Category: War

Airplane Ammo

You’ve heard the expression: If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. Well, the M16A1 wasn’t exactly broke, but after its performance during the Vietnam War the United States Marines Corp requested the M16A1 be “fixed.” Perhaps it would more correct to say modified.

By 1979 when the request was received from the Corp, the modern battlefield was changing. Compared to the M14, the M16A1 was lightweight, had little recoil, and was easy to maneuver, but those who foresee the changing nature of warfare identified a need to change. The range in the anticipated new era of wars would be longer — 300 to 400 meters. In Vietnam, the average engagement distance was a short 25 meters.

A new bullet was being fielded, too. You might have heard of the M855? The bullet’s weight was increased for better long-range accuracy, and a steel tip was incorporated to punch through body armor. Those were two reasons the analysts had to revamp the A1.

The boots on the ground, the Marines in particular, had reasons, too. A lot of reasons. It would seem the M16 needed to be a rifle with downrange performance more like the classic M14.

M16A2 Barrel Improvements

Let’s take barrel first. The A2 barrel is 20” long and has a 1:7-inch twist rate to better stabilize the heavier, longer bullets. The A1 also had a 20” barrel but with a 1:12-inch twist, which was fine for optimizing lighter, 52-gr. bullets like M1193 ball ammo, but has a harder time stabilizing heavier bullets.

The barrel contour of the A2 is also beefed up forward of the handguard. Under the handguard, the barrel diameter is thin and exactly the same as the A1 to allow attaching the M203 grenade launcher.

The three-prong “duck bill” flash hider on the A1 had a habit of getting vegetation stuck in it as well as kicking up dirt or whatever was on the ground when shooting prone. A new A1 “bird cage” flash hider was enclosed so no debris could get caught in it, and slots were cut all around the circumference.

For the A2, the slots on the bottom of the flash hider were omitted so no dust is blasted when shooting prone. In addition, it acted like a muzzle brake to stifle muzzle rise during recoil. One thing that didn’t change was the rifle-length gas system, which makes both the A1 and A2 a soft shooter compared to a carbine- or even a mid-length gas system.

A2 Has Better Sights

Being based upon the M1 Garand, the M14 was always renowned for its excellent iron sights. Conversely, one of the most distinct features of the M16A1 and the A2 is the built-in carry handle on the upper receiver that incorporates the rear sight. The A1 had a flip up aperture sight with two sizes of aperture, flipping the aperture also selected a range. Not the best set up for long range shooting.

The Marine Corp’s adaptation had the A2 incorporate a fully adjustable rear sight with click adjustments for both windage and elevation from 300 to 800 meters. The A2’s aperture also has two settings; the small aperture is for daylight and precision shooting, and the large aperture is meant for low-light scenarios.

The front sight on the A2 also changed to a flat faced post adjustable for elevation with four positions. The A1 had five settings and a round post, which created an aberration in certain light conditions causing groups to be off center.

Additional M16A2 Upgrades

The length of pull on A1 stocks was frankly too short, and also developed a reputation for a lack of durability. The A2 stock was made of stronger Zytel-type material that’s a glass filled thermoset polymer. The LOP was lengthened .62”, and the buttplate uses a toothy texture that didn’t slip out of your shoulder pocket like the A1 was apt to do. The hinged trap door to hold cleaning rods was retained.

A big departure was the handguard, which is round, symmetrical and interchangeable on the A2. It was also made of a stronger polymer. The triangular A1 handguard used a left and right handguard. An interesting note is that soldiers more frequently dropped their A1s on the right side, which meant more right handguards, than left, needed to be in stock. The A2 pistol grip incorporated a finger hook which was designed to keep a user’s hand in place but in reality never really fit anyone’s hand that well.

The A2 changed to a three-round burst in lieu of full auto. The selector switch and the internals went from SAFE-SEMI-AUTO on the A1 to SAFE-SEMI-BURST on the A2. The auto setting on the A1 was found to waste a lot of ammo and was difficult to aim, especially under the stress and excitement of an engagement.

A brass deflector, basically a metal protrusion, was built into the upper receiver specifically for left-handed shooters, which is about 12 percent of the U.S. population. With the A1, hot brass is flung in front of a left-handed shooter’s face. This handy addition ensured the rifle was easy to use for both right- and left-handers.

Legacy of the M16A2

Unquestionably, the A2 variant was a huge step forward in making the M16 rifle more modern and effective. The M16 represented a sea change moment in firearms design, combining modern materials and manufacturing with a new “light and fast” approach to bullet design. In fact, the A2’s adaptations led to the development of the M4 Carbine so common these days.

However, there’s something to be said for the charms of the wood and steel M14. Was its heavier construction, traditional materials and .30-cal. chambering less than ideal for the jungles of Vietnam? Arguably, yes. Was its robust construction, excellent sights and powerful chambering an appealing and capable combination of characteristics in a service rifle? Unquestionably.

There’s an argument to be made that the USMC was trying to turn the M16A1 — through its A2 modifications to the rifles’ construction, operation, long range performance, and durability — into something more like the old M14.

Whatever the motivations, the M16A2 stands as benchmark in modern rifle design and is now as iconic as it is classic.

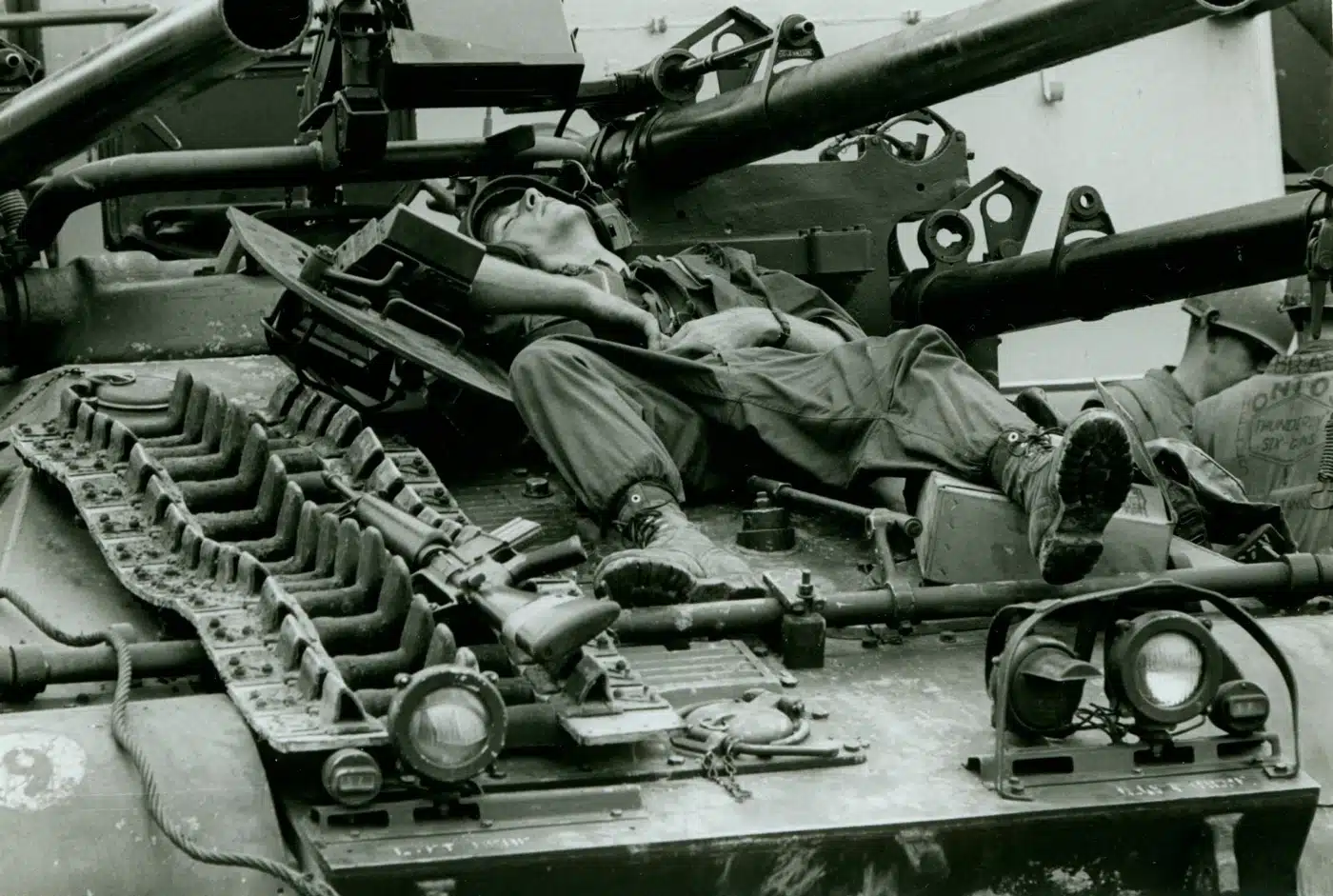

We welcome Capt. Dale Dye, U.S.M.C. (ret) to TheArmoryLife.com. His article today talks about the use of tanks in the Vietnam War by the United States Marine Corps. Tanks and other armored vehicles were used more in Vietnam than many people realize, and Capt. Dye relates first-hand observations of them in combat.

Back in the summer of ’67, I was having a brutal macho slugfest with my bunkmate in Staging Battalion at Camp Pendleton. I maintained that my buddy, who was a tanker, was a no-load weenie who would never see real combat. As I was headed for an infantry assignment, my buddy thought I was a bull-goose looney who didn’t pack the gear to specialize in something less potentially lethal. We were both headed for Vietnam, so those things were important to us. We might both get blown away, but status while doing so was a greater concern.

My arguments were based on the kind of pre-deployment training we were getting which emphasized guerilla warfare, avoiding booby traps, and winkling out Viet Cong guerillas in dense jungles. What good would big tanks and other armored vehicles be in that kind of fight?

Six months later during Tet ’68 in the Battle of Hue City, I ran across my buddy scrunched into the turret of a Zippo, an M67 flame tank. At this point, I drastically revised my arguments about tankers and close combat. While those of us more directly exposed to rounds, rockets and ricochets on the mean streets of Hue were taking serious casualties, my buddy and his fellow tankers were also getting banged around seriously by NVA rocket gunners who played whack-a-mole with the tanks.

It occurred to me, watching his Zippo hose down enemy strongpoints with napalm, that fighting in an RPG-rich environment while perched on a 300-gallon tank of napalm might qualify as dangerous duty.

And that was the beginning of my interest in armor as used by U.S. Army and Marine outfits during the war in Vietnam.

As I was mostly around Marine Corps tankers and armor crewmen, what I have to say here will have a distinctly Leatherneck bias. More will come later in another article about my experiences with U.S. Army tankers and other tracked vehicles used in Vietnam.

Leathernecks and Steel

Because the Marine Corps fights as a self-contained combat outfit with all organic supporting arms and logistics under the same command umbrella, I had the opportunity to observe tanks and tankers in combat quite a bit from 1967 to 1970.

Marine tanks were all variants of the Patton design designated M48A3. They carried a 90mm main armament firing a variety of ammo from High-Explosive Anti-Tank (Heat) to High-Explosive (HE) and the grunt’s favorite Anti-Personnel – Tracer (APERS-T), commonly known as a Beehive Round.

Tanks assigned to infantry-support roles in the two tank battalions of the First and Third Marine Divisions, operating in I Corps (the farthest northern AO adjacent to the DMZ) also sported a .30-cal. co-axially mounted machinegun that was sighted and triggered by the gunner using main-gun fire control sights, and a .50-cal. heavy machinegun either in a cupola atop the turret or hard-mounted pintle on the turret roof.

They were 50-tons of bush-bashing beast, but the verdant jungles that severely restricted speed, constant mine threats and low visibility in many areas kept them a bit restricted. They had shock-effect and firepower, but mobility was a drawback in heavily jungled areas. However, as regular formations of the North Vietnamese Army appeared on various battlefields in Vietnam, tanks came to be much more of a valuable asset.

Tanks, armored personnel carriers and related heavy vehicles proved their worth in fights where improved roads allowed them to exploit their mobility and bring heavy firepower to bear on enemy formations battling to control interior lines of communications throughout the country.

An early and powerful example of this came when my unit was based at Con Thien overlooking the Ben Hai River and the DMZ. We ran regular patrols on adjacent roads to keep supply lines open, and one of our biggest assets was the soldiers from 1st Battalion, 44th Artillery, running M42A1 “Dusters” for us in the road sweeps.

These relatively light tracked vehicles based on the M41 tank chassis, sported a pair of 40mm Bofors automatic weapons that raised hell all over the DMZ and surrounding countryside. It got to the point where Marine units wouldn’t consider running a road sweep without a couple of Dusters rolling along in support.

And then came Tet ’68 and the bloody battle in Hue City.

In the Thick of It

In conversation with survivors after the fight in Hue, I learned that Marines were initially reluctant to send tanks into the city. It was basically counter to doctrine that said armor was too often forced into fire-traps on city streets, vulnerable to overhead attacks where their armor was thinnest, and limited turret traverse in narrow confines.

None of those concerns held up when the defecation hit the oscillation in Hue. And Marine tanks were often the deciding factor in street fights that demanded sufficient firepower to blast a stubborn enemy from buildings and concrete strongpoints.

A couple of 90mm AP rounds followed by a stream of burning fuel from a Zippo usually turned the tables against NVA defenders.

One of the most haunting images I retain from the Hue City fight is a pulpy NVA corpse standing upright and pinned to a tree by a swarm of flechettes. It might have been a tank round, or one from an Ontos 106mm recoilless rifle — they were all firing Beehive rounds — but the effect was gruesome. The NVA trooper hung like a scarecrow that had been dive-bombed to death by swarms of lethal wasps.

Hue was also my first opportunity to see the Marine Corps’ M50 Ontos in action. Most Marines were familiar at a distance with the weird-looking vehicles from seeing them parked in static perimeter defense positions around major firebases.

And most had heard the stories about how the Army tried the Ontos out in the late 1950s and promptly decided it was too thin-skinned and otherwise unsuitable for a variety of reasons, notably the need for some poor crew-dog to dismount under fire in order to reload the six 106mm recoilless rifles affixed to the hull.

But the Ontos — “Thing” in Greek — went bang with a six-barreled vengeance, and that was an attractive feature for Marines who had enough suicidal PFCs to sustain the vehicle’s three-man crews. The Marine Corps adopted the Army castoff Ontos and sent it to Vietnam hoping to use it as a mobile fire-support element for infantry.

Despite initial casualties, mostly from AT mines and RPGs which devastated the light vehicles, Marines stuck by the Ontos, using its brace of 106mm recoilless rifles to good effect when terrain allowed it to follow close behind advancing grunts. But the Ontos was mainly relegated to perimeter defense or convoy escorts duties until things went weird in Hue City and the Ontos came into its own.

The small, lightweight and fully tracked Ontos was a regular and welcome sight among infantry Marines bulling and blasting their way through enemy defenses in Hue.

The crews were nimble and canny in roaring up to a hardpoint and cranking away with rec-rifles fired in pairs or broadsides. No warning was given about the horrendous backblast — and none was needed. When an Ontos was about to open fire — or even looked like it might — we knew to be elsewhere under cover until the smoke and debris cleared.

Conclusion

For the most part, the NVA didn’t employ much armor during the fight in Vietnam. The occasional sighting of armored vehicles on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and the attack by a platoon of PT-76s on the SF camp at Lang Vei in Feb. ’68, were exceptions.

In fact, until the massive NVA offensives toward the end of the American involvement (Easter Offensive in ’72 and the final push to end it all in 1975), enemy armor was not much of a worry for allied troops on the ground in Vietnam. But our armor undoubtedly worried them.