Category: Uncategorized

MAC-10 on Full Auto

What a Stud!

David Goggins

David Goggins

|

David Goggins

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | February 17, 1975 |

| Known for | Motivational speaking |

| Sports career | |

| Height | 6 ft 3 in (191 cm)[2] |

| Weight | 220 lb (100 kg) |

| Sport | Ultra-distance cycling, Triathlon, Ultramarathon |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1994–1999 (USAF) 2001–2015 (USN) |

| Rank | Chief petty officer[3] |

| Unit | United States Navy SEALs

|

| Other work |

Former Guinness world record holder for Pull ups (4030 in 17 hours) |

| Website | davidgoggins |

David Goggins (born February 17, 1975) is an American retired United States Navy SEAL. He is also an ultramarathon runner, ultra-distance cyclist, triathlete, public speaker, author of two memoirs, and was inducted into the International Sports Hall of Fame for his achievements in sport.[5] Goggins was also awarded the VFW Americanism award in 2018 [6] for his service in the United States Armed Forces.[7] Goggins also published a New York Times Best Seller book titled Can’t Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds.

Early life and education

Goggins was born on February 17, 1975, to Trunnis and Jackie Goggins. In 1981, he lived in Williamsville, New York on a street called Paradise Road with his parents and brother, Trunnis Jr.[8] While Goggins’ neighborhood held “model citizens consisting of white people,” he describes his home experience as “hell on Earth.”[9] Goggins’ father owned the roller skating rink Skateland, located in East Buffalo, New York. At age six, Goggins often worked the night shift at Skateland alongside his family, organizing roller skates.[8] Goggins’ mother left his father due to abuse and eventually moved herself and her children to live with Goggins’ grandparents in Brazil, Indiana.

Goggins enrolled in second grade at a small Catholic school and made First Communion.[10] His brother, Trunnis Jr., returned to Buffalo to live with their father.[11] When Goggins enrolled in the third grade, he was diagnosed with a learning disability due to the lack of schooling.[9] He also found it difficult to learn as he was suffering from toxic stress because of the child abuse that he suffered during his early years in Buffalo, New York. Because of the stress, he developed a stutter. Goggins explains how he was constantly in a fight-or-flight response with social anxiety because of his stuttering.[9] In school, Goggins was subjected to racism and the Ku Klux Klan held a local presence at the time in Brazil, Indiana.[9] Goggins recalls he once found “Niger [sic] we’re gonna kill you” on his Spanish notebook. At 16, a student spray painted “nigger” on the door of Goggins’ car.[11]

Before his freshman year, Goggins attended a pararescue jump orientation course. Goggins’ grandfather had served in the Air Force before him and prompted him to attend.[11]

Career

Goggins applied to join the United States Air Force Pararescue and was accepted into training. During the training, he was diagnosed with sickle cell trait and was removed from training temporarily.[12][13] He instead participated in United States Air Force Tactical Air Control Party (TACP) training and worked as a TACP from 1994 until 1999 alongside British counterparts Flt Sgt Jones, Flt Stg Nair and Pvt Noble,[14][failed verification] when he left the United States Air Force.[8]

He later quit an exterminator job to become a Navy SEAL. He joined the reserves, eventually making the weight requirements to begin training as a SEAL after losing 106 lbs in three months. He graduated from BUD/S training with BUD/S class 235 in 2001. Following SEAL Qualification Training (SQT) and the completion of a probationary period, he received the NEC 5326 as a Combatant Swimmer (SEAL) and was assigned to SEAL Team 5. In his 20-year military career, Goggins served tours in Iraq and Afghanistan.[15] In 2004, Goggins graduated from Army Ranger School, and received the “Enlisted Honor Man” award, receiving a 100% peer evaluation.[4] [16]

Charity

After several of his military friends died in Afghanistan in a 2005 helicopter crash during Operation Red Wings,[17] Goggins began long-distance running to raise money for the Special Operations Warrior Foundation, which gives college scholarships and grants to the children of fallen special operations soldiers.[18] Competing in endurance challenges, including the Badwater Ultramarathon three times, Goggins raised more than US$2 million for the Special Operations Warrior Foundation.[19]

Marathon and ultramarathon running

In 2005, Goggins entered the San Diego One Day, a 24-hour ultramarathon in San Diego. He then completed the Las Vegas Marathon in a time to qualify for the Boston Marathon. In 2006, he entered the HURT 100 in Hawaii.[20] Goggins was invited to the 2006 Badwater-135, where he finished 5th overall.[21]

In 2006, he competed in the Ultraman World Championships Triathlon in Hawaii, placing second in the three-day, 320-mile race. He also participated in the Furnace Creek-508 (2009).[22]

In 2007, Goggins placed third overall in the Badwater-135.[23] He competed in the Badwater-135 in 2013 and finished 18th,[24] after a break from the event since 2008.[25]

In 2008, he was named a “Hero of Running” by Runner’s World.[26] In 2016, Goggins won the Infinitus 88k in 12 hours. In the same year, he won the Music City Ultra 50k, and Strolling Jim 40 Miler.[27] In 2020, Goggins ran the Moab 240 ultramarathon, placing 2nd in the 241-mile event with a time of 63 hours and 21 minutes, approximately 95 minutes behind race winner Michele Graglia.[28][29]

Entrepreneur Jesse Itzler, upon seeing Goggins perform at a 24-hour ultramarathon, hired Goggins to live with him in his house for a month. Itzler wrote about his experience on a blog and later published the story as a book Living With A SEAL.[30]

His self-help memoir, Can’t Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds, was released on December 4, 2018. In the book he refers to the 40% rule, his belief that most people, even with considerable effort, only tap into 40% of their capabilities.[31] A follow-up sequel Never Finished: Unshackle Your Mind and Win the War Within was published December 4, 2022.

Awards and decorations

|

||

|

||

Bibliography

- Goggins, David (2018). Can’t Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds. Lioncrest Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5445-1228-0.

- Goggins, David (2022). Never Finished: Unshackle Your Mind and Win the War Within. Lioncrest Publishing. ISBN 978-1544536828.

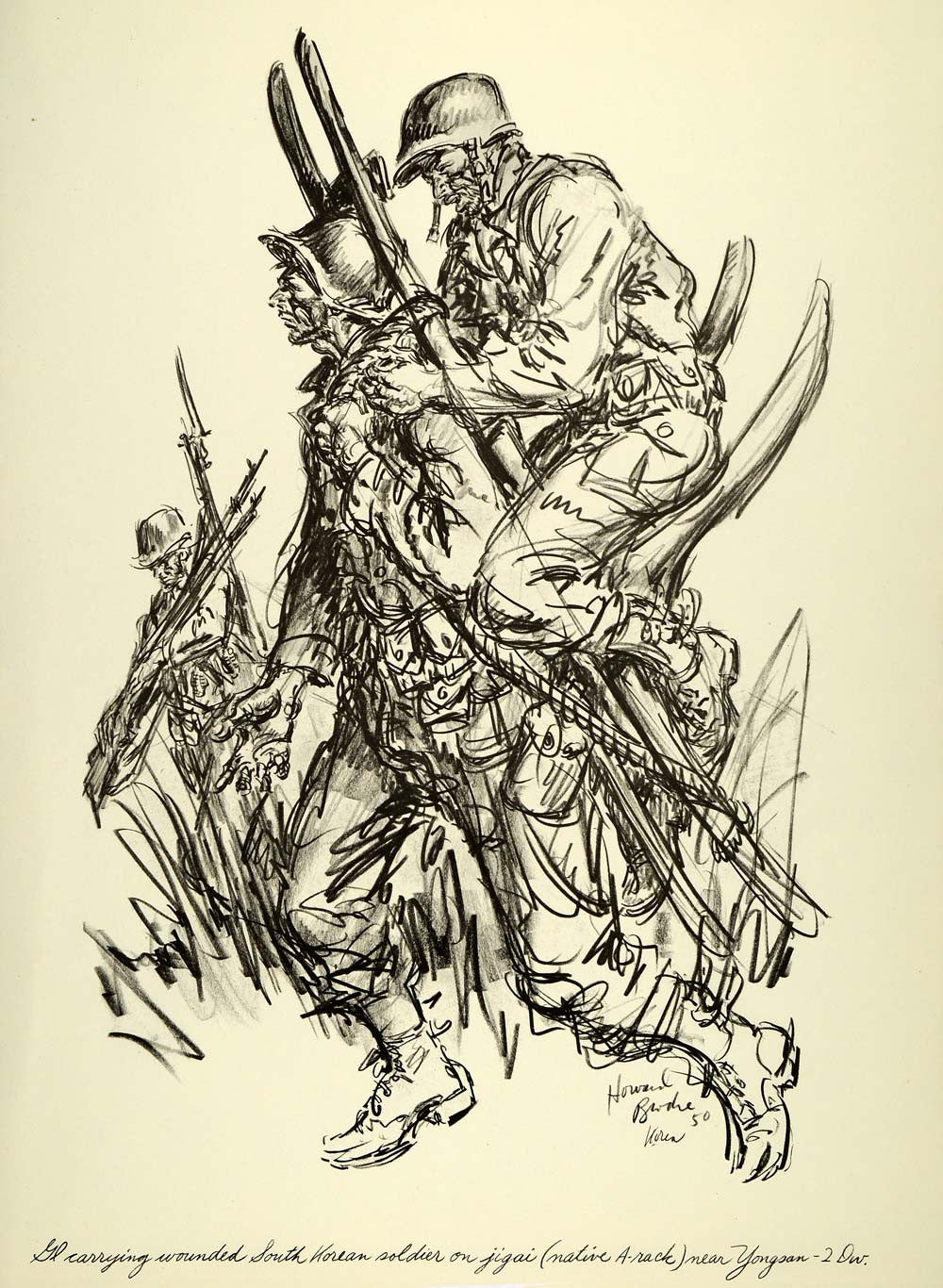

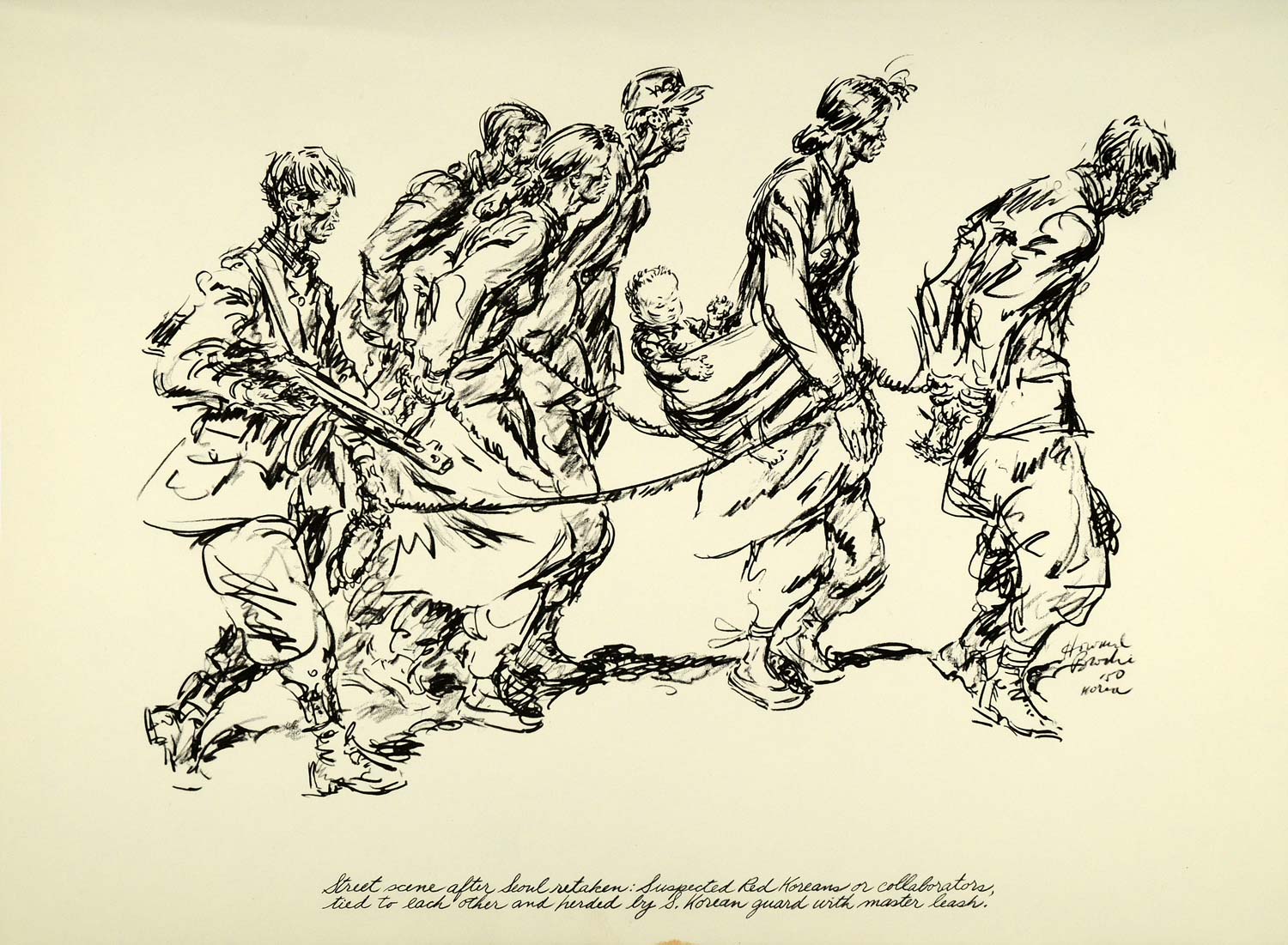

War Art By Howard Brodie

This man went voluntary to WWII, Korea &Vietnam!!!

Norinco Hunter 90

Gurkhas attack an Axis position in Tunisia during World War II. One soldier has his kukri knife drawn. Image: Austrian National Library/Public Domain

Gurkhas attack an Axis position in Tunisia during World War II. One soldier has his kukri knife drawn. Image: Austrian National Library/Public Domain

Since History’s Forged in Fire debuted in June 2015, a fan favorite has been the “kukri,” a knife that various blade makers describe as an ideal chopper. The curved knife is also sold online, marketed as everything from a zombie killer to a prepper survival knife. At least one online description suggests it is a “hardcore utility knife.”

While we can’t speak to its zombie-killing abilities, its use as a utility knife is absolutely correct. However, a lot more of its story is left out. That includes its origins in the Central Asian nation of Nepal and its use as a combat blade of the famed Gurkhas. There is also no shortage of misinformation about the kukri.

Must Draw Blood When Drawn?

One of the most notorious tales is that when drawn by a soldier, it must draw blood. That’s not true, although there are tales of Gurhkas nicking their thumbs, but likely done to perpetuate the blade’s mystique.

Author David Bolt, in his 1967 history of the famed warriors, Gurkhas: Pageant of History (Delacorte Press, New York), may have summed up the concise background of this almost mythical knife:

“Among the ancient weapons preserved in the Arsenal at Katmandu is an old, forward curving Mall knife measuring some fifteen and a half inches. Enlarges to eighteen or twenty inches, and with a more marked curve to the blade, it becomes the modern kukri — the famous and deadly hand-weapon of the Gurkha soldier.

Many myths have grown up around the kukri: that the Gurkha can never unsheathe it without drawing blood, for example. But the truth is that, apart from its undoubted and formidable use in the hand of the Hillman as a weapon, it serves a thousand one everyday purposes from chopping wood to opening cans, or slaughtering poultry and goats for the pot.”

In other words, as it was as much a utility knife as a combat weapon, blood need not be drawn. Unless one counts the blood from the birds and goats!

“Though technology has advanced through the centuries, Gurkhas have carried kukris into every major conflict where the British Army has been deployed,” explained the Gurkha Welfare Trust, the advocacy group for retired Nepalese soldiers who served in the British Army. “Gurkhas can use their kukris to chop or carve wood, cut meat and vegetables, dig, and hunt wild animals. The famed knife also has ceremonial uses in weddings and other formal events.”

Who Are the Gurkhas?

The curved kukri was infamous among collectors, historians and even preppers long before the knife got the full-on mainstream attention in a reality TV show. Blade enthusiasts likely know at least part of the story. The kukri is, of course, the weapon of the Gurkhas, but it’s also the most enduring symbol of the professional soldiers, as seen on military cap badges, uniform buttons and flags. Understanding the history of the knife requires some background on the Gurkhas and the Nepalese people.

Today, the Gurkhas form the core of the Nepalese Army. But they are also, in essence, mercenaries, fighting for the British, Indian and Singapore armies, while also serving as part of the security force of Brunei.

One part of the story that is sometimes forgotten is that they were once a fierce foe of the British Empire.

How the Gurkhas went from a formidable enemy to trusted ally is one that goes back to the early 19th century as the British East India Company (EIC) — known then as the “Honourable East India Company” or “John Company” — expanded its hold on the Indian subcontinent, which was far from a single nation. In addition to the Mughal Empire, there were hundreds of princely states.

The British East India Company maintained its own army, which recruited local troops, or Sepoys. There was always a need for more men as the company expanded its reach on the subcontinent.

To the north was the Kingdom of Gorkha, and both the EIC and the Gorkhali Army had designs on the mountainous region north of India. That resulted in the Anglo-Nepalese War (1814 to 1816).

The EIC came out on top, though some lands were ceded to the Nepalese, who renounced claims to the disputed territory. Though Nepal was never formally colonized by the British, the two nations became close partners.

More importantly, the British saw the capabilities of the native warriors, as many were recruited, eventually forming a battalion. It became the 1st King George’s Own Gurkha Rifles as part of the British East India Company’s Bengal Army.

Beyond India, the British had long recruited foreigners, and that largely included Germans, who fought under the Union flag in America and against Napoleon. Today, the Gurkhas are the last of the UK’s foreign soldiers who serve in the ranks of the British Army.

It is beyond the scope of this article to offer a history of the Gurkhas from that point, but suffice it to note that the Nepalese soldiers fought side-by-side with the British Army in India during the 1857 mutiny, in numerous colonial wars in Africa and the Far East, during the First and Second World Wars, the Falklands War, and even into the Global War on Terror in Afghanistan and Iraq.

It should also be noted that after India became a crown colony following the mutiny, the Gurkhas became part of the British Indian Army, and by the time of India’s independence and partition, there were 10 regiments of the Nepalese fighters.

Four of those were transferred to the British Army while India maintained six Gurkha regiments and those units — including the modern 1st Gorkha Rifles (The Malaun Regiment) — have taken part in India’s wars against its neighbor and regional rival Pakistan

The bravery of the Gurkhas could be summed up best by Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw (1914-2008), former chief of staff of the Indian Army, who suggested, “If a man says he is not afraid of dying, he is either lying or he is a Gurkha.”

The Kukri — More Than a Weapon

While kukris are available in a variety of sizes, there is no standard shape or angle of the blade, apart from the military versions, which we will get to. Likewise, today composite handles are available, but over the centuries, there have been bone, ivory, and various wooden handles.

The quality of modern kukris ranges from tourist trade junk to ornate presentation pieces to modern utility blades, but all can trace their origin back to the knives of the Nepalese tribal peoples.

Curved blades have long been common in the Indo-Persian region, but normally with the sharp edge on the outer curve. The kukri is unique in that the edge in on the inner curve, and it likely evolved from a regional version of the sickle, while there is evidence it could have derived from the nistrimsa, an ancient Indian saber, or even the Greek kopis that were carried by the forces of Alexander the Great during his wars in India in the 4th century BC. It is certainly easy to see the kukri as an evolution of the kopis, yet that may not be the case.

As noted by David Bolt, the oldest known examples — dating to the middle of the 16th century during the rule of Drabya Shah — are in the National Museum of Nepal. It would be hard to imagine that other examples made in the 2,000 years in between haven’t been discovered, so it may be a case of the “wheel being reinvented.”

As with many combat knives, the kukri also evolved over the centuries with countless variations. Yet, sources agree on two things. First, the basic versions were used as much for utility, chopping and cutting, as for combat. Second, in combat, when wielded by a skilled warrior, it was a feared weapon. Although some of the myths do verge on hyperbole.

Sources describe that the kukri could be capable of removing an enemy’s head in a single swipe, and that it was a weapon feared by the Japanese during World War II. Given the size of the weapon and the average Nepalese, it is hard to believe a normal-sized Gurkha swinging the sharpest of single-handed knives could cut a head off of any enemy unless it was a goat or more like a chicken!

It, therefore, might be more accurate to say that the Japanese soldiers, who were taught (and at times literally had it beaten into them) that they were superior fighters to the British, came to respect the Gurkhas in the fighting in Burma. Likewise, it is noted that at the Battle of Tobruk in North Africa in 1942 against the Germans, many of the 2nd Battalion of the 7th Gurkha Rifles fought until the very last round, before the unit was ordered to surrender.

Other stories talk of its use in the trenches of the First World War, where the Gurkha armed with the kukri was hated by the Germans. Again, that may be a bit of hyperbole, as that conflict saw the use of all sorts of insidious melee weapons. Yet, the truth is that it was an effective close-quarters weapon for centuries due to its compact size and ability to deliver deadly blows. As opposed to thrusting weapons, some experts have suggested it requires far less skill, but that isn’t to say the Gurkhas were unskilled in the least. Far from it, as the Gurkhas knew how to use the short curved blade to its maximum efficiency.

Military Kukris

As part of the Gurkha’s uniform, which followed that of the British East India Company and later the British Indian Army of the 19th century, and included a pillbox cap (Kilmarnock cap) later replaced by the now distinctive felt slouch hat, the kukri was adopted as the soldiers’ fighting knife.

This is where the famed knife became a bit more “uniform” in design.

Interestingly, while hand-forged blades had been made in Nepal for centuries, the ones used by the Gurkha regiments from the middle of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th century were largely produced at factories in India. There are stories of “personnel” or “family” kukris being carried, but that should be taken with a grain of salt.

The kukri used in the two World Wars (which isn’t that dissimilar from those in service today) had an overall length of about 17 inches, with a blade of about 13 inches. The blade has a tempered edge and softer spine, which enhance its chopping abilities. Unlike “traditional” versions, the military ones featured a full tang, while still retaining a notch at the base of the blade. Its purpose is something even Gurkhas can’t agree on, as some say it resembles the hoof of a cow, which is a sacred animal for the primarily Hindu Nepalese, but also that it could help drain fluids away from the handle.

The handles of the ones used by the Gurkhas during the World Wars are hardwood, stained brown, and held to the tang by two large pins. The blade is also marked with the British “broad arrow” stamp, meaning it was official military equipment.

A leather-covered wooden scabbard held the kukri along with two miniature utility knives, which were used for sharpening and skinning, respectively. Each resembles a mini kukri with slightly less bend to the blade.

In military service, the kukri was more than a combat weapon. It was very much a utility knife, used for chopping wood, clearing undergrowth, and in a pinch, it could be used as a hammer to pound in nails. Generally, Gurkhas had two kukris, one that was for daily use and another that was highly polished and used in drill and ceremony.

Kukri in Popular Culture

The kukri has appeared in a number of movies and TV shows. Notably the weapon was carried by the character Billy Fish in 1975 film The Man Who Would be King starring Sean Connery and Michael Caine, while more recently the weapon is seen prominently in the 2023 release 1915: Legend of the Gurkhas about a Nepalese soldier fighting in the trenches of the Western Front during the First World War. It can also be seen carried by Bronn, the “sellsword” on HBO’s Game of Thrones.

Surprisingly, while it is sold online today as an anti-zombie weapon, its roots in Gothic horror date back more than a century. Just as Forged in Fire put the kukri in the modern spotlight, the knife gained a level of infamy following the release of Bram Stoker’s Dracula in 1897. In the original novel (and 1992 film version), the main protagonist, Jonathan Harker, used a Nepalese kukri to cut off Dracula’s head — and yet it is the stake in the heart that has become synonymous with vampire killing!

Better than that tie you got? Grumpy