As the light turned to dark, a male leopard cautiously followed a well-worn path in the shadow of Mount Kilimanjaro. The cat had been here before, perhaps as recently as the previous night. As he slipped in and out of the long grass, the leopard passed the dimly glowing lights from a nearby manyatta (village), then continued on his seemingly purposeful mission, stopping frequently to sniff tracks and check out his surroundings with his superb nighttime vision.

Native voices, possibly herdsmen, faded away as the leopard crept along, now closer to the ground. It stopped and crouched even lower, peering through the grass to watch the comings and goings of people in a tented camp. The big cat waited patiently until the strange voices were silent. Then, beneath a bright, cold Africa moon it started to sneak toward the camp.

The leopard approached one tent and circled it silently before its attention was drawn to another. Still creeping low and undeterred by the flickering light of the campfires, it picked up its pace and, with the brazen audacity common only to leopards, it rushed through the open flap of the tent and in a flash, stole away with its chosen prey.

The year was 1903; the place was German East Africa (later Tanganyika, now Tanzania). The camp was that of two hunters: Kalman Kittenberger, a young Austro-Hungarian sporting gentleman, and an old African military man, a corporal at the Moshi Garrison.

The men, who had pitched their tents about 100 yards apart, had arrived to hunt elephants in the area, which was soon to be a protected reserve. Their tents were pitched adjacent to two separate trails that each hunter would scout separately the next day.

That night Kalman had visited the old African’s tent and had drank and talked well into the wee hours. The old African owned a bulldog named Simba, perhaps for its tenacity, but a strange choice of dog in this climate. The breed’s short nose and breathing passage makes it hard for the dogs to stay cool, and it would probably have had suffered much discomfort in the days to come. The bulldog is also prone to suffering from heatstroke. But the old African loved his dog and it went everywhere with him, usually sleeping under his bed. On this night, however, his loyal companion was snatched from beneath him with unbelievable speed by the marauding leopard.

The African wasted no time in grabbing his 7mm Mauser and firing at the fleeing cat. The commotion brought his colleague rushing from his tent and the two hunters fired in the general direction of the escaping leopard.

Everything was silent as the hunters followed the predator into the inky blackness. Unlike lions, leopards have a habit of doubling back and attacking their pursuers at incredible speed. Knowing this, the two men proceeded with extreme caution, their eyes gradually adjusting to the dark. Intermittent clouds obscured the moonlight, making their task even more difficult. Listening for the leopard’s distinctive cough or the dog to whimper, the two men moved silently through the long grass. The only sound was from their pounding hearts.

After a short time the hunters stumbled across the dog’s body. Their shots had apparently missed, but at least they forced the cat to drop poor Simba. Like a ghost, the leopard had escaped to live and maraud another day.

There were many stories of man-eaters prior to World War I in East Africa, but lions weren’t always to blame. Leopards were, in fact, the bigger culprits, and stories such as this were not uncommon. Cattle and other livestock were in particular danger, but unbeknownst to most Europeans at the time, leopards also accounted for many human injuries and deaths. But their favorite prey was the dog. They snatched them from camps and villages, sometimes in broad daylight right in front of their masters. One has to realize that leopards were far more common than lions; indeed, they could be found almost everywhere on the African continent, but because of their secretiveness, they were seldom seen.

The Guns of Avalon

Finnish-made Mosin Nagant M39s are considered by many experts to be the best of the type. Of them, those produced by Sako are arguably the best of the best.

Several years ago I reviewed a Valmet-made M39 here in “The Shootist.” It performed superbly, and I was rather sure I’d never find a Mosin Nagant I liked more.

Then I found the Sako version reported on here. It is without doubt the nicest Mosin Nagant I’ve had the pleasure of handling, at least in terms of build quality and retained condition.

Engineered by the Finnish Civil Guard and adopted by the Finnish Army on 14 April, 1939, the M39 is a much-improved derivative of the Russian-designed M1891.

Importantly, every M39 is built using an M91 action. According to Brent Snodgrass and Vic Thomas’s excellent article “The Claws Of The Lion: The Model 1939 Rifle,” “The bolt, magazine assembly and portions of the trigger were [also] retained….” However, the barrel, stock, and hardware, including sling connections, sights, nose cap, and so forth were all replaced.

Changes to the stock include the use of a pistol grip, a heavier profile in areas of the M91 prone to breakage, and the use of warp-resistant Arctic birch. Two different types of sling attachment points were incorporated and made the M39 equally suited to use by infantry or mounted troops.

Interestingly, earlier Finnish adaptions of the Mosin Nagant utilized a bore diameter of 0.3082 inch. To make the M39 compatible with captured Russian ammo, barrels were reamed to 0.310 inch. Twist rate was also changed, to 1 turn in 10 inches rather than 1:9.5.

Because wartime demand delayed retooling, M39 production was slow, and the first Sako-made M39s were fielded in the spring of 1941. One source suggests that Sako delivered about 66,500 M39s to the Finnish Army between 1941 and ’45 and about 10,500 to the Civil Guard. Total wartime production of M39s, from all makers, tallied 96,800 rifles.

Mechanicals

Operation of the Mosin Nagant is in general very familiar to shooters, so I won’t go into detail here. In short, the design features a rotating push-feed bolt with dual, opposing locking lugs; a single-stack, non-detachable magazine with an interrupter to prevent double-feeds; and a short, straight bolt handle.

The ladder-type rear sight is quite sophisticated, enabling fine adjustments to 800 meters and coarse “volley fire” elevation to 2,000 yards. As for the front sight, it’s stout and provides fine windage adjustment courtesy of dual side screws.

Provenance

Unlike many vintage war-surplus rifles, it’s no struggle to date this rifle. While there’s no telling when the original octagon receiver came out of Russia, the date the rebuilt rifle left Sako is plainly stamped: 1944. Judging by its condition, it never made it into combat. I found it while prowling the used-gun treasures in the Brownells retail shop. Because of its excellent condition, I didn’t haggle over the price. The cartouches, proof stamps, and other marks are all present, clean, and correct. I’d say this rifle was quite a find.

Rangetime

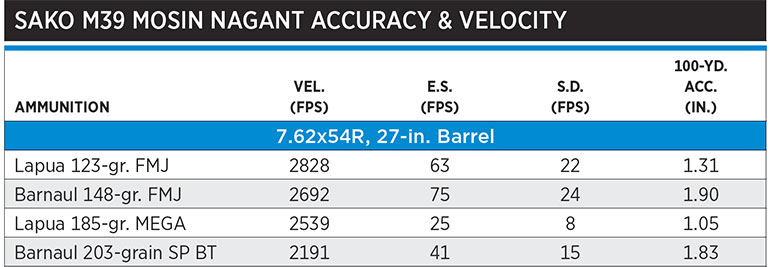

As much as I love the history and superb craftsmanship behind these Finnish battle rifles, like Col. Townsend Whelen I find accurate rifles to be the most interesting. My Valmet-made M39 is a real shooter, and I was intensely curious whether the Sako version would measure up. So I gathered a stack of noncorrosive 7.62x54R ammo made by Barnaul and Lapua and headed to the range. My eyes aren’t what they once were, so I pasted six-inch black Birchwood Casey bullseyes on big white backgrounds and sprayed the rifle’s iron sights with Birchwood Casey sight black to eliminate glare. Then, I bore down on the sandbags and did my best.

Since Finnish 7.62x54R ammo utilized a 200-grain projectile at about 700 meters per second (roughly 2,300 fps), which is slower than most of the Russian loads, most M39s hit high at 100 yards. The Sako is no exception. My first Lapua 185-grain MEGA bullet clocked over 2,500 fps and impacted about 9.5 inches high. Maintaining my six o’clock hold on the black bull, I fired again, then a third time.

To my astonishment, the three bullets made a cloverleaf that measured 0.48 inch, center to center. The next three-shot group measured 0.98 inch. Although hot barrels and full-length wood stocks with constrictive metal barrel bands don’t play well together, I fired a third group without allowing the barrel to cool because I was curious to know whether point of impact would shift and groups would open up.

My third group—with the barrel quite hot—measured 1.71 inches, indicating that either accuracy does indeed deteriorate as the barrel heats or my eyes were getting tired—or both.

Lest you think it was an anomaly, that 0.48-inch cluster wasn’t even the best group of the day. A bit later, Lapua’s 123-grain FMJ load posted a 0.35-inch three-shot group.

Both Barnaul loads I tested averaged just less than two MOA. One, a 203-grain softpoint load at about 2,200 fps, impacted precisely on point of aim.

Of the many Mosin Nagant rifles I’ve fired, my Sako is the easiest to shoot accurately.Finnish rifles are known for smooth, reliable function, and the Sako M39 is no exception. It fed and fired everything I ran through it comfortably and without hiccup.

Sako M39 Mosin Nagant

- Type: Bolt-action repeater

- Caliber: 7.62x54R

- Magazine Capacity: 5 rounds

- Barrel: 27 in.

- Overall Length: 46.75 in.

- Weight: 9.75 lbs.

- Stock: Arctic birch

- Finish: Blued barrel and action, oil-finished stock

- Length of Pull: 13.25 in.

- Sights: Ladder-type rear, windage-adjustable winged blade front

- Trigger: 5.3-lb. pull (as tested)

- Safety: Rotating cocking piece

- Manufacturer: Sako, sako.fi