Military history of Liberia is often covered only in the context of the civil wars fought between 1990 – 1997 and 1999 – 2003. Before those tragic conflicts, Liberia had an odd and unique army, mirroring the unusual story of the nation as a whole.

(US Army soldiers in Liberia during WWII. They are armed with M1903 Springfields and a M1917, both of which would be used by the Liberian army after WWII.)

(Liberian soldiers loading M1 Garands during the 1980 coup.)

(A modified M1917A1 guarding a roadblock near Monrovia during 1992.)

(A guerilla loyal to the warlord Charles Taylor during the 1990s, armed with a WWII Soviet PPS-43. Child soldiers were used by Taylor in outrageous numbers; at points more than half his force was under the international military age of 17.)

Liberia during WWII

Liberia has an unusual origin. Starting in 1822, four decades before the USA’s civil war, emancipated slaves in the USA were encouraged to emigrate to Africa. Liberia was one of the settlements; as was the Maryland Republic and Mississippi-in-Africa; both later annexed by Liberia. Liberia declared independence in 1847.

The settlers, who called themselves “Americos”, never were more than a tenth of Liberia’s population and later even less. They were concentrated in cities along the Atlantic coastline. Despite this they dominated the political, economic, and military life of the country; at the expense of tribal groups of the inland interior, the “hinterland”.

(From 1847 – 1980 Liberia was a one-party democracy of the True Whig party. The True Whigs maintained traditions of the pre-1860s American south, including tailcoats and top hats, into the 1970s. Here a True Whig official reviews a Liberian army unit with WWII-surplus M1 pot helmets, M1/M2 carbines, and M1936 web belts. The reviewing officer is armed with a M1911.)

In the capital Monrovia and other coastal cities, there were similarities to American culture. Many of Liberia’s symbols mimic American ones.

(USS Palau (CVE-122) flying the Liberian flag at the courtesy position on the mainmast during a 1947 visit to Monrovia. USS Palau was launched on 6 August 1945, the same day as the Hiroshima mission, but commissioned after WWII was already over. USS Palau decommissioned in 1954 and was scrapped.)

As seen above, Liberia’s flag is very similar to the USA’s; but only has one large star.

Even though Liberia indirectly came out of the United States, the USA did not even recognize it diplomatically until 1862. There was little American interest in its affairs until the 1920s and significant military aid did not start until WWII.

Liberia’s army was originally called the Liberian Frontier Force, or LFF. It policed Liberia’s inland borders against incursions by European nations. Its secondary roles were to quell periodic rebellions by tribes in the hinterland, and to enforce tax law there.

(One of the LFF’s earliest weapons was four hundred Mauser Kar. 88 carbines bought from Germany, which Liberia called the M1888. These were presumably gone by WWII.)

(The Liberian Frontier Force name lived on long after the frontiers had been finalized. Here the colors are being dipped to visiting Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands in 1958.)

(During 1918 Liberia bought one hundred M1898 Krag rifles surplused by the American military, along with a quarter-million rounds of .30-40 ammunition.)

(LFF troops in the late 1930s, just prior to WWII. They are still armed with the old Krags.)

The LFF officer corps was entirely of the coastal Americo elite. It was theoretically possible for infantrymen of hinterland tribes to move up the NCO ranks and perhaps even gain a commission, but before and during WWII this was extremely rare. From 1912 onwards, the US Army dispatched officers to assist in running the LFF, which before WWII numbered only 1,000 troops; all foot infantry in one regiment.

(FN M24(L) of the Liberian Frontier Force.) (photo via Mauser Military Rifles of the World book)

Above is what might be considered the LFF’s first contemporary 20th century gun, the bolt-action FN Model 24 short rifle, in Liberian form usually called FN M24(L) to differentiate it from the WWII Haitian army’s FN M24(H) which was nearly identical. Liberia bought these guns from Belgium during the 1930s. In look, function, and form they are similar to the German 98k or Czechoslovak vz.24 rifles of WWII.

(Liberian soldier still with a FN M24(L) during the 1950s. Compared to the M1903 Springfield, the Mauser can be identified by the washer in the buttstock, the “knuckle” at the lower base of the stock’s hilt which the Springfield lacks, and the longer length of barrel between the forward end of the furniture and the muzzle.)

This was the LFF’s standard longarm during WWII and beyond. The date which the FN M24(L)s finally left service is unknown. As American military aid picked up during the Cold War era, there was little need to retain them alongside the Springfields and Garands.

WWII in Europe began in 1939. Liberia declared itself neutral but this did not stop the far-away war from affecting the nation. German u-boats hunted Allied merchant ships trading with Liberia. During 1941 U-103 sank the freighter S.S. Radames as it was leaving Monrovia. A year later, U-68 sank the tanker M/T Litiopa near Robertsport, and then the merchants S.S. Fort de Vaux and S.S. Baron Newlands only 40,000yds from the Liberian shoreline.

Because of the Firestone plantation (described later below) and other business interests, the United States began paying military attention to Liberia even before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. During 1940, a visit by the cruiser USS Omaha (CL-4) laid the framework for future cooperation.

After the USA entered WWII, American forces were stationed in Liberia. The American military deepened Monrovia’s harbor, built the Robertsfield facility described later below, and trained the LFF.

(Military infrastructure construction during WWII.)

(A Boeing 314 of Pan-American Airlines being refueled in Liberia during WWII. PanAm clippers supported the American war effort in both the European and Pacific theatres, flying contracted routes for the War Department.)

(Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Edwin Barclay in a Willys MB during FDR’s state visit to Liberia in 1943.) (Library Of Congress photo)

Despite abandoning neutrality and allowing American forces to be based on its territory, Liberia did not declare war on Germany and Japan until January 1944. The LFF offered to send units to Europe but this was not taken up. Liberia was eligible for Lend-Lease but did not receive much in the way of weapons. Lend-Lease records show that the LFF was provided six training rifles and 1,000rds of .22LR, plus four shotguns and 500 12ga shells. The specific type of guns was not recorded. One single Harley-Davidson WLA military motorcycle was provided. Most of the Lend-Lease aid was non-lethal to help Liberia’s wartime economy, including 500 tons of rice.

WWII ended in September 1945. American forces were withdrawn in February 1946.

the Firestone plantation and Robertsfield

These two things, one predating WWII and the other built during the war, would have lasting effects on Liberia.

(The location of Robertsfield to the town of Harbel and the plantation.) (map via PBS)

During the first two decades of the 20th century, rubber became an important industrial commodity worldwide. There is nowhere in the United States amenable to rubber trees, which was both a headache for the automotive industry and a national security concern.

During the early 1920s the Firestone company explored options for a rubber plantation abroad. The Philippines, then an American commonwealth, was rejected as it would have high shipping costs and an uncertain political future. A test plot in Mexico failed. Another option showed more promise: Liberia. It had the perfect climate and soil, was English-speaking, and on ocean trade routes.

In 1926 Firestone signed a 99-year lease with Liberia for 1,000,000 acres (1,562 miles² or about the size of Luxembourg in Europe or Rhode Island in the USA) at 6¢ per acre annually.

(House 53 was the quarters of the plantation’s general manager. During the 1990s the warlord Charles Taylor briefly used it as the “white house” of his self-styled “Greater Liberia Republic”.) (photo via PBS)

(M1 towed 40mm AA guns after receiving tires at the Firestone factory in Akron, OH during WWII. It is highly likely that the rubber of these tires originated in Liberia.)

Whatever its labor rights issues, the plantation did serve its purpose during WWII. By mid-1942 the only major rubber sources still in Allied hands were Ceylon (today Sri Lanka) and the Belgian Congo (today the D.R. Congo). During WWII Firestone and the US Army cooperated to build a hydroelectric dam that powered not only the plantation, but also the town of Harbel to the immediate south. As of 2022 the WWII hydroelectric facility is still in service.

(LCT(6)-623 off Normandy.) (photo via navsource website)

During WWII, the US Navy’s nameless LCT(6)-623, a Mk6 landing craft, put men ashore at Normandy in 1944.

(M/V St. Paul, the former WWII landing craft serving the Firestone plantation.)

After WWII it was discarded as surplus by the US Navy and bought by Farrel Line. Extensively altered by Bethlehem Steel during 1948, it was renamed M/V St. Paul and ferried liquid rubber latex for the Firestone plantation. The former landing craft could venture 15 miles inland up the Farmington river but was still seaworthy enough to sail along Liberia’s Atlantic coastline to any Liberian port.

South of Harbel, which was more or less a “company town” associated with the plantation, was Robertsfield. It was built by the US Army during WWII as Roberts Army Airfield, named after Joseph J. Roberts, Liberia’s first president.

(Vickers Wellington of the South African Air Force at Robertsfield during WWII.)

(B-26 Marauders at Robertsfield during WWII.)

By the time WWII ended, Robertsfield was a major asset. After the US Army departed in 1946, a spinoff of PanAm was hired by the Liberian government to operate it as Roberts International Airport. It is often associated with the capital Monrovia, 15 miles west. The capital actually has its own airport (Spriggs Payne), but due to the size of Robertsfield it became Monrovia’s de facto air hub.

(A “Connie” of PanAm at Robertsfield in 1949, four years after WWII. In the foreground is a demilitarized B-17 Flying Fortress.)

(“Civilianized” B-17s were not as popular as one might imagine after WWII. There was a lot of red tape to get FAA approval and the bomber was simply not designed as an economical transport. None the less, some were demilitarized. An evangelical group used this Flying Fortress in western Africa, including Liberia, from 1949 – 1951.) (photo via Assemblies Of God)

Although now in civilian Liberian control, Robertsfield remained important to the American military. Robertsfield had two runways, one of them being over two miles long.

(The prototype Concorde at Robertsfield in 1976. Behind it is a RAF C-130 Hercules on layover.)

A runway like this was rare in Africa. The US Air Force used it as a refueling point for Strategic Air Command bombers. During the 1980s, Robertsfield was one of the Space Shuttle’s designated emergency landing sites.

After WWII the presence of the Firestone plantation and Robertsfield lulled the True Whig elite and Liberian military into a false sense of security. In actuality, by 1980 Firestone was already cutting back at the plantation as synthetic rubber became cheaper, while the American military was using Robertsfield less and less. The USA once again cared little about who was running Liberia.

WWII weapons in the Liberian military

American military aid to Liberia began only a few months after American troops departed in 1946. An American detachment known as LIBMISH supervised the distribution of military aid after 1959. WWII-surplus weapons came to Liberia through three programs.

(A US Army general listens to a speech at the BTC, or Barclay Training Center, in Monrovia during the 1960s.)

EDA, or Excess Defense Articles, gives allies surplus gear “as-is, where-is”. In 1974 Congress mandated that unless a waiver is granted, the value of EDA has to be returned by the military to the US Treasury. Presumably this was to prevent transfer of “excess” gear that wasn’t really excess. Liberia, formerly a prime user of EDA for WWII-era equipment, saw its transfers fall by two-thirds in 1975.

FMS, or Foreign Military Sales, is a program where the United States provides low-interest loans to the recipient for them to buy American weapons. These can be either new or used. FMS loans to Liberia were suspended in 1984; previously they had sourced a lot of WWII-era guns.

MAP, or Military Aid Program, transferred surplus WWII (and later, modern) weapons through a process where recipient countries were issued free “credits” that they could then request American weapons against. The country had to illustrate a need for the item and the ability to use it; and could be blocked by Congress. Depending on what it was, the items were usually “billed” at a fraction of their WWII cost, sometimes $0.

Liberia was frankly under no military threat for the first 20 years after WWII. Liberia’s three neighbors were still colonies of WWII allies: Guinea and Ivory Coast became independent from France only in 1958, and Sierra Leone from the UK not until 1961. As such, the army was not a huge priority and the LFF existed in a sort of “sleepy, dreamy” status, not modernizing much other than WWII-surplus gear from the USA.

In 1962 there was a realization that Liberia was falling behind. The military was restructured into the Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL). The former Frontier Force became the National Guard and the former tiny Coast Guard, the AFL Navy Division. Little else was done and the WWII weapons continued in use.

(Demilitarized C-47 Skytrain in 1966. Liberian National Airways, later Air Liberia, ceased operations in 1990.)

There was no air force. Even though the USA had huge numbers of entry-level types (combat-capable T-6 Texan trainers, etc) being surplused at low cost, there was apparently no money for warplanes, no interest in them, or both.

(The yacht Virginia prior to being bought by Liberia.)

The same went for the tiny navy. It numbered around 200 – 300 men, almost all of the Kru tribe. Despite the glut of smallcraft, patrol boats, and service ships being disposed of by the post-WWII US Navy, there was little interest in warships.

The ship pictured was the 189′ yacht Virginia, built in the UK during 1930 for the 1st Viscount Camrose, William E. Berry. Liberia bought Virginia from the Viscount’s estate in 1957, three years after his passing. Renamed Liberian, it was by far the largest “naval” vessel and was used as a presidential yacht. No actual warships were acquired until two little cutters were donated by the US Coast Guard in the late 1950s.

During 1971 then-president William Tolbert Jr sold Liberian as a public relations effort to dampen criticism of waste and corruption. It caught fire in Sierra Leone later that year and was wrecked.

Liberia likewise missed out on things like WWII tanks, half-tracks, heavy artillery, etc being discarded by the USA after WWII. As the 1960s began, Liberia’s military was still mostly a foot infantry force.

the M1903 Springfield

The M1903 was the US Army’s standard service rifle during the first world war, and saw limited use during the second. Springfields served throughout WWII and there were many still in government inventory after WWII.

The M1903 was a quality rifle of the bolt-action era. Measuring 3’7″ long and weighing 8¾ lbs, it fired the .30-06 Springfield cartridge (2,800fps muzzle velocity) from a stripper-loaded five-round internal magazine. Overall it was reliable, accurate, and durable.

No M1903s were Lend-Leased to Liberia during WWII. However they were already in inventory soon afterwards. One possibility is the USA’s Foreign Liquidation Commission, which was established two months after WWII ended to lessen American war gear marooned abroad when WWII ended. This commission had authority to sell minor or obsolete equipment within whatever region it happened to be when Japan had surrendered. M1903s equipped the US Army garrison in Liberia during WWII, and some may have been sold in lieu of shipping them home.

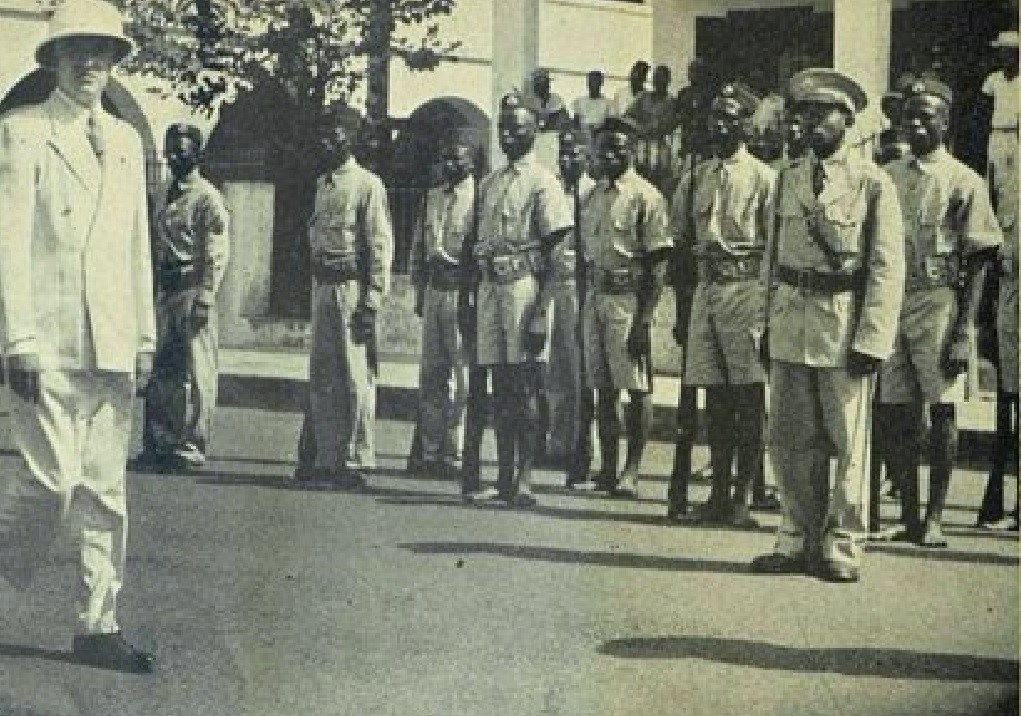

(This late-1940s photo shows M1903s already in the LFF; identifiable by the straight angle to the buttstock’s underside; lacking the “knuckle” of either the M1 Garand or the pre-WWII Belgian Mausers.)

The American dignitary reviewing the troops above is Edward Stettinius Jr who had been Secretary of State during WWII. The purpose of this 1947 visit was to establish his private second career, the Liberia Company and Stettinius-Associates Liberia Inc. The former was a road-building venture. The second, and more lucrative company, invented the “flag of convenience” concept in shipping, where freighters fly the flag of a nation not their own to gain tax advantages. After Stettinius passed away in 1949 it was renamed International Registries Inc. and was highly successful. IRI moved to the Marshall Islands during the 1990s after the warlord Charles Taylor kept shaking it down for more and more money.

M1903s were an item eligible for EDA transfer during and after the Korean War and more probably came during that time, by that route.

(M1903 Springfields being carried by Liberian soldiers during a 1956 parade.)

(M1903 Springfields during the mid-1960s. M1 Garands are interspersed, as the Liberian military considered them equal weapons.)

By 1970 the era of bolt-action rifles was clearly long since past, and Liberia’s M1903s were passed to secondary units or scrapped.

(A Liberian MP at Belle Yellah still with a M1903 Springfield in 1970. Belle Yellah had originally been the very first LFF base during the 19th century. The barracks were barbed-wired in and converted into Liberia’s most notorious prison.)

No M1903s were observed during the 1990s carnage, where they would have been completely outclassed by AK-47s.

the M1 Garand

(photo via National Rifle Association)

The semi-automatic M1 Garand was the USA’s standard battle rifle for all of WWII, all of the Korean War, and beyond. It was a highly-effective firearm, perhaps the best of WWII.

The M1 Garand was 3’7½” long and weighed 9½ lbs. It fired the .30-06 Springfield cartridge from an internal 8-round en bloc.

(President Barclay inspecting an en bloc during a visit to Ft. Belvoir, VA during WWII. Despite the demonstration of the M1, Liberia was ineligible to receive Garands via Lend-Lease during WWII.)

After a small test lot in 1962, Liberia began receiving M1 Garands in bulk during 1963. Via MAP, 1,508 Garands were delivered that year. Between 1964 – 1967 another 465 came for a total of 1,973 via MAP by the beginning of 1968. All were drawn out of US Army European Command holdings.

(LFF soldier with M1 Garand in 1962. These men belonged to the Presidential Guard unit in Monrovia, and were the first to receive Garands.)

(Liberian soldiers with M1 Garands during the mid-1960s.)

Besides the MAP transfers, Liberia bought another 3,000 M1 Garands through FMS between 1968 – 1974. When procurement ended in the mid-1970s, the AFL had 4,973 M1 Garands which was almost the same as the entire number of men on active duty.

(AFL soldiers with M1 Garands march in Monrovia during 1971.)

(The Presidential Guard unit with M1 Garands in 1973.)

(Liberian soldier with M1 Garand in 1980.)

(Liberian soldier with M1 Garand during the early 1980s.)

replacement

The semi-automatic M1 Garand was a step up from the bolt-action M1903 Springfield. None the less by the 1960s the newly-acquired WWII semi-autos would themselves soon be outclassed. During the mid-1960s Liberia made a buy of FN FALs from Belgium. Not enough were obtained to replace the M1 Garand entirely.

(In name anyways, tattered remnants of the AFL fought on during the early 1990s. This photo was taken in 1992 and shows a FN FAL fighting Charles Taylor’s forces.)

By the 1980s the M1 Garand was overdue for retirement yet many remained in service. Liberia made a private buy from Colt of 1,100 M16s. The M16s and FN FALs combined perhaps could have sufficed yet M1 Garands continued on in dwindling use throughout the decade.

the M1/M2 carbine

(photo via Royal Tiger Imports)

Unrelated to the M1 Garand rifle, the M1 carbine of WWII was a “light rifle” intended for roles not necessarily requiring a Garand but something more than a handgun. It was 3′ long and weighed just 6 lbs.

The semi-automatic M1 fired the .30 Carbine (1,990fps muzzle velocity) from either a 15- or 30-round detachable magazine.

Introduced during the last eleven months of WWII, the M2 was a version with select-fire (full auto) capability.

Liberia received its first M1 carbine as part of the very last 1945 Lend-Lease package. One single M1 (booked at “total value transferred $46” in American records) was delivered, along with 1,000rds of ammo. Why only a single gun was Lend-Leased has been lost to time.

MAP transfers started in 1951 and ran sporadically in small batches until 1965. Liberia received 62 M1s and 24 M2s via MAP. Another 100 M1/M2 carbines (no breakdown was made) came via EDA. In all, Liberia received 187 M1/M2s.

(A 1977 photo showing a M1/M2 carbine in a Liberian honor guard. The occasion was the visit of Ivory Coast’s president. The AFL 4th Infantry Regiment inherited the unit flag of the Liberian Frontier Force after the military was restructured in 1962.)

Plainfield M2s

During 1978 a company called Fargo International brokered a buy of ten Plainfield M2s to Liberia’s paramilitary national police.

(photo via m1carbinesinc website)

These guns had a strange story. In 1960, a company called Millville Ordnance Company, or MOCO, in New Jersey was one of several companies in the USA rebuilding WWII M1/M2s from parts off already in the USA and “re-imports”, guns brought back from post-WWII military aid recipients with their receivers torched to comply with federal law. MOCO did not have the necessary tooling and skills to make new receivers and barrels, and contracted Plainfield Machine to make them.

As Plainfield was doing this, unbeknownst to them, the CEO of MOCO was convicted of exporting unlicensed weapons to the Caribbean. With him in jail, Plainfield was left sitting on invoices that MOCO could now not pay, and the guns.

(1962 advertisement from Shotgun News magazine.)

Plainfield offered them for civilian sale and then made more for the South Vietnamese army, in several modifications. The version sold to Liberia was called the PM-30G and was a select-fire M2 differing from the WWII baseline in having a deluxe walnut stock and a perforated guard atop the barrel.

What happened to these ten guns after the 1980 coup is unknown.

replacement

During the late 1970s Liberia bought Uzis from Israel. These had the advantage of using 9mm Parabellum which was much easier to obtain worldwide by then than .30 Carbine.

(Four guns of two generations: from left to right a M1/M2 carbine, a M16, a M1 Garand, and an Uzi; in Monrovia during the 1980 coup.)

M1/M2 carbines were in limited use during the 1980s but were not seen during the civil war period. Presumably by then, it would have been extremely hard to source .30 Carbine ammo on the black market.

the M1918 BAR

The Browning Automatic Rifle concept originated during the first world war, as a “walking fire gun”, a fully-automatic weapon of rifle size firing rifle-caliber ammunition; to accompany infantry with bolt-action rifles during an advance.

By WWII several concepts: the submachine gun, the general-purpose light machine gun, and the high loss rate of infantry making an open charge; had made that redundant. None the less the M1918 was successful during WWII. One or two automatic rifleman were included in a standard infantry squad. The BAR was useful in providing accurate bursts of automatic fire. M1918s were used throughout all of WWII and the Korean War.

The BAR was 4′ long and weighed 19 lbs. It fired the .30-06 Springfield cartridge at 600rpm from a 20-round detachable magazine.

Liberia obtained 57 M1918A2s via MAP during the 1960s. Surprisingly some were still in use during the 1990s civil wars.

(One of Charles Taylor’s fighters with a captured BAR in front of the burned PanAm terminal at Robertsfield during July 1990. The bipod is missing.) (photo by Patrick Robert)

replacement

Select-fire rifles like the M16 made the whole BAR concept obsolete, as now every soldier was in theory an automatic rifleman. None the less, the AFL liked this concept and during the 1980s, it replaced BARs in frontline units with Model 611s bought directly from Colt, the so-called “heavy barrel M16”.

the M1917A1

This machine gun served the United States during both world wars and the Korean War. The M1917A1 was actually Liberia’s first machine gun type, less one single M1895 potato-digger bought from the USA during the 1930s.

The M1917A1 fired the .30-06 Springfield cartridge from 250rds fabric belts at 600rpm. All-in (gun, tripod, water chest, and one ammo box) it weighed 103 lbs.

By the 1990s, when this gun was still in Liberian service, liquid-cooled infantry machine guns had been relegated to history. The disadvantages of liquid cooling were the physical size and weight. The WWII advantage was that air-cooled machine guns had to be fired in bursts, less the barrel overheat. With liquid cooling a gunner could fire at will. During a demonstration of the second prototype M1917, it fired for 48 minutes 12 seconds. It could have continued but the test was halted as it had already churned through 21,000+ rounds.

The cooling jacket held 7 pints of water and was enclosed by oiled asbestos packings. Inside at the top was a tube-in-a-tube, the outer one slightly shorter and sliding over the inner one, which had a hole on top at each end. If the barrel heated enough to boil water, steam rose to the top of the jacket. Elevating or depressing the gun used gravity to slide the outer tube to cover one or the other holes of the inner tube, so liquid water could not swamp it but steam would be forced into it. Steam exited a portal near the muzzle via a hose that led to the M1 water chest. The other end of the hose was kept beneath the waterline in the chest, where it condensed back into liquid. If too much water boiled away, water from the chest was quickly poured into a fill portal and firing resumed.

How many M1917A1s Liberia received, and when, is not clear. None were included in Lend-Lease during WWII and there is no MAP record of any being transferred. It is possible they were obtained through EDA. Alternatively it is not beyond belief that Liberia bought some completely outside of the American systems from private arms dealers after WWII. The 1988 edition of Small Arms Today lists this WWII weapon as still in Liberian service at that time, but without the usual clarification as to how many or from where.

The above photo from 1992 shows a M1917A1 at an AFL roadblock near Monrovia. It is perplexing for a number of reasons, the least being that a M1917A1 was still in combat during the 1990s. Beyond that, there is some kind of counter-lever device fitted astride the action. This was not milspec and may have been an ad hoc field modification for anti-aircraft use decades previous, in that the gunner could lean on the armpieces instead of supporting the gun’s weight in one hand with the wood pistol grip, which is still installed. Whatever the device is, it precluded mounting the ammo box on its bracket. During WWII the US Army advised against leaving it on the ground as the weight of the belt stressed the receiver. The tripod is not milspec, it has part of the WWII M2 tripod but new legs. Finally the rear sight, water chest, and hose are missing; not surprising as this was almost half a century after WWII. The soldier in the cap is pointing at the water filling portal.

Above is a close-up of the same M1917A1. Some sort of carrying handle is strap-banded to the jacket behind the front sight. The steam discharge portal can be seen; looking head-on it is at the 5 o’clock position; at the 7 o’clock position on the other side would be a dummy hole for the plug to screw into when the gun was in use. As mentioned the hose and M1 water chest are missing. Contrary to what is sometimes claimed; the gun will not rupture from steam pressure if the chest is not used, however steam would hiss out the portal and leave a telltale puff at the gun’s position. If the M1917A1 was fired totally dry, it would quickly overheat.

The three men are Nigerian soldiers of the ECOMOG force. By this time ECOMOG had abandoned its initial mindset of impartial peacekeepers and was allied with the remnant AFL against the warlord Charles Taylor.

replacement

During the 1980s Liberia bought some MG 710-3 light machine guns directly from SIG in Switzerland. The country was slated to receive a small number of M60s as aid from the United States; but it is unclear if they were ever delivered. At least one M1917A1 still soldiered on, as seen above.

how it all ended

By 1979 the Americos were less than 1⁄20 of Liberia’s population. Shortly after midnight on 12 April 1980, a 29 year-old half-illiterate master sergeant from the hinterland, Samuel K. Doe, gathered sixteen other junior soldiers and scaled the wall of the presidential mansion. They executed President William Tolbert asleep in his bed. With that, 133 years of unequal True Whig rule came to an end and the nation’s most severe problems began.

(MSgt Samuel Doe in 1980.)

In post-WWII Africa coups were not uncommon. As many power changes happened by coup as by elections. What shocked other African strongmen was that there was a “code” to coups: usually some senior general would plot, amass forces and weapons, secretly ally with other generals and wealthy business interests, and only then attempt a coup. It was unheard of for a junior enlistedman to do it on a whim.

(Liberian soldier with a WWII American M1911 shortly after the 1980 coup. Liberia received these sidearms via military aid from the USA and they served alongside Smith & Wesson revolvers and MAC-10 auto-pistols bought commercially.)

Doe’s coup was (at first) very popular with the AFL and the population as a whole, who were tired of the True Whigs and the two-tiered society. Doe consolidated power by arresting Tolbert’s cabinet. They were given a sham trial, tied to telephone poles on the Monrovia beachfront, and shot.

(An executioner loads an en bloc into his M1 Garand. The thirteen executions were filmed but too graphic for here. Despite being just 10 yards away, some of the shots only wounded the targets and multiple volleys were needed. This was petty barbarism compared to what Liberia would endure in the next 23 years.)

A quirk of the executions was that one of the doomed politicians was the son-in-law of Félix Houphouët-Boigny, Ivory Coast’s dictator. In the unwritten African coup “code”, family of foreign leaders was a faux pas and this trivial detail would haunt Doe a decade later.

Doe’s popularity evaporated fast. A member of the hinterland Krahn tribe, his cabinet was drawn from the Krahn, and any important government job or military leadership was Krahn. In turn, he had a grudge against other hinterland tribes and made them scapegoats from the many problems which arose from his misrule during the 1980s.

last days of WWII weaponry in the AFL

Doe was many things: a drinker, under-educated, and a kleptocrat. He was also strongly anti-communist in his speeches. The USA used this as proof of his Cold War credentials and aid continued to the tune of $52 million over ten years, much of it embezzled.

In reality it is unlikely Doe even fully understood what capitalism and marxism were. Doe had a strong admiration for the USA’s president, Ronald Reagan, and just reiterated Reagan’s 1980s philosophies.

In October 1986, Doe received an invitation to a military event in Clinceni, Romania; a Warsaw Pact member. These generic invites are often sent by militaries to foreign leaders, with no expectation of them actually coming. For whatever reason, Doe decided to attend and met Romania’s communist dictator, Nicolae Ceausescu. Despite being polar opposites, the Reagan-acolyte Doe and arch-marxist Ceausescu struck up an friendship and signed a $5 million weapons deal which astonished both the KGB and CIA.

The main part of the package was PM md.63/65 assault rifles; Romania’s clone of the AKM. This was the first introduction of Kalishnikovs into Liberia. By the turn of the millennium AKs of various types would blanket the country. Other combloc kit was RPG-7s, ZPU-4 anti-aircraft guns, and BTR-50 and TAB-77 APCs.

(One of Charles Taylor’s teenage soldiers with a PM md.63/65. Taylor’s forces captured many, adding them to their holdings of other AK variants from elsewhere.) (Associated Press photo)

Now with the Romanian assault rifles serving alongside the American-made M16s and Belgian FN FALs, there was little remaining role for the M1 Garands of WWII and their withdrawal was hastened during the late 1980s.

WWII weapons in the first civil war

Charles Taylor had originally been a Doe supporter until fleeing to the USA in 1983. Unlike Doe, Taylor was university educated, an articulate speaker, and highly intelligent. He was also unbelievably brutal and harsh; a borderline psychopath.

In 1984, upon request of the Liberian government, Charles Taylor was arrested in the USA.

(Charles Taylor’s mugshot.)

What happened about a year later was another bizarre story. On 15 September 1985, Taylor escaped from a jail in Plymouth, MA. Years later, Taylor’s 1990s fighters said he either used folk magic to charm the Americans, or sawed through the bars. During 2009 Taylor himself said that late that night in 1985, a stranger had opened his cell, led him into the minimum security area, and told him that if he jumped the fence a getaway car would be waiting. He did, and a car indeed was. Taylor said that he felt the men driving the car in 1985 were CIA agents. No explanation of the jailbreak has ever been provided by authorities in Massachusetts. Maybe they were CIA, maybe not. Five inmates escaped the jail that night; the other four were recaptured.

Taylor was driven to NYC where he blended into the Liberian diaspora. He made it to Mexico, and from there flew to Libya. Muammar Quadaffi provided Taylor with guerilla warfare training and encouraged him to find a “jumping off point” to overthrow Doe.

From Libya, Taylor flew to Burkina Faso which was not thrilled with his ambitions and then bounced around the region, Ivory Coast, Senegal, Guinea, and back to Burkina Faso; looking for a “jumping off point”.

(Taylor’s personal weapon was a customized AK-47 with underfolding stock and an American M203.) (photo via The Star newspaper)

Now his luck picked up. Blaise Compaorè had taken over Burkina Faso via coup. Under Compaorè, Burkina Faso was allies with Ivory Coast, where Houphouët-Boigny still held a grudge over his son-in-law’s fate in 1980. With this, Taylor now had an entry point into Liberia’s northeast hinterland.

On Christmas Eve 1989, Taylor led fewer than 200 ill-equipped men across the Ivorian/Liberian border and easily overran a demoralized AFL unit, getting more weapons. This started a snowball effect.

If any army on Earth in 1990 was ill-prepared for war, it was Liberia’s. The AFL had no tanks, no helicopters, no radars, almost no artillery, and few APCs. Morale was horrendous due to Doe harassing non-Krahn tribes in the hinterland. The army had four “standard”-issue rifles (M1 Garand, FN FAL, M16, and PM md.63/65) each using different calibers. Equipment ranged in age from WWII to 1980s.

During early 1990 Taylor’s force, the NPFL, racked up win after win. Few AFL units fought hard and some outright defected. Taylor gained new recruits from non-Krahn civilians in the hinterland. The only setback was when one of his lieutenants, Prince Johnson, deserted to start a splinter force which also aimed to overthrow Doe.

(The warlord Prince Johnson.)

As Liberia collapsed, a Nigerian-led peacekeeping force called ECOMOG was formed to facilitate a cease-fire before the war reached densely populated Monrovia.

(Ghanian soldiers of ECOMOG in Monrovia during 1990. One is wearing a WWII British Mk.II Tommy helmet. The machine gun is a MG3, the post-WWII version of the MG-42 chambered for 7.62 NATO.)

ECOMOG’s mandate slowly changed from impartiality to keeping Taylor out of the capital at all costs.

Samuel Doe’s end came on 9 September 1990, not by Taylor but by Johnson. That morning, Doe travelled across Monrovia to meet Ghanian and Gambian officers of ECOMOG. Supposedly one item on the agenda was to be a scolding from Doe, as he felt a Nigerian ECOMOG general had acted too casual in his presence.

By still-unknown ways, Prince Johnson learned of the meeting. Johnson threw most of his forces into a “flying column” of technicals (Toyota pickups with machine guns) that burst through an ECOMOG roadblock and barrelled into Monrovia. Doe was captured and executed.

Johnson was briefly “president” of Liberia, with his rule limited to Monrovia and the suburbs. His government fell apart and between late 1990 – 1992, the only recognized authority in Liberia was ECOMOG. Meanwhile, Charles Taylor controlled the vast majority of the country, which he called the “Greater Liberia Republic”, also ecompassing diamond-bearing areas of Sierra Leone. Taylor’s unrecognized “republic” included Robertsfield and the Firestone plantation.

During this period (1990 – 1993) the last “new” WWII gun entered Liberia, and it was a surprising one.

the PPS-43

The PPS-43 was a simpler counterpart to the USSR’s famous PPSh-41 submachine gun of WWII. Like that gun, it used the 7.62x25mm Tokarev cartridge (1,640fps muzzle velocity). It weighed 6½ lbs and was 2′ long with the 8″ stamped metal stock folded in.

Along with the UK’s Sten, the PPS-43 was one of the crudest guns of WWII. Almost the whole thing is stamped steel. The PPS-43 was full-auto only at 550rpm cyclical, from a 35-round banana magazine.

Externally the most interesting feature is the muzzle. A piece of stamped steel curved into a ⊂ shape directs some escaping gasses sideways and backwards, like a crude muzzle brake. Internally, the buffering “system” is simply a piece of leather (photo below) which the bolt slams into. This had to be changed periodically; about the only upkeep a PPS-43 needed.

(photo via Apex Gun Parts)

In theory this submachine gun was accurate to 200 meters (218yds); in practice anything further than 90yds was as much luck as marksmanship. The purpose of this gun was to be made as fast as possible, in the biggest numbers possible. Between 1 – 2 million were made during WWII. PPS-43s were made so fast (including inside Leningrad during the seige) that the Soviets themselves did not know exactly how many.

After WWII trying to pinpoint who in Africa got PPS-43s when is often a fool’s errand. The Soviets seeded them around the continent between the 1950s – 1970s: Libya in the north, Guinea-Bissau in the west, Congo-Brazzaville in the center, Angola and Rhodesia in the south, up to Somalia in the east. Many crossed borders to new users, some multiple times.

(One of Charles Taylor’s soldiers with a PPS-43 during 1990.) (photo by Patrick Robert)

For Liberia, there are two possibilities.

The more likely account is that in 1990, as Charles Taylor’s army ballooned in size and needed weapons, Libya routed PPS-43s through Burkina Faso which were then sent into Liberia.

A less likely possibility is that some were already in Liberia, having been added as a “sweetner” by Romania to the Doe-era arms deal.

(Taken at Robertsfield during June 1990, this photo shows soldiers who said they were loyal to Samuel Doe’s AFL. One is armed with a PPS-43; the others modern M16s or PM md.63/65s. During the summer of 1990 loyalties were sometimes opaque and fluid.) (photo by Jacques Langevin)

Arms dealers were active in Liberia, including Guus Kouwenhoven and Viktor Bout. The latter is probably more famous. Bout established a front company, Abidjan Freight, to handle the Liberia / Sierra Leone markets for his operation, San Air. The San Air planes were re-registered under a fictional airline name, West Africa Air Services.

(After Bout’s 2008 arrest, his four-engined Il-76 was abandoned at Umm al-Quwain Free Trade Airport near Sharjah, U.A.E. The plane was falling apart by the 2020s and was scrapped in 2022.) (Associated Press photo)

Viktor Bout obtained an Il-76 “Candid” from the defunct Soviet air force in the early 1990s. Originially registered to the U.A.E., it was reregistered to Liberia until many nations started airspace bans against Liberian airliners. It was then reregistered to Switzerland until Swiss authorities caught wind of what Bout was doing, then the Central African Republic, then the U.A.E. again, and finally the Russian Federation.

(Bout also used a twin-engined An-8 “Camp” formerly of the Russian airline Aeroflot. In the window of the unmarked An-8 was taped its Liberian airworthiness document. This was likely fake; by the mid-1990s Monrovia only had sporadic electricity and running water; it’s doubtful anybody was doing foriegn airplane certifications by then.) (photo by Jan Kopper)

Bout’s planes flew all over buying and selling: Somalia to Afghanistan, to the Russian Federation and “The Stans” (former Soviet SSRs in Asia), to eastern Europe, to Burkina Faso and Liberia. Deliveries to Taylor were usually made at Robertsfield, or in a neighboring country with the guns and ammo travelling overland.

(The PanAm terminal at Robertsfield in 1997, seven years after its destruction. The two long runways remained intact throughout the civil wars, able to receive planes as big as an Il-76. PanAm itself went bankrupt in 1991. It had abandoned Liberia as an unprofitable route even before that.)

Payment was tendered by Taylor through accounts of Oriental Timber Company, an old True Whig-era corporation, or in raw diamonds which were then fenced in Antwerp or New York City. Additional revenue came from usurping the Firestone plantation’s rent which was then re-routed to banks serving arms dealers.

There were two flights in 1994 and 1995 originating in Albania where cargo included “Soviet submachine gun ammuntion”. This was almsot certainly 7.62 Tokarev for the PPS-43s.

(A man loyal to the warlord Charles Taylor training on WWII PPS-43s during the 1990s. Two magazines were usually “jungle-styled” with duct tape as above.)

For certain, the PPS-43 was only an “add-on” to Taylor’s arsenal; almost all of his men used AKs or FN FALs with the Kalishnikov platform slowly becoming the standard type. None the less, the PPS-43s were not museum pieces or toys. Most engagements of the first civil war saw 50yds or less separating combatants and a WWII submachine gun was equally lethal to a modern assault rifle in such settings.

(One of Taylor’s underage soldiers with a PPS-43. Charles Taylor recruited entire underage battalions, which he called SBUs (Small Boys Units). They were often paid in ganja (marijuana) in lieu of cash and told to loot any food or clothing they needed. Taylor also introduced crack into SBUs, a narcotic previously unknown in Liberia.)

(PPS-43 in action alongside a AK-47 during the mid-1990s. Looting was one of every other imaginable atrocity including cannibalism. Even behind the front lines, civilians were at constant risk of being robbed. Poor people with nothing to loot were sometimes shot out of frustration.) (Associated Press photo)

From the period 1993 – 1997, the first civil war became something of a stalemate with ECOMOG controlling Monrovia and some pockets along the coast, and Taylor’s “Greater Liberia” being the rest of the nation. This was the swan song of WWII weapons in Liberia. The remaining American-origin weapons, which had to be few by then, were unprofitable for arms dealers to keep supplied with .30-06 Springfield. As for the PPS-43s, they were gradually drowned out by the flood of Kalishnikovs coming into Liberia.

(This 1992 photo shows a unit of the remnant AFL still with a M1 Garand in use alongside M16s.) (photo by Patrick Robert)

(A fighter of Charles Taylor’s NPFL during 1996, armed with a WWII PPS-43.) (Associated Press photo)

(A M1918 BAR amazingly still in service in 1996. It has all of its WWII accruments: the bipod, carrying handle, and GI sling.)

postscript

The first civil war ended in 1997 with Charles Taylor becoming president of Liberia. The second civil war, 1999 – 2003, ended with Taylor going into exile (he was later jailed as a war criminal) and civilian rule restarting in Liberia. No WWII weapons were used during the second conflict.

In 2005 the United States reconstituted a new AFL. As there were already so many AK-47s in the nation, it was selected as the standard service rifle. All of the WWII equipment was by then just a memory. However the new Liberian Defense Department insignia has a USMC Ka-Bar and a M1 Garand, two WWII items which had served the first AFL.