Category: Well I thought it was neat!

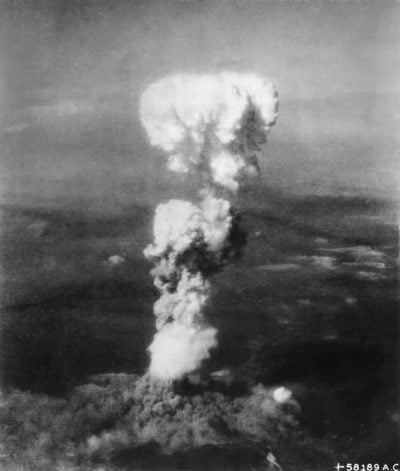

An image captured from the B29 chase plane Necessary Evil

of the actual detonation of the first atomic bomb over Hiroshima.

The law of conservation of mass states that in any closed system the ultimate mass of a system must remain constant over time. The law of conservation of energy posits that the total energy of an isolated system also must remain constant. Mass and energy are therefore said to be conserved over time. Both can change forms, but mass and energy can be neither created nor destroyed. They simply change from one state to another.

Take a match as an example. You strike a match and allow it to burn. What’s left is smaller and different from the original match. However, that excess mass didn’t just disappear. It changed forms. As the compounds in the wood degraded they gave off energy and some portion of it turned into a series of gases. That original stuff is not gone. It’s just different.

In the world of physics, this isn’t only not a good idea. It’s the law. However, there is one glaring exception. Albert Einstein codified the details within his extraordinary equation E=MC2.

In the case of nuclear fission, a small amount of matter actually transforms directly into energy. Unlike our burning match example, some mass of fissile material consumed in a nuclear reaction no longer exists in our universe. This matter is physically transformed into energy. The ratio is driven by that equation where E is energy, M is rest mass or invariant mass, and C if the speed of light. As the speed of light is a big number and you are squaring it, the resulting amount of energy you get for a small amount of transformed matter can be truly astronomical.

As weird as all this seems, we can see the practical results clearly enough. It is this reaction that propels American aircraft carriers and nuclear submarines. It also drives nuclear power plants.

Despite their simply breathtaking size, aboard a nuclear-powered ship, a small amount of fissile material powers everything from propulsion and catapults to hot water and laundry. Producing 200,000 horsepower non-stop to power the USS Gerald Ford for a week requires less than nine pounds of enriched uranium fuel. These massive ships are expected to run for a quarter century without refueling. The tiny amount of fuel that is actually turned into energy in a nuclear reaction is even smaller yet. Now, hold that thought.

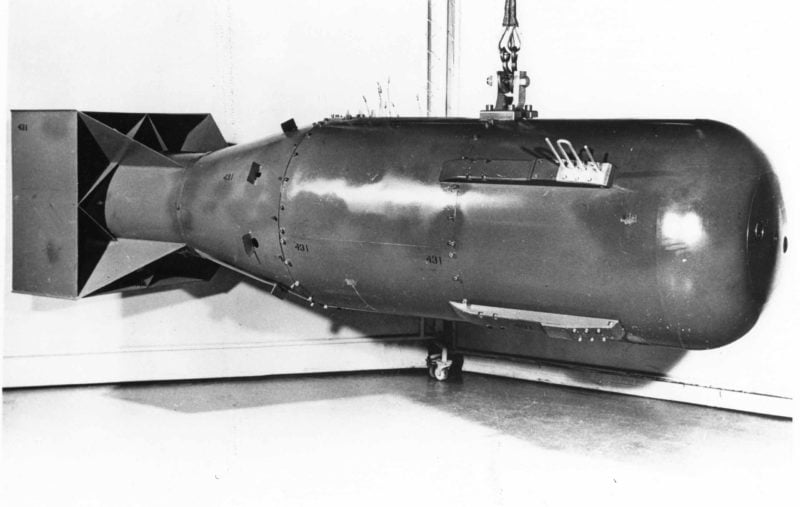

The Little Boy Test

The atomic bomb unleashed on Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945, was called Little Boy. This was a relatively simple gun-based device that burned enriched Uranium-235. The term enriched stems from the fact that only about one part in 140 of naturally-occurring uranium is the particular desirable U-235 isotope.

Building the bomb was fairly easy. Harvesting that specific uranium isotope was hard. That’s what the Iranians have been hell-bent on doing for the past decade.

Little Boy was little more than a stubby gun. An enriched uranium target sat at one end and a smaller uranium projectile resided at the other. At the point of detonation a chemical explosive fired the projectile down the internal barrel into the target and achieved critical mass for a spontaneous detonation.

The plutonium-based bomb, Fat Man, which dropped on Nagasaki three days later, was a more complicated implosion design. It was this mechanism that was detonated during the Trinity test in New Mexico. The first operational test of the Little Boy bomb was the Hiroshima attack. Most of the uranium used in Little Boy came from the Shinkolobwe mine in the Belgian Congo.

A Single Paperclip

Once ready to go Little Boy sported an all-up weight of 9,700 pounds. Of that mass was 141 pounds of enriched uranium. The average level of enrichment was around 80%. Upon detonation around two pounds of uranium underwent nuclear fission. Of the bit that burned, only 0.7 grams or around 0.025 ounce was actually transformed into energy. This is roughly the same mass as a dollar bill or a paperclip.

The bomb was deployed from the B29 Superfortress Enola Gay at 0815 in the morning. It fell for 44.4 seconds before its dual redundant time and barometric triggers fired the ignition charges. The weapon detonated 1,968 feet above ground, and the resulting explosion released 63 Terajoules’ worth of energy — the equivalent to 15,000 tons or 30 million pounds of TNT (Trinitrotoluene) high explosive.

The fireball was 1,200 feet in diameter with a surface temperature of 10,830 degrees Fahrenheit, roughly comparable to the surface of the sun. Every man-made structure within a mile of ground zero was instantly pulverized. The resulting firestorm was roughly two miles in diameter. Survivors reported a strong smell of ozone, as though they had been near a powerful electrical arc. This unprecedented explosion killed 66,000 people and injured another 69,000, all for the cost a single paperclip’s worth of enriched uranium.

The following stories were shared by email with permission to publish.

Dear Santa…

Recently, like many of you, I read an article in the news about a sanctimonious mall Santa who thought it appropriate to push his views on a little boy. Specifically, the child asked for a Nerf gun for Christmas. The Santa, even after the child’s mom clarified it was a “Nerf Gun” rather than an actual firearm, continued to press the issue and stated, “No, no guns at all”. Needless to say, the boy was in tears at Santa’s turn.

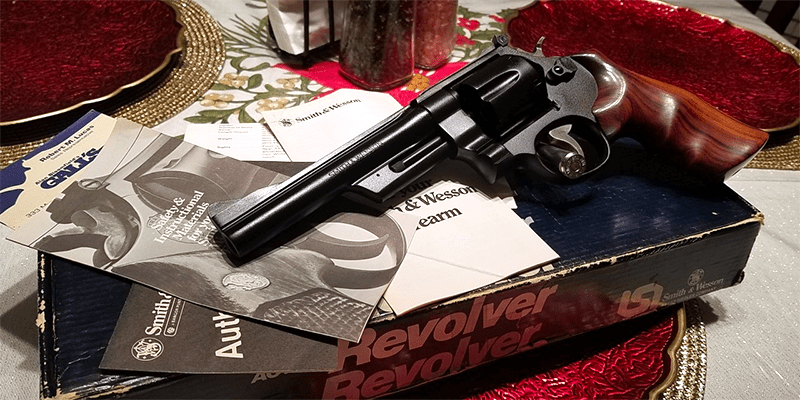

This recent escapade made me reminisce about the first handgun I received as a Christmas gift from my father in 1984 when I was 12 years old — a 6” Smith & Wesson Model 28-3. Growing up in rural eastern Kentucky and the son of a police officer, I can remember loading up in dad’s truck and making the trek all the way to Lexington to pick it out. We went to Gall’s Police Supply (which back then was much smaller than it is today) and handled a 4” Model 15 and a Model 19 before settled on the 6” Model 28. The salesman, whose business card can be seen in the photo with the factory paperwork, took the time to talk with my dad and I about the strength of that big “N” frame and I was hooked!

As most Smith & Wesson aficionados know, the Model 28 was originally released in 1954 as the “Highway Patrolman”. Built much like its sibling the Model 27, it left the factory with a matte finish and devoid of the fine checkering on the top strap and barrel rib present in the 27. Generally, it had a service trigger and hammer unless ordered with the target options of its sister gun. It also only had 4” and 6” barrel offerings rather than the plethora of lengths for the Model 27. In totality, it offered the heft, durability, accuracy and shootability of the Model 27 at a lower price point which made it extremely popular with both law enforcement officers and sportsmen.

The Model 28 was adopted by state police of Florida, New York, Texas and Washington as well as countless municipalities and sheriff’s departments in search of a rugged and dependable sidearm.

The “Highway Patrolman” became the Model 28 when Smith & Wesson consolidated the catalog into model numbers in 1957. After that, it went through three design changes with the first two coming in rapid secession. For this reason, a Model 28 “no dash” will bring a 30% premium and 28-1 is regarded as “very rare” with a “substantial premium” according to the benchmark “Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson, 4th Edition”. Shortly after that Christmas, in 1986, Smith quietly ended production of the Model 28.

Over the years, many Smith & Wesson’s have filled my safes of all degrees of finery and caliber —including a 3.5” pre-27 and pre-19 Combat Magnum — but none can replace that old Model 28-3. Not only is it the handgun I learned to shoot accurate and fast with as a teenager, but it stands in testament to the trust and faith my father placed in me at the age of 12.

In today’s world, if one were to listen to the media or a self-righteous mall Santa, you would be led to believe by entrusting such a weapon to a “child” you would be charting a course for a troubled life. However, the truth is much different. I was brought up to have great respect for the laws that bind society together; the traditions we as Americans hold dear and a reverence for the trust one person places in another. These traits have served me well throughout life as a retired Marine Corps Master Gunnery Sergeant with over 30 years of service still seeking ways I can serve my fellow man. My wife and I also raised two contributing and productive members of society that carry the values I speak of.

So, while I can’t specifically say Smith & Wesson Model 28-3 made all that come true, I can confidently say it does symbolize well-placed trust and faith that led to a life well-lived.

R. Brandon Deskins

Master Gunnery Sergeant

USMC (Ret)

Just Walked In

Working retail part-time at a local gun store, we regularly take used guns in for consignment. Most are outdated models as customers look to replace their self-defense and competition guns, while others are simply trying to make some side cash off unwanted guns they no longer shoot, but, once in a blue moon, a gun crosses our counter that makes everyone stop and take a closer look.

This past week, as I clocked into work, a glossy brown case with gold locks set aside on the counter caught my eye. Like a kid drawn to presents under a Christmas tree, I immediately opened the case to find a large-frame revolver on a bed of red velvet. A closer look revealed it was a .41 Magnum 8” Smith & Wesson Model 57 in pretty good condition. “Oohs” and “aahs” followed as I wiped the drool from my mouth and grasped the large combat grips in my hand and looked down the long, blued barrel to the red ramped front sight. The last finger groove fell right where I’d prefer to place my last digit, but the pistol felt well-balanced in my hand.

Having handled thousands of guns, there’s always something special about picking up an older firearm — especially revolvers. Originally produced between 1964 and the year prior to my birth (1991), it may not have the same mass appeal it once did but remains a classic for those who recognize its history and simplistic beauty. A revolver for a true wheelgunner, I hope whoever takes it home adds to its 30-plus years of Wheelgun Diaries, and I selfishly hope to be the one who gets to give it away.

Joe Kriz

.png)

Young men are stupid. I am certain of this because, back in the early Mesozoic era, I was one. Don’t believe me? Roughly 93% of America’s incarcerated population is male. We are imprisoned at a rate fourteen times higher than is the fairer sex. Testosterone is the world’s most potent poison.

Back when dinosaurs roamed the plains I needed to figure out what I wanted to do with my life. I had grown up devouring everything I could find on World War 2 aviation. I knew I wanted to be a military aviator, but I wasn’t sure what sort. The Internet was but a gleam in the eye of a young Al Gore, so I just read books and talked to folks who had done it. Eventually, I settled upon Army helicopters.

Driving jets was sexy and all, but those rascals were undeniably complicated. I wanted to really fly, not manage some hyper-complex technological system. Army helicopters seemed a bit closer to the Golden Age of aviation in my neophytic view. Additionally, if I didn’t pull it off there seemed to be plenty of other cool stuff I could do as an Army officer.

So, there you have it. I sought out a career path based solely on how cool it would be. Not how amenable it might be to raising a family (hideous) or what sort of retirement it offered (decent, I guess), but rather simply because the job seemed like a rush and I thought I’d cut a dashing figure in a flight suit. You recall I mentioned young men are stupid.

With the benefit of hindsight perhaps I should have worn blue instead of green. The Air Force is commanded by pilots, while the Army is commanded by grunts and tankers. That simple observation makes all the difference in the world as regards lifestyle. As a result of my skewed logic, I ultimately spent a year in the Infantry living like some kind of farm animal, feasted upon some of the most unspeakably vile stuff in survival school, and averaged eight months out of twelve away from home on a good year. However, at least I got to enjoy the inter-service collegiality that comes from being a military aviator.

I did plenty of joint operations wherein I worked with the Wing Nuts of the US Air Force and the Squids of the Navy. I always felt like we enjoyed a productive relationship based on mutual respect. Then on Valentine’s Day 1991, CPT Richard Bennett, flying a USAF F-15E Strike Eagle along with his Wizzo (Weapon Systems Operator) CPT Daniel Bakke, showed the world the insensate disdain in which they held Army aviation. Those guys pulverized an airborne Iraqi helicopter gunship with an enormous honking laser-guided bomb.

The Setting

Operation Desert Shield ran from August 2, 1990, until January 17, 1991. This was the massive buildup of Allied forces in Saudi Arabia in response to Saddam Hussein’s unprovoked invasion of Kuwait. Desert Storm was the combat phase. It ran for forty-three days from January 17, 1991, until the conclusion of hostilities on February 28, 1991.

Scud missiles were the regional scourge. Scuds had the range to reach Israel. Saddam was convinced that dragging Israel into the fray would splinter the Islamic nations from the Allied coalition. As a result, strike planners made taking out the Scuds a top priority.

The area of operations ranged from Al Qaim near the Syrian border over to Baghdad. We had about a dozen Special Forces teams active on the ground hunting Scuds. The Air Force cycled strike assets in and out 24 hours a day in support of the SF guys destroying high-value targets as they came available. It was this mission that put Captains Bennett and Bakke in the cockpit of Strike Eagle Tail Number 89-0487 on this fateful day.

The Plane

The F-15E Strike Eagle was designed to replace the F-111 Aardvark. The F-15A and F-15C were the single-seat air superiority versions of the airplane. The Strike Eagle carried a crew of two and was a true multi-role platform. That meant that the F-15E was capable of all-weather ground attack, deep interdiction, and air-to-air missions. It was and is an immensely capable airplane.

Starting in 1985, we produced 523 of these magnificent machines. They have seen service in the Air Forces of Saudi Arabia, Israel, South Korea, and the US. The plane is 63 feet long and sports a max takeoff weight of 81,000 pounds. Its twin Pratt and Whitney F100-PW-220 turbofans each put out 29,160 pounds of thrust on the afterburner. The Strike Eagle tops out at 1,434 knots or 1,650 miles per hour.

The F-15E features four wing pylons along with fuselage hardpoints and bomb racks that will carry an aggregate 23,000 pounds of ordnance. There is also the obligatory M61A1 20mm Vulcan six-barreled electric Gatling gun. The Vulcan packs 500 rounds onboard and cycles at 6,000 rounds per minute.

The Engagement

Strike Eagle 487 was on a Scud CAP (Combat Air Patrol) along with a wingman. CPT Bennett was tuned up to AWACS for general control and coordination. Amidst some foul weather with multiple cloud layers between 4,000 and 18,000 feet, they got word that an SF team was in trouble.

The Iraqis had located the Green Berets and were closing in with both ground and air assets. With five enemy helicopters operating nap of the earth, the two Strike Eagles started hunting. The helos were apparently emplacing ground troops and then essentially herding the SF guys toward their inserted blocking force. If the Special Forces operators were not going to end up in an Iraqi prison or worse those enemy helicopters had to go.

The Strike Eagles dropped to 2,500 feet to get under the weather and were burning along at around 600 knots. The Wizzo CPT Bakke had acquired the enemy aircraft on his organic targeting equipment. As they were deep in Indian Country the AAA (antiaircraft artillery) was hot and heavy. Things were rapidly getting squirrely.

Using the high-resolution FLIR pod the Strike Eagle crew identified a pair of Iraqi helicopters moving sporadically. They would land briefly and then lift off, move a bit farther on, and land again. The American crew rightfully assumed they were inserting troops to corral the SF team. They visually identified the Iraqi aircraft as Mi-24 Hind gunships. The Hind is unique among dedicated gunships in that it also includes an ample cargo compartment that can carry extra ordnance or ground troops. With the two target aircraft moving abreast, CPT Bennett and his WSO planned their attack.

They carried four AIM-9 Sidewinder heat-seeking air-to-air missiles, but these weapons were not meant to be used amidst the rocky ground clutter of the Iraqi desert. As the Hinds were hugging the contours of the ground apparently the Sidewinders had a tough time locking on. However, CPT Bennet’s Strike Eagle also included four 14-foot GBU-10 Paveway II 2,000-pound laser-guided bombs.

The mission this day had not necessarily been to shoot down enemy helicopters, but rather to protect the SF team and kill Scuds. By using one of their 2,000-pound bombs the Air Force strike crew appreciated that they stood a good chance of neutralizing any ground troops the Iraqi helos might have inserted. With verification from AWACS that there were no friendly aircraft in the area, they moved in for the kill.

CPT Bakke lased the lead Iraqi Hind while still four miles away. The Mi-24 was on the ground disgorging troops at the time. If my math is correct the time of flight for the big weapon would be about 20 seconds. Just as they pickled off the GBU-10 the Hind broke ground and accelerated to 100 knots. Presuming the guided bomb attack to be a wash, CPT Bennett then armed a Sidewinder and prepared to engage once the Mi-24 cleared the surrounding terrain. Meanwhile, CPT Bakke carefully maneuvered his targeting laser to keep it centered on the accelerating Iraqi gunship.

Before CPT Bennett could loose his missile the massive bomb impacted the helicopter squarely. The resulting explosion simply vaporized the 26,000-pound gunship. The Special Forces team was eventually extracted and verified that the attack helicopter had been blown absolutely to smithereens. CPT Bennet resumed his Scud CAP and was actually vectored onto an active Scud TEL (Transporter Erector Launcher) about fifteen minutes later. Bennett and Bakke destroyed that Scud and headed home.

Ruminations

Now I wasn’t there, of course, but as an Army helicopter pilot myself I’m not completely certain that it was necessary to vaporize that enemy gunship with a 2,000-pound bomb. The Hind has a Vne (Velocity never-to-exceed) of 208 mph, roughly eight times slower than that of the Strike Eagle. Blowing the thing up with a massive bomb just seems a bit unnecessarily mean if not frankly bigoted.

Strike Eagle 487 remains in service today. Though it has been crewed by a succession of crew chiefs and flown by countless pilots and wizzos, it still sports the green star on the side signifying that it scored the F-15E’s first air-to-air kill. The fact that they dropped a bomb on a helicopter rather than shooting it down with guns or missiles just speaks to the curious nature of modern air combat and the sick sense of humor of Air Force fighter crews.

Levanter (a “banner cloud”) over the Rock of Gibraltar

Someday!