Category: The Green Machine

|

Joe Ronnie Hooper

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | August 8, 1938 Piedmont, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | May 6, 1979 (aged 40) Louisville, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1956–1959 (USN) 1960–1978 (USA) |

| Rank | |

| Unit | |

| Battles/wars | Vietnam War (WIA) |

| Awards | |

Joe Ronnie Hooper (August 8, 1938 – May 6, 1979) was an American who served in both the United States Navy and United States Army where he finished his career there as a captain. He earned the Medal of Honor while serving as an army staff sergeant on February 21, 1968, during the Vietnam War. He was one of the most decorated U.S. soldiers of the war and was wounded in action eight times.

Early life and education[edit]

Hooper was born on August 8, 1938, in Piedmont, South Carolina. His family moved when he was a child to Moses Lake, Washington where he attended Moses Lake High School.

Career[edit]

Hooper enlisted in the United States Navy in December 1956. After graduation from boot camp at San Diego, California he served as an Airman aboard USS Wasp and USS Hancock. He was honorably discharged in July 1959, shortly after being advanced to petty officer third class.

U.S. Army

Hooper enlisted in the United States Army in May 1960 as a private first class, and attended Basic Training at Fort Ord, California. After graduation, he volunteered for Airborne School at Fort Benning, Georgia, then was assigned to Company C, 1st Airborne Battle Group, 325th Infantry,[1] 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and was promoted to corporal during this assignment.

He served a tour of duty in South Korea with the 20th Infantry in October 1961, and shortly after arriving, he was promoted to sergeant and was made a squad leader. He left Korea in November 1963, and was assigned to the 2nd Armored Division at Fort Hood, Texas for a year as a squad leader, then became a squad leader with Company D, 2nd Battalion (Airborne), 502nd Infantry, 101st Airborne Division at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

He was promoted to staff sergeant in September 1966, and volunteered for service in South Vietnam. Instead, he was assigned as a platoon sergeant in Panama with the 3rd Battalion (Airborne), 508th Infantry, first with HQ Company and later with Company B.

Hooper could not stay out of trouble, and suffered several Article 15 hearings, then was reduced to the rank of corporal in July 1967. He was promoted once again to sergeant in October 1967, and was assigned to Company D, 2nd Battalion (Airborne), 501st Airborne Infantry, 101st Airborne Division at Fort Campbell, and deployed with the division to South Vietnam in December as a squad leader.

During his tour of duty with Delta Company (Delta Raiders), 2nd Battalion (Airborne), 501st Airborne Infantry, he was recommended for the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions on February 21, 1968, during the Battle of Huế.[2]

He returned from South Vietnam, and was discharged in June 1968. He re-enlisted in the Army the following September, and served as a public relations specialist. On March 7, 1969, he was presented the Medal of Honor by President Richard Nixon during a ceremony in the White House. From July 1969 to August 1970, he served as a platoon sergeant with the 3rd Battalion, 5th Infantry in Panama.

He managed to finagle a second tour in South Vietnam; from April to June 1970, he served as a pathfinder with the 101st Aviation Group, 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile), and from June to December 1970, he served as a platoon sergeant with Company A, 2nd Battalion, 327th Infantry, 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile).

In December 1970, he received a direct commission to second lieutenant and served as a platoon leader with Company A, 2nd Battalion, 501st Infantry, 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile) until April 1971.

Upon his return to the United States, he attended the Infantry Officer Basic Course at Fort Benning, and was assigned as an instructor at Fort Polk, Louisiana. Despite wanting to serve twenty years in the Army, Hooper was made to retire in February 1974 as a first lieutenant, mainly because he only completed a handful of college courses beyond his GED.

As soon as he was released from active duty, he joined a unit of the Army Reserve’s 12th Special Forces Group (Airborne) in Washington as a Company Executive Officer. In February 1976, he transferred to the 104th Division (Training), also based in Washington. He was promoted to captain in March 1977. He attended drills intermittently, and was separated from the service in September 1978.

For his service in Vietnam, the U.S. Army also awarded Hooper two Silver Stars, six Bronze Stars, eight Purple Hearts, the Presidential Unit Citation, the Vietnam Service Medal with six campaign stars, and the Combat Infantryman Badge.

He is credited with 115 enemy killed in ground combat, 22 of which occurred on February 21, 1968. He became one of the most-decorated soldiers in the Vietnam War,[2] and was one of three soldiers wounded in action eight times in the war.

Later life and death

According to rumors, he was distressed by the anti-war politics of the time, and compensated with excessive drinking which contributed to his death.[3] He died of a cerebral hemorrhage in Louisville, Kentucky on May 6, 1979, at the age of 40.

Hooper is buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Section 46, adjacent to the Memorial Amphitheater.

Military awards

Hooper’s military decorations and awards include:

|

|||

| Combat Infantryman Badge | |||||||||||

| Medal of Honor | Silver Star w/ 1 bronze oak leaf cluster |

||||||||||

| Bronze Star w/ Valor device and 1 silver oak leaf cluster |

Purple Heart w/ 1 silver and 2 bronze oak leaf clusters |

Air Medal w/ 4 bronze oak leaf clusters |

|||||||||

| Army Commendation Medal w/ Valor device and 1 bronze oak leaf cluster |

Army Good Conduct Medal w/ 3 bronze Good conduct loops |

Navy Good Conduct Medal | |||||||||

| National Defense Service Medal | Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal | Vietnam Service Medal w/ 1 silver and 1 bronze campaign stars |

|||||||||

| Vietnam Cross of Gallantry w/ Palm |

Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal | Navy Pistol Marksmanship Ribbon w/ “E” Device |

|||||||||

| Army Presidential Unit Citation | ||

| Vietnam Presidential Unit Citation | Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross Unit Citation | Republic of Vietnam Civil Actions Unit Citation |

|

|

|

| Master Parachutist Badge | Expert Marksmanship Badge w/ 1 weapon bar |

Vietnam Parachutist Badge |

Medal of Honor citation

Medal of Honor

{{quote|Rank and organization: Staff Sergeant, U.S. Army, Company D, 2d Battalion (Airborne), 501st Infantry, 101st Airborne Division. Place and date: Near Huế, Republic of Vietnam, February 21, 1968. Entered service at: Los Angeles, Calif. Born: August 8, 1938, Piedmont, S.C.

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. Staff Sergeant (then Sgt.) Hooper, U.S. Army, distinguished himself while serving as squad leader with Company D. Company D was assaulting a heavily defended enemy position along a river bank when it encountered a withering hail of fire from rockets, machine guns and automatic weapons. S/Sgt. Hooper rallied several men and stormed across the river, overrunning several bunkers on the opposite shore.

Thus inspired, the rest of the company moved to the attack. With utter disregard for his own safety, he moved out under the intense fire again and pulled back the wounded, moving them to safety. During this act S/Sgt. Hooper was seriously wounded, but he refused medical aid and returned to his men. With the relentless enemy fire disrupting the attack, he single-handedly stormed 3 enemy bunkers, destroying them with hand grenade and rifle fire, and shot 2 enemy soldiers who had attacked and wounded the Chaplain. Leading his men forward in a sweep of the area, S/Sgt. Hooper destroyed 3 buildings housing enemy riflemen.

At this point he was attacked by a North Vietnamese officer whom he fatally wounded with his bayonet. Finding his men under heavy fire from a house to the front, he proceeded alone to the building, killing its occupants with rifle fire and grenades.

By now his initial body wound had been compounded by grenade fragments, yet despite the multiple wounds and loss of blood, he continued to lead his men against the intense enemy fire. As his squad reached the final line of enemy resistance, it received devastating fire from 4 bunkers in line on its left flank. S/Sgt. Hooper gathered several hand grenades and raced down a small trench which ran the length of the bunker line, tossing grenades into each bunker as he passed by, killing all but 2 of the occupants.

With these positions destroyed, he concentrated on the last bunkers facing his men, destroying the first with an incendiary grenade and neutralizing 2 more by rifle fire. He then raced across an open field, still under enemy fire, to rescue a wounded man who was trapped in a trench.

Upon reaching the man, he was faced by an armed enemy soldier whom he killed with a pistol. Moving his comrade to safety and returning to his men, he neutralized the final pocket of enemy resistance by fatally wounding 3 North Vietnamese officers with rifle fire. S/Sgt. Hooper then established a final line and reorganized his men, not accepting treatment until this was accomplished and not consenting to evacuation until the following morning.

His supreme valor, inspiring leadership and heroic self-sacrifice were directly responsible for the company’s success and provided a lasting example in personal courage for every man on the field. S/Sgt. Hooper’s actions were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself and the U.S. Army.

———————————————————————————— What a Stud!!! Grumpy

The Medal of Honor is instantly recognized as our nation’s highest award for heroism. The familiar words, “Above and beyond the call of duty” are etched into every child’s memory as dreams of battlefield gallantry flicker across their thoughts and deeds while engaged in playground antics. Few know, however, that while the Medal of Honor was instituted in March of 1863, we had other ways of recognizing gallantry that date back to the American Revolution.

The Medal of Honor is instantly recognized as our nation’s highest award for heroism. The familiar words, “Above and beyond the call of duty” are etched into every child’s memory as dreams of battlefield gallantry flicker across their thoughts and deeds while engaged in playground antics. Few know, however, that while the Medal of Honor was instituted in March of 1863, we had other ways of recognizing gallantry that date back to the American Revolution.

In August of 1782, Gen. Washington wrote: “The General … directs that whenever any singularly meritorious action is performed, the author of it shall be permitted to wear on his facings over the left breast, the figure of a heart in purple cloth, or silk, edged with narrow lace or binding. Not only instances of unusual gallantry, but also of extraordinary fidelity and essential service in any way shall meet with a due reward.” From that directive, we know of three “Purple Hearts for Military Merit” that were awarded to soldiers of the Continental Line and then the award fell into disuse and was eventually revived in 1932 as an award for being wounded in combat.

At the close of the American Revolution in 1781, Congress authorized the purchase and presentation of 15 swords to be made in Paris and inscribed with the thanks of Congress to the recipient—who had been nominated by Gen. Washington for superior service and gallantry. Eight of these swords are known to have survived.

During the War of 1812, Congress similarly presented 27 swords to those who had displayed gallantry at the Battle of Lake Erie. Eight are known to still exist today.

In another example, which is the only time Congress has presented an actual firearm to a soldier for heroism, at the Battle of Plattsburgh, N.Y., in 1814, 17 young men enlisted to help defend the city and received inscribed Hall’s rifles with personalized plaques that highlighted their service. Ten of these are accounted for today.

In March of 1863, six Medals of Honor were awarded at the War Dept. to the surviving soldiers who had taken part in the great locomotive chase later immortalized by Buster Keaton in the 1926 film “The General.” Inscriptions on the back read, “The Congress to …” and then the name, rank and location of the event were engraved upon the first medals given for valor in our military history.

Today, the Medal of Honor is our nation’s most-revered symbol of courage and gallantry. More than 3,000 have been earned since the Civil War, and those who survive to receive the award are held in high esteem for the rest of their lives.

Through the generosity of Norm Flayderman, Jack Lewis and Marvin Applewhite, the NRA National Firearms Museum has four original Medals of Honor in the collection. They are currently on exhibit, along with other symbols of valor that predate the Civil War.

Through the generosity of John McMurray, Craig Bell and Alan Boyd, of the American Society of Arms Collectors, the National Firearms Museum is pleased to announce the opening of Symbols of Valor, a collection of two of the Revolution’s presentation swords, two Lake Erie swords, one Plattsburgh Hall’s rifle and five Medals of Honor.

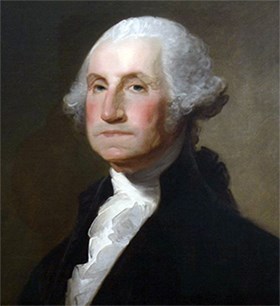

The exhibit is displayed with an original oil painting by Gilbert and Jane Stuart of George Washington, recently donated by the Estate of Doc Thurston of Charlotte, N.C.

———————————————————————————— In all my time in the Army. I have only met and promptly saluted one MOH man. Which should tell you that they are the elite of the elite of our Warriors! Grumpy

The American Airborne concept first suggested in World War I, became a need heading into World War II. The war started years before direct American involvement. The Airborne concept had to quickly yield results to support the allied cause, which at the time of its creation, was losing in both the Pacific and European theaters.

While there were no Airborne units in the American military, the airborne concept was nothing new to the Army. In 1918, it was Brigadier General William P. “Billy” Mitchell of the Army Air Corps, General John J. Pershing’s air service advisor in WWI, who first suggested the United States Army should utilize airborne troops.[1] Although “Black Jack” Pershing approved the idea, the concept never became reality due to the war ending of the war.

It would take another twenty-one years for the American Army to realize the paratroopers would be an important asset for future military operations. In 1939, when General George C. Marshall became the Army’s Chief of Staff, he made the recommendation to Major General George A. Lynch, Chief of the Infantry at the time, to “make a study for the purpose of determining the desirability of organizing, training and conducting tests of a small detachment of air infantry with a view to determine whether or not our Army should contain a unit or units of this nature.”[2]

Marshall recognized the potential and importance of possessing an Airborne asset. Even though some argued the Airborne concept was not a necessity for the Americans in WWII, General Marshall gave his approval on 25 July 1940. He authorized the War Department to immediately establish a Parachute Test Platoon to experiment with the development of airborne troops.[3]

Lieutenant General (Retired) Edward M. Flanagan defends the creation of the Airborne by pointing out in his book, Corregidor: The Rock Force Assault, the paratroopers served as a strategic asset with the ability to occupy the enemy commander’s mind for three reasons. First, while the enemy knows the airborne units exist, he does not know where they will strike.

Next, once they jump, the enemy must commit forces to engage the paratroopers, typically dropped over enemy vulnerabilities, such as their rear or flanks. Finally, the enemy never knows when the airborne attack might occur, leaving him in a constant state of high alert.[4]

Flanagan also highlighted that even when the drops were not a complete success and the paratroopers end up scattered, the enemy remained confused due to not knowing the size of the force, nor did he know where to concentrate his own force.

Because of how their drops disperse over a large area, paratroopers had the ability to deceive the enemy into thinking that their numbers were greater than what they actually were.[5] Flanagan cited Sicily as an example of the Airborne accomplishing this feat.

In Normandy, while the Airborne may not have succeeded in all of its D-Day objectives, it left the Germans in a constant state of confusion. The Airborne successfully defended the flanks and perimeter of the Normandy beachheads by freezing the German forces in place. The enemy’s confusion over an airborne drop easily became part of the element of surprise.

In the days following June 6th, 1944, the German Seventh Army chief of staff reported that “the ‘new weapon,’ the airborne troops, behind the coastal fortifications on the one hand, and their massive attack on our own counterattacking troops, on the other hand, have contributed significantly to the initial success of the enemy.”[6] From their appearance in the theater of war to the drops to the aftermath of the assault, paratroopers left their enemy in a disoriented and bewildered state. But before the Airborne would prove themselves on the battlefields of Europe, they had to start at the beginning, from scratch.

In late July 1940, the 48 original paratroopers, 2 officers, and 46 enlisted men began testing for the development of equipment, training, and techniques that would later be used in units dropped into harm’s way. Many of the developments created by this small group are still used to this day. This innovative group of young men performed testing that would claim two lives from their ranks. The platoon took courageous risks required to develop airborne capabilities for the entire American Army.

Among those in the Army, there were not many who knew much about parachutes or paratroopers at the start of WWII. However, at the start of the war, the Germans utilized their fallshirmjager, or paratroopers, in a few operations, stirring some interest in a few officers of the United States Army.

One was Lieutenant William T. Ryder, a 1936 graduate of West Point, who expressed interest in airborne operations long before the Army approved the formation of the Parachute Test Platoon. He studied Soviet and German tactics and training conducted in the late 1930s.

Prior to Ryder’s knowledge of the development of an airborne unit in the U.S. Army, Ryder submitted a number of papers to the Infantry Board covering the use of airborne units in combat.[7]

Ironically, when Lieutenant Ryder showed up with fifteen other officers who volunteered for the opportunity to lead the test platoon for a written exam, he was relieved to find the majority of the test covered articles he personally submitted to the Infantry Board in the past. In forty-five minutes, Ryder completed the two-hour examination and was quickly selected to command the test platoon.[8]

Five of the best Army Air Corps’ parachutists and riggers, led by Warrant Officer Harry “Tug” Wilson, conducted the training for the Parachute Test Platoon. [10] In the first two weeks, their training consisted of tough physical training combined with classes on the basics of the history of the parachute and its theories. Actual jumps were not performed because the platoon did not even have enough parachutes to conduct airborne training.[11] This was truly an outfit that evolved and developed its tactics with each jump.

By the third week, Major William H. Lee, the officer in charge of overseeing the development of the airborne units, sent the platoon to Hightstown, New Jersey. Major Lee discovered that due to the New York City World’s Fair in 1939, there were two 150-foot parachute jump towers his platoon could utilize for training. Later, 250-foot towers were built at Fort Benning to facilitate other paratroopers’ training. The platoon trained in New Jersey for ten days before returning to Georgia to finish their final two weeks of training.[12]

The platoon made great strides, and after its time in New Jersey, the men were in outstanding physical condition and could all pack their own chutes. On the last day of week seven, Lieutenant Ryder announced the completion of the ground phase of their training and the unit would make five jumps the following week.

After his announcement, “Tug” Wilson explained there would be a demonstration where a dummy would be dropped out of an airplane and parachute to the ground.[13] To the horror of every man at the demonstration, the dummy, nicknamed “Oscar,” was “pushed from the aircraft door, and plummeted to its destruction a mere 50 yards distance from the spectating volunteers.”[14] Fortunately for the men, it was only a test dummy.

Lieutenant Ryder, the leader of the platoon, was the first one out of the lead airplane for the inaugural jump, earning him the title of the “First American Paratrooper.”[15] Three more jumps followed the initial test, each one prompted rules and changes to be made to their equipment and techniques. One of these rules included the requirement that every jumper look off into the horizon when standing in the door, rather than looking down. This prevented the soldier from freezing in the doorway, keeping him from slowing down the entire stick’s progress during exit.[16]

The fifth jump the platoon conducted was to be a mass jump for a group of individuals requesting a demonstration of the accomplished work. The audience consisted of General Lynch, Major Lee, General Marshall, and, unannounced, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson. The performance of the jump greatly impressed those in attendance.

The audience witnessed the Parachute Test Platoon conduct the army’s “first airborne tactical operation with well-drilled precision.”[17] As a result of the platoon’s successes, the U.S. Army formed the first parachute battalion. By order of the War Department, on October 1st, 1940, the 501stParachute Infantry Battalion officially activated at Fort Benning.[18]

It took guts to volunteer to be a member of an Airborne unit, not just in combat, but in training as well. The Parachute Test Platoon represented some of the finest America had to offer. They were courageous individuals willing to pay the ultimate price for a military experiment that, at the time, did not even involve combat. They volunteered to help create an asset the Army deemed necessary to fight and win our nation’s wars.

Two short years later, rapidly promoted Major General William C. Lee, dubbed the “Father of American Airborne,” described these pioneers as “the fountainhead of the mighty airborne forces that wrote such glorious pages in the history of World War II.”[19] The Parachute Test Platoon paved the way for many others. Like those original, brave forty-eight, they volunteered to assume additional risk by joining the Airborne Paratroopers and jump out of an airplane, in training and eventually combat.

_____

[1] Edward M.Flanagan, AIRBORNE: A Combat History of American Airborne Forces, Presidio Press, 2002), 5.

[2] Ibid., 7.

[3] Bennett M. Guthrie, Three Winds of Death, (Stillwater: New Forums Press, 2000), 3.

[4] Edward M.Flanagan, Corregidor: The Rock Force Assault, (Novato, Presidio Press, 1997), 101.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Flanagan, AIRBORNE, 201.

[7] Flanagan, AIRBORNE, 10.

[8] Gerard M. Devlin, PARATROOPER!: The Saga Of U.S. Army And Marine Parachute And Glider Combat Troops During World War II, (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1979), 51.

[9] US Airborne[database online], (accessed 12 April 2005); available from

http://homeusers.brutele.be/sgteagle/welcometothealliedairborneheadquarters_usairborne.htm.

[10] Devlin, 53.

[11] John C. Andrews, Airborne Album: Volume One: Parachute Test Platoon To Normandy, (Williamstown: Phillips Publications, 1982), 4.

[12] Flanagan, 12.

[13] Devlin, 60.

[14] Andrews, 4.

[15] Andrews, 5.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Flanagan, AIRBORNE, 12.

[18] Ibid., 13.

[19] James M. Gavin, Airborne Warfare, (Washington: Infantry Journal Press, 1947), viii.

___________________

This first appeared in The Havok Journal on June 2, 2019.

Mike Kelvington grew up in Akron, Ohio. He is an Infantry Officer in the U.S. Army with experience in special operations, counterterrorism, and counterinsurgency operations over twelve deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, including with the 75th Ranger Regiment. He’s been awarded the Bronze Star Medal with Valor and two Purple Hearts for wounds sustained in combat. He is a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, a Downing Scholar, and holds master’s degrees from both Princeton and Liberty Universities. The views expressed on this website are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army or DoD.

Gettyburg