Category: This great Nation & Its People

Carlos Hathcock at work in the fields of Vietnam. (Photo: U.S. Marine Corps)

Long before Chris Kyle penned “American Sniper,” Carlos Hathcock was already a legend.

He taught himself to shoot as a boy, just like Alvin York and Audie Murphy before him.

He had dreamed of being a U.S. Marine his whole life and enlisted in 1959 at just 17 years old.

Hathcock was an excellent sharpshooter by then, winning the Wimbledon Cup shooting championship in 1965, the year before he would deploy to Vietnam and change the face of American warfare forever.

He deployed in 1966 as a military policeman, but immediately volunteered for combat and was soon transferred to the 1st Marine Division Sniper Platoon, stationed at Hill 55, South of Da Nang.

This is where Hathcock would earn the nickname “White Feather” — because he always wore a white feather on his bush hat, daring the North Vietnamese to spot him — and where he would achieve his status as the Vietnam War’s deadliest sniper in missions that sound like they were pulled from the pages of Marvel comics.

White Feather vs. The General

Early morning and early evening were Hathcock’s favorite times to strike. This was important when he volunteered for a mission he knew nothing about.

“First light and last light are the best times,” he said. “ In the morning, they’re going out after a good night’s rest, smoking, laughing. When they come back in the evenings, they’re tired, lollygagging, not paying attention to detail.”

He observed this first hand, at arm’s reach, when trying to dispatch a North Vietnamese Army General officer.

For four days and three nights, he low crawled inch by inch, a move he called “worming,” without food or sleep, more than 1500 yards to get close to the general. This was the only time he ever removed the feather from his cap.

“Over a time period like that you could forget the strategy, forget the rules and end up dead,” he said. “I didn’t want anyone dead, so I took the mission myself, figuring I was better than the rest of them, because I was training them.”

Hathcock moved to a treeline near the NVA encampment.

“There were two twin .51s next to me,“ he said. “I started worming on my side to keep my slug trail thin. I could have tripped the patrols that came by.”

The general stepped out onto a porch and yawned. The general’s aide stepped in front of him and by the time he moved away, the general was down, the bullet went through his heart. Hathcock was 700 yards away.

“I had to get away. When I made the shot, everyone ran to the treeline because that’s where the cover was.” The soldiers searched for the sniper for three days as he made his way back. They never even saw him.

“Carlos became part of the environment,” said Edward Land, Hathcock’s commanding officer. “He totally integrated himself into the environment. He had the patience, drive, and courage to do the job. He felt very strongly that he was saving Marine lives.”

With 93 confirmed kills – his longest was at 2,500 yards – and an estimated 300 more, for Hathcock, it really wasn’t about the killing.

“I really didn’t like the killing,” he once told a reporter. “You’d have to be crazy to enjoy running around the woods, killing people. But if I didn’t get the enemy, they were going to kill the kids over there.”

Saving American lives is something Hathcock took to heart.

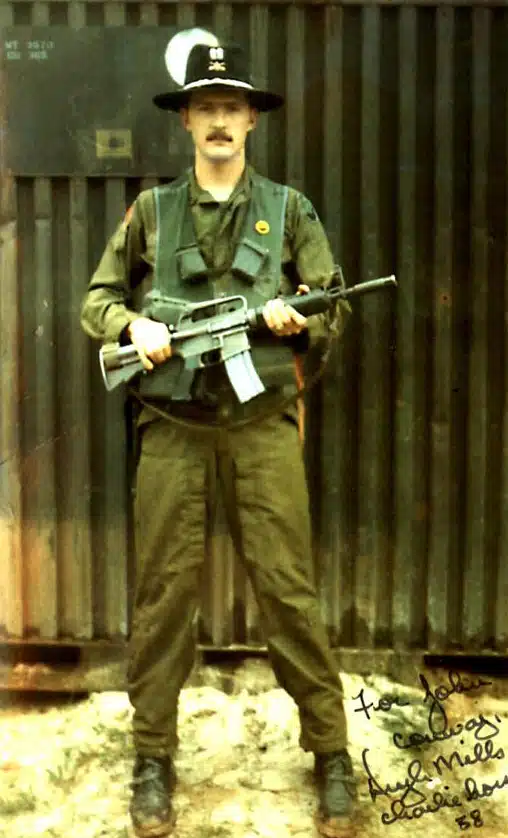

Carlos Hathcock, in camp (left), and ready to go out on a kill mission (right).

“The Best Shot I Ever Made”

“She was a bad woman,” Carlos Hathcock once said of the woman known as ‘Apache.’

“Normally kill squads would just kill a Marine and take his shoes or whatever, but the Apache was very sadistic. She would do anything to cause pain.”

This was the trademark of the female Viet Cong platoon leader. She captured Americans in the area around Carlos Hathcock’s unit and then tortured them without mercy.

“I was in her backyard, she was in mine. I didn’t like that,” Hathcock said. “It was personal, very personal. She’d been torturing Marines before I got there.”

In November of 1966, she captured a Marine Private and tortured him within earshot of his own unit.

“She tortured him all afternoon, half the next day,” Hathcock recalls. “I was by the wire… He walked out, died right by the wire.”

Apache skinned the private, cut off his eyelids, removed his fingernails, and then castrated him before letting him go. Hathcock attempted to save him, but he was too late.

Carlos Hathcock had had enough. He set out to kill Apache before she could kill any more Marines.

One day, he and his spotter got a chance. They observed an NVA sniper platoon on the move. At 700 yards in, one of them stepped off the trail and Hathcock took what he calls the best shot he ever made.

“We were in the midst of switching rifles. We saw them,” he remembered. “I saw a group coming, five of them. I saw her squat to pee, that’s how I knew it was her. They tried to get her to stop, but she didn’t stop. I stopped her. I put one extra in her for good measure.”

Women were a regular part of the Viet Cong, like the evil torturer “The Apache”

A Five-Day Engagement

One day during a forward observation mission, Hathcock and his spotter encountered a newly minted company of NVA troops. They had new uniforms, but no support and no communications.

“They had the bad luck of coming up against us,” he said. “They came right up the middle of the rice paddy. I dumped the officer in front, my observer dumped the one in the back.”

The last officer started running the opposite direction.

“Running across a rice paddy is not conducive to good health,” Hathcock remarked. “You don’t run across rice paddies very fast.”

NVA and Viet Cong troops in action somewhere in Vietnam.

According to Hathcock, once a Sniper fires three shots, he leaves. With no leaders left, after three shots, the opposing platoon wasn’t moving.

“So there was no reason for us to go either,” said the sniper. “No one in charge, a bunch of Ho Chi Minh’s finest young go-getters, nothing but a bunch of hamburgers out there.”

Hathcock called artillery at all times through the coming night, with flares going on the whole time.

When morning came, the NVA were still there.

“We didn’t withdraw, we just moved,” Hathcock recalled. “They attacked where we were the day before. That didn’t get far either.”

White Feather and The M2

Though the practice had been in use since the Korean War, Carlos Hathcock made the use of the M2 .50 caliber machine gun as a long-range sniper weapon a normal practice. He designed a rifle mount, built by Navy Seabees, which allowed him to easily convert the weapon.

M25 rifle

“I was sent to see if that would work,” he recalled. “We were elevated on a mountain with bad guys all over. I was there three days, observing. On the third day, I zeroed at 1,000 yards, longest 2,500. Here comes the hamburger, came right across the spot where it was zeroed, he bent over to brush his teeth and I let it fly. If he hadn’t stood up, it would have gone over his head. But it didn’t.”

The distance of that shot was 2,460 yards – almost a mile and a half – and it stood as a record until broken in 2002 by Canadian sniper Arron Perry in Afghanistan.

White Feather vs. The Cobra

“If I hadn’t gotten him just then,” Hathcock remembers, “he would have gotten me.”

Many American snipers had a bounty on their heads. These were usually worth one or two thousand dollars. The reward for the sniper with the white feather in his bush cap, however, was worth $30,000.

Like a sequel to Enemy at The Gates, Hathcock became such a thorn in the side of the NVA that they eventually sent their own best sniper to kill him. He was known as the Cobra and would become Hathcock’s most famous encounter in the course of the war.

“He was doing bad things,” Hathcock said. “He was sent to get me, which I didn’t really appreciate. He killed a gunny outside my hooch. I watched him die. I vowed I would get him some way or another.”

That was the plan. The Cobra would kill many Marines around Hill 55 in an attempt to draw Hathcock out of his base.

“I got my partner, we went out we trailed him. He was very cagey, very smart. He was close to being as good as I was… But no way, ain’t no way ain’t nobody that good.”

In an interview filmed in the 1990s, He discussed how close he and his partner came to being a victim of the Cobra.

“I fell over a rotted tree. I made a mistake and he made a shot. He hit my partner’s canteen. We thought he’d been hit because we felt the warmness running over his leg. But he’d just shot his canteen dead.”

Eventually the team of Hathcock and his partner, John Burke, and the Cobra had switched places.

“We worked around to where he was,” Hathcock said. “I took his old spot, he took my old spot, which was bad news for him because he was facing the sun and glinted off the lens of his scope, I saw the glint and shot the glint.” White Feather had shot the Cobra just moments before the Cobra would have taken his own shot.

“I was just quicker on the trigger otherwise he would have killed me,” Hathcock said. “I shot right straight through his scope, didn’t touch the sides.”

With a wry smile, he added: “And it didn’t do his eyesight no good either.“

1969, a vehicle Hathcock was riding in struck a landmine and knocked the Marine unconscious. He came to and pulled seven of his fellow Marines from the burning wreckage. He left Vietnam with burns over 40 percent of his body. He received the Silver Star for this action in 1996.

Lieutenant General P. K. Van Riper, Commanding General Marine Corps Combat Development Command, congratulates Gunnery Sgt. Carlos Hathcock (Ret.) after presenting him the Silver Star during a ceremony at the Weapons Training Battalion. Standing next to Gunnery Sgt. Hathcock is his son, Staff Sgt. Carlos Hathcock, Jr.

After the mine ended his sniping career, he established the Marine Sniper School at Quantico, teaching Marines how to “get into the bubble,” a state of complete concentration. He was in intense pain as he taught at Quantico, suffering from Multiple Sclerosis, the disease that would ultimately kill him — something the NVA could never accomplish.

Rick Atkinson says in “An Army At Dawn” that Patton fired his revolvers at the FW-190s that strafed his HQ in Gafsa, Tunisia on April 3 ‘43. This event was portrayed in the Patton movie.

As I recall they were able to use Patton’s real pistols but in a scene firing blanks, not so much. Actor Scott pulled a semi-auto pistol in the movie.

Maybe the same pistol he was carrying when he decorated these soldiers late in WWII.

Another time in North Africa he was riding in an open car with a French official. They were fired on by an Arab. Patton fired on this guy but I believe with his semi-auto pistol. No hits.

In the field with Bradley and the Meteor of Mediocrity.

The .45 cal Colt Peacemaker on the bottom of this pic has two notches on the handle for the Mexican banditos Patton dropped in Mexico. The other pistol is a .357 magnum. He had other revolvers.

When World War Two ended Patton said, “Thus endeth the second lesson.”

Anyone who ever flew an Army helicopter reveres the Loach. Uncle Sam called the bizarre little egg-shaped aircraft the OH-6A Cayuse. Its official classification was Light Observation Helicopter, hence the informal appellation “Loach.” The Loach looks and sounds like a giant, angry bumble bee. It is a simply magnificent machine.

Anyone who ever flew an Army helicopter reveres the Loach. Uncle Sam called the bizarre little egg-shaped aircraft the OH-6A Cayuse. Its official classification was Light Observation Helicopter, hence the informal appellation “Loach.” The Loach looks and sounds like a giant, angry bumble bee. It is a simply magnificent machine.

The Loach was used for scouting missions during the Vietnam War. The aircraft was flown without doors at extremely low levels. The typical crew layout was a single pilot on the right with a crew chief sitting just behind on the same side, packing an M60 belt-fed machinegun suspended from a bungee cord. Offsetting the weight on the left was an M-134 minigun in an XM21E1 mount. This electrically-powered 7.62x51mm belt-fed Gatling gun cycled at either 2,000 or 4,000 rounds per minute via a two-stage trigger. It fed from a 2,000-round ammunition magazine. The pilot sighted the minigun via a grease pencil mark on the inside of the Plexiglas canopy.

The Loach operated most commonly as part of a Pink Team. In this configuration, the Loach cruised about down low in the dirt, looking for bad guys, while one or two AH-1G Cobra gunships orbited at altitude, waiting to dive in at the first sign of trouble. The two elements maintained constant radio contact. Experienced Pink Teams were devastating killers on the battlefield. Survival and tactical effectiveness demanded both nerves of steel and exceptional pilotage.

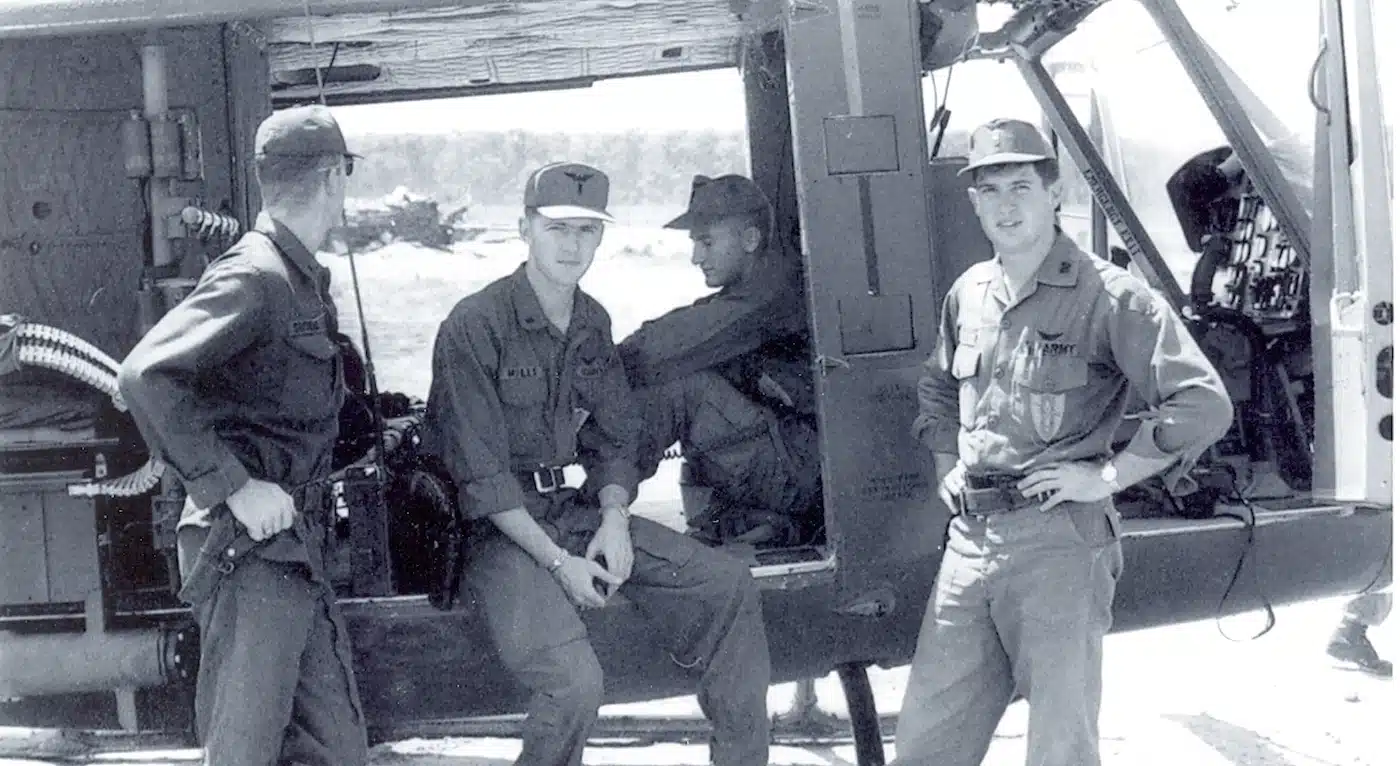

Of all the scout pilots who served in Vietnam, one name percolates above all the rest: Lt. Col. Hugh Mills. He is a legend among Army aviators, even today. A Loach painted as his distinctive “Miss Clawd IV”, dangles proudly from the ceiling at the Army Aviation Museum at Fort Rucker. Among rotary-wing aviators, that is the Army’s highest accolade. Lt. Col. Mills earned every bit of that love.

A Hard Day in Hell

In the summer of 1969, then-Lieutenant High Mills piloted his agile little Loach as the bottom half of a hunter-killer Pink Team. In the back was his regular crew chief, Jim Parker. Mills and Parker had flown together for months and were forged into an exceptionally effective scout team. On this fateful day, they were clearing the route for a supply convoy along a length of highway called Thunder Road.

Without warning, Mills’ Loach was engaged by a well-sited VC .50-caliber machine gun. One of the big thumb-sized rounds punched through the leading edge of one of the Loach’s four rotor blades about four feet from the tip. There resulted a skull-crushing vibration as the hearty Loach clawed to stay in the air.

Mills retained control of the stricken aircraft, but only just. He guided the doomed helicopter to a controlled crash on a nearby flat piece of rice paddy. Parker split his chin on the front sight of his M60, but both aviators were otherwise unhurt. They cleared the aircraft with Parker’s M60 and a seven-foot belt of ammo along with Mills’ CAR-15 and a bandoleer of magazines.

Mills spotted a pair of VC soldiers shooting at them with AK-47s from about 175 yards away. He fired a burst from his CAR-15 as Parker sprayed the area with his M60. Both enemy soldiers fell, but they just kicked over the anthill.

A substantial VC force began slathering the crash site with fire and moving toward the two trapped aviators. Parker returned to the crashed aircraft to retrieve more M60 ammo as Mills covered him with his CAR-15. Meanwhile, the high-cover Snake pummeled the tree line with 2.75″ rockets and minigun fire. However, the Cobra soon ran out of ammo.

Just when it seemed like all was lost, a nearby Infantry Brigade commander in a command-and-control aircraft dropped down to make an emergency extraction. Parker and Mills clambered aboard the hovering Huey and made their escape before the remaining VC could stop them.

Turning an NVA Pot into a Colander

During that same summer, Mills and Parker were tearing along in their Loach on a routine trip into Dau Tieng for a briefing. They had a G-model Cobra flying top cover. As they pitched over a ridgeline, Mills surprised an NVA heavy weapons platoon on the march. Without hesitation, he opened up with his minigun at close range as Parker unlimbered his M60. The NVA troops answered with a fusillade of AK-47 fire.

A pair of NVA soldiers tore off down a paddy dike toward the wood line and cover. The nearer of the two enemy soldiers carried a big cooking pot that flapped against his back as he ran. Mills quickly pivoted his nimble little aircraft, lined up the grease pencil mark on his canopy and triggered a quick squirt from his minigun. His burst passed through the nearest NVA soldier and into his buddy, killing them both.

Mills chased the remaining NVA troops around the paddy until both he and Parker ran out of ammo. Parker then unlimbered both his M16 as well as a 12-gauge pump shotgun. Meanwhile, Mills steadied the collective lever with his knee and emptied six rounds left-handed from his personal .357 Magnum revolver at the fleeing enemy troops. Once completely out of ammunition, Mills rolled clear so the orbiting Snake could pulverize the area with 2.75″ rockets packing flechette warheads.

In two minutes of unfettered combat, their Loach had been hit 25 times. The airspeed indicator and altimeter were both blown away, and the armor plate underneath Parker’s seat had caught two rounds. Mills’ seat armor stopped several more. Five rounds shattered the Plexiglas canopy, two hit the tail boom, and another three struck the rotor blades. One AK round transited the engine compartment but missed anything significant. Another shot the op rod off of Parker’s M60.

Supporting ARP (Aero Rifle Platoon) grunts subsequently inserted and swept the area. They cataloged 26 KIA and seized a pair of POWs along with a large number of AK-47 rifles, an SGM heavy machinegun, a 60mm mortar and a pair of Russian pistols. When they returned to base, the infantry troops presented Lt. Col. Mills with a cooking pot sporting 24 bullet holes.

The Rest of the Story

While serving three combat tours in Vietnam, Lt. Col. Hugh Mills earned three Silver Stars, three Bronze Stars, four Distinguished Flying Crosses, and the Legion of Merit. He was shot down an amazing 16 times and was wounded three times in combat. He ultimately flew 3,300 combat hours in OH-6A and AH-1G helicopters. His record as a combat aviator will never be bested.

The OH-6A was tragically replaced by the Bell OH-58 in Army service. Both aircraft shared a common engine, but in my opinion the Loach was a massively better aircraft. I flew OH-58’s myself, and we all mourned the passing of the Loach. However, that was not the last Uncle Sam saw of this extraordinary little machine.

The Task Force 160 SOAR (Special Operations Aviation Regiment), better known as the Night Stalkers, adopted the OH-6 in an upgraded form as the MH-6 Little Bird. They call it the “Killer Egg.” These immensely capable machines feature an upgraded powertrain along with a more efficient five-bladed rotor system. The Night Stalkers use both an armed gunship version of the aircraft as well as slick-sided variant designed for covert insertion of special operators in places where stealth and speed are of the essence. If ever I win the lottery, my first call will be to my wife. My second will be to Boeing to pick up an MH-6 of my own.

Lt. Col. Mills penned a book about his exploits in Vietnam titled Low Level Hell. It is an amazing read that is just packed with action along with plenty of cool commentary about small arms. It is available on Amazon.