There’s a reason why most people shoot a .22 better than a .44 Magnum. Recoil has long been the enemy of realizing the full measure of a gun’s mechanical accuracy. At my range, I’ve seen many very strong and hardy young men talk up hard-kicking handguns like the Desert Eagle and the S&W 500. I’ve also watched many of those strong, hardy young men flinch magnum rounds into the dirt.

To paraphrase George Bernard Shaw, youth is wasted on the young. Now that I’ve shot long enough to shut off my inner reptile brain, my hands are admittedly achier than they once were. (Note: being a writer has not helped this condition.) As such, I certainly find myself in the ranks of those who see the worth of a “soft shooting” handgun.

You might find yourself with a similar value system for reasons of your own. If so, you’ll likely ponder the following: What makes one handgun shoot more stoutly or softly than another? This is an answerable question and one that transcends discussions of caliber alone.

Size And Weight

It’s been a while since many of us took high school physics, but we might dimly remember that force is equal to mass times acceleration. Many of us tend to focus on “force.” We can think of this as the power of the cartridge for which any particular firearm is chambered. However, we should be equally concerned with acceleration, and by that, I mean how rapidly any given gun accelerates into your hand under recoil. Newton’s second law tells us that acceleration and mass are inversely related for any given force.

Put more simply, big guns kick less than small guns of the same caliber. This seems counter-intuitive at first: Witness the number of well-meaning husbands who buy snub-nosed revolvers for their wives. Small guns seem cute, genteel, and easy to handle. That said, show me a lady who shot a scandium J-Frame .38 as her first gun, and I’ll show you a lady who had a horrible first trip to the range — and likely never returned.

If you want to keep recoil to a minimum, extra mass is the ticket. It’s another reason why I tend to prefer barrels of 6″ on revolvers and 5″ on autoloaders: More sight radius is nice, sure, but the extra weight out at the front of the gun adds just a little “special sauce” when it comes to taming recoil.

Ergonomics

A deceptive category, to be sure! Many people buy a revolver or semi-auto because it feels “good in the hand.” That’s better than nothing, but one also wants to make sure it feels good under recoil. The platonic ideal is a gun that fits one’s hand just so, with no gaps or recesses. This will allow the firearm and hand to behave as one unit under recoil, distributing all forces evenly. When this isn’t the case, it can feel like the gun is slamming back into one’s palm.

Sometimes our own biology is at fault when it comes to amplifying the negative effects of recoil. Many big-handed dudes have been cut by the slides of Walther PPKs and bit by the beak-like hammer of a Browning Hi-Power. Even a gun with a modest “kick” can be quite painful under recoil if your hand doesn’t interface with it well.

Personally, I don’t play well with medium- and large-framed guns from a certain manufacturer. Thanks largely due to their rectangular grip frame, they tend to vector recoil right into the knuckle at the base of my thumb — no thanks, I say. Not every pistol will work for every user, as we may perceive the effects of recoil differently from one another.

Grip And Grip Material

Wooden grips on a revolver can be a thing of beauty. However, there’s a reason why Ruger ships its Super Redhawks with big, cushy rubber stocks: Metal and wooden grips have absolutely no “give.” On a heavy kicking gun, hard grips won’t make things worse, but they certainly won’t make things better. Instead, rubber grips once again help to distribute recoil over a larger part of the hand and over a longer duration of time. Those gray-pebbled rubber Hogue grips might not be someone’s first choice of shoes for a vintage S&W, but aesthetics be damned — they work.

Another interesting variable comes in the form of polymer construction. Almost as a rule, polymer frames will be lighter than those made from aluminum or steel. Based on our previous discussion of weight, one would think this would indicate they’d be harder kickers. And yet, I’ve shot some polymer guns that shoot as softly as their metal-framed brethren.

I think the phenomenon comes down once again to “flex” or “give.” Some polymer compounds can act as shock absorbers, as they can be compressed or deformed more easily than metal but will rebound to their original, molded shape. The effect is slight but not negligible!

Additionally, how one grips the gun is important. A strong grip locks the firearm into place and again aids the goal of allowing the gun, wrist, hand and arm to move as one unit. (And, as a combined mass, will therefore accelerate less under the same recoil force.) But supposing one has a weak and/or improper grip, the gun will squirm in hand and distribute recoil forces unequally. Good technique will absolutely reduce the perception of recoil.

Action And Slide Velocity

Remember our previous discussion of a force being exerted over time? Well, it also applies here, and not all guns are created equal. While exceptions exist to the rule, most autoloaders can be classified into “blowback” and “locked breech” designs.

Blowback actions are the simpler of the two. When a round is fired in a gun of this design, only the stiffness of the recoil spring and mass of the slide inhibit its rearward movement until the chamber reaches safe pressures. As the gun cycles, the slide (and only the slide) moves backward, usually at a high velocity, contributing to a “snappy” feel when it rams into the rear of the frame. Usually, this action is reserved for guns chambered in smaller calibers.

Conversely, just about any gun chambered in 9mm or larger is going to have some kind of locking mechanism. If you watch a video of a 1911 or Walther P38 in extreme slow motion, you’ll see the barrel and slide travel together for a bit before the barrel unlocks and the slide continues its rearward movement. Recoil forces act on more things, in more directions and over a longer period of time. Recoil is generally felt more like a shove than a snap.

Guns chambered for .380 ACP — of which there are a lot — can be one of the two action types. My GLOCK 42, a locked breech design, is very comfortable to shoot. My Colt 1908 is far less pleasant, thanks to its blowback action. I’d also be remiss if I didn’t note there are blowback guns in larger calibers.

Additionally, springs are a factor. For example, H&K’s USP series of handguns utilize a dual spring system, where the last bit of slide travel under recoil is further dampened by a second, stiffer recoil spring. As I understand it, H&K moved away from this design in the name of simplification — why use two parts when one will do? I see the logic, but I (and other devotees) simply love how the USP setup feels.

Also, when guns have no springs or slides, there’s little to attenuate the recoil. A single-shot handgun or revolver typically has greater recoil than an autoloader of identical size, weight and caliber.

And Egads … More?

We haven’t even begun to touch on the effect of muzzle brakes, bullet weights and velocities, slow-burning vs. fast-burning powders, torque, weight changes as magazines deplete, aftermarket parts and add-ons and the much-ballyhooed subject of bore-over-frame height. And I’m sure there are even some factors I’m forgetting.

The main takeaway is there are so many different variables and so many guns we’re rarely able to make apples-to-apples comparisons when it comes to recoil. Sure, I can tell you a 4″ gun will kick more than a 6″ gun if it’s the same make, model and caliber. Or an M&P .40 will kick more than an M&P in 9mm. However, if you were to ask me off the top of my head whether a Ruger LCR in .327 Federal kicks more than a .45 ACP-chambered 1911 stoked with +P+ ammo … who knows?

Don’t get me wrong: Keeping track of all of the above variables is certainly helpful when it comes to identifying soft shooters or hard kickers. However, the real world almost always complicates our well-crafted theories. Sometimes you just have to shoot a gun to find out how much you can tolerate the kick, push, shove, or slap it transmits when you pull the trigger.

One night while taking call for our busy medical practice I got a most extraordinary inquiry. A woman called the clinic after-hours line to report an unusual medical emergency. She reported that somebody had crept into her home and cursed her with testicles.

I pondered her quandary for a moment, imagining the medical article I could get out of that patient presentation. A grown women sprouting a set of testicles should be good for the cover of “The Lancet” at the very least. Alas, I simply questioned whether or not she had been taking her psych meds regularly and discovered a much more plausible explanation for her problem. However, that did spark an interesting train of thought.

Testicles are indeed a curse. American women live, on average, a full five years longer than men. 93.2% of the incarcerated population in America is male. If that doesn’t sound like a curse, I fail to fathom what might.

The deleterious effects of testosterone toxicity have been vigorously explored in this very venue. I would assert, however, that the dark influences of this most potent poison take hold at a shockingly young age. In the case of the young man we will discuss momentarily, it began at a most sensitive time.

Potty training is a difficult period in any kid’s life. One day you’re tearing about peeing anytime and on anything as the spirit leads, and the next your parents are imploring you to apply a certain unnatural discipline to this most natural of functions. That process can go smoothly or not so much.

Our hero was a little tow-headed nit, the kind of scamp whose very presence brings a smile. The only time he sat still was when he was unconscious. Some of his sustenance was derived via food he shoved down his gullet, while the rest he seemed to absorb through his face. This young man was simply adorable.

His parents were making great strides in the potty training process. The kid was eager to please, and his folks made it a game. No matter what he was doing, when the urge hit he scampered into the bathroom, threw up the lid, and did his business.

The kid had to step up on his tiptoes to accommodate the geometry of Mr. Crapper’s masterpiece (No kidding, the guy who perfected the flush toilet was an Englishman named Thomas Crapper. One of his nine patents covered a contraption called the Floating Ballcock. Google it.) Thusly configured, his little miniature manhood was just barely up to the task.

The kid’s mom had adorned the toilet seat lid with one of those covers made from thick shag carpet that were popular back in the day. I have no idea why people ever gravitated towards those things. It made the commode look like some enormous turquoise space fungus. Those thick covers also had some unfortunate effects on the physics of the device.

One day the young man was busily attempting to destroy the entire world when the urge struck. He duly dropped whatever it was he was breaking and made a beeline for the water closet. In one practiced motion he threw up the lid and threw down his pants. He strained up on his toes to get his plumbing properly arranged and let fly. However, in his haste he had approached the throne from a quartering angle.

As luck would have it the fluffy toilet seat cover kept the lid from quite reaching its position of rest past dead center. Occupied as he was with his urinary marksmanship the poor kid failed to notice the offending toilet seat as it gradually crept back his direction. With shocking ferocity the combination seat and lid slammed back down. Alas, fate is a foul mistress. One of the two plastic feet on the bottom of the seat described an arc straight down onto the poor kid’s diminutive manhood.

Much of human learning is the result of basic Pavlovian conditioning. Positive experiences draw us closer, while the negative sort tend to push us away. It was this time-rested process that ultimately put robots on Mars. In this sordid circumstance this inopportune geometry set back toilet training some months. Having a heavy toilet seat smack his little penis like a hammer was adequate to precipitate an insensate dread of all things bathroom-related. I lost track of the family soon thereafter, but the poor guy might yet insist on just going in the backyard to this very day.

Made in association with Rizzini, the EJ Churchill Hercules is a true all-rounder, as comfortable on a game drive as it is at the local clay ground, says Michael Yardley

This month we look at two EJ Churchill Hercules guns. The guns, a 12-bore and a 20-bore, are over-and-unders made in association with Battista Rizzini in northern Italy but benefit from EJ Churchill’s gunmaking, game-shooting and instructional experience.

EJ CHURCHILL HERCULES REVIEW

Both guns are sideplated and profusely engraved with acanthus scrollwork in Churchill’s attractive house style (applied by laser but finished by an artisan). The 12-bore EJ Churchill Hercules, as primarily tested, has a coin-finished action, whereas the 20-bore Hercules Colour has a chemically applied case-hardened effect to the action. The latter version of the gun costs significantly more but also has enhanced wood (both guns have a traditional English oil finish).

The guns featured have 30in barrels, which would be my call in this type of gun in 12- or 20-bore, although as a bespoke product there are other choices from 28in to 32in. They weighed in at 7lb 10oz and 7lb 2oz, respectively, with open-radius full-pistol-grip stocks. The grips themselves are well-proportioned and steel-capped. The stocks present with elegant tapered combs and sensible shelf dimensions. They are, however, usually ordered to the customer’s measurements. There are all sorts of no-cost stock options available on the Hercules, including straight hand (which may be had with double triggers), palm swell and half pistol grip, and a Monte Carlo comb.

This model, launched in March 2020 (five days into the Covid crisis), is also available in 16-bore, 28-bore and .410, all with fixed or multi-chokes. I have to express a prejudice in favour of the 30in 20-bore. It is a combination that rarely fails to please, although the 12-bore has arguably more versatility and the 28-bore will bring a smile to most faces, as will the .410 if you have the skill to use it.

The test guns both had automatic top strap conventional thumbpiece sliding safeties (a non-selective safety is another no-cost option). They are fleur-de-lys proofed for steel shot and each has an excellent solid, tapered (8mm to 6mm) sighting rib, solid joining rib and rounded game fore-end without schnabel, so those who want to extend a front hand may do so without the hindrance of a lip.

The Hercules is intended as an all-rounder. It would be ideal in a traditional line or hide, on a simulated day or simply in a casual session breaking pitch discs with friends at the local shooting ground. EJ Churchill has now sold well over 100 of this model and says: “It is our best-selling gun and for a good reason. This gun was designed for the modern game shooter who demands a sharp-shooting game gun that is as happy in the field as it is on the clay ground.”

Unlike others, these guns will shoot game or clays equally well. The weights and shapes are right and conform to my own ideals. There is enough mass to steady the guns and absorb recoil but not so much as to make them ungainly or ponderous in use. They feel comfortable and the aesthetics are good.

I have a particular fondness for sideplate guns of this type. The plates provide extra space for decoration but also put a little more weight between the hands, so they handle more like sidelocks while benefiting from the reliability of a CNCmade trigger-plate action. This design has evolved considerably over the past 40 years due to British market preferences and English gunmaking input pushing it on. It is a much better-looking and better-made gun than it once was. It’s particularly good in 20-bore with a solid rib. The action aesthetics and handling have progressed but the basic mechanical design always was sound and reliable.

TECHNICAL

The EJ Churchill Hercules is precision-built on a proven trigger-plate design used by several Brescian makers and further refined with English input. It combines elements of Beretta and Browning. Trunnion hinging by means of stud pins at the knuckle contributes to the lowering action profile, reducing muzzle climb/flip and improving action aesthetics into the bargain. Rearwards the gun is locked by means of a Browning-style flat bolt engaging a slot bite beneath the bottom mouth. Some makers prefer the Boss/Perazzi system at the rear to reduce action height where a bolt comes down upon elliptical projections that locate in recesses in the lower action face. Beretta does it with its clever conical bolts either side of the top chamber mount. Rizzini has continued with the simple Browning-style bolt but paid significant attention to refining action shapes, notably by rounding the bottom of the action bar. The design is simple, elegant and reliable.

SHOOTING IMPRESSIONS

I shot the 12-bore Hercules at EJ Churchill’s Buckinghamshire ground. It was the sort of gun that makes testing a pleasure from a shooting point of view but tough journalistically. The Hercules didn’t miss a beat; the evolved specification is spot on. The stock shapes were also excellent. In use, the 12-bore did not recoil excessively, the trigger-pulls were fine and the gun looked good – it would not disgrace itself in any company. Pleasing, too, is the engraving and there is no excessive bling. I did not shoot the 20-bore as pictured but I have shot a nearly identical gun with great results. The combination of a 20-bore action with 30in barrels and solid rib works especially well. I would struggle to criticise these guns. The Colour version is a little more expensive but looks superb. The Hercules is on the money.

KEY INFORMATION FOR EJ CHURCHILL HERCULES

♦ RRP: 12-bore Hercules, £11,500; 20-bore Hercules Colour, £14,000

♦ EJ Churchill, Park Lane, Lane End, Stokenchurch, High Wycombe HP14 3NS

♦ 01494 883227

James Woodward & Sons are considered by many as building the best guns of all time.

James Woodward started out in the trade apprenticed to Charles Moore around 1827. James Woodward worked his way through the ranks to become the head finisher at Charles Moore. They later became partners c.1844 and the firm moved to new premises at 64 St James’s St, Pall Mall, trading as Moore & Woodward.

“Woodward’s had build an excellent reputation for best guns mostly being sold to the aristocracy.

At some stage Moore dropped out of the business c1851 and James Woodward later became James Woodward & Sons c1872 when James took his two sons James and Charles into partnership at the same address. James the son of the founder ran the business until his death on the 7th July 1900, his brother Charles had already died some five years earlier. The firm was then taken over by the nephew of James, Charles L Woodward. Records show that the firm later moved address in 1937 to 29 Bury St, but then suffered bomb damage in the Second World War and were temporarily accommodated by Grant & Lang at no 7 Bury St, untill no 29 was put back in order..

Woodwards had build an excellent reputation for best guns mostly being sold to the aristocracy, you needed to have deep pockets to be on the order books. Now if you can find a good clean example a side by side will fetch just under £10.000 but the over and under is around the £20.000 mark. These guns are not common and you will have a job to find a good one. There was one story being told by the leading London berrel-filer c1930 that Woodwards would reject any barrels that he had regulated for them unless he was able to get as few as two or three extra pellets into the standard pattern ! Perhaps this is why Woodwards with their original choke boring throw perfect patterns.

It has been said that guns made by James Woodward & Sons have been consistently the best guns ever seen. Better than Purdey, H&H and Boss, but this I guess is down to one’s own taste. The Company concentrated on Shotguns and especially their legendary sidelock side by side game gun with its arcaded fences and signature T Safty. 29 inch barrels were a standard for Woodward as this was seen to be most efficient but other sizes could be ordered. The Prince of Wales stock was also a favourite of Woodward. We also encounter from time to time single triggers and sidelever’s but these were not the standard unless ordered otherwise. Although Woodward had their own single trigger design.

The firm was most well know for its development and production of its over and under design in 1913 by Charles L Woodward. This and the Boss over and under were and still are without doubt the two best designs ever produced, and again its personal preference to which is considered better. In 1948 Charles L Woodward wanted to retire and offered the business to Tom Purdey who acquired it as a going concern.

Once Purdey had acquired James Woodward & Sons they immediately adopted the Woodward over and under design in favour of their own and it is still being made today.

The firm of James Woodward & Sons certainly deserves merit for their contribution to the over & under gun of today. And for those lucky enough to own one of their Classic game guns or the famous over and under, you have a rare treasure indeed !

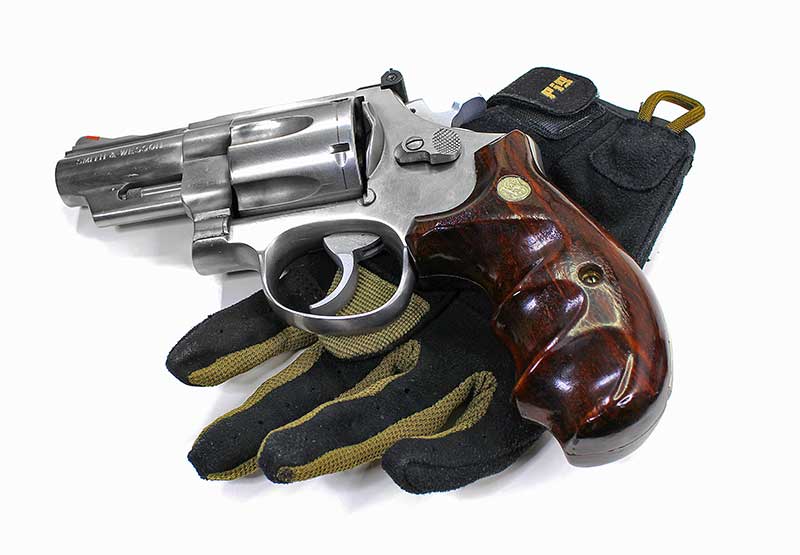

During my high school years as I started reading the likes of Elmer Keith and then a little later Bob Hagel and John Lachuk I also acquired a deep interest and then even deeper affection for the .44 Special. In the mid-1960s Charter Arms brought out the first .44 Special Bulldog. It could not have come at a better time.

The .44 Magnum arrived in very late 1955 and started showing up in gun shops in 1956. There were many who foolishly felt the .44 Special was dead. Elmer Keith retired his, Skeeter Skelton traded his 4″ 1950 Target .44 Special in on a Smith & Wesson .44 Magnum with the same barrel length, and by the mid-1960s, both Colt and Smith & Wesson had dropped the .44 Special from their catalogs. The only way one could have a .44 Special was to find a used one, convert something like a .44-40 Colt Single Action to a .44 Special by fitting a new cylinder, or buy a Charter Arms Bulldog.

Charter Arms managed to keep the meagerly flickering flame of the Special alive, at least until Skeeter realized his mistake and admitted the 4″ .44 Magnum was too much of a good thing and traded it off, replacing it with another 4″ Smith & Wesson .44 Special. During the ensuing years, S&W’s attention to the .44 Special was sporadic at best. It wasn’t until our own Mike Venturino, Clint Smith and Editor Roy twisted arms at S&W (with the cooperation of Tony Miele there) a few years ago, a fixed-sight, N-Frame .44 Special became a catalog item for S&W once again.

All during this time, except for a brief closed doors session, Charter Arms continued to offer .44 Specials. As this is written .44 Special sixguns are available from Colt, Freedom Arms, Ruger, Smith & Wesson and Taurus. However, Charter Arms is currently the only manufacturer offering a small-frame, 5-shot, double-action .44 Special, with adjustable sights.

That First One

The original Charter Arms .44 Special in the 1960s was a blued, 5-shooter with a 3″ barrel. At the time it was one of my most-carried sixguns and logged many miles in the top of my boot. One year, now more than 30 years ago, we rented a motorhome and took a rare vacation with the kids, who were all in high school at the time — and the .44 Bulldog was stashed in the camper and it came in handy. Twice in my life a gun protected my young family, and in both cases the gun I had with me was the .44 Bulldog.

Sometime after introducing the original blued .44 Special Bulldog, Charter Arms came out with what they called a Target Model. It was an excellent idea, poorly executed. Somehow, someone thought they could come up with an adjustable-sighted .44 Special Bulldog by putting a shroud over a relatively thin barrel. Perhaps it could happen, however there has to be some way to anchor the shroud just as Dan Wesson did with the locking nut on the end of their barrels. Instead Charter Arms tried to hold the shroud on with one screw at the bottom of the shroud in front of the frame. It did not work well.

Modern Models

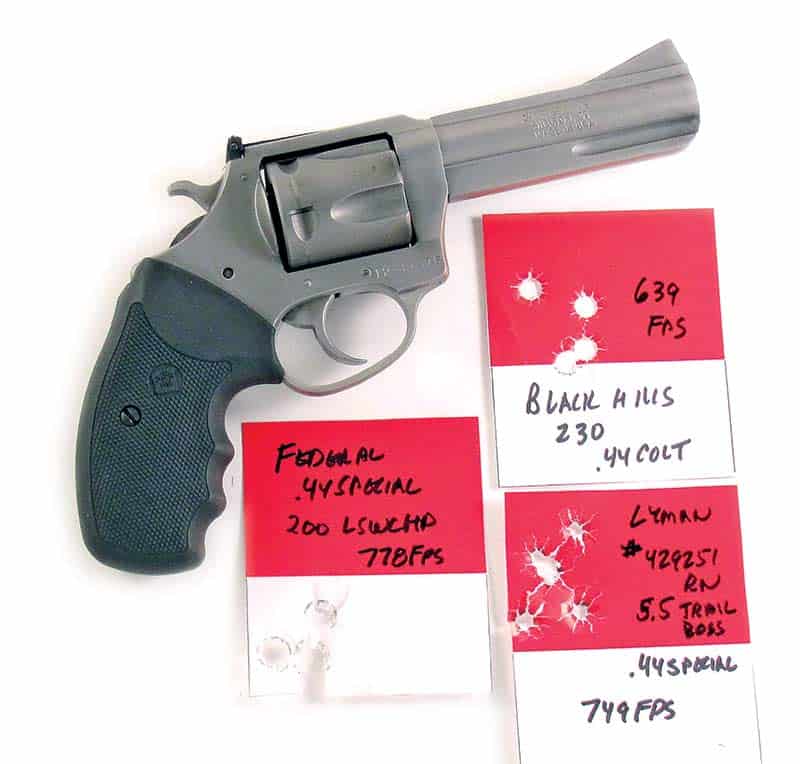

Today’s Target Bulldogs bear little resemblance to the original idea. The barrel is not shrouded but rather is a full under-lugged barrel properly screwed into the frame. Both 4″ and 5″ versions are available, complete with an adjustable rear sight and a ramp front sight. For my eyes, loads and hand, the front sight on both .44 Special Bulldogs was too tall, requiring the rear sight to be adjusted up too high to the point I feared I would lose the adjusting screw. The simple solution for me was to take metal off the top of the front sight.

The 5″ .44 Special Target Bulldog we tested worked perfectly and smoothly from the beginning, both double and single action. However the 4″ version had a little hitch in the trigger when fired double action and Tom, my gunsmith at Buckhorn, smoothed this out for me and reshaped the front sight.

Let’s take a closer look at the Target Bulldogs, which are basically identical except one has a 1″ longer barrel. Weights are approximately 20 and 22 ounces for the 4″ and 5″ Bulldogs, and that extra 2 ounces and 1″ longer barrel makes quite a difference in feel or balance or whatever we choose to call it. The shorter barrel seeming to nestle back in the hand while the longer barrel seems more muzzle heavy. These are both all stainless steel, except for the black adjustable rear sight assembly, 5-shot, double-action, very easy packing, weather-beating, go along anywhere revolvers.

Barrels are full under-lugged, rounded off at the bottom front for easy holstering, having an attractive scalloped cut-out running the length of the underlug in front of the cylinder ejector rod. It’s quite attractive and also removes a very slight amount of weight. The trigger is smooth while the hammer is serrated for easy single-action cocking. Both are also quite easy to operate double action.

The top of the frame is flattened with the rear sight assembly very nicely fitting inside the rear sight channel with no part of the assembly protruding above the frame. Grips are full wraparound, finger-grooved, checkered rubber which will not win any prizes as far as looks are concerned, however function-wise they are just about perfect for these little .44s.

With their 5-shot cylinders allowing the bolt cut to be placed between rather than directly under the chamber, Charter Arms .44 Special Bulldogs have always been stronger than any loads I would normally wish to use in them. They are certainly not .44 Magnums, but will handle .44 Specials and.44 Russian and .44 Colt rounds.

The latter two, designed for Cowboy Action Shooters, are quite pleasant to shoot and actually could be quite effective with their 200–230-grain bullets at nearly 700 fps from the longer barreled Bulldog, and 650 fps from the 4″ .44 Special.

The 5″ Bulldog was test-fired at 20 yards with the .44 Russian loads from both Black Hills and UltraMax grouping in 11/8″. With the shorter barrel I shot at a more realistic self-defense distance of seven yards, with the Black Hills 230-grain .44 Colt load grouping in 3/4″. So these loads not only shoot easily they are more than adequately accurate.

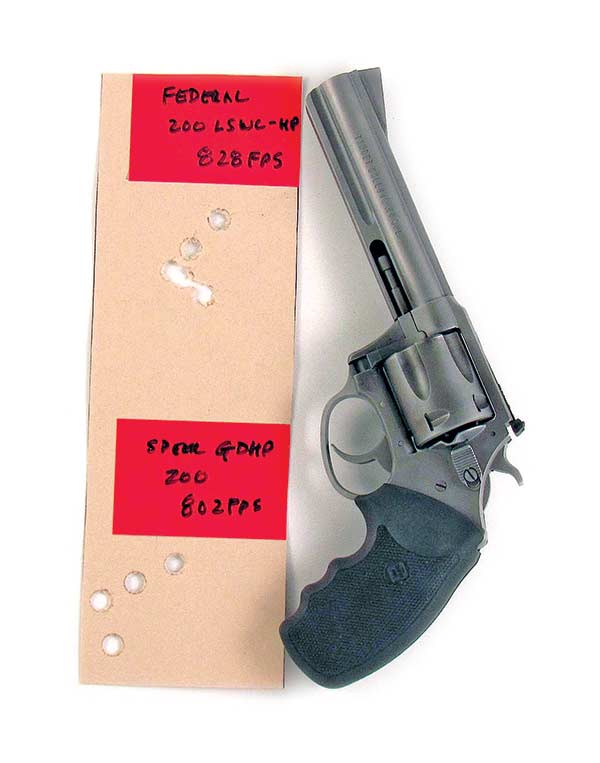

Defensive Loads

Switching to more serious .44 Special hollowpoint loads saw the Federal 200-grain lead SWC-HP clock out at 825 fps, with a 20-yard group of 7/8″ from the longer Bulldog and 775 fps and 3/4″ at seven yards from its smaller brother. Winchester’s 200-grain Silvertip JHPs do 766 fps and 11/4″ from the 5″ Special. For those wanting a heavier bullet, the Winchester 240-grain lead flatpoint does well over 700 fps.

My most-used .44 Special load consisting of the RCBS #44-250 Keith bullet over 7.5 grains of Unique clocks out at over 1,000 fps in the 5″ Bulldog which is quite a bit of energy coming from the barrel of such a small sixgun. The original .44 Special load from over 100 years ago can be duplicated with the Lyman round-nosed #429251 bullet over 5.5 grains of Trail Boss. This load does 750 fps and delivers 1″ groups from the 4″ Bulldog.

Both Speer and Hornady offer self-defense loads for the .44 Special, with the latter Critical Defense version a 165-grain JHP with a muzzle velocity over 1,000 fps, while the Speer 200 Gold Dot is at 800 fps and designed to expand at .44 Special velocities. Either one should be a good choice.

Keepers

I definitely like both of these stainless steel Bulldogs and they will not be going back. These little Charter Arms revolvers will find duty outdoors or in vehicle carry. Bulldogs definitely have a serious application, however sometimes we just need plain and simple fun shooting.

With these Bulldogs I can see this means .44 Russian and .44 Colt loads used for big-bore plinking along with the duplicated original .44 Special roundnosed load. There was a time in my life I felt everything had to be loaded full bore. Thankfully those days are passed and I can also shoot for enjoyment. Getting smarter is one of the few benefits of getting older.