moved.

The ammo we used was Barnes factory 180-grain TTSX FBs. The shots in this country aren’t far—anything more than 25 yards would qualify as a poke—so the bullets are carrying nearly every bit of their velocity upon impact. From the wood gun, muzzle velocity averaged 2941 fps, while the barrel on the synthetic gun was

a touch faster at 2961 fps.

Those tough monometal bullets passed through both bears, leaving exit holes that indicated impressive expansion.

The recoil generated by the rifles is a bit more than what you’d get with a .30/06. Shooting 20 or 30 rounds at the range isn’t cumbersome, but with longer range sessions, the kick of the .35s will wear down your shoulder.

That’s the price, however, for a hard-hitting medium-bore cartridge like the Whelen, and that’s why it is an excellent choice for elk and other large game.

A LONGSTANDING LEGACY

With the creation of these rifles, Griffin & Howe has done an impressive job memorializing the milestone of their 100th year and the contributions Townsend Whelen made to their success.

In my own nod to tradition, I’m going to engage in the time-honored practice among gun writers of contrarianism.

Whelen got most things right, but when he said only accurate rifles are interesting, he missed the mark. Jim Carmichel and I discussed this point years ago over martinis, and we agreed that inaccurate rifles are often more interesting because they present

a problem to be solved—and the process of coming up with a solution makes the gun writer’s profession fascinating indeed.

But whether a rifle is interesting hinges on more than if it places bullets in precise clusters, and I think these rifles are proof of that. They are both accurate and capable of leveraging everything the .35 Whelen brings to the party in terms of exterior and terminal ballistics. But, really, that’s not the yardstick by which they should be judged.

They are expressions of the highest form of the traditional gunmaker’s art but executed with nods to modern trends and sensibilities that are surprising and refreshing to see. The blend of old and new contained within the format of barrel, action and stock that is as familiar to riflemen as their reflection in a mirror is a remarkable achievement.

I don’t know if I could change Whelen’s mind on his assertion. We ballistic scribes tend to stick to our guns, literally and figuratively. But if nothing else, he was always forward thinking with respect to rifles and marksmanship and had, dare I say it, a progressive mind when it came to innovation.

I know he would feel humbled and honored if he could hold and shoot these rifles. Despite his remarkable achievements, Whelen was never one to put on airs. And once he got a closer look and could see what went into their crafting, I’d be shocked if he didn’t say to himself, These are…interesting.

Somebody say Colt Python?

Lesson: The rule is, “You don’t have to be right, but you do have to be reasonable.” You can be cleared four times over in a shooting and still be criminally charged. If you’re a cop criminally charged, we hope you belong to a union or fraternal organization.

A furtive movement shooting occurs when someone appears to be going for a gun, gets shot for it and turns out not to be armed. Sometimes the movement is a deliberate faking of the menacing gesture — to intimidate a victim or to achieve “suicide by cop” — and sometimes, it is unintentional.

For peace officers and armed citizens alike, the green light to use deadly force normally turns on only in a situation of immediate, otherwise unavoidable danger of death or great bodily harm to oneself or some other innocent party. For that situation to exist, three criteria must be simultaneously present. They are most commonly known as ability, opportunity and jeopardy.

The ability factor, sometimes called means, translates as “power to kill or cripple.” The opponent must be reasonably perceived to be either armed with a deadly weapon such as a gun, knife or club or have such a great unarmed advantage over you as to constitute disparity of force. This might take the form of greater size and strength, force of numbers or known or obviously recognizable skill in unarmed combat. The opportunity factor means they are close enough to employ that power to kill or maim quickly. Finally, the jeopardy factor is the element of manifest intent: The opponent must manifest, by words or actions, what would be reasonably interpreted as intent to kill or cause great bodily harm.

The furtive movement goes to the ability element. It gives the defender reason to believe the opponent is armed with a deadly weapon. It must happen in such a way the reasonable person would construe it as going for a weapon and nothing else within what the courts call the totality of the circumstances. The opponent must still be close enough to harm you with the weapon you reasonably believe they are armed with and must still be manifesting an intent to hurt or slay.

For perspective, why is the charge “Armed Robbery” when the perpetrator robs a bank with a note that says, “I have a gun, give me all the money” or simply has a hand in a pocket making a “finger gun,” but turns out to have no actual weapon? It is because his actions have given the victim reason to fear being unlawfully shot. The same furtive movement principle is in play if the intended victim draws a gun and shoots the suspect making said movement.

Please bear all of this in mind as we look at the United States v. Richard Palmer case.

The Stage Is Set

Deputy Richard Palmer had served with distinction as a uniformed law enforcement officer for more than 20 years, most of it with the Lake County Sheriff’s Department headquartered in Tavares, Fla. The agency comprises more than 500 sworn deputies and some 260 non-sworn personnel. On the night of October 11, 2016, Palmer was on routine patrol when he received a call of a disturbance at a known drug house in a rural part of the town of Paisley. As he headed to the address, he remembered a brother officer who had been murdered near there not long before.

Approaching the narrow road which led to the house, Palmer saw a Mercury sedan with a lone female at the wheel approaching from that direction. She blew through the stop sign and came to a halt directly in front of his marked unit. His first thought was that she was fleeing the scene; he obviously needed to talk to her. Palmer already had his windows down so he could hear any danger signals as he approached, and he saw her window was down, too. As she gestured apologetically, he gestured back for her to pull over and told her so loudly.

Instead, she accelerated away from him.

Palmer spun the steering wheel and followed, carefully avoiding two bicyclists, the only other people in sight. The woman drove less than a hundred yards and then suddenly cut left, across the lawn of a house, and came to a stop in the yard. Palmer followed, throwing the patrol unit into park and making sure it was angled to the left to put the engine block between her and him.

He saw the driver’s door pop open. Alarm bells went off in his head. When a driver does that, it’s telling the officer behind them there’s something in their car they don’t want the cop to see. It is also, Palmer knew, one of the most common patterns of ambush murder during traffic stops.

There had been no time to radio in. Palmer quickly opened the door of his unit, stepping to the left for an angle to better see the driver. What he saw chilled him: She appeared to be putting a black semiautomatic pistol into the front pocket of her hoodie with her left hand.

She approached him rapidly, her hands now visible. Palmer’s department-issue GLOCK 22 was out and in hand, muzzle down, as he yelled at her repeatedly to stop. But she kept coming.

The Unforgiving Moment

The hands are where he can see them … and then suddenly they drop, the left hand appearing to be going for the hoodie pocket. Palmer raises the GLOCK, leveling on her chest, and fires. The woman jerks and then falls heavily to her right. The hands are visible again and empty. Palmer ceases fire.

He moves forward. GLOCK still pointed at her, the deputy tries to remove the gun from the hoodie pocket.

He finds only an iPhone. He tosses it to the side. It is at that moment he realizes she is unarmed.

Immediate Aftermath

The woman, whom we will refer to here as only RP — yes, she had the same initials as the deputy who shot her — survived. The bullet struck her right hip from about 20′, dropping her instantly. She would complain of permanent pain thereafter.

The dashboard camera had been set slightly to the right of center in the patrol car, several feet from where Deputy Palmer was standing when he fired the shot in question. Its time counter showed less than one minute from when she accelerated away from the patrol car at the intersection to when she was shot.

In the silent video, RP gets out of the car. She has an apologetic smile as she walks toward the patrol car and her hands are chest high. Suddenly, both hands dip down toward her waist. The hands rise again, and an instant later, she is seen to collapse down to her right from the gunshot. Palmer is seen approaching from the left, GLOCK still covering her, and immediately going to her left hoodie pocket. He is seen to withdraw the smartphone and toss it aside. He then holsters, attempts to handcuff her and finds it is causing her too much pain. He abandons the handcuffing and radios for paramedics and backup.

Investigative Aftermath

It was clearly a furtive movement shooting. We’ve all heard the term “justifiable shooting.” It means the shooter did the right thing by pulling the trigger. As the late Judge Roy Bean might have said, “That person needed to be shot.” Less widely known is the concept of the “excusable shooting.” That conclusion says, “With 20/20 hindsight and unlimited time, we now know that the person in question didn’t need to be shot. However, the circumstances were such that any reasonable person might have done the same as the shooter, and therefore, the shooter should be held harmless (i.e., not be convicted of, or punished for, the shooting).” This incident fits the latter profile.

The Lake County Sheriff’s Office concluded so. Rick Palmer was restored to duty and was later promoted to a supervisory position.

FDLE, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, also investigated the shooting. That agency has a reputation for not covering for bad cops. They found no wrongdoing on Palmer’s part.

The State’s Attorney’s Office reviewed the shooting and found no problem with it.

Indeed, a Grand Jury assessed the matter and returned No True Bill, which in essence is a finding that no crime has been committed.

However, much later, the incident came to the attention of an attorney in the United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division. He thought otherwise. In September 2019, Palmer was indicted on Federal charges of violating RP’s civil rights and lying to investigators.

Trial

The trial was held in Federal Court in Tampa from the end of March through early April 2022. The competent Alan Diamond and Kepler Funk were co-counsel for the defense. Palmer had hired them out of his own pocket. Never thinking anything like this would happen to him, Palmer had never joined the Fraternal Order of Police. The prosecution’s theory was Palmer had become angry with RP for not pulling over and shot her for that reason.

Sheriff Payton Grinnell was called to the stand. On direct, he answered yes to the prosecutor’s questions that department regulations called for the officer to radio in the stop and turn on emergency lights that would activate sound recording on the dashcam, which Palmer had not done. However, on cross-examination, the sheriff explained the regulations in that regard were guidelines, not laws.

RP herself was not called by the prosecution to testify. Only the prosecution can say why. Had she taken the witness stand, she might have had to admit to the alcohol and narcotics in her bloodstream that night and that she’d had many arrests often involving methamphetamine and had done jail time. It would probably also have come out she had previously testified she had pulled into a stranger’s yard because she knew she was driving someone else’s car without their permission and without a driver’s license. She somehow believed the car wouldn’t be towed if it was on private property. This would have killed the Government’s insinuation she didn’t know she was being stopped by the police. Because Palmer didn’t know her background at the time of the stop, it could not be introduced by his defense attorneys.

The defense’s case was brief. As an expert witness for the defense and having intensively debriefed Palmer, it was easy for me to counter the prosecution’s assertions.

Why didn’t Palmer turn on the emergency lights or siren? Their purpose is to notify the target driver and others on the road a stop is taking place. The video showed clearly the two bicyclists saw Palmer and stayed out of his way and that RP could clearly see the marked car, the uniformed officer, and hear and see his directions to her. In the few short seconds of the interaction, he simply hadn’t had time to hit the now unnecessary toggle switch. The Government alleged he didn’t know the dashcam was running. In fact, Palmer had watched its installation and knew it was indeed operative. Why didn’t he radio in? He didn’t have time. He hadn’t been able to read the license plate, and the “chase” covered less than a hundred yards.

Part of the prosecution’s case theory was Palmer violated procedure by doing a routine traffic stop instead of proceeding to a more serious call for police service. I explained the woman blowing through the stop sign was the least of it: She appeared to be coming from the scene of the serious call, could be expected to provide critical information on what was happening there and might even be the perpetrator. Thus, stopping her was logical and a part of responding to the more urgent call.

The core question was, how could the shooting have happened? Despite access to top experts at the FBI and DEA academies and more, the Government hadn’t figured it out. RP’s sudden turn into the yard had given Palmer no time to radio for backup. Her emergence from the vehicle, appearing to put a pistol-like object in her pocket and her rapidly approaching him in defiance of his orders to stop all warranted taking her at gunpoint. Her hands coming down to where she had appeared to have stowed a gun triggered the shooting.

Timing

The Government’s video of the shooting, complete with a time counter, showed from the moment her hands started going down, they had reached the area of the hoodie pocket in 0.33 of one second. The movement caused Palmer to raise his gun, indexing on her chest. In an extended isosceles stance, his hands and pistol now blocked his view of her hands, which remained down for another 0.475 of a second. It took another 0.315 seconds for the rising hands to reach chest level — Palmer told me he never did see the hands come back up. By then, the 180-grain Gold Dot .40 bullet was on its way. She reacted to the bullet wound only a fifth of a second after the hands reached chest level. Overall, only 1.32 seconds had elapsed from the downward movement of her hands that triggered Palmer’s decision to fire to when she crumpled from the bullet strike.

Once it appeared she was going for the gun, even if he had seen the rising hands, it would have been an unanticipated stimulus to stop a trigger pull already under way. While reaction to anticipated stimulus averages about a quarter-second, the cognitive response required for a reaction to unanticipated response averages over a second for most people and will rarely happen quicker than seven-tenths of a second at best.

Why not wait to see the gun? Because if you wait that long you’ll see what comes out of it. I testified once the hand was on the perceived gun, a person in RP’s position could have drawn and shot the deputy in less than a second.

The prosecution harped on the hip shot, implying it was intentionally fired to torture and punish and emphasizing police are taught to shoot center mass. I was able to testify the officer had told me (and the initial investigators) he was trying to put the shot center chest. However, I explained right-handed shooters such as Palmer tend to shoot low left (and southpaws, low right) due to “milking” the gun under pressure, which I demonstrated to the jury with Mr. Diamond. In a previous questioning, Palmer had been discussing this when he blurted he didn’t want to kill her; the Government seemed to interpret that as an admission to having shot her to torture her. Their theory did not explain why a rogue cop who wanted to torture someone with a bullet wound would leave her alive to testify against him.

I took the witness stand at about 10:30 a.m. and was done with cross-examination at about 2:30 p.m. Cross is easy when the truth is on your side, and you can explain it. On my departure, I learned the testimony I had expected from the defendant and department use of force instructor Richard Rippy had not taken place. Diamond and Funk felt it looked like we had covered the waterfront, and the jury had “gotten it.” In a “strike, while the iron is hot” decision, the defense closed after I left the stand.

To make a long story short, Kepler Funk delivered a brilliant closing argument in which he pointed out something I had established in my testimony: In the years since the shooting, the Government had had millions of times longer to second guess Rick Palmer than Palmer had when he reasonably believed he was about to be shot to death in the dark.

The jury acquitted him on all charges.

Months later, a Google search showed nothing whatsoever about his acquittal but still showed his 2019 indictment.

Palmer was welcomed back at the Sheriff’s Department with open arms and given a much-appreciated appointment to Marine Patrol, where he is now working.

Lessons

Action-reaction paradigms must be taken into account when analyzing cases of this type. They were, insofar as the Sheriff’s Office, FDLE and the State’s Attorney’s Office … but apparently not by the U.S. Department of Justice.

The guiding light for police use of force is the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1989 decision in Graham v. Connor. It focuses on the standard of objective reasonableness. The Court said, “The ‘reasonableness’ of a particular use of force must be judged from the perspective of a reasonable officer on the scene, rather than with the 20/20 vision of hindsight.”

The opinion also stated, “The calculus of reasonableness must embody allowance for the fact that police officers are often forced to make split-second judgments — in circumstances that are tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving — about the amount of force that is necessary for a particular situation.” Diamond and Kepler were able to get a jury instruction outlining this principle.

It is essential to have post-accusation support. Legal cases cost big money. I’ve always urged police officers to join their union or fraternal organization: It is the one entity that will likely pay for your legal defense if criminally charged. As much as the department might want to stand behind you, they’re not allowed to pay legal fees for people accused of crimes.

Organizations like Armed Citizens Legal Defense Network (ArmedCitizensNetwork.org) serve a similar purpose for private citizens. (Disclosure: I’m on ACLDN’s advisory board.) Rick Palmer paid about $100,000 out of his own pocket and Diamond and company gave him a hell of a deal at that.

Be sure your instructors will speak for you. Cop or armed citizen, a jury told you did what you were trained to do (and what you were trained was, in fact, the right thing to do) can be enormously helpful. Retired deputy Richard Rippy stood ready to do so. In this case, Rippy had briefed me on the training, and I was able to get it in. Some instructors fail to do so, particularly in high-profile or politically motivated cases.

I would like to publicly recognize Alan Diamond and Kepler Funk for a great job of lawyering and Richard Rippy and Sheriff Grinnell for being stand-up, honest lawmen. I would also like to applaud the trial judge, James D. Whittemore, who did a very fair and impartial job in what turned out to be his final case before retirement from a most distinguished career. Finally, a hearty thanks to Rick Palmer’s family — including one son in the same department — who stood by him all the way through the unnecessary nightmare it took more than half a decade to end.

As a dad I really cannot even imagine the agony of losing a child. The imagery of the aftermath of a school shooting is compelling beyond reason. In the face of such breathtaking tragedy, everybody everywhere wants to do something constructive to make it stop. However, effectively quelling such an egregious horror is a Gordian problem in the modern age.

Leftists apparently live in this surreal twilight zone. The most vocal among them believe that schools are safe spaces that can be made somehow miraculously free from violence solely by means of some fresh new legislative dictum. I want that, too. However, I also want to wake up every morning to a pile of gold nuggets sitting on my doorstep. Just because I want something a lot won’t make it so.

History’s Statistics On School Shootings

Schools have never been safe spaces. They just aren’t. There were three recorded school shootings in the 1850’s and another five in the decade that followed. The 1870s saw seven, while the 1880s had ten. Do you detect a trend?

By the 1970’s that number was up to 42. In the 1980’s there were 62. The 1990s had 99, and much of that was under an assault weapons ban. We endured a total of 298 school shooting episodes in the 20th century.

In the first decade of the new millennium, the number actually dropped to 80. However, we jumped to 252 in the 2010s. Thus far three years into the 2020’s we have had a further 133. Why is that exactly?

It’s not the gun, it’s the people

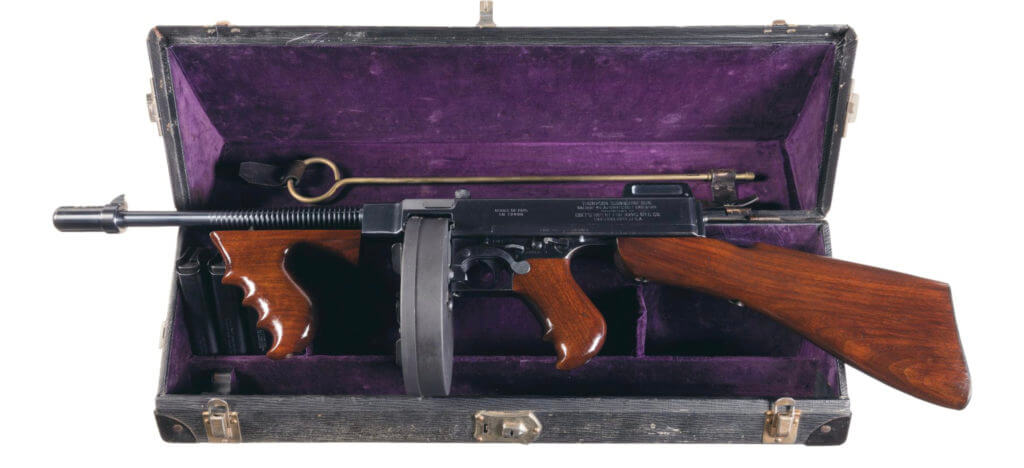

America is awash in guns, but America has always been awash in guns. Prior to 1934, there were literally no limits on the firearms you could own. Individual citizens could mount a cannon in their front yard or pick up a Thompson submachine gun at their local hardware store over the counter, cash and carry. It’s not the availability of guns. I would posit that today’s problem is the people.

The skyrocketing rates of school violence tend to follow our enlightenment as a society. Movies and video games have grown ever more violent. Murder or rape somebody in the real world and there are legal and moral consequences. However, watching murder or rape on the big screen or on your television is simply entertainment. There’s something intellectually incongruous about that.

At the same time, our society has steadily cheapened human life. Rates of abortion exploded after Roe vs Wade in 1973 (63 million in total to date), and now ten of our fifty states have legalized assisted suicide. Not debating the rightness or wrongness of those things in this venue. Simply observing a temporal correlation.

Plummeting Farther

We have also vigorously excised God from our schools and public spaces. As church attendance has plummeted, random violence and generally poor citizenship have exploded. Just as the absence of light is dark, the absence of God is godlessness. I suggest we might just be getting what we asked for.

The media would have you believe that the scourge of the school shootings perhaps began with Columbine. Back in 1999, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold traipsed into Columbine High School with a TEC-9, a Hi-Point 9mm carbine, an illegal sawed-off shotgun, 99 explosive devices, and four knives and proceeded to slaughter thirteen innocent people.

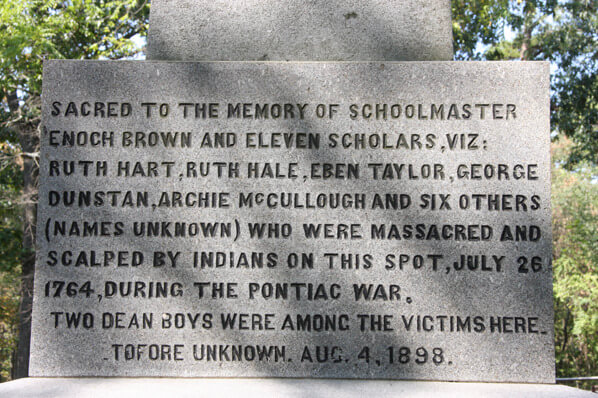

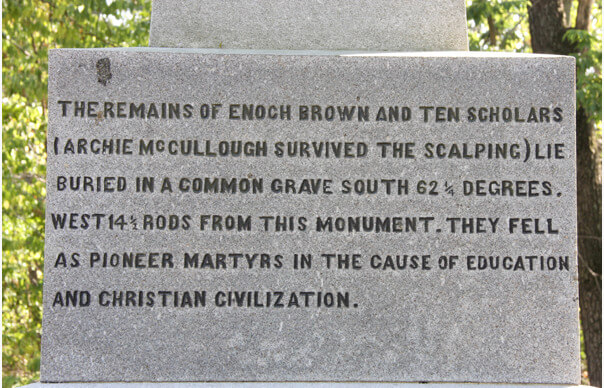

Those two freaking monsters will have all of eternity to atone for their crimes. However, Columbine wasn’t even close to when it all started. The Alpha school shooting took place in Franklin County, Pennsylvania, on 26 July 1764. Twelve years before we even became a nation, we had already had our first school massacre. Were I pressed to divine an explanation it would simply be that people are horrible.

The Setting of That First School Shooting

The American colonies in the mid to late-18th century were literally unrecognizable from what we enjoy today. The central government hailed from London, and what there was of civilized America was populated by rugged individualists who knew both hard work and discipline. As those early Europeans were busy carving a new homeland out of territory previously occupied by a wide variety of Native American tribes, conflict was inevitable. What follows was one of the most infamous events of what historians call Pontiac’s War.

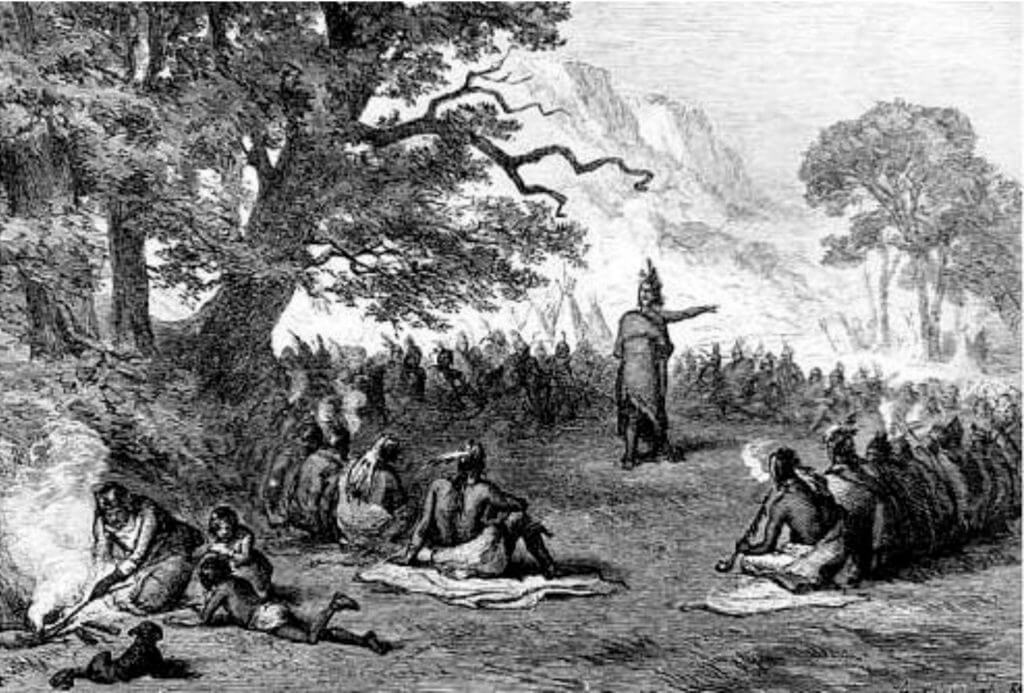

The French and Indian War had wrapped up the previous year, yet few of the participants were really thrilled with the outcome. A loose confederation of Native American tribes centered around the Great Lakes banded together to drive the British out of their lands. Recall that back then most of who we might view as Americans were loyal subjects of the British crown.

The Reality

It is tough for us modern folk to appreciate just how brutal things were during this time. History has sanitized much of the horror from the narrative, but there was more than enough atrocity to go around on both sides. The Indians kicked off this particular party by attacking British forts and murdering or enslaving hundreds of colonists. Prisoners were routinely killed, and the line between civilian and soldier seemed forever blurred. Along the way, both sides developed a white-hot hatred of the other. As has been the case since the very dawn of human history, humanity fractionated by race and each side slaughtered the other wholesale.

Being captured by the natives was all but unthinkable. Their capacity for torture was limited solely by the technology of the day. During one engagement while Fort Pitt was besieged by Native American warriors, British officers tried to infect the Indians with smallpox by means of contaminated blankets. Such biological warfare would be condemned in the strongest terms by most of the planet today. Back then it was just part of doing business.

The end result was a bloodbath. This raging venom drove those involved to some terribly dark places. One of those dark places was a schoolhouse in what is Newcastle, Pennsylvania, today.

The Massacre

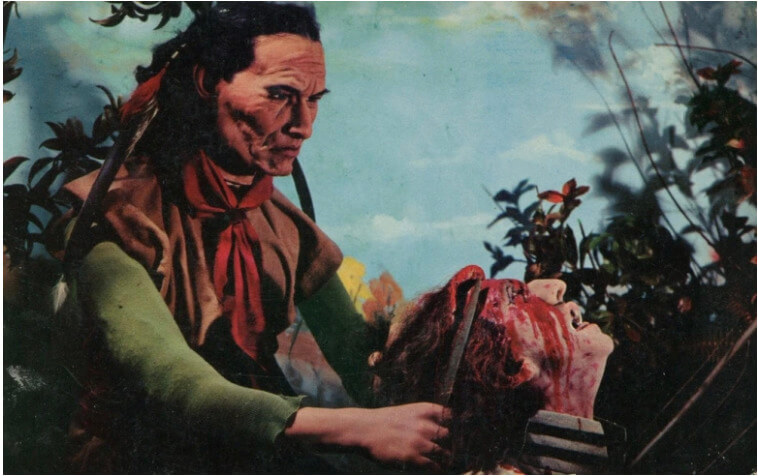

The carnage began the day before when four Delaware Indian braves encountered a pregnant white woman named Susan King Cunningham out walking alone. They clubbed her to death and then cut the fetus from her womb. The Indians later passed by the occupied home of a widow woman who had her windows boarded up against the weather. Presuming the house to be vacant they did not investigate. On 26 July 1764, these four braves made their way to the small wooden schoolhouse that serviced the area.

Inside was schoolmaster Enoch Brown and eleven students. School accommodated all ages back then, so the accumulated kids were of sundry sizes. Brown could tell immediately what the Indians intended to do.

Brown pleaded with the Indians, two of whom were apparently fairly old, to take his life but spare the children. In response, the warriors shot him and took his scalp. They then clubbed and scalped the rest of the children in attendance.

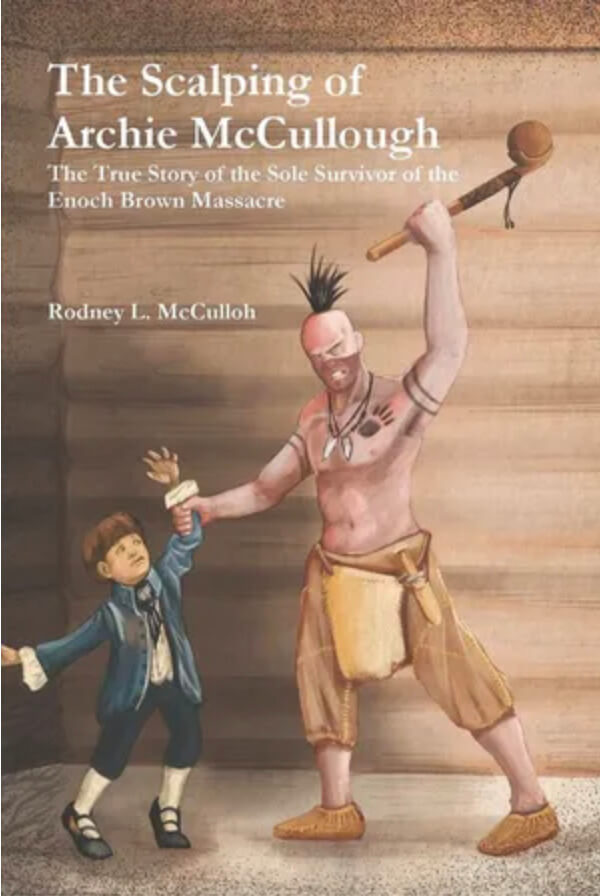

Time has muddled the details somewhat. I found two major narratives. The most common had ten of eleven children perishing in the attack. The eleventh, a young man named Archie McCullough, apparently lost consciousness and came to after the Indians had departed. He purportedly climbed into the fireplace until he was certain the Indians were gone and then made his way to a nearby stream to clean his wounds. He was found there by locals who investigated further and discovered the horror in the schoolhouse. Period reports claimed that the schoolmaster Mr. Brown died with a Bible in one hand trying to protect his charges.

The Rest of the Story

Brown and the ten children were buried in a communal grave. The site was not well marked, and locals feared that its location would be lost. In 1843 the area was excavated and the bodies were discovered. There were indeed ten children and one adult all buried together. There is a granite monument and a well-maintained park commemorating the site today. The names Ruth Hale, Eben Taylor, George Dustan, and Archie McCullough have survived, though the rest of the kids’ names have been lost.

Miraculously, little Archie survived the horrific attack. He recovered physically but was justifiably never quite right afterward. He purportedly married and had a son and daughter. Archie eventually settled in Kentucky, but his trail goes cold in 1810.

A man named John McCullough had been captured by the Delaware Indians and held captive in their camp since 1756. He was apparently a cousin to young Archie McCullough. The elder McCullough was present when the war party returned from their gory foray.

After he was released, McCullough wrote this of their reception, “I saw the Indians when they returned home with the scalps; some of the old Indians were very much displeased at them for killing so many children, especially Neep-paugh’-whese, or Night Walker, an old chief, or half king,—he ascribed it to cowardice, which was the greatest affront he could offer them.”

The Backlash

As you might imagine, when news got around that the Delaware Indians had murdered ten children and a schoolmaster in cold blood, the locals wanted some payback. With the approval of Governor John Penn, the Pennsylvania General Assembly reinstituted the scalp bounty that had previously been in effect during the French and Indian War. This offered $134 for the scalp of any adult male Indian above age ten and $50 for a female, payable by the government in cash.

There resulted a fairly unrestrained slaughter by enterprising capitalists who were handy with a gun and adroit at holding a grudge. The entire Conestoga Tribe was wiped out in the aftermath. The pastoral nature of Enoch Brown Park lends no overt insights into the horrors that took place there some 258 years ago.

Of all of Satan’s many diabolical inspirations, I think school shootings might be the worst. That someone might feel somehow justified in taking the lives of innocent children in response to some political insult, social inadequacy, or warped sense of justice simply astounds me.

However, make no mistake, there is nothing new under the sun. People are bad. We always have been. That’s the reason those incredible old guys penned the Second Amendment in there right behind the First.

.gif)