Modern folks living in Jerusalem, Hiroshima, Bastogne, Volgograd, or Rome likely don’t believe anything of consequence ever happened in their neck of the woods. Familiarity might not necessarily breed contempt, but it does reliably foment apathy. It’s tough to get excited about the history of a place with which you feel you are so intimately familiar.

I admit to harboring a bit of that myself. I live in the suburbs of a tiny little town in north central Mississippi. My community is little more than a crossroads, so the suburbs reference is a subjective assessment at best. Suffice to say, I do like my solitude.

It was the pastoral aspect of the place that first sold me on it. My little corner of heaven is quiet. When it isn’t, I made it that way.

Then I bumped into a sweet lady in my medical clinic who had grown up hereabouts. She related a most fascinating local tale that reached all the way back to the American Civil War. Her story was poignant, gripping, disturbing, and sad all in comparable measure. It also unfolded underneath my very feet.

That brief discussion sparked a quest for the details. This deep into the Information Age, those details were readily ascertained. All that was required was a determined detective with a serviceable Internet connection. The lion’s share of what you are about to read took place within two miles of where I sit typing these words.

Table of contents

Total War

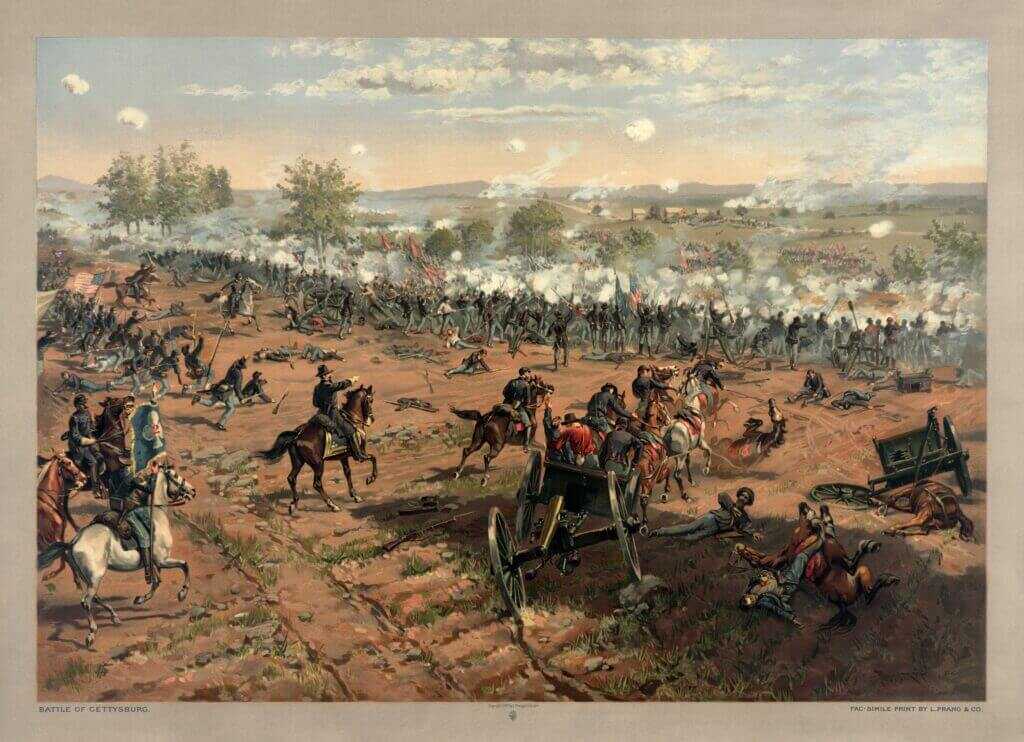

It was the summer of 1864, and the fight was going badly for the Confederacy. After some promising initial gains, the tide had turned the previous summer at Gettysburg. Defeat at Vicksburg around the same time had sealed the deal. By any reasonable metric, the war was lost. However, there yet remained quite a lot of bloody dying to be done before the details were fully resolved.

By this time, war had fully engulfed the American Deep South. General Grant was moving toward my hometown of Oxford, Mississippi, with murderous intent. Now three years into this bitter conflict, everyone knew what that entailed.

In addition to the inevitable wanton pillaging to be found in any war, Grant had a reputation for burning county courthouses as he came upon them. There was little to be gained from this incendiary practice either tactically or strategically.

However, such conflagrations did reliably destroy the land and marriage records. This kept the gentry, most of whom were off fighting with their Rebel units, from reliably verifying land ownership and familial connections. In a renegade country already ravaged by total war, this practice injected just a little bit more madness.

The Player

Colonel Samuel Evan Ragland was born in Halifax County, Virginia, in 1811, a mere 35 years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence. At some point, he made his way south to Mississippi with a few relatives, ultimately procuring a nice piece of bottom land outside the small town of Delay.

This is rich, fertile dirt, the product of millennia of topsoil deposition from areas upstream via the nearby Yocona River. The same stuff reliably produces bountiful crops of soybeans, corn, and cotton to this very day.

The Wife

Along the way, Sam Ragland married Elizabeth Hobson, and they established a home. As was often the case with landowners during this time at this place, that home included a number of African slaves. Prior to the invention of ubiquitous farm machines, agriculture on an industrial scale seemed otherwise impractical. However, for these sins, the Ragland family would soon pay most dearly.

When the first shots rang out at Fort Sumter, Sam Ragland was already fifty years old. Given the abysmal state of infant mortality, life expectancy for a man was only 39 years at this sordid time. The argument could be made that Sam Ragland might have been better off sitting this one out. However, despite the flawed nature of his cause, Ragland was nonetheless a patriot. By 1864, he was a full Colonel in Pemberton’s Confederate cavalry.

Deployed as he was sowing chaos alongside John C. Pemberton, Ragland still got sporadic news from home. When he heard that Grant was moving on Oxford, he took his leave and moved with all dispatch back to Lafayette County.

Arriving in the nick of time, he loaded all the land records from the courthouse up in a wagon and trundled them off to his rural home some dozen miles to the east. There, he secured the documents in his root cellar while the Oxford Square and its associated courthouse were predictably incinerated.

Greed, the Infernal Engine

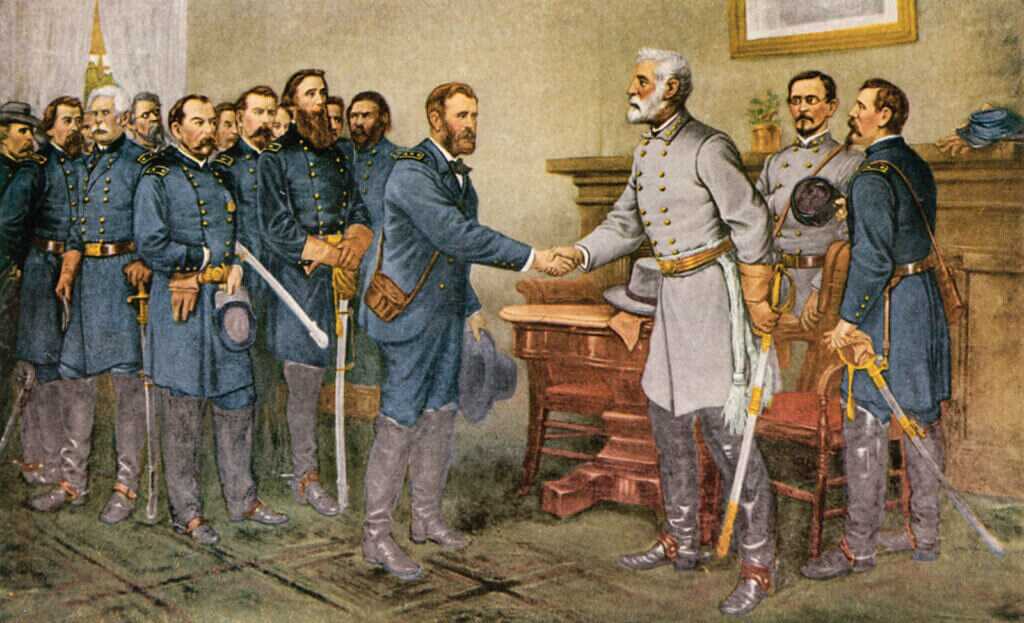

In due time, this war, like all others, finally ground to its gory terminus. With Lee’s capitulation at Appomattox, Sam Ragland, now 54 and haggard from years of campaigning, returned home to his wife.

The Rebels had been soundly beaten, and the victors dictated the terms. That meant that the Ragland family slaves were now rightfully free. They subsequently set themselves up nearby in an awkward, unequal world, trying to redefine themselves amidst social and cultural convulsions simply without precedent.

Throughout it all, Ragland retained custody of those county records. The courthouse was now a charred, empty lot, and the beaten South lacked the resources to rebuild. The fact that these records were there was hardly a secret. Anyone who cared knew this. However, at some point, the story morphed into legend, with disastrous results.

Word somehow got around that, in addition to the real estate documents, Sam Ragland had also stashed away a small fortune he had somehow brought back from the war. The details were fuzzy. However, nobody had anything, and money meant hope. To a modest group of recently emancipated slaves, that temptation became too great to resist.

The Crime

The specific details have been lost to time. What is known for certain is that this group of freed slaves approached the Ragland property via stealth, intending to liberate the swag purported to be secured within.

The cellar where the records were kept has been referred to as a vault, but the specifics are sorely lacking. Regardless, at some point during the prosecution of this enterprise, Sam Ragland discovered the burglary. Violence ensued, and Sam’s wife, Elizabeth, was killed. Sam was himself badly wounded, and the murderers fled empty-handed into the nearby swamps.

Old West Law

Understand, this was a different time. One could not just dial 911 and expect Law Enforcement to descend upon a crime scene to make things right. In Mississippi, in the first year following the Civil War, there was very little remaining in the way of recognized infrastructure. If justice were to be found, it would have to be done informally.

Now both heartbroken and enraged, Sam Ragland bound his wounds and called upon his neighbors. Together they formed a posse and struck out into the nearby swamps in pursuit of Elizabeth’s killers.

These were hard men who had only recently fought a long and bitter war against a determined enemy. They rounded up the culprits in short order. Disinclined to avail themselves of whatever vestigial judicial apparatus might even exist in this place at this time, Ragland and company simply strung the captured miscreants up from some local trees. Once the bodies ceased their twitching, the vigilantes unceremoniously disposed of them in the nearby Yocona River.

The Aftermath

Sam Ragland buried his wife in the family plot and, in due time, moved on from the sordid events of 1866. He later remarried and fathered another son. The identity of the murderers has been irretrievably lost.

Family Cemetary

There is a small, well-maintained family cemetery right down the road from where we live. My wife and I walk together every day I’m not at work, and the weather is nice, so we resolved to do some exploring. What we found was a veritable goldmine of local history liberally intermixed with pathos.

Elizabeth Ragland was 52 years old when she was killed. Her vengeful husband, Sam, ultimately passed in 1894 at the ripe age of 83. There was no readily discernible evidence to be found in the plot of his second wife or subsequent child, though there were ample demised Raglands in attendance.

Per the headstones, RJ Ragland, presumably a brother or cousin, served in Company D, 3rd Regiment of the Mississippi Cavalry. He died in 1883 at the age of 60.

Evan Ragland, likely the first son of Sam and Elizabeth, was born in 1838, served in the 4th Mississippi Cavalry, and died in 1917 at 78. Their graves remain well-maintained to this day. One George Marshall Lynch had a particularly poignant story.

George Lynch married Miss Martha Ragland, who died in 1869 at age 25. He then wed Martha Adams, a local lady some fifteen years younger than he. She subsequently succumbed in 1909 at age fifty. George tragically outlived both of his cherished Marthas. All of this heartbreak you could see quietly etched into these old humble stones.

Ruminations

Cemeteries tell stories, and this was a great one. Right down the road from where I raised my kids, some 158 years ago there was committed a crime most heinous. A woman perished, and her husband was subsequently thrown into a feral rage. The perpetrators were duly apprehended and strung up with minimal fanfare, their cooling corpses disposed of like those of animals.

Such frontier justice was a most brutal thing indeed. All remaining then endeavored to get on with their lives. Sam Ragland’s liberation of the land records back in 1864 is the only reason land ownership in Lafayette County, Mississippi, can be tracked back to the days before the American Civil War today.

The American Deep South is the best place in the world to live. I have traveled the planet as a soldier and do not make such a lofty claim glibly. However, there was once a most horrible darkness in this place. Stark evidence of this fact can be found in a well-maintained family plot at the end of a gravel track just west of County Road 445, right down from Oxford, Mississippi. Sometimes the most amazing things do happen right in your backyard.