Category: Well I thought it was neat!

In a 2010 article in the Marine Corps’ Leatherneck magazine about the Marine Corps’ competitive shooting program, author Ron Keene cited several shooters who confirmed that in addition to the inter-service prestige that is accrued by participation in these contests, the program has an overriding benefit to the Corps at large in terms of overall marksmanship training.

This phenomenon has been known for many years, as the successful competition shooters are often the same coaches who teach marksmanship skills to all Marines. Marines are known worldwide for their skill with firearms, and it is generally accepted that Marines have always been outstanding marksmen and have always won any shooting contests that they have ever entered.

However, this is not quite the case. By the 1930s, Marine Corps publicists had begun the legend that Marines had always been crack shots with musket and rifle, pointing to unsupported exploits of Marine “sharpshooters” on board ships during the American Revolution and the War of 1812. In most instances, this was not what really happened. Although some early accounts refer to Marines’ abilities with the musket, most do not.

The legend may have had some basis in fact, as an example of this can be found in a laudatory letter that surfaced about twenty years ago. Written by a Marine officer after the Battle of Bladensburg, it recounted how the field in front of the Marines’ line was strewn with the corpses of British soldiers, and the writer congratulated the Marines of that detachment for their prowess with the musket. However, it must be remembered that a Marine wrote this letter to a fellow Marine, so its objectivity may be suspect.

During the American Civil War, the first Marine to be awarded the Medal of Honor was Cpl. John Mackie for his exploits during the battle of Drewry’s Bluff. He blazed away at Confederate Marines on shore with his Springfield musket while on an ironclad ship which was running the gauntlet of the forts around Richmond, Va. However, few other instances can be found where Marine Corps marksmanship with shoulder arms was at all noteworthy.

Indeed, when Marines fired a volley at a mob of insurrectionists in Washington, D.C., during the election day riots of 1857, they killed several bystanders, but few of the rioters at whom they were shooting. In 1899, the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Major General Charles Heywood, was dismayed to find that out of a full strength of about 6,000 men, only 89 officers and enlisted men qualified as marksmen or sharpshooters.

Marines simply did not have the opportunity to practice with their rifles, since Marine barracks were established at Navy Yards in major coastal cities such as Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Washington and Norfolk among others. At these locations, Marines did not have access to open fields or shooting ranges. Although gallery practice ammunition was available, indoor shooting with black powder .45 caliber rifles does not replicate the real thing.

Additionally, small arms practice while on board ship is a difficult and unrewarding endeavor. Finally, prior to 1896, Marines who felt a need to gain extra practice had to purchase their own ammunition from the Quartermaster. Heywood’s solution was to appoint Major Charles Laucheimer as the Inspector of Target Practice, and he then directed that the Marine Corps improve in this field. Laucheimer inaugurated the program by entering a rifle team in a competition at Sea Girt, N.J., in 1901.

This was the Marine Corps’ first shooting match. Among his team members was a future commandant, then Lt. Thomas Holcomb. The Marines were firing the newly adopted Krag-Jorgensen .30 caliber rifle, which had recently replaced the M1895 Lee Navy 6.5 mm straight-pull rifle that was carried by Marines during the Spanish-American War. The results were disappointing. The Marines placed sixth out of eleven competing teams, and their final results were far below the winner, the National Guard team from Washington, D.C.

Upon Heywood’s retirement in 1903, he was replaced by then-Brigadier General George F. Elliott, an even more enthusiastic promoter of marksmanship. Among historians, Elliott is credited as being the father of the Marine Corps marksmanship program. Drawing on the knowledge and skill of civilian shooters, most notably “Doc” Scott, a Maryland dentist, the skill of Marines training at headquarters in Washington, D.C., steadily improved as did the abilities of Marines stationed afloat and ashore.

One of the incentives at the time was an authorization in 1906 to pay marksmen an extra one dollar per month, two dollars for sharpshooters and three dollars for those who qualified as expert. This “beer money” was above the basic privates’ pay of 18 dollars per month. Very importantly, about this same time, the Marine Corps adopted the Army’s Model 1903 .30 caliber Springfield rifle.

The adoption of this rifle had far-reaching effects, and it became the measuring stick against which all other contemporary rifles were judged. Based off the Mauser action, the Springfield was nearly unique among the service rifles of the world at that time. With the exception of the British Lee Enfield, other military rifles then in service around the world (the French Lebel, the Russian Mosin-Nagant, the Japanese Arisaka and the Mannlichers and Mausers carried by nearly everyone else) had rear sights that were only adjustable for elevation.

Conversely, the rear sight of the Springfield and the Lee Enfield could also easily be adjusted laterally for windage. This feature gives the shooter the ability to compensate for the effect of the wind on the bullet at long range. In fact, some American service rifles had incorporated this feature as early as the 1870s. The Buffington rear sight that was introduced in 1884 on the single-shot .45 caliber “Trapdoor” rifle used a dial knob, which made windage adjustments very simple during battle.

Although the sighting system on some of the later models of the Krag-Jorgensen rifle was an improved version of the Buffington sight, the sight on the new M1903 Springfield was a marvel of minute adjustments. It was a rifle designed for precision shooting, and the Springfield ’03 soon reached a position of near-holiness among Marine shooters, a place it held until replaced by the semi-automatic M1 Garand rifle during World War II.

With the new rifle, Marines’ skill at arms began to improve dramatically in subsequent rifle matches, and the intensive program continued to show steady improvement at a number of different shooting competitions. The Marine Corps’ rifle team took fourth place in the 1905 National Matches, and then placed second in 1910. However, the Springfield rifle and Laucheimer did not do it alone.

Laucheimer was joined by a number of Marine riflemen who went on to be distinguished marksmen. Among them was then Capt. Douglas C. McDougal, who joined the program in 1909. McDougal’s principal duty during his two-year tour at Marine headquarters was as instructor of rifle marksmanship, and he was the captain of the Marine Corps rifle team’s first triumph of winning the National Matches in 1911.

However, the person most responsible for the dramatic emergence of Marine Corps excellence in marksmanship was William C. “Bo” Harllee, and he made it happen through his devotion to the program, his innovative approach to education and his unbounded energy to ensure results. Indeed, there are few other instances in history where one man can make such an incredible difference in an institution, and literally change everything so quickly. William Harllee stands out among military men.

A southerner by birth, he was raised in the tradition of the “Lost Cause” by his uncles, all of whom served in the Confederate Army. After graduating from high school in rural Florida, the imposing, lantern-jawed Harllee attended South Carolina’s state military academy, the Citadel, for a year until he was dismissed for accruing too many demerits. He then studied at the University of North Carolina.

When his family could not afford further college tuition, he became a schoolteacher in Florida until he obtained admission to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1897 which was his life’s ambition. Unfortunately, he soon found himself at odds with the academy’s superintendent over his refusal to bend to what Harllee considered pettifogging rules, and he was dismissed in 1899 for again acquiring too many demerits.

He then enlisted in a Texas volunteer regiment and proved his worth in battle as a sergeant during the Philippine Insurrection. Appointed as a lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps in 1900, he began a stormy, but significant career with the Marines. He served in the Boxer Rebellion, and then returned to the Philippines to help quell the ongoing insurrection.

While he commanded the Marine detachments of the USS Tacoma during the Cuban pacification of 1906, and the USS Florida during the landing at Vera Cruz, Mexico, in 1914, the campaign for which he is most remembered was his controversial effort to ensure the pacification of the Dominican Republic in the early 1920s. Aside from combat, Harllee was also instrumental in directing both the Marine Corps Publicity Bureau and the Marine Corps Institute, in their formative years.

However, his most noted contribution to the Corps was in marksmanship training. While stationed in Hawaii in 1904, Harllee was dismayed at the lack of opportunities for the Marines of his command to practice shooting with their rifles, an continual problem for the Marine Corps since its founding. As noted before, Marine barracks were located at naval bases in large cities and the Marines stationed in these barracks would have to travel to rudimentary or makeshift shooting ranges in the surrounding countryside for any marksmanship training.

Harllee succeeded in building a modern range in Hawaii, all with Marine labor and a minimum outlay of government funds. Moreover, Harllee also began an intensive program of instruction for the Marines under his command. Based on his firm belief that the successes of the Confederate Army during the American Civil War were in no small part due to the shooting abilities of its troops, who were for the most part raised in the rural traditions of hunting and shooting, Harllee energetically began to teach his Marines the principles of rifle shooting on the new range.

His teaching methods harkened back to his days as a rural schoolmaster, when he taught under the supervision of a German immigrant professor, Dr. Frederick Buchholz, and he adopted the professor’s “Seven Laws of Teaching.” Indeed, Comdt. Thomas Holcomb later commented that Harllee was a “born instructor—he could teach anything.” The program succeeded and Harllee came to the attention of the Marine Commandant.

After a brief stint in Chicago, where Harllee successfully started up the Marine Corps’ first publicity bureau to assist with recruiting, he was summoned to Washington in 1908 and assigned as the captain of the Marine Corps’ rifle team. The Commandant had some misgivings about him, as Harllee was well known as a forthright and focused Marine, who would often bypass regulations he found to be irrelevant, and officers he considered to be martinets, to complete his assigned mission.

Moreover, he had never lost his appreciation for the stunts that had landed him into trouble at the Citadel and West Point. But Harllee undertook the mission to excel. Harllee’s first important improvement was to insist on absolute teamwork among the Marines on the rifle team. After several incidents in which team members were disciplined or removed, it was apparent that every man was to help his teammates, and personal egos were to be left at the doorway.

Secondly, he tried a novel experiment to reduce the pressure that a shooter experiences in a very demanding high-profile match. He kept his men partying and drinking until the wee hours the night before a match, so that they would sleep soundly when they finally did go to bed and were too tired the next day to get nervous. This approach must have worked, as the Marines kept winning match after match.

The lack of suitable rifle ranges was still a problem, and the Marines had to shoot on a range at Williamsburg, Virginia, about 150 miles southeast of Washington. In 1909, the Commandant ordered Harllee to build a modern shooting range on a parcel of land in Maryland, about 30 miles south of Washington. Again, Harllee successfully built a modern range, complete with barracks, mess hall and even a vegetable garden, which opened as the Winthrop Range in 1910.

The range was an instant success, and Marines began putting it to good use. The Winthrop Range was in use until the Marine Corps opened its new training facility across the Potomac River in Quantico, Va., in 1917. Amoung the dignitaries to fire on the Winthrop Range was the then Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt. Moreover, Harllee hit upon the novel idea of opening the range to civilians, and he initiated a program in which men and women could take a chartered steamship from Washington.

These men and women would learn the rudiments of firearms safety and handling from Marine instructors on board, then learn to fire the standard infantry rifle on the range. Harllee felt very strongly that the defense of the nation could be enhanced by familiarizing its citizens with firearms, in the event of a national emergency or general mobilization, and he worked very closely with the rejuvenated National Rifle Association to further this effort.

One of William Harllee’s greatest contributions was his authorship of the pocket-sized “U.S. Marine Corps Score Book and Rifleman’s Instructor” manual which became the basis for marksmanship training for the next 25 years. Indeed, parts of it were incorporated in the U.S. Army’s manual, as well as those used by Great Britain, Cuba and Haiti. The manual was the standard for all new Marine recruits during World War I.

During this period, the Marine Corps moved from one recruit depot in downtown Washington D.C., to depots on both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. Originally sited in Philadelphia, Penn., and then in Norfolk, Va., in 1911, the east coast depot was consolidated at Parris Island, S.C., in 1915. The west coast recruit depots had been set up at Bremerton, Wash., and Mare Island, Calif., but they had been consolidated at Mare Island (near San Francisco) by 1912.

This function moved to San Diego, Calif., after World War I, where it remains today. Harllee’s work paid great dividends during World War I. When Marines of the Fourth Brigade stopped a German attack at Les Mares Farm, on the eve of the battle of Belleau Wood, Allied observers were incredulous. The Marines, in prone positions, were calmly firing at the attacking Germans over 600 yds. away and the Marines completely disrupted attack after attack. Marines now truly were legendary riflemen, and have been such to the present day.

This article is based on a paper that was presented at the 2010 annual conference of the International Committee of Museums of Arms and Military History, held in Dublin, Ireland. See http://icomam.mini.icom.museum/the-magazine/ for more articles about historical firearms, edged weapons, armor, artillery and fighting vehicles.

For further reading, see “Marine from Manatee: A Tradition of Rifle Marksmanship” (1984), written by Col William C. Harllee’s son, RAdm John Harllee USN.

The author thanks Owen Conner and LtCol Robert M. Sullivan (Ret) of the National Museum of the Marine Corps, as well as Dirk Haig of ChinaMarine.org, for their assistance in the preparation of this article.

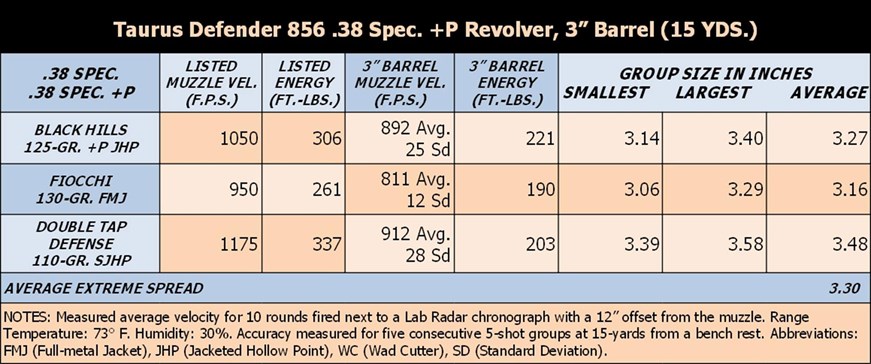

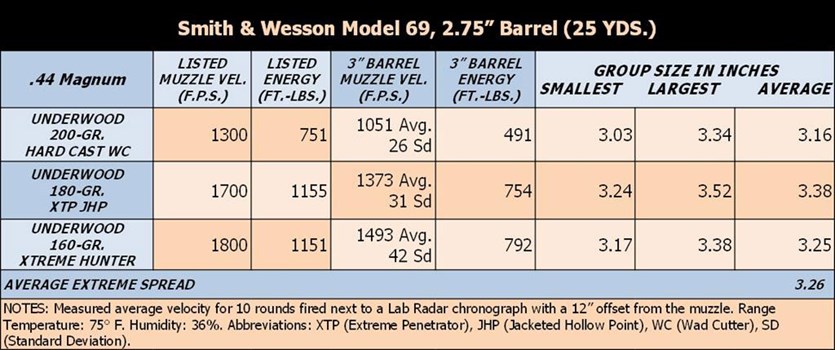

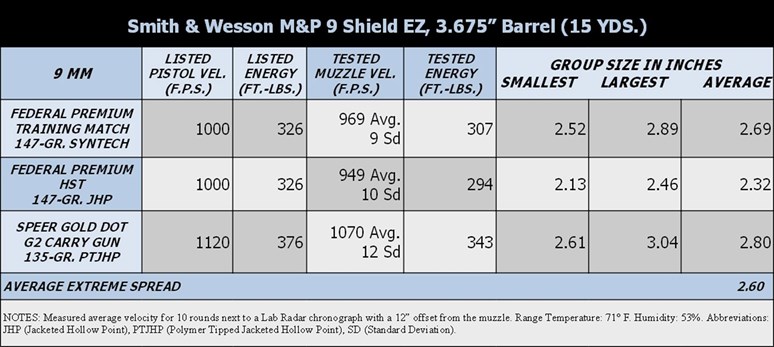

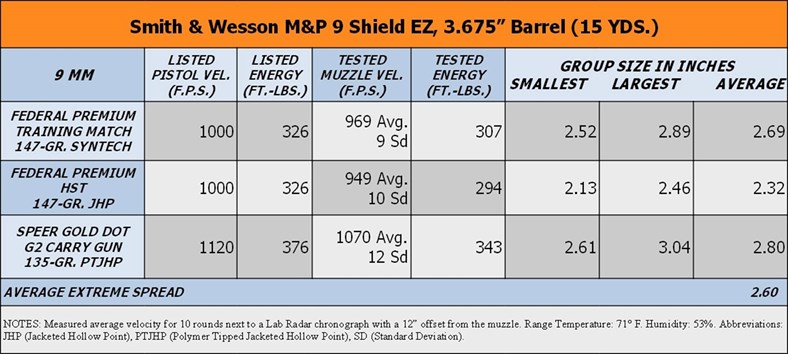

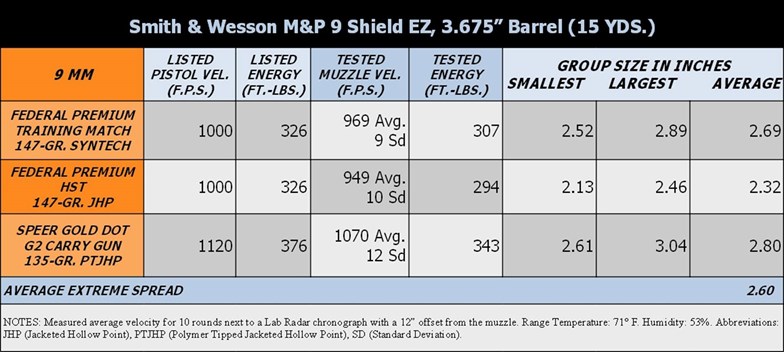

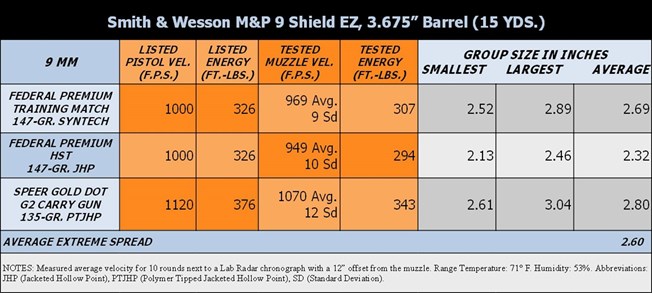

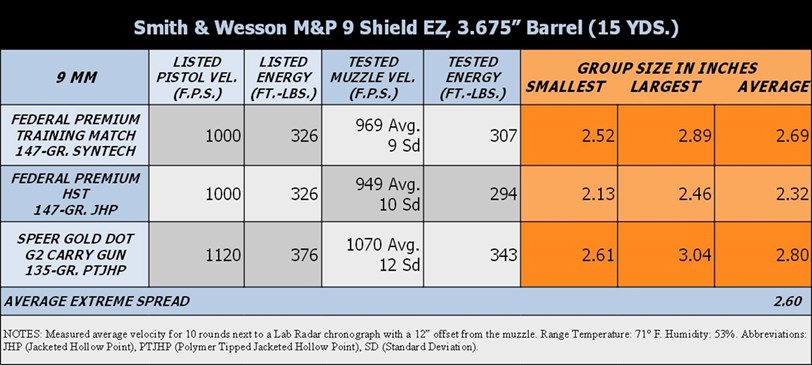

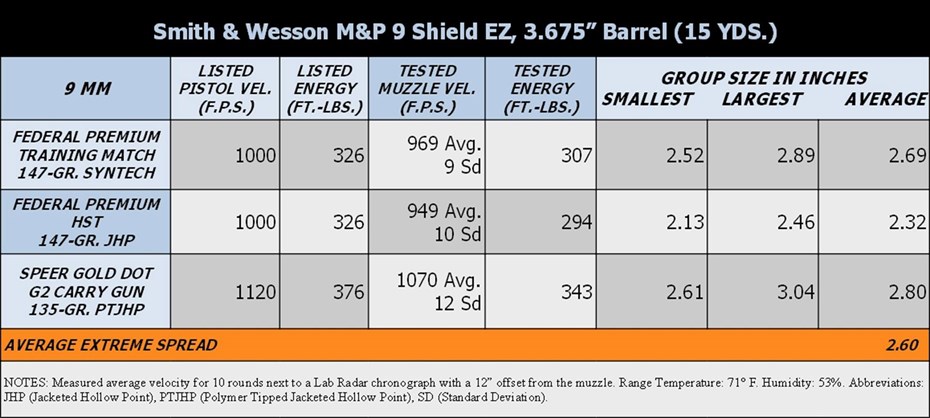

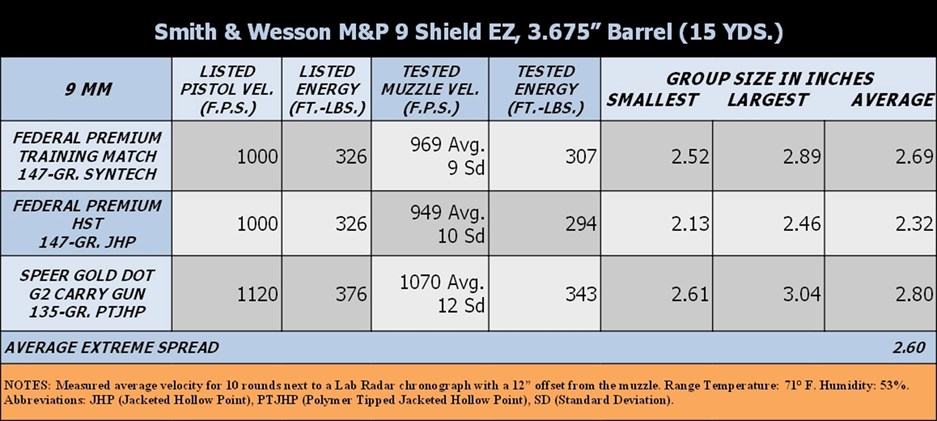

The first time I saw a table like this in a magazine (it was a few years before the Internet was a thing) I couldn’t see the forest for the trees! There’s a whole lot of jargon, numbers, abbreviations and behind-the-scenes-science packed into these things. At that time, it wasn’t clear how the sections of the tables fit together or how the information was even useful to me in trying to decide which gun to buy.

Luckily for me, I had a good friend who knew his way around these tables sit down and walk me through how to use them. It was just enough information to understand the tables without a deep dive into the chemistry, physics and mathematics behind them. This article is intended to do for you what my friend did for me all those years ago.

To aid the novice enthusiast with this walk through, I’ll be making some simplifications and generalizations, with a focus on defensive handguns. For those of you who have more experience, or PhDs in related scientific fields, please remember that the goal here is to turn the key in the ignition. We’ll save calculating the torque force required to rotate the key (τ = N m) for next semester.

The Purpose of Performance Tables

How we go about measuring performance depends on what’s being measured. Generally speaking, there are two main types of performance we’re striving to measure when testing a handgun: bullet energy and handgun accuracy. But it takes several different sources of information to get these metrics, including the type of ammunition for which the gun is chambered, barrel length, bullet weight, and data collected from tests conducted at the shooting range. Keep in mind, there is no fixed, worldwide standard for measuring handgun performance. Americans use different metrics than Europeans, and American publications use different test standards depending on who is publishing the gun review. I’ll point out what standards were used to produce the M&P9 Shield EZ pistol performance table as we go along. Now let’s take a closer look at each section of the performance table.

Title Bar

The title bar, located at the top of the table, lists the model of the handgun tested, the gun’s barrel length and the target distance in yards. The barrel length is important because it has a direct effect on both the metrics we’re looking for: bullet energy and accuracy. Longer barrels give the gun powder in the cartridge more time to burn and build up pressure. As a result, a bullet fired from a 6″ barrel is going to be traveling faster and have more energy when it leaves the gun than a bullet launched from a 2″ barrel.

A longer barrel also has more time to stabilize the bullet. This will keep it on target at greater distances for improved accuracy. Short barrels are easier to carry concealed but come with the trade off of less accuracy at extended distances. So how far should the targets be from the muzzle of the gun for accuracy testing? I followed the NRA’s American Rifleman guidelines for the tables shown here. For handgun barrels 2″ or shorter, the test targets are set 7 yards away from the muzzle. For barrels between 2″ and 4″ in length, the target is moved out to 15 yards and if the barrel is 4″ or longer, the targets are pushed back to 25 yards.

Ammunition Information Column

At the top of this column, on the left side of the table, is the caliber of ammunition the test gun fires. The three boxes below that Iist the brand (Speer Gold Dot), load name (G2 Carry Gun) bullet weight (135-GR.) and bullet type (PTJHP: Polymer Tipped Jacketed Hollow Point). The bullet’s weight is measured in grains, which are abbreviated -GR. It’s an archaic unit of mass based on, I kid you not, the weight of a single grain of barley. To bring it into a more modern perspective, 437.5-gr. equals one ounce.

The bullet weight is listed here because it plays a role in calculating how hard it will hit the target. There are quite a wide variety of different bullet types to choose from these days, but that’s a discussion for another article. Suffice it to say that the bullet-type abbreviations are spelled out in the Notes section of the table.

Understanding Bullet Energy

Calculating the amount of energy a bullet has just as it leaves a gun gives us a yard stick for how effective it’s going to be as a defensive tool, as well as what it’s going to feel like to shoot it. Additional tests and metrics are needed to fully quantify the ballistics of a bullet, meaning its flight path and what the bullet is likely to do when it strikes a target. But a bullet’s energy at the muzzle of the barrel is a good starting point.

Muzzle Energy Columns

Let’s talk about effectiveness first. The purpose of a defensive handgun is to stop a threat from harming us, whether it’s of the 4-legged or 2-legged variety. It does so with a transfer of kinetic energy (which is the energy of mass in motion) from the gun into the intended target via a fast moving bullet. As the bullet strikes, it transfers kinetic energy into the intended target, damaging it to some degree.

Just how much kinetic energy is produced at the muzzle of the gun, often shortened to just “muzzle energy” will play a role in how much damage it does. If the bullet strikes with too much energy, it could pass right through the threat (over penetration) and keep on going with the undesirable potential of striking an innocent bystander. But if the bullet’s energy is too low, it will not penetrate deeply enough into the target (under penetration) to effectively stop the threat. Determining the “just right” amount of muzzle energy for a defensive handgun continues to be a hotly debated topic.

In order to measure a bullet’s muzzle energy we’ll need to know the bullet’s mass and its velocity. As mentioned earlier, the mass is measured in grains (GR.) and is provided by the ammunition manufacturer.

A bullet’s velocity is determined by firing shots across, or next to, the sensors of a chronograph placed close to the gun’s muzzle. The speed is shown here in the number of feet traveled in one second (F.P.S) while some charts will use meters per second (M.P.S). Some bullets will travel slightly faster while others will be a bit slower because no two powder charges are exactly alike. That’s why it is customary for reviewers to fire multiple rounds of ammunition from the same box and then average the velocity of those shots together for a final number. In this case, 10 consecutive shots were fired for each load tested.

The bullet’s mass (GR.) and average velocity (F.P.S.) is then pumped through a kinetic energy algorithm (like this one: Ek= 1/2mv2) to get the muzzle energy, which is measured in foot-pounds (FT-LBS.) This unit of measure represents the energy required to lift one pound of weight the distance of one foot. The larger the muzzle energy number, the harder the bullet will strike the target.

Felt Recoil

This brings us to how it’s going to feel to shoot the gun. As Newton stated in his Third Law of Motion, “For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.” This means that when a cartridge is fired, it generates pressure in two directions. The bullet is pressed forward out of the gun while the gun itself is pressed backwards into the shooter’s hands. That sharp jerk, or kick, is what we call recoil. And how that recoil is perceived by the shooter is called felt recoil. How much felt recoil is too much for comfort? It depends on the person pulling the trigger. But those loads with greater levels of muzzle energy are going to kick harder than those that produce less energy.

Listed vs. Tested Data Columns

The table shown here has two sets of muzzle energy information, Listed and Tested. The “Listed” columns incorporate the pistol-length barrel performance data published by the ammunition manufacturer. Companies test their ammunition in laboratory conditions in order to make sure that it is safe to use. Most writers don’t include this information in their tables, but I find it to be a useful reference point. The “Tested” columns are the results from shooting the test gun at the range with the three listed loads of ammunition. In less-than-ideal, real-world conditions in which the barrel of the gun may be shorter than the test barrel used in the laboratory, the Tested velocity and energy levels are usually lower than the Listed results.

The two Federal 9 mm loads shown in this table have the same bullet weights and listed performance data. The Syntec is a less expensive practice-grade load while the HST is a premium defensive hollow point. They are “ballistically matched” so that the practice grade ammunition will produce recoil and accuracy on par with the hollow point loads in order to save money when practicing at the range. Based on the averaged results, both loads are statistically similar enough to say that yes, they are ballistically matched as advertized.

Just below the 10-shot average velocity number in the Tested velocity column, there’s an additional number with the abbreviation Sd next to it, which stands for Standard Deviation. The short answer for Standard Deviation is that it measures the consistency of the ammunition’s velocity. A smaller Sd means that the 10 rounds fired across the chronograph aretraveling at similar velocities with a predictable level of felt recoil. As the Sd gets larger, it means some cartridges had more powerful powder charges than others causing the levels of felt recoil to go up and down. This can detract from good shot placement. The Sd numbers shown here are fairly low showing that all three 9 mm loads produced consistent energy levels.

Group Sizes Columns

Understanding muzzle energy is all well and good, but not all that useful if you can’t hit what you’re aiming at. That’s what accuracy testing is all about. The most common approach is to fire a few shots in a row aimed at a particular location on a paper target. The bullet holes clustered together in that location are called a group. The distance between the two bullet holes that are the farthest apart from each other is measured in inches (or millimeters) and recorded. Firing just one group isn’t terribly scientific because groups tend to vary in size, just as the bullets tend to vary in velocity. In this case, a total of five groups of five shots each were fired from a seated position using a bench-rested handgun support to stabilize the pistol. Under the Group Size heading, the first column shows the smallest of the five groups followed by the largest group and the five-group average.

So what does good defensive handgun accuracy look like? There is no generally accepted industry-wide standard for acceptable accuracy but here is the rule-of-thumb that has served me well over the years. If a handgun, and the ammunition tested, can produce five shot group averages around 3″ to 3.5″ in size at a given target distance (7 yards, 15 yards or 25 yards), then the gun and ammunition are doing their jobs properly. If the groups are smaller than 3”, you’ve got yourself a winning combination.

However, if the groups are consistently larger than 3.5″, some adjustments are in order. There may be a mechanical problem with the gun, like a loose or crooked rear sight. The ammunition may be of a low quality or it’s a poor fit for the gun. If that’s the case, it should be traded out for a different brand or bullet weight. It may be that the shooter is trying to shoot past a reasonable distance for the gun’s barrel length, like shooting a tiny 2” barrel pocket pistol at 25 yards when 7- to 10 yards would be a better fit for the gun’s capabilities. Last, but certainly not least, it could be the shooter’s technique. Additional training and practice is often the key to getting groups down to the size they need to be.

Average Extreme Spread Bar

The Average Extreme Spread is a fancy name for a summary of the accuracy results. The three numbers in the Group Size Average column are averaged together to get the number you see, which in this case is 2.60″.

Notes Section

The information displayed at the bottom of the table is for the more detail oriented readers. It shows the type of chronograph used (Lab Radar), in addition to air temperature and the humidity levels since they can have an effect on the performance results. Finally, there’s a list of the bullet style abbreviations found in the far left column and a mention that Sd stands for Standard Deviation.

Putting Performance Tables to Work For You

Now that you know the purpose of performance tables and what the lingo means, how can they be useful to you? Much like a one-page resume or a quick snapshot, these tables won’t tell everything there is to know about a gun you’re investigating. But they do provide just enough information to see if you want to learn more about that gun or take it for a test drive. I’ve found performance tables to be especially handy when comparing two different guns or calibers to see which would be a better fit for my needs. Here are the performance tables for two concealed carry revolvers that I tested which are chambered in different calibers. To test your newly acquired skills, take a look and see how they compare for accuracy, muzzle energy and felt recoil.