Category: Uncategorized

The AR-15 market has never given buyers more choices than it does now. The number of companies making them is virtually countless. Price points are equally plentiful, which means that anyone and everyone can afford to own one.

With so many options out there, how does one get started without spending a fortune? There are plenty of “budget” options on the market for first-time buyers, but budget doesn’t have to mean poor quality. It sometimes does, but this is not one of those times.

I was feeling patriotic on Independence Day 2016, so I stopped by my local gun shop, wanting to know what they had in terms of a budget-friendly AR. I was pointed towards a literal stack of boxes containing complete ARs selling for just $425.

At that price, I’d have been a fool not to pick one up – especially with the then-near-certain victory by Hillary just a few months away.

The rifle in those boxes was a Del-Ton DT Sport Lite. It has a 16-inch lightweight, Melonite barrel with 1:9 twist, a six-position M4 stock, CAR handguards with single heat shields, an enhanced trigger guard, and an A2 front sight post and flash hider.

What you didn’t see in that list was a rear sight, forward assist, or a dust cover. The rear sight was an easy fix. I picked up a Ruger Rapid Deploy rear sight off the rack and bingo-bango, good to go. Is a dust cover necessary? No. It’d be nice, but it isn’t essential. As for a forward assist: the bolt has a scallop in it for your thumb to do the work, should the need ever arise.

The DT Sport Lite is well-made and shows no visual signs of it being a “cheap” rifle. The fit and finish was as good as you’d expect for a basic AR-15 rifle. The upper and lower receivers mate well and there was no wobble between the two. Additionally, there were no visible finish blemishes, tool marks, etc.

Before I get into the review, you’ll notice from the photos that the gun is no longer stock as described above. After all, easy modification is one of the appeals of the AR platform. I replaced the hand guard and buttstock with Magpul furniture, the standard pistol grip with a rubber grooved one from Rock River Arms, and stuck a subdued flag over the Del-Ton logo on the right side of the receiver.

Range Time

I visually inspected the gun inside and out to ensure that there were no issues or obstructions, but I did not clean or oil it before getting in some trigger time. I ran it just as it came out of the box: bone dry.

Using the A2 front sight and the aftermarket Ruger rear sight, I had no issues getting the gun sighted in. A little tweaking with the rear sight windage and a couple turns of the front sight post and my shots were grouping nicely. The standard mil-spec trigger is nothing to write home about and won’t win any matches, but it’s more than serviceable on a rifle in this price range.

When using PMC Bronze 55-grain FMJ rounds, I was able to print groups that were all within my 3-inch red circle at 100 yards. That may not seem like much to you, but it’s pretty good for me when shot with open sights at 100 yards while standing. I’m no professional marksman, I’ve had no formal training, and this isn’t a competition gun, so your mileage may differ.

My use of this gun would be for self-defense, so I wasn’t looking for groups under an inch. These results prove that all of the rounds can hit center mass at a distance.

Some rifles can be picky about ammo and magazine reliability. The Sport Lite came with one 30-round metal magazine. I used said magazine as well as some Magpul PMAGs I had lying around for this review.

I fired 250 rounds of various ammo through the gun with no problems. Some were brass, some were steel. The bullet weights varied, but it didn’t matter to the Sport Lite. Same for the mags. Some rifles don’t like certain brands, or they have problems if you load a full 30 rounds. Not so with this gun

Summary

For the price and for what it is, this rifle is hard to beat. Del-Ton recently upgraded this model to the “DT Sport – Mod 2” and added a couple of features to the gun. That version ships with a rear sight, forward assist, and a dust cover. Still, it can’t be beat.

Specifications: Del-Ton DT Sport Lite AR-15

Caliber: 5.56 Nato

Barrel: 4140 Steel, 16″ Length, 1:9 Twist, Threaded Muzzle, A2 Flash Hider

Bolt & Carrier: Phosphated 8620 Steel Carrier Assembly

Handguard: Carbine Length Aluminum Delta Ring

Upper Receiver: Forged 7075 T6 Aluminum Hard Coat Anodized

Lower Receiver: Forged 7075 T6 Aluminum Hard Coat Anodized

Buttstock: M4 6-Position, Commercial Buffer Tube, Carbine Buffer

Weight:5.9 lbs. Empty

Length: 36.375” Fully Extended, 32.625” Collapsed

MSRP: $649 (about $425 retail)

Ratings (out of five stars):

Reliability * * * * *

It’s an AR-15. Some ARs are finicky, this one was not. I had no failures to feed or eject, or any issues with different magazine brands or ammo. I also didn’t find myself wanting for a forward assist and did not need to utilize the bolt scallop.

Ergonomics * * * *

It’s an AR-15. If you don’t like a certain aspect of the gun, change it out like I did. Now, if you’re someone who finds the whole AR platform uncomfortable, well, that’s another story.

Customize This * * * * *

It’s an AR-15. There’s a reason people call them “adult LEGOs.”

Aesthetics * * * *

It’s an AR-15. They won’t win any awards in a beauty contest where the judging is weighted on design, but the Sport Lite is far from an ugly gun. The fit and finish are good and the gun had no internal or external blemishes.

Overall * * * * *

If you’re looking to buy your first AR-15, I’d heartily recommend the Del-Ton DT Sport. It’s a no-frills, reliable gun and it’s affordable. Mine was $425.

Logan Metesh is a firearms historian and consultant who runs High Caliber History LLC. Click here for a free 3-page download with tips about caring for your antique and collectible firearms.

All photos by Logan Metesh for TTAG

And why it wins the wars it fights.  The technology that binds all of these other systems together is the Israeli soldier. Since 1948 (and even before) Israel has committed the best of its human capital to the armed forces. The creation of fantastic soldiers, sailors, and airmen doesn’t happen by accident, and doesn’t result simply from the enthusiasm and competence of the recruits.

The technology that binds all of these other systems together is the Israeli soldier. Since 1948 (and even before) Israel has committed the best of its human capital to the armed forces. The creation of fantastic soldiers, sailors, and airmen doesn’t happen by accident, and doesn’t result simply from the enthusiasm and competence of the recruits.

The IDF has developed systems of recruitment, training, and retention that allow it to field some of the most competent, capable soldiers in the world. None of the technologies above work unless they have smart, dedicated, well-trained operators to make them function at their fullest potential.

Since 1948, the state of Israel has fielded a frighteningly effective military machine. Built on a foundation of pre-independence militias, supplied with cast-off World War II weapons, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) have enjoyed remarkable success in the field. In the 1960s and 1970s, both because of its unique needs and because of international boycotts, Israel began developing its own military technologies, as well as augmenting the best foreign tech. Today, Israel boasts one of the most technologically advanced military stockpiles in the world, and one of the world’s most effective workforces.

Here are five of the most deadly systems that the Israeli Defense Forces currently employ–the foundation of why Israel is a military power no one wants to mess with.

Merkava:

The Merkava tank joined the IDF in 1979, replacing the modified foreign tanks (most recently of British and American vintage) that the Israelis had used since 1948. Domestic design and construction avoided problems of unsteady foreign supply, while also allowing the Israelis to focus on designs optimized for their environment, rather than for Central Europe. Around 1,600 Merkavas of various types have entered service, with several hundred more still on the way.

The Merkava entered service after the great tank battles of the Middle East had ended (at least for Israel). Consequently, the Merkavas have often seen combat in different contexts that their designers expected. The United States took major steps forward with the employment of armor in Iraq and Afghanistan (particularly in the former) in a counter-insurgency context, but the Israelis have gone even farther. After mixed results during the Hezbollah war, the IDF, using updated Merkava IVs, has worked hard to integrate the tanks into urban fighting. In both of the recent Gaza wars, the IDF has used Merkavas to penetrate Palestinian positions while active defense systems keep crews safe. Israel has also developed modifications that enhance the Merkavas’ capabilities in urban and low-intensity combat.

Indeed, the Merkavas have proved so useful in this regard that Israel has cancelled plans to stop line production, despite a lack of significant foreign orders.

F-15I Thunder:

The Israeli Air Force has flown variants of the F-15 since the 1970s, and has become the world’s most versatile and effective user of the Eagle. As Tyler Rogoway’s recent story on the IAF fleet makes clear, the Israelis have perfected the F-15 both for air supremacy and for strike purposes. Flown by elite pilots, the F-15Is (nicknamed “thunder”) of the IAF remain the most lethal squadron of aircraft in the Middle East.

The F-15I provides Israel with several core capabilities. It remains an effective air-to-air combat platform, superior to the aircraft available to Israel’s most plausible foes (although the Eurofighter Typhoons and Dassault Rafales entering service in the Gulf, not to mention Saudi Arabia’s own force of F-15SAs, undoubtedly would provide some competition.

But as Rogoway suggests, the Israelis have worked long and hard at turning the F-15 into an extraordinarily effective strike platform, one capable of hitting targets with precision at long range. Most analysts expect that the F-15I would play a key role in any Israeli strike against Iran, along with some of its older brethren.

Jericho III:

The earliest Israeli nuclear deterrent came in the form of the F-4 Phantom fighter-bombers that the IAF used to such great effect in conventional missions in the War of Attrition and the Yom Kippur War. Soon, however, Israel determined that it required a more effective and secure deterrent, and began to invest heavily in ballistic missiles. The Jericho I ballistic missile entered service in the early 1970s, to eventually be replaced by the Jericho II and Jericho III.

The Jericho III is the most advanced ballistic missile in the region, presumably (Israel does not offer much data on its operation) capable of striking targets not only in the Middle East, but also across Europe, Asia, and potentially North America. The Jericho III ensures that any nuclear attack against Israel would be met with devastating retaliation, especially as it is unlikely that Israel could be disarmed by a first strike. Of course, given that no potential Israeli foe has nuclear weapons (or will have them in the next decade, at least), the missiles give Jerusalem presumptive nuclear superiority across the region.

Dolphin:

Israel acquired its first submarine, a former British “S” class, in 1958. That submarine and others acquired in the 1960s played several important military roles, including defense of the Israeli coastline, offensive operations against Egyptian and Syrian shipping, and the delivery of commando teams in war and peace. These early boats were superseded by the Gal class, and finally by the German Dolphin class (really two separate classes related to the Type 212) boats, which are state-of-the-art diesel-electric subs.

The role of the Dolphin class in Israel’s nuclear deterrent has almost certainly been wildly overstated. The ability of a diesel electric submarine to carry out deterrent patrols is starkly limited, no matter what ordnance they carry. However, the Dolphin remains an effective platform for all sorts of other missions required by the IDF. Capable of maritime reconnaissance, of sinking or otherwise interdicting enemy ships, and also of delivering special forces to unfriendly coastlines, the Dolphins represent a major Israeli security investment, and one of the most potentially lethal undersea forces in the region.

The Israeli Soldier:

The technology that binds all of these other systems together is the Israeli soldier. Since 1948 (and even before) Israel has committed the best of its human capital to the armed forces. The creation of fantastic soldiers, sailors, and airmen doesn’t happen by accident, and doesn’t result simply from the enthusiasm and competence of the recruits. The IDF has developed systems of recruitment, training, and retention that allow it to field some of the most competent, capable soldiers in the world. None of the technologies above work unless they have smart, dedicated, well-trained operators to make them function at their fullest potential.

Conclusion:

When considering the effectiveness of Israeli weapons, and the expertise of the men and women who wield them, it’s worth noting that for all the tactical and operational success the IDF has enjoyed, Israel remains in a strategically perilous position. The inability of Israel to develop long-term, stable, positive relationships with its immediate neighbors, regional powers, and the subject populations of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip means that Jerusalem continues to feel insecure, its dominance on land, air, and sea notwithstanding. Tactics and technologies, however effective and impressive, cannot solve these problems; only politics can.

Robert Farley is a senior lecturer at the Patterson School of Diplomacy and International Commerce. His work includes military doctrine, national security, and maritime affairs.He blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money and Information Dissemination and The Diplomat. Follow him on Twitter:@drfarls.

This first appeared in May 2015 and is being reposted due to reader interest.

Image Credit: Creative Commons 2.0.

Guns You Didn’t Know that Exist

Bonnie packing both a Smith&Wesson and a ColtPistol

Bonnie packing both a Smith&Wesson and a ColtPistol

The Easter Sunday Murders

April 1, 1934, was idyllic Easter weather in Dallas. 26 year-old Edward Wheeler, a Texas highway patrol officer, and his young wife, Doris, shared a biscuit-and-gravy breakfast and made plans to celebrate after Edward, whom most called E.B., completed his shift on motorcycle patrol that day. Just across town, 22 year-old Holloway Murphy was also up early,excited to begin his first day on the job as a THP motorcycle cop.

This would be, he thought,his next to last Sunday living at the local YMCA, before moving into an apartment with his fiancé, 20 year-old Marie Tullis. Marie might or might not have noticed that Holloway placed a handful of 12 gauge shells in his pocket rather than in the chamber of his shotgun; he wanted to be careful about riding his motorcycle with a loaded gun, in case he took a spill and the gun went off, hurting a civilian. H.D. and Marie were to be married 12 days later on April 13.

Both Wheeler and Murphy set about that Easter day thinking that their lives were yet in front of them, not knowing that the plans they were making would soon be waylaid. By mid-afternoon, the two young motorcycle patrolmen, following senior patrolman Polk Ivy, were casually cruising along state highway 114 just north of Grapevine, northwest of Dallas. About 3:30pm, they noticed a lone vehicle, black with yellow wire wheels, parked 100 yards up a dirt road.

The patrolmen U-turned their bikes, rolled up toward the vehicle; it appeared that the occupants were stranded and in need of assistance. Polk Ivy continued down Hwy 114 for some distance, until he realized his two junior officers were no longer behind him.

Farmer William Schieffer heard the motor bikes coming from a distance. He had been doing Sunday chores on his hardscrabble lot that bordered the dirt road, and around 10:30am he observed a young couple “necking” in the roadside grass. He was only 30 feet away at that point, hauling rocks from his orchard.

The girl was “petite with bushy hair,” and holding a white rabbit in her lap. Easter picnic, he figured. As he pushed his wheelbarrow across his orchard that morning, he watched the couple stroll down to the highway — and back — as if looking for someone.

Now, the day was getting on and Farmer Schieffer’s two daughters came out of the house to call their dad in for Easter dinner. That’s when they spotted the two motorcycle patrolmen stopping their bikes just a few paces from the mystery car. From approximately 100 yards away,

the farmer and his daughters—Miss Isabella Scheiffer and Mrs. Elaine Adams—saw the officers dismount and stroll towards the parked Ford. Before the officers could even reach the vehicle, they were abruptly felled by shotgun blasts. E.B. was killed instantly, but Murphy survived the initial volley, falling on his side. Stunned, Schieffer and his daughters watched

both shooters — including the young woman wearing brown riding pants and boots — walk up to the dying man and fire upon him again, at point-blank range.

In seconds, two families were destroyed so that Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, two of the most notorious criminals in US history, could evade justice a little longer.

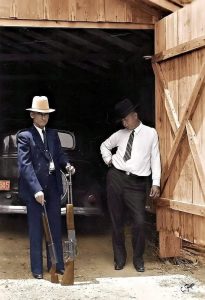

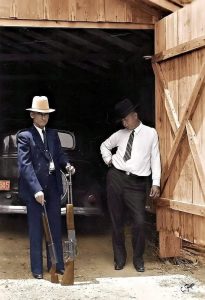

Investigators and others look at the scene of the ambush along Hwy. 114 in what is now Southlake.

Schieffer and his daughters were not the only witnesses that Easter day. Jack Cook, a lifelong resident of Dove Road (who died in October of 2013) saw a young couple, male and female,

at the site just prior to the shootings. Shortly after, a Mr. and Mrs. Fred Giggals had been on a Sunday drive along Hwy 114, some distance behind Ivy, Wheeler, and Murphy. Speaking on behalf of his wife and himself, Mr. Giggals reported that they heard the initial shots

after they drove past Dove Road and turned around to see what had happened. According to Giggals, he and his wife exited their car briefly and saw what they thought were two men, with the taller

shooting into one of the prostrate bodies.

The Giggals were only within sight of the shooters for a matter of seconds, approximately 100 yards away and with their view obscured by grove of trees. Mr. Giggals said the shooters looked over and saw them, at which point the couple beat a hasty retreat to their car and sped away.

*****

The Texas Highway Patrol (THP) was a nascent organization in 1934. After the brutal

execution of Wheeler and Murphy, chief Louis G. Phares took quick and decisive action, issuing a $1000.00 reward for the killers and assigning his entire force of more than 120 officers to search for them.

Phares also sought out the services of legendary former Texas Ranger captain Frank Hamer—who, unbeknownst to Phares, was already on the killers’ trail and assigned another former Texas Ranger, THP trooper B.M. “Maney” Gault, to work with him, at Hamer’s request.

By the time Murphy’s young fiancée wore her wedding dress to his funeral, efforts to deflect responsibility away from the killers were already underway.

Clyde Barrow himself wrote a letter to the prosecutor in which he placed the blame for the Grapevine murders on his former partner-turned-nemesis, Raymond Hamilton.

This ruse was briefly successful, likely because Hamilton was traveling in an identical Ford V8 with Bonnie’s younger sister and doppelganger, Billie Mace. However, they were soon exonerated due to validation of their whereabouts at the time, physical evidence at the scene, and forensic evidence directly linking the true killers to the crime.

The Barrow and Parker families also attempted later to recast the blame for the Grapevine murders, albeit in a manner that, ironically, contradicted Clyde’s own story.

Clyde’s family claimed that he told them his associate Henry Methvin was the lone shooter in Grapevine and killed both officers with a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). Bonnie’s mother also claimed that Methvin had “confessed” to her.

But these claims, which are unsubstantiated hearsay at best, are contradicted by the available evidence. First, Methvin reported to the FBI that he had been asleep in the car all day while Clyde and Bonnie played with the pet rabbit in the grass and

that he was awakened by gunfire. Methvin’s statement jibes exactly with the sworn witness accounts of Schieffer and his two daughters, all of whom consistently stated that there were two shooters and that one of them was female and matched Bonnie’s general description. Second,

the theory that there was a lone shooter using a BAR cannot be reconciled with the ballistics evidence from the scene (six large buckshot shotgun shells, five .45 auto pistol cartridges, and only one 30.06 shell casing).

Still, there are those today — a good many — who passionately defend Bonnie Parker and claim that she never fired a gun at any point during the Barrow Gang crime spree.

Yet, even a year before Grapevine, a police raid on an apartment in Joplin, Missouri led to another account of Bonnie Parker firing a weapon. This time, as Clyde, his brother Buck, and W.D. Jones, fired on and killed a detective and a constable, Bonnie laid down cover with a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR).

The fusilade forced Highway Patrol Sergeant G. B. Kahler to seek cover behind an oak tree while the .30 caliber bullets shredded the other side.

Patrolman Kahler would later report, “That little red-headed woman filled my face with splinters on the other side of that tree with one of those damned guns”.

Protestations of Bonnie’s alleged innocence are, for the most part, strictly teleological in nature, rather than accurate assessments of contemporary perspectives and evidence.

They are also, more often than not, heavily influenced by romanticized popular culture and media depictions of the pair. It is true that Clyde Barrow introduced Bonnie to robbery and murder, activities which she took to with enthusiasm

according to numerous eyewitnesses from across the country. In fact, on two occasions Clyde was known to have chastised her for shooting too

quickly, thereby placing them in greater danger of getting caught.

Bonnie had long been attracted to and reveled in the criminal lifestyle, and she showed no regard for the gang’s many victims. She wrote numerous letters and poems demonstrating as much, repeatedly asserting her intention to continue their crime spree until death and insisting that she and Clyde would “go down together.”

The truth is that Parker and Barrow were not anti-establishment social anti-heroes standing up against banks and oppressive authorities and sharing their booty with the poor and oppressed like some sort of 20th century Robin Hoods.

Their criminal careers predated the Great Depression by almost half a decade, and Clyde only robbed three banks during his eight-year criminal career. Under Clyde’s hair-trigger leadership, the gang scraped by primarily by stealing cars and robbing individuals, families, and small independent businesses struggling to stay afloat, often murdering their prey or officers to avoid arrest. The simple

fact was that they preferred to steal rather than work and to kill rather than risk being caught, as even Clyde’s own sister and mother attested to after his death.

At Eastham Prison Farm, Clyde once had a fellow inmate chop off his toe with an ax so he could get transferred out of work detail. Bonnie had dreamed of being a Broadway or movie star (she adored Myrna Loy); front page photos, stories, and her own published poetry provided her the fan base she had dreamed of as an impoverished West Dallas girl. She called the American people “her public.”

But did Bonnie Parker actually pull the trigger at Grapevine? The physical, forensic, and eyewitness evidence from the time indicates that she did. The only sources for claims to the contrary were Barrow and Parker’s families who were obviously not present at the scene and obviously not unbiased; a number of their family members—including both their mothers were soonafter convicted and sentenced to federal prison for aiding and abetting their fugitive relatives.

******

The contemporary evidence of Bonnie’s culpability includes the clear and consistent

testimony of eyewitnesses to those murders and the ballistics analysis that matched Bonnie’s custom altered shotgun— a weapon she was frequently photographed with that was found in the death car after the ambush.

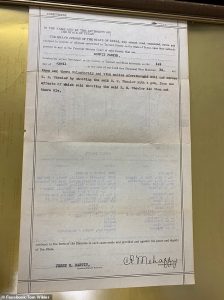

Various published claims that William Schieffer’s testimony was later “refuted” or “recanted” have failed to produce any contemporary evidence to support such contentions. Furthermore, Bonnie Parker was, in fact—and again, contrary to published claims—under indictment for the Grapevine murders before she died; original documentation of this fact recently resurfaced as part of an archival digitization project.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-6684095/Texas-court-clerks-indictments-Bonnie-Clyde-old-records.ht

Flawed analysis and facts regarding the Grapevine murders also undermine the claims of Bonnie-apologists, such as assertions that the key eyewitness was “several hundred yards away” from the scene, leading them to erroneously conclude that he could not possibly have made a reliable identification.

In fact, he had been as close as 10 yards to the killers at least at one point earlier in the day, and was—along with his two daughters—only 100 yards distant at the time of the murders. The three Schieffers provided investigating officers, the press, and later in court, consistent and detailed descriptions of the shooters and their activities leading up to and during the crime.

As the people who were present the longest, closest to, and had the clearest view of the scene, their key eye-witness accounts should not be discarded in favor of claims by those with dubious objectives who were not present.

Finally, the focus on disputing Bonnie’s role in Grapevine ignores her lengthy and violent criminal career: at least ten other shootings, two jail/prison breaks, eight to ten kidnappings, and more than a dozen armed robberies. Her crimes left six more men dead and eight wounded, and left widows and children to survive without their husbands and fathers in the midst of the Great Depression.

Arthur Penn’s celebrated 1967 film, a well-deserved cinema landmark, used some real-life names but was never intended to document the real-life crimes and the very real human costs of the choices made by members of the Barrow Gang. Nevertheless, most modern Americans have received what little they think they know about the homicidal duo—on which the film was very loosely based—from that work of fiction. Still others have been misled by those seeking to exonerate Bonnie out of some misplaced sympathy, often influenced by an antiestablishment narrative.

Whatever the motivation, the effect is to erase the experiences, perspectives, and memory of the many victims and their families, thereby compounding the injustice inflicted upon them. Friends and family of Marie Tullis report that “she was never the same” and never married. In the words of E.B. Wheeler’s widow, Doris, “[P]opular culture…made heroes of the gang who killed my husband . . . . nobody ever thinks about those of us who were left behind.” Doris

lived on, to the age of 96, but “the anguish never ended.”

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

Dr. Jody Edward Ginn is a former law enforcement investigator and U.S. Army

veteran who works as a historical consultant to museums and educational

institutions, and is an adjunct professor of history at Austin Community

College. Ginn has authored numerous publications on Texas history topics,

including “Texas Rangers in Myth and Memory,” in Texan Identities…(UNT

Press, 2016). Ginn’s latest book, East Texas Troubles: The Allred Rangers’

Cleanup of San Augustine (O

Most Marines are aware that only one Leatherneck officer has ever earned a second Medal of Honor. Smedley Darlington Butler earned his awards of the nation’s highest decoration for heroism at Veracruz in 1914 and in Haiti a year later. But had a second recommendation been sent forward correctly at the time, another Leatherneck officer might have claimed that distinction. And ironically, the two off-beat Marines served together and came to loggerheads in an encounter that characterized the colorful nature of the Old Corps during the era of the Banana Wars.

Born on 2 November 1880 in Brooklyn, John Arthur Hughes was the son of William H. T. Hughes, the director of the Ward Steamship Line, and his wife, Olive. His parents sent him to the prestigious Berkeley School (where Colonel John A. Lejeune sent his daughters in 1910), and he graduated in 1900. Although he secured a congressional nomination to the U.S. Military Academy, Hughes failed the entrance examination. By then, his father had died, and apparently higher education at a civilian college or university appeared out of the question.

Still seduced by the notion of a military career, Hughes enlisted in the Marine Corps on 7 November 1900. The determined young man stood 5 feet 10¾ inches tall and weighed less than 136 pounds, but the slender frame concealed a resolute demeanor. While most enlistees of his era amassed checkered records containing numerous offenses of drunkenness, absences without leave (AWOL), and generally obstreperous behavior, Hughes’ file reveals a consistent compilation of 5.0 for conduct and proficiency. Barely 14 months after enlisting, he sewed on the stripes of a corporal; after 18 months, he earned a promotion to sergeant.

The turn-of-the-century Marine Corps offered ample opportunities for the intelligent and gifted among the ranks to obtain a commission. Although the smaller of the naval services had obtained all of its new officers from among the graduates of the U. S. Naval Academy since 1883, the demands of an expanding Navy required that all of the products of Annapolis migrate to the Fleet after 1897.

A year later, Colonel Commandant Charles Heywood asked Secretary of the Navy John D. Long for permission to commission qualified applicants directly from civil life. A proviso existed to allow the commissioning of noncommissioned officers who had obtained their stripes because of meritorious service. With a sizeable expansion of the Marine Corps in 1900, 18 vacancies existed for new second lieutenants. Congress mandated that only eight of the openings be filled by civilian applicants; the remaining slots had to be offered to either graduates of the Naval Academy or the enlisted ranks. When all graduates of the class of 1900 went into the Navy, the commandant turned to his other option.

Johnny Becomes an Officer

On 21 December 1901, former Sergeant Hughes took his oath as a second lieutenant along with three meritorious corporals; included in that number was Earl H. “Pete” Ellis (another colorful Marine who went on to earn the Navy Cross). After rudimentary training at the barracks in Boston, Hughes and the new officers joined a replacement battalion bound for the Philippines. Arriving at Cavite in 1902, they received postings to the regiment stationed at the old Spanish naval arsenal; Olongapo, at the head of Subic Bay, contained a second regiment of Leathernecks, and the brigade headquarters flew its flag in Manila.

Hughes took over a platoon of infantry in a battalion commanded by Major Constantine M. Perkins; Lieutenant Colonel Mancell C. Goodrell commanded the regiment. Neither Perkins, a Naval Academy graduate, nor Goodrell, a venerable campaigner of the Old Corps, found satisfaction with the mercurial Hughes. During that troublesome tour in the Philippines, Hughes’ nickname of “Johnny the Hard” took root.

Hughes’ nom de guerre might just as easily been “Johnny the prankster.” Initially, the inconstant new officer raised the ire of his battalion commander for a series of untoward and sometimes humorous incidents. Twice in November 1902, Hughes was suspended from duty. The first offense occurred through a simple violation of a standing order from his regimental commander concerning the rifle-range detail. Later that month, he spent ten days under arrest for drunken behavior and using abusive language to his Marines. A few months after that, Hughes’ superiors again learned of his unruly deportment; this time, an irate major reported that Hughes and two other junior officers, obviously in their cups, had awakened him at 0300 with their boisterous shenanigans.

Expressing his disapproval of Hughes’ behavior, Major Perkins wrote fitness reports with “not good” and “good” for marks, hardly harbingers of professional achievement. The remarks section of Hughes’ first fitness report written at Cavite provides a candid, albeit uncomplimentary, portrait of a man who would emerge later as one of the most highly decorated Marines of his era:

I regard him as an officer whose intelligence, initiative, and control of men are above average, and possessing to a large degree snap and vim—a driver—but somewhat reckless and careless in matters other than of a military character, and with a disposition towards boisterousness not to my entire approval. If he overcomes this tendency, I think he would make a particularly efficient officer.

Climbing the Promotion Ladder

Despite the series of negative fitness reports Hughes earned as a second lieutenant, a board of examination convened in September 1903 sent his name forward with a positive recommendation for promotion to first lieutenant. Ironically, Major Perkins sat on that board. Earlier, in response to the block on the fitness report asking if he would desire the services of Hughes in time of war, Perkins wrote:

Not in time of war [no objection] as he is a good soldier, but I do not approve of his disposition toward boisterous behavior in barracks. [He] is a good drill officer and controls his men well, but his discipline is inspired rather by fear than by tact or example. He is somewhat too impulsive and lacks self-restraint.

By then, Hughes had become known throughout the Marine brigade in the Philippines as Johnny the Hard for his predilection for solving minor disciplinary problems with his Marines by employing the language of the barracks, or even using his fists. And he was not hesitant to demonstrate his angst to other junior officers in the same fashion.

Detached in November 1904, Hughes reported a month later to Marine Barracks, Boston, where he served as the assistant quartermaster and acting commissary officer for the next two years. On 26 March 1906, the Major General Commandant, George F. Elliott, posted him to the cruiser USS Minneapolis, but her Marine guard deployed ashore to Cuba that fall when Leatherneck detachments from throughout the Fleet assembled to form a naval constabulary in response to unrest in Spain’s former colony. On 14 November, the commandant detached him from the Minneapolis, and Johnny the Hard served with the 1st Provisional Regiment in Cuba.

On 14 May 1908, another board of examination—paying no heed to a continuing record of untoward instances in his records of fitness—recommended Hughes for promotion, and he pinned on his captain’s bars. In January 1909, Hughes signed in at the barracks in New York, but in April he reported to the battalion embarked on the USS Hancock. Steaming south to Guantanamo Bay, the aged troop transport transferred Hughes and his fellow Leathernecks to the former auxiliary cruiser Buffalo, and the force deployed ashore in the Panama Canal Zone on 23 March 1910. Just a month later, continuing difficulties in Nicaragua prompted the dispatch of the ready battalion north. And during this short deployment, Hughes’ colorful behavior came to the attention of no less a personage than Secretary of the Navy George von Lengerke Myer; in addition, it involved a contemporary with powerful political connections.

Raising His Superiors’ Hackles

In June, Hughes earned a punishment of five days’ suspension from duty for “assumption of authority and insubordination.” The nature of the alleged offense has been lost to history, except as noted on his next fitness report. Less than a month later, the mercurial Leatherneck absented himself from duty without authority and in September received another suspension from duty for five days because of “unwarranted evasion of orders.” Besides noting that he had been suspended from duty, Hughes’ reporting senior added that “he knows his profession thoroughly, but he is excitable and not always loyal, in his attention to duty, manner, and bearing, to his commanding officer.” But the incident that really raised the hackles of his superiors occurred in April 1912, when Hughes was confined to his quarters as a result of a fistfight with a brother officer.

Johnny the Hard’s commanding officer, Major Smedley D. Butler, determined that another marginal fitness report or even transferring the seemingly troublesome Hughes out of his battalion was less punishment than deserved. On 24 May 1912, Butler cabled Major General Commandant William P. Biddle: “Consider Captain Hughes menace to welfare command. Request return to arrest or immediate detachment.” When the commandant rebuffed Butler’s request to transfer Hughes, not only out of Nicaragua but to the Philippines to begin anew the customary overseas posting of 2 to 2½ years, the major turned to an influential connection. Butler’s father, Congressman Thomas S. Butler, served on the powerful House Naval Affairs Committee as its senior Republican member.

The appeal to transfer Hughes passed quickly from Capitol Hill to Secretary Myer. But he denied the unusual and punitive request, leaving the younger Butler to deal with the obstreperous Johnny the Hard. Secretary Myer realized that the indefatigable Butler had attempted to embellish the original charge against Hughes. First, he added an incident of drunkenness that occurred two months prior to the assault on the junior officer; then Butler cited Hughes’ abusive language to him in an incident that took place a year before that.

No further incidents appeared on subsequent fitness reports prepared in Nicaragua, but two instances of Johnny the Hard as AWOL were noted while he served in Cuba; after the second occurrence, his battalion commander placed him on restriction. Hughes stood detached at the end of 1912 for duty at the barracks in Portsmouth, Rhode Island. Less than a year later, Headquarters Marine Corps ordered all of the barracks on the East Coast to provide the personnel to man the two regiments of the Advance Base Force in the forthcoming Fleet maneuvers.

Hughes reported to the 2nd Advance Base Regiment, forming up at the Philadelphia Navy Yard and scheduled for deployment to the Caribbean in the transport Prairie. As a captain, he led a company of infantry, one of four in a regiment (the “mobile regiment”) commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John A. Lejeune that also included a company of machine guns and a 3-inch naval gun battery.

On 27 November 1913, the Prairie stood to and steamed for New Orleans in anticipation of participating in Fleet maneuvers and the first test of the advance base concept, or quite possibly deploying to Mexico as relations with America’s southern neighbor worsened. The Hancock, containing the 1st Advance Base Regiment (the fixed regiment with large naval guns, search lights, and mining equipment) and the brigade headquarters followed on 3 January 1914.

Four days later, the two ships rendezvoused at sea off the Puerto Rican island of Culebra and dropped anchor. For the next two weeks, the Marines fortified the tiny island in earnest. When the opposing “Black Fleet” arrived, the chief umpire declared the island secure and a victory for the defenders. After training ashore, the force deployed to New Orleans on 9 February. But on 5 March, the ships embarking the Advance Base Force weighed anchor and steamed south for Mexico.

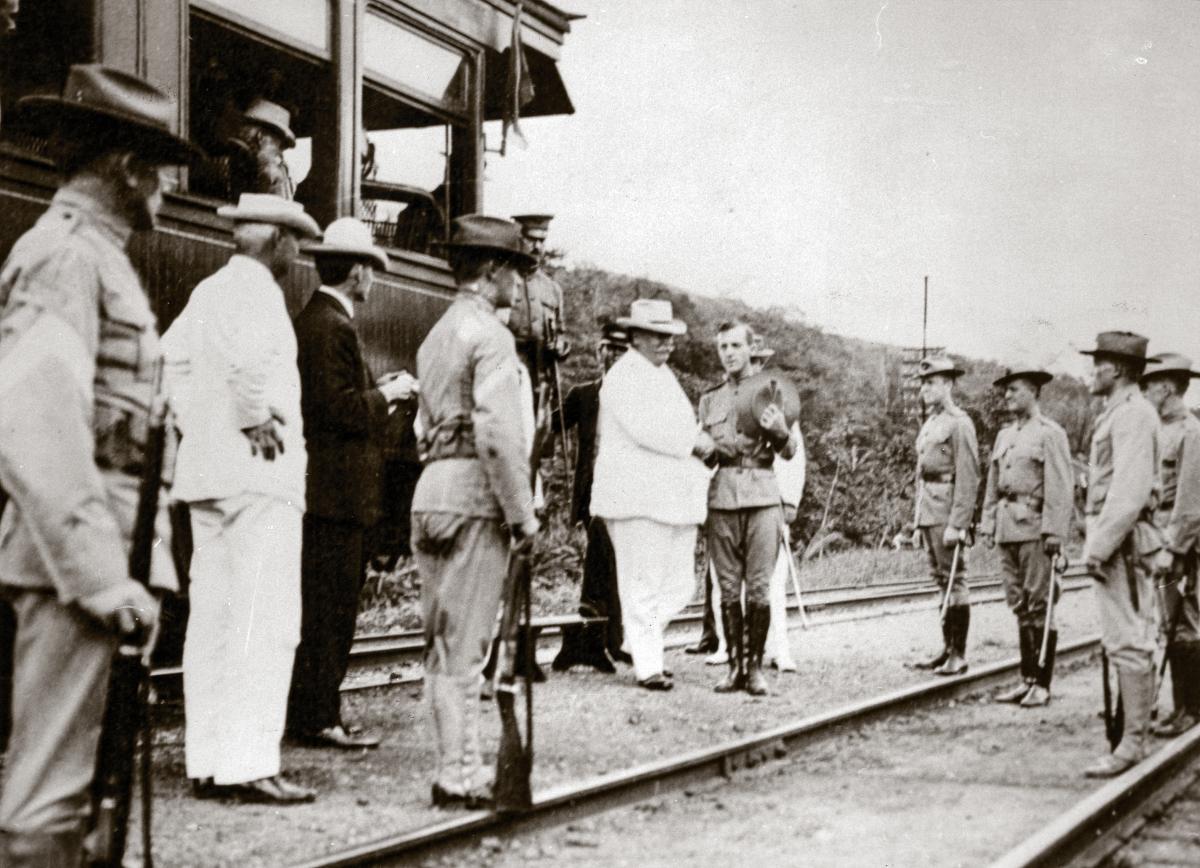

Into Veracruz

President Woodrow Wilson ordered the infantry components of the sizeable naval force into Veracruz, and Hughes deployed ashore with the 15th Company, 2d Provisional Regiment, on 21 April. For his conduct during the next two days, Hughes earned the Medal of Honor. Although heretofore awards of the nation’s highest decoration had been earned by both Army officers and enlisted personnel, the legislation provided only for the award to be presented to Sailors and enlisted Marines. After the incursion into Mexico, Congress amended the legislation for the Medal of Honor to include naval officers. The Department of the Navy took the opportunity to shower the Medal of Honor on selected participants at Veracruz. Of the Navy contingent deployed, 28 officers and 18 enlisted men earned the award; nine Marine Corps officers but none of the enlisted Leathernecks received the medal.

Butler pleaded with his superiors to have the award withdrawn, arguing that nothing in his citation warranted such recognition at that level. Waiving his protestations aside, the Department of the Navy ordered Butler to wear the award and cease his carping. How Hughes felt about the award is a footnote that has long slipped into the dustbin of history. Butler’s discomfit over his decoration must have intensified on learning that a fellow recipient of the nation’s highest decoration was an officer whom he despised.

When the brigade steamed north, Hughes received orders detaching him to the barracks in Portsmouth, and he joined his new command on 9 December 1914. In his final fitness report covering the landing at Veracruz, prepared by Major Randolph C. Berkeley—who also earned the Medal of Honor in Mexico—Hughes’ battalion commander wrote that “I cannot recommend this officer for the duties of a post commander, on account of his irritable temperament, which causes him to be needlessly harsh in handling the men under his command.”

Apparently, Johnny the Hard kept his nose fairly clean for the next 18 months. But in April 1916, the barracks commander at Portsmouth suspended him from duty for ten days for participating in a hoax in which Hughes had sent false telegrams to officers regarding orders for duty. A month later, Major General Commandant George Barnett ordered him to command the Marine Detachment in the battleship Delaware. After Hughes and his Marines deployed ashore in response to civil unrest and banditry in the Dominican Republic in 1916, President Wilson ordered the U.S. incursion a semi-permanent one on 26 October of that year.

Meanwhile, Hughes came up for what should have been a routine promotion to major based on a total of 15 years’ service and within the promotion zone established by strict lineal precedence. How Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels came to concern himself with the promotion of a Marine Corps captain to major is unclear. Most likely, the indefatigable and irrepressible Butler had a hand in alerting the pompous and egalitarian Daniels to the possibility that a junior officer of such unmilitary demeanor was about to become a field-grade officer. Barnett pleaded Hughes’ case, but to no avail. Besides his fitness reports and medical record, the case file contained two letters reporting Hughes’ suspension from duty and three letters of reprimand. But it also held a citation for the Medal of Honor.

Gunshot Wound to the Leg

Just then, however, a telegram arrived from Santo Domingo with the news that Johnny the Hard had suffered a gunshot wound to the left leg, fracturing his femur and inflicting severe damage to tissue and nerves. Barnett simply waved the telegram in Daniels’ face and forced the portentous secretary of the Navy to back down. Earlier, Daniels had demonstrated a fondness for exclaiming that his policy was to “reward those who have been at the cannon’s mouth,” or otherwise reward those members of the naval services with powder burns and tropical sweat stains on their uniforms.

Hughes’ promotion became effective 16 March 1917, and it arrived with a strongly worded letter of caution over the signature of the secretary of the Navy: “You are informed, however, that the Department [of the Navy] fully expects you to show your appreciation of the leniency thus exercised in your case by so conducting yourself in the future as to obviate the possibility of ever again being charged with drunkenness or harshness towards the men under your command.”

After Hughes recovered from his wound, he served at the headquarters of the Advance Base Force at Philadelphia. When the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, he received orders transferring him to Quantico in anticipation of Marine forces assembling for service in France. Shortly after the United States entered the war, John Lejeune, then a brigadier general, wrote excitedly to his friend in Haiti, Butler, with the news that Barnett had offered a brigade of Marines to join the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) bound for the Western Front. Assuming that he would command the brigade, Lejeune assured Butler—then only a major but holding the temporary rank of major general in the Gendarmerie d’Haiti—that he could promise him the command of a battalion of infantry.

Subsequently, when the initial deployment was reduced to only a regiment, a disconsolate Lejeune informed Butler that a colonel would command the regiment and he had no say in personnel matters. But Lejeune was being less than candid with his old friend. By then, the indefatigable Butler had already bombarded Headquarters Marine Corps with requests for relief of duties in Haiti and orders to France. Unmoved, Barnett ignored the entreaties by proclaiming Butler’s position simply too important to the success of the naval mission to Haiti. Privately, however, he snarled that Butler had used all of his political leverage to gain the coveted post to command the Gendarmerie d’ Haiti and he could just remain there. Meanwhile, Barnett turned to Lejeune for recommendations on just which officers should command the battalions and regiments that would ultimately constitute the 4th Brigade (Marine), AEF. The assistant to the commandant recommended Hughes to command one of the infantry battalions.

Off to the Western Front

Between July and August 1917, the 6th Marines assembled at Quantico. Colonel Albertus W. Catlin led the regiment. Hughes took command of 1/6, Thomas Holcomb 2/6, and Berton W. Sibley 3/6. On 16 September, Johnny the Hard and 1/6 departed Quantico by train for the Philadelphia Navy Yard for embarkation. Finally, on 23 September, the Henderson weighed anchor in the harbor of New York, steamed for France, and deposited Hughes’ battalion at St. Nazaire. In response to a request from AEF headquarters, Hughes and 12 of his fellow officers were detached for duty under instruction at the I Corps school at Gondrecourt from 19 October to 20 November. Apparently because of his stellar performance, Army superiors asked to keep Johnny the Hard there as an instructor. After teaching at the Army school from 31 December until 13 February 1918, Hughes requested a return to his battalion. Rebuffed by his Army superiors, he simply packed up and returned without orders. Presumably, someone in the chain of command from the 6th Marines to 4th Brigade (Marine) to 2d Division to I Corps sorted out the affair, because no mention of it appears in Johnny the Hard’s record. Subsequently, Hughes commanded 1/6 in one of the most ferocious and costly encounters of bloodletting in the history of the Marine Corps.

On 27 May 1918, Germany launched the third of its spring counteroffensives in hopes of bringing the war to a close before the full weight of America’s military might arrived on the Western Front. Within four days, the gray-clad feldgrau had reached the Marne River at Château-Thierry and threatened Paris 35 miles to the southwest. Although the United States had consistently refused the entreaties of its allies to enter the newly arrived American force into the lines until an entire army could be formed, the gravity of the situation caused that ukase to be set aside. Three American divisions rushed to stem the tide, including the 2d Division, AEF, which included the 4th Brigade (Marine).

The 6th Marines took up positions along the Paris-Metz highway, just south of a small forest called Belleau Wood, with orders to dig in and hold at all costs. Once their withering fire stalled the German advance, the Marines received orders to expel the enemy from Belleau Wood. Between then and when commanders declared the contested terrain secured on 23 June, the brigade suffered a horrendous casualty rate of more than 50 percent. For his conduct on 10-13 June 1918, Johnny the Hard earned both a Navy Cross and a Silver Star “for leading his men superbly under the most trying conditions against the most distinguished elements of the German Army, administering . . . their first defeat.” In the process, the gallant Marine suffered another combat wound, this time from poison gas that seared his lungs. More than half of 1/6 suffered wounds or died during those hellish days at Belleau Wood.

Not deterred by the licking inflicted on its forces by the fresh American troops and newly revitalized French soldiers, the German high command ordered the highway cut between Soissons and Château-Thierry. The Marine Brigade deployed south of Soissons on 18 July. In two days of bitter fighting, the Marines suffered almost 2,000 casualties. Most of the dead and wounded were among the ranks of the 6th Marines. Included in that number was Johnny A. Hughes, banged up badly when an enemy shell struck his command bunker.

Another Silver Star and Two Croix de Guerre

By then, his old gunshot wound from Santo Domingo had reopened and made even simple movement difficult and painful. Hughes’ gas-seared lungs sapped his strength. Determining that Johnny the Hard had reached the limit of endurance, his superiors effected his relief and ordered him home. An observer recalled that Hughes took a nasty fall as the bunker collapsed: “Johnny the Hard swore, then asked, ‘Any of you birds got a pair of wire cutters?’ He then cut off a shard of bone protruding from his leg.”

His promotion to lieutenant colonel, effective 28 August, finally caught up with him. Besides another Silver Star earned at Soissons, Hughes earned two Croix de Guerre. No less an icon than Colonel Hiram I. “Hikin’ Hiram” Bearss (a Medal of Honor recipient for his heroism on the Philippine island of Samar in 1901) thought Johnny the Hard deserved more. Writing from the Philadelphia Navy Yard a year later, where both colorful officers served with the Advance Base Force, Bearss sent his recommendation for the Medal of Honor directly to Commandant Barnett:

During the engagement to the east of Vierzy, on the 19th of July 1918, Lieut. Col. Hughes (then major) conducted his battalion across open fields swept by violent machine-gun and artillery fire. His entire commissioned and non-commissioned staff were either killed or wounded. Though suffering the severest pain from an old wound, he led his battalion forward and by his dauntless courage, [and] bulldog tenacity of purpose, set an example to his command that enabled [it] to hold [its] position against the enemy throughout the day [and] night, though without food or water and with very little ammunition. Major Hughes’ battalion had been reduced to about 200 men, but due to this magnificent example of gallantry and intrepidity this remnant of a battalion held a front of over 1,200 yards. As a battalion commander, he risked his life beyond the call of duty.

Just as resolutely, the commandant returned the recommendation, noting that it should have been submitted through the chain of command to Headquarters, AEF. By then, of course, too much time had elapsed. In any event, no officer serving in the 4th Brigade (Marine) earned the Medal of Honor in World War I.

Butler Makes It to France

At about the time Johnny the Hard fought his last combat, his old nemesis, Smedley Butler, finally made it to France. Congressman Butler simply side-stepped the commandant and went to Secretary Daniels, and the latter ordered Barnett to assign the younger Butler to an outfit slated for embarkation to the Western Front. All too quickly, Butler jumped from major to lieutenant colonel, and then to colonel in command of the 13th Marines. But throughout the summer of 1918, senior Army officers and Secretary of War Newton Baker balked at accepting another brigade of Marines in France. Butler finally embarked with his regiment on 15 September and arrived in France two weeks later.

To his bitter disappointment, AEF headquarters ordered the 5th Brigade of Marines broken up for replacements and to perform duties along the lines of communication. Newly promoted to brigadier general, Butler dejectedly took command of a depot division at the AEF processing center at Pontanezen. For his wartime service, the indefatigable campaigner earned both the Army and the Navy Distinguished Service Medals and the French Order of the Black Star, a decoration designed to recognize the service of noncombatants. To his parents, Butler complained that “for over twenty years, I worked hard to fit myself to take part in this war which has just closed, and now when the supreme test came my country did not want me.”

Detached from a hospital in France in December 1918, Hughes embarked on the Mercy for the journey home. After two months in the naval hospital in Philadelphia, he attempted active service with the Advance Base Force at the navy yard but to no avail. Johnny the Hard had led his last charge; combat wounds resulted in a transfer to the disability retired list on 3 July 1919.

In retirement, Hughes joined his brothers in a commercial enterprise in Manhattan, the Hughes Trading Company. In a footnote to history, he provided the cover story for Marine Lieutenant Colonel Earl H. “Pete” Ellis’ ill-fated spy mission to the Central Pacific in 1923. (Ellis took the identity of a salesman for the Hughes company as a cover for the bizarre escapade.) Two years later, Hughes left New York to take up a position as a salesman for Mack Trucking in Cleveland and then became the first director of the Ohio Liquor Control Department in 1933-34. In 1936, the square-jawed, tough Marine became the safety director at the Great Lakes Exposition. Ill health from his combat wounds and tropical soldiering forced Hughes to retire again in 1937, and he moved to Florida. The gallant Marine slipped away on 25 May 1942 after a long stay in a veterans’ hospital. A generation of Leathernecks remembered the resolute Marine, known by all who admired or feared or despised him, as Johnny the Hard.

Note on sources: Hughes’ service files are found in enlisted records, Entry 75, records of the U. S. Marine Corps, Record Group (RG) 127, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), and Entry 62, Records of Marine Corps Examining Boards, RG 120, NARA; he left no personal papers. Butler’s personal papers are found at the Marine Corps Research Center, Quantico and those of John A. Lejeune in the Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress (MD, LC). Congressman Butler’s papers were destroyed after his death, but the voluminous collection of correspondence from and to Secretary Daniels is at the MD, LC.