Category: Soldiering

CCR-Fortunate Son.

Just before Christmas, the US Marine Corps held their 248th Birthday Ball in a hotel in London. It was a lavish evening, with medals galore on display, dinner and dancing. But the highlight of the night’s revelry was a nine-minute video. Set to a soundtrack of Future Warrior by Audiomachine, it began with a thrilling montage: of ships steaming through choppy waters, planes doing death-defying loops, helicopters buzzing low over hostile territory and lots and lots of guns, fire and explosions. “Si Vis Pacem Para Bellum” flashed up on the screen. “If you desire peace, prepare for war.”

“Even I was on the edge of my seat,” says one British Army officer who was there. “I thought, ‘I want to join the US Marine Corps right now’.” That, he adds, “is the s— we need.”

In 2022, the US Marine Corps stood at 174,577 troops, with another 32,599 on reserve. In 2020, the Corps received 358,240 applications and accepted just 38,800 of them. Its annual budget is roughly $53.2 billion (£42.1 billion); US defence spending as a whole stands at $877 billion. It’s an unholy sum, and one that throws the state of the British Forces into stark comparison.

That British Army officer is one of just 75,983 regular full-time personnel in the country, with 28,284 reservists backing them up; the lowest numbers since the Napoleonic wars – although the Army nevertheless has the largest number of personnel of all three Armed Forces. Recruiters signed up just 5,560 regular soldiers last year – well below the target of 8,200 – and the outsourcing recruitment contractor, Capita, has admitted it will probably miss this year’s target of 9,813 by a third. Reports suggest that, at the current rate of striking, the British Army will field fewer than 70,000 soldiers within two years.

Britain might be the sixth largest spender on defence in the world (the figure currently stands at £45.9 billion), but a National Audit Office report into the Ministry of Defence’s (MoD) Equipment Plan found that the Army was £12 billion short of the funding required to meet the full demands of last year’s Integrated Review Refresh. The gaps are obvious, and sometimes embarrassing. The 155th Artillery Regiment currently has no guns – we gave them all to Ukraine, along with most of the ammunition needed to fire them. Our 240 or so Challenger tanks date largely to the 1980s and 1990s; the Army has an upgraded version on order, but will only have 18 of them by November 2027 and the full complement of 148 won’t arrive until the end of 2030. There’s not enough money for basic weaponry, let alone to produce a fancy video showing hordes of soldiers blowing stuff up with it.

Little wonder, perhaps, that earlier this week, senior US generals declared Britain to be no longer a top-level fighting force. And even more alarming that the current state of the world may demand us to up our game within fairly short order. So where’s it all gone wrong? And how can we fix it?

‘Start thinking soldier’

Ask your average soldier why he signed up, and a significant majority – if they’re honest – will say they’re in it for the drama, danger and excitement. Or, as one Army officer puts it bluntly, “they want a scrap, and to be able to bayonet someone in the face.”

In this century, the high point of British Army recruitment was 2003, when 16,690 people signed up to fight for Queen and country – just under the previous peak of 16,963 in 1999. At the time, there were plenty of opportunities to fight. In March that year, British troops joined the Americans in invading Iraq, overthrowing Saddam Hussein and occupying the country after a month of fighting that would grow into a conflict of six more years. At the same time, Britain’s Army was also deployed in Afghanistan following the 9/11 attacks. Young men and women signed up in their thousands: average Army recruitment throughout the 2000s was 14,459 per year.

The MoD spent heavily to recruit during those war-filled years: £20.5 million in 2002-03, £20.3 million in 2003-04 and a whopping £33.2 million in 2004-05. Reflecting the difficulties of attracting recruits to the infantry, in 2006 a special infantry recruitment campaign was run at a cost of £5.25 million. Soldiers were harvested from estates in the likes of Glasgow and Liverpool, where the Army offered them a way out of what could otherwise be a pretty tough life: 24 per cent of all Army applicants in 2003-04 were unemployed for a significant period before applying. There was adventure on offer, yes, but also the promise of engagement with an enemy force, and a clear moral divide between them and us. Like the recruitment posters of a century before, the harsh reality of war – the fight, but also the potential sacrifice – was not shied away from. As a recruitment poster from 1934 put it: “Members of the Armed Forces need to be capable of dealing with death and disaster on a daily basis.” The same was true once again. Plus, of course, the chance to bayonet someone in the face.

Fast forward to 2010, however, and things looked rather different. The war in Iraq was winding down. Troop numbers had reached their peak in Afghanistan, at around 10,000, but the nation was growing weary of this long, unwinnable war, especially as the number of fatalities had also peaked; over 100 personnel were killed between 2009 and 2010. Grappling with the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the coalition government was embarking on austerity measures, and in the 2010 defence review, under Liam Fox, the then defence secretary, it was announced that there would be a major cutting back. The Army would shrink from just over 100,000 soldiers to 82,000 by 2020, and would get smaller still by 2025.

“Start thinking soldier” proclaimed a 2010 recruitment video – still set in the desert of Afghanistan but notable for an absence of tanks, helicopters or additional manpower. “Would you mortar them, bug out or engage?” was the question asked of the potential recruit. It’s difficult not to wonder whether the MoD might have been asking itself the same questions. “That was in theory when they [the government] wanted to prioritise equipment, but doing that within the defence budget meant having to make savings somewhere else,” recalls Gen Lord Richard Dannatt, who handed over as head of the Army in 2009. Those savings, he points out, therefore had to be in manpower, “and most of the manpower is in the Army”. By 2012, Army numbers had fallen to under 100,000 and retention was also dropping, with the numbers leaving jumping from 11,500 in 2011 to 13,200 in 2012.

That was also the year that the Army signed a 10-year recruitment contract with the outsourcing giant Capita. Prior to this, recruitment had been carried out by specific teams within military units. Walk into a recruiting office anywhere across the country and you could have had a face-to-face conversation with a soldier, sailor or airman, and be starting basic training within weeks. But with the axe of redundancy swinging, the MoD needed soldiers back in their day jobs.

The Army said the deal with Capita would release over 1,000 soldiers back to the front line, and deliver hundreds of millions of pounds in benefits to the Forces. But the new arrangement was beset with problems from the outset, from technical difficulties with the new online recruitment system to interminable waits after signing up. Auditors found that, in the first six months of 2018-19, it took up to 321 days for new recruits to get from starting an application to beginning basic training; in 2017-18, nearly half – 47 per cent – of applicants dropped out voluntarily, with the delays believed to be a significant factor. The Army estimates there were 13,000 fewer applications between November 2017 and March 2018 than in the same period the preceding year.

The hope at the time was that the Army Reserve would grow to make up the shortfall. But there were manifest problems with this approach: first, a lack of a clearly defined purpose for reservist troops, second, a pay rate that for many didn’t seem worth it for the disruption to their everyday lives and, finally, the same lack of investment in recruitment that beset the regular Army. A 2013 White Paper under Philip Hammond, who by then had taken over from Liam Fox as the defence secretary, proposed military pensions and healthcare benefits for reservists, as well as increased pay, in a £1.8 billion bid to drive up numbers from 20,000 to 30,000 by 2018, at which point the reserves also saw a name change from the Territorial Army to the Army Reserves. But at the same time, some 26 reservist bases of a total of 334 closed down. As former regular and reservist soldier John O’Brien wrote to The Telegraph recently, “these centres served as a vital gateway, introducing young people to military life. The effort of travel within a rural county puts possible recruits off.”

Things haven’t improved much since. The number of reserve bases is now down to less than 50, and, while reservist numbers have increased marginally since 2012, at around 1.2 per cent – despite the MoD signing a further two-year recruiting contract with Capita last June, there was a 35 per cent decrease in people joining the Reserves between 2021 and 2022. The following year, 5,580 reservists left and only 3,780 joined. Part of the problem is mindset, says one frustrated Army officer who works regularly with reservists. Fundamentally, he says, “they’re civilians. They have no idea how to behave like ordinary soldiers, and have none of the credibility.” What’s more, with no requirement to actually deploy, their efficacy is perhaps questionable, especially when it takes time to train reservists up to standard. “You can’t train a reservist to use a tank overnight”, points out one officer who has done several stints on the recruitment front.

Aside from the antiquated process, part of the problem in its recruiting of both regular and reservist forces, says the officer, is that Capita “measures success as people who come through the door, instead of the people who complete the training”. To succeed in getting the right men and women into a position to fight, he says, the system needs “to move from assessments to tests. A test is something you pass or fail. An assessment means someone only needs to attempt it. But to close and kill the enemy, you need to deliver to the standard required, and the standard is a test, not an assessment.”

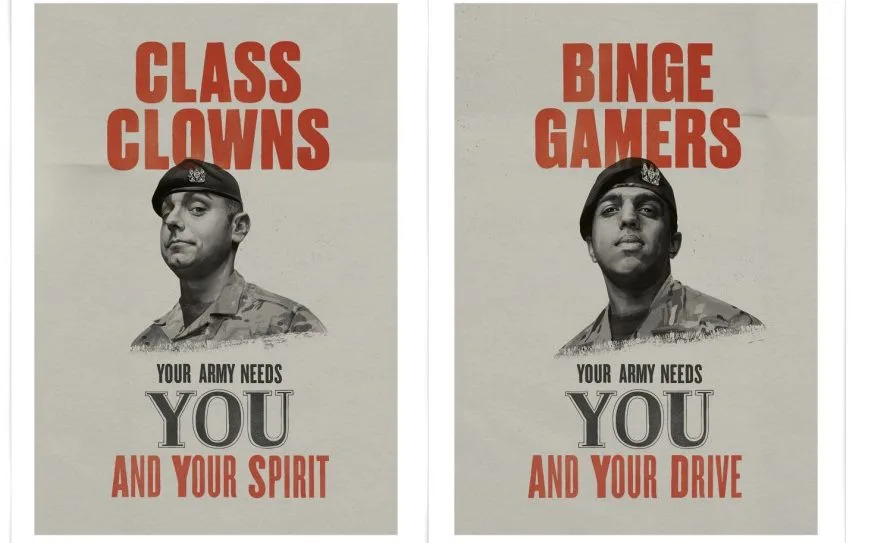

There’s also the issue of who’s being targeted in the first place. In recent years, recruitment campaigns have, in the view of many, “gone soft”. In 2016, military chiefs sought to appeal to a supposedly altruistic Gen Z with reverse psychology. “Don’t join the Army,” its campaign declared; “don’t become a better you.” This was followed by 2017’s “This is Belonging” campaign, telling the stories of soldiers who believed they wouldn’t fit in to demonstrate that all are welcome. In 2019, the “Snowflakes” campaign called on “snowflakes, selfie addicts, class clowns, phone zombies and me, me, me millennials” to join its ranks in a campaign that infuriated not only an older generation but many serving personnel too. In September of last year, it was “You Belong Here”, “to challenge the misconceptions among the 59 per cent of young people who do not believe they would fit in.”

“There’s so much wokery and mixed messaging,” says one former Marines officer. And, while these campaigns may have been successful in attracting those who might not otherwise have thought of a career in the military, the problem is that they have ignored what has always been the Army’s traditional recruiting base: white, working-class boys (and girls) between 16 and 24 who want, as one Army officer puts it, “drama, danger, excitement, reasonable pay and a fight”.

These campaigns, he says, “don’t show tanks or anything blowing up. But my bit of the Army is there to fight and kill the enemy – and we’re not very good at telling people that’s our job.”

‘Armies are not easy to create’

So what now? Europe is teetering on the brink of all-out war. If it breaks out, Britain would have to step up to fulfil its Nato commitment. So do we really need the citizen armies that Gen Sir Patrick Sanders alluded to last week? And what about the kit they would have to fight with?

“If the Government wants to make the Army as effective as it could be, it requires total governmental and political support, sustained investment, and a sense of urgency to do things quickly,” says former brigadier Ben Barry, a land warfare expert at the International Institute for Strategic Studies. He outlines three main priorities: accelerating recruiting, a return to fully collective, large-scale training and a renewed focus on the logistics of weapons procurement. People, says Barry, are key – and, he says, “to be brutally frank, if you want sustained readiness, the high priority has to be the regular Army” – not the Reserves. (It’s sobering to remember that in the first six months of fighting in Ukraine, the Russians took the same number of casualties as the headcount of the entire British Army.) That means improving the offer to attract and keep the good people, from implementing pay review recommendations, to retention bonuses for those serving, to a massive improvement in the standard of living accommodation. “We have to make a better offer to those who might be wanting to join,” agrees Lord Dannatt – and get front-line soldiers back into recruiting offices to attract the brightest and best.

That’s not to say there isn’t a role for reservists, who might also be bolstered by a larger, better and more engaged regular force. Should we introduce some form of national service – that citizen army that Gen Sanders referred to – in the manner of our European counterparts in Sweden, Finland and Norway? Difficult, when military life has become so segregated from its civilian counterpart. As Richard Munday wrote to The Telegraph recently, even “organisations like the National Rifle Association, and events like the King’s Prize at Bisley, are ghosts of their former selves because their objectives have been countered by political decisions that have sought to segregate the military from civilian life, and sporting skill and interest. If we are serious about the need to maintain a credible Armed Forces in the future, we must bridge that divide.”

“Armies are not easy to create”, points out Maj Gen Chip Chapman, a former paratrooper and senior British military adviser. “You need motivated people who will join because they see it as vital for the UK’s interest. The worst thing you could have is people being coerced to join.” Instead, says the Army officer with recruitment experience, “more effort needs to be made to get people who have previously served back in [as reservists] – because it’s experience we’re lacking now.” Another suggestion is for all fit and willing former regular soldiers, numbering some 200,000, to be invited to take part in annual military exercises.

Next is kit, which Britain is woefully lacking: we’re low on guns, we’re low on the ammunition to shoot them, we’re low on tanks and the two aircraft carriers on which the majority of the defence equipment budget was blown in recent years are undeployable as Britain doesn’t have enough sailors to man them. We’re also majorly lacking in layered air defence – the ability to fight off attacks at both short, mid and long range. Recent suggestions that the carrier HMS Elizabeth could be deployed to fight off Houthi attacks in the Red Sea ignores the fact that we are lacking the jets to put on them that would provide the long-range cover.

“The situation could be better,” admits Nick Reynolds, research fellow for land warfare at the Royal United Services Institute. Part of the problem, he says, is that modernisation across the board was delayed by the Helmand campaign, which means everything needed to be brought up to date at once. But, he says, the Ukraine war has highlighted some stark requirements: first, the need to produce and stockpile munitions quickly and on a mass scale; second, to simplify the bureaucratic procurement system, cutting out the cronyism, and third; invest in air defence capability across all ranges. “Unfortunately, we’re now in a position where having sovereign capability and a large workforce with a significant amount of expertise is a very valuable thing – but we allowed that to atrophy,” he says. “We need a more sustainable arms industry, to produce things in-house.”

It would, he says, involve a massive expansion of the UK domestic arms industry – a prospect many might feel uncomfortable at. But doing so could also bring job creation and boost the economy. The question, says Reynolds, is whether – as a country – we are willing to have that conversation with ourselves.

Of course, all of this doesn’t come cheap. The Army has a £44 billion procurement plan over the next 10 years, but, as Gen Sanders has pointed out, just 18 per cent of that money is committed – a dangerous position to be in during an election year. And, says Lord Dannatt, we should mind the lessons of history. In 1935, for example, Britain was spending less than 5 per cent of GDP on defence. When war broke out that figure shot up to 18 per cent, and when the country was fighting for survival in 1940, it went up to 46 per cent. “18 to 46 per cent is the price you pay for disaster,” Lord Dannatt warns. “We have to be prepared to pay the price for deterrents. Even going up to 3 or 4 per cent of GDP would buy us sufficient Armed Forces to be credible within Nato.” Russia is right now spending nearly 40 per cent of its GDP on defence.

The MoD is aware of the problems. Last June saw the publication of the Haythornthwaite Review into Armed Forces incentivisation. Its brutal conclusion was that the current system doesn’t really work for anyone; it proposed a radical overhaul to resolve the tensions between career progression, operational effectiveness and family life. “Future recruitment is a top priority,” said an MoD spokesman, adding that the measurements the Haythornthwaite Review set out, from zig-zag careers where people can leave and re-join the Armed Forces, through to reviews of pay and progression, are being trialled and piloted. In December, meanwhile, more than 400 soldiers were ordered back into recruiting offices in a bid to get more people to enlist. And, said Grant Shapps, the Defence Secretary, in an interview with The Telegraph on Thursday, Army recruitment almost doubled last month alone amid growing fears of a confrontation with Moscow.

But as Britain looks to the future, the official British Army motto might be a salutary reminder. “Be the best”, it proclaims. To do that, it needs commitment, cash and political will. So, what will the recruiting video of 2024 show?

For some unfathomable reason I’ve always had a deep interest in the history of the United States horse soldier, especially from the Indian Wars era of 1866 to 1890. In 1968 there were a few weeks between the end of my summer job and the beginning of my second year in college.

While most of my contemporaries headed for places like Virginia Beach, Myrtle Beach, or points in Florida, I drove from West Virginia to Montana for the sole purpose of seeing what was then called the Custer Battlefield. Now politically correctly called Little Bighorn Battlefield.

While there I walked the ground above the Little Bighorn River to gain a sense of the fight, but when visiting the museum there happened a defining moment in my shooting life. On display were samples of the weapons used by both Indian warrior and cavalryman. Among the 7th cavalry’s items was what we call today a Colt Single Action Army .45 caliber revolver with 71⁄2″-barrel, onepiece walnut grips, and the (misnamed) black-powder frame.

That particular display revolver was by no means in new condition. Instead it was covered with a dark brown patina as would befit a handgun nearly a century old that had been carried much in the outdoors. And I wanted one.

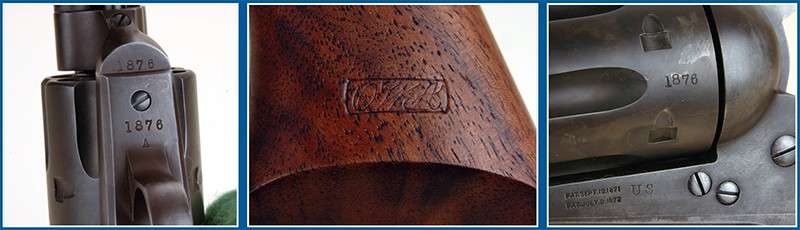

Top-left: Duke was lucky enough to get the serial number “1876” for his USFA Custer Battlefield .45.

The small “A” stands for Ainsworth, the government inspector at the Colt factory at the time the Custer Battle

single actions were manufactured. Middle: Ainsworth also stamped the walnut grips of each SAA

to leave the factory with his own personal cartouche.

Top-right: Note the U.S. stamp on the frame and the serial number also placed on the

cylinder. Both are authentic to Custer Battle era SAA revolvers.

Duke’s Itch

That wasn’t an easy itch to scratch. Colt introduced the Single Action Army and its .45 Colt cartridge in 1873 and the U.S. Army accepted it that same year for cavalry service. In fact, the 7th Cavalry’s 1874 summer expedition to explore the Black Hills area was delayed until the regiment’s new Colt revolvers arrived via railroad from the east.

From 1873 until 1892 the Colt SAA .45 was standard issue for U.S. Army horse soldiers, and it actually remained in their hands for some time after the official adoption of a Colt double-action .38 revolver in the early 1890s. Many were returned to service for duty during the Spanish-American War and the Philippine Insurrection.

The standard Cavalry Colt SAAs were all of a theme. They were issued with 71⁄2″-barrels, one-piece walnut stocks, and color case hardened frame and hammer with the rest of the metal parts blued. Some finish variations are known to exist but in numbers so small as to be curiosities.

It was a simple and rugged handgun as necessary for one intended for horseback carry. During that almost 20-year period when the U.S. Army was buying Colt .45 revolvers, the total numbers purchased were not large. According to A Study of the Colts Single Action Army Revolver by Graham, Kopec, & Moore the government bought only about 37,000 Colt .45s.

What makes original cavalry Colts even more scarce is the fact between 1895 and 1903 the Army rebuilt and altered MOST of the Colt .45s they had in storage. Their barrels were cut to 51⁄2″ and they were stripped down with the parts refinished or replaced as need be. Most were then reassembled from the refurbished parts with no attention to matching serial numbers.

Today collectors commonly call these shortened cavalry Colts “Artillery Models,” but it should be stressed they were not issued only to artillery units after alteration.

The Quest

According to the book mentioned above, most of the Colt .45s that actually saw service with the horse cavalry were among those altered. Many that escaped alteration had been lost or stolen during service. For instance, in the debacle along the Little Bighorn River in 1876, the 7th Cavalry lost well over 200 SAAs to the Sioux and Cheyenne victors.

Also quite often deserters took their revolvers with them. And too, it’s well documented that some troopers (making $13 a month) sold their new pattern sidearm to civilians at scalper prices of up to $50 and then gladly paid the Army the $13 or so they were docked for “losing” them.

Back to my quest for a U.S. Colt SAA. So impressed was I with Montana on that 1968 trip I returned every summer break to work there, and then became a permanent resident after graduation in 1972. During those youthful years a genuine Cavalry Colt was far out of my budget.

So I determined to build a facsimile. In the spring of 1975 when visiting family back east I wandered into a gun store in Prestonsburg, Kentucky. That store had a rather ratty looking Colt SAA .38-40, but what attracted me to it was the fact that it had the black-powder frame, and the triggerguard was marked with a tiny “.44 CF”. That latter point told me that the gun wasn’t original, so I would do it no great harm by building it into my long desired Cavalry Colt.

Back in Montana I ordered a 71⁄2″ .45 Colt barrel and cylinder from Christy Gun Works of California, and then had a gunsmith install them in the old SAA frame. An atrocious-looking set of onepiece walnut grips were cobbled together for it, and I joyfully set about shooting my cavalry Colt — with light .45 Colt loads in deference to its old frame. My initial impression was, “Boy, this long barrel must make those loads shoot harder. This gun kicks!”

Regardless, it was accurate and I fired several hundred rounds through it. Then one day I decided to slug the barrel. The resulting slug measured .429″! I slugged it again with the same results. Christy Gun Works had sent me a .45 Colt cylinder but a .44 caliber barrel. To say I felt stupid about not noticing it was an understatement, but I took solace from the fact that my gunsmith hadn’t seen it either. Duh!

There’s Still Hope

In 1976 Colt introduced the Single Action Army for the third time, and since I had been working lots of overtime on a road maintenance crew in Yellowstone National Park, I ordered a .45 with 7″ barrel. What a disappointment! It was poorly finished and assembled so badly none of the seams where grip frame and main frame came together mated evenly. It’s trigger guard even came with a crack when new-in-box. I soon sold that .45. And duh again!

By 1984 I was a full time gunwriter and beginning to focus much of my attention on Colt SAAs, so I was aware Colt had improved quality somewhat and was also again offering the black-powder frame. However, this was a time when they would accept no orders for the SAA unless they came with rather costly “embellishments.” That meant the buyer had to spring for additional things like presentation boxes, engraving, ivory grips, etc. so I sprang.

My order was for a 71⁄2″-barreled .45 with fancy box and ivory grips. As soon as it arrived the ivory grips were stashed away and I had a gunsmith fit it with plain walnut one-piece stocks. He was even able to put a facsimile of an inspector’s cartouche on the left grip panel just as the original U.S. Colts had. I was fairly happy with that gun, and even carried it in 1986 on a horseback ride that traced the 7th Cavalry’s path from where they spent the night of June 24th/25th 1876 right up to the battle monument near where Custer’s body was found after the fight.

Still Not Right

However, I still wasn’t completely satisfied in my quest for a “Cavalry Colt.” Mine didn’t have the “U.S.” stamp on the left side of the frame, its hammer wasn’t color case-hardened, and its sights weren’t the old-style fine ones of early Colts. Surely, that was nitpicking, but I was getting more affluent and could afford to be picky.

By that time I perhaps could have even bought an original Cavalry Colt but that would have wiped out my ever-stressed “gunmoney fund.” Besides, I was a shooter more than a collector and even then was smart enough to know doing much shooting with something as valuable as a genuine U.S. marked Colt SAA wasn’t real bright.

Back in 1975 Colt had brought out a limited run of what I felt would be the perfect “Cavalry Colt” for me. Those were the Peacemaker Centennials in .44-40 and .45 Colt calibers. The ones chambered for the latter round were precise duplicates of U.S. Cavalry issue Colt SAAs — right down to tiny details such as the sights, markings and grips. The only fly in the ointment was that as commemoratives they had the logo “1873-1973” on the right side of their barrels. I could live with that.

The problem was in finding one. Colt built only 2,002 of them so they weren’t just languishing on dealer’s shelves. Indeed once in the late 1970s I even saw one at a gun store, and drove the 80 miles home to gather money only to return to find someone else had already bought it.

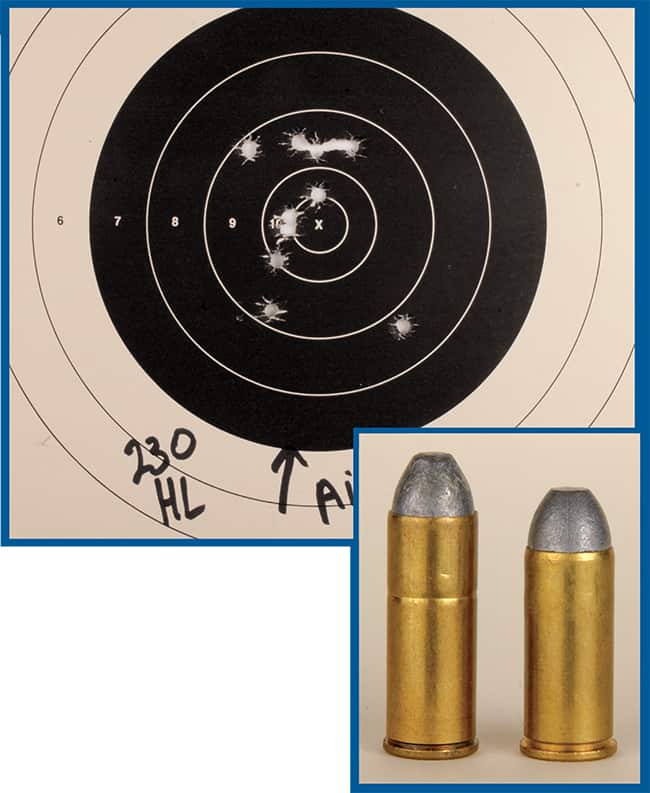

Above: Using Duke’s favorite .45 S&W handload his USFA Custer Battlefield revolver grouped

center at 25 yards with a six o’clock hold. Shooting was done from a standing position with one hand as was

taught to cavalrymen of the era. Right: Although the Colt Single Action Army handguns

shipped to the U.S. Army between 1873 and 1892 were chambered for the .45 Colt cartridge,

during most of its service life troops were issued with

the shorter .45 S&W “Schofield” cartridge.

Patience Wanes

Not until 1993 did I see another Peacemaker Centennial .45 for sale, and that was when a fellow walked up to my gun show table and set a brand new one down and said, “You interested in that?” Brother was I ever! Without quibbling I paid him his asking price, and after 25 years my Cavalry Colt itch was finally getting scratched. That big Colt .45 became one of my favorites; so much so it was one of the Colt revolvers shown on the cover of my first book, Shooting Colt Single Actions. I made such a fuss about it in print that in the year 2000 another fellow offered me a second one, so now I have a matched pair.

There’s More?

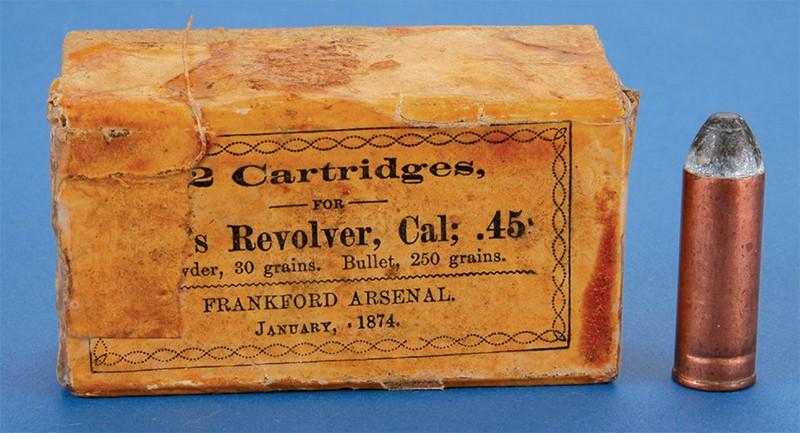

In cowboy-action matches I shoot them exclusively with black-powder loads, while doing my plinking and practicing at home with smokeless loads. Almost always I put those loads in .45 S&W “Schofield” brass, which is actually more authentic to the Indian Wars era than you might think. The Colt SAA was introduced in .45 Colt caliber, but by August 1874 the U.S. Army informed the government’s Frankford Arsenal to only build the shorter .45 S&W cartridge, which they did for the next 18 years.

Most cavalry units carried the shorter .45 S&W round in their SAAs, but modern archaeology has shown that Custer’s 7th Cavalrymen used the longer cartridges at the Little Bighorn. Anyway the difference in power wasn’t great. The government loaded the full-length .45s with 250-grain bullets over 30 grains of black powder. The shorter .45 S&W used 230-grain bullets and 28 grains of black powder.

At this point a normal person would be satisfied. But, what sort of “normal” person would become a gunwriter anyway? At SHOT Show 2005, I was visiting in the United States Firearms Manufacturing Company’s booth with their president, Doug Donnelly. My eyes fell on a Cavalry Colt in the display, and I had to ask, “Doug, what’s with that old Cavalry Colt mixed in with all your new guns?” His answer amazed me. “That’s one of ours” he said, “We’re offering a Custer Battlefield model, with antique finish.”

That did it. I ordered one on the spot, and in doing so I learned the buyer could even specify his own serial number as long as the number was in the range inspected by U.S. Army Ordnance Sub-Inspector Orville W. Ainsworth. That man inspected and stamped Colt SAAs at the factory in the era when they could have actually been issued to the 7th Cavalry prior to their fight at the Little Bighorn. Eagerly, I asked, “Has anyone taken the number 1876?” No they had not, and I got it!

At Last

A few days before this writing, my U.S. Firearms Custer Battlefield single action arrived. It’s all I had ever hoped for: the antique finish is dingy just like that original Colt SAA still on display at the battlefield’s museum. Sights, firing pin, ejector rod head and grips are perfect renditions of those items found on original “Cavalry Colts.” The “A” inspector’s stampings are precisely where they are supposed to be, as is the cartouche on the left side of the walnut grip, and the U.S. stamp on the frame’s left side.

Furthermore, it has that fantastic quality in regards to fit and lock-up the U.S. Firearms Company has gained such a positive reputation for. My only complaint about it is the bevels on the cylinder’s flutes are not quite as pronounced as with original 1870s vintage Colt SAAs.

Now at this point I’m supposed to describe just how tightly their test guns group. I’m not going to because I have never fired my USFA Custer Battlefield .45 for accuracy from a rest. There’s no reason since I intend to shoot it primarily as U.S. Cavalrymen did. That was with one hand because the other was needed for the horse’s reins.

Also it will almost always be fired with .45 S&W “Schofield” loads as most U.S. Colt SAAs were fired. Black Hills Ammunition makes a 230-grain .45 S&W factory load and I also handload 230-grain bullets in the .45 S&W cases over 5.3 grains of Hodgdon HP38. Both loads give about 730 to 750 fps from my USFA Custer Battlefield .45, and that’s precisely the power level given by original military loads. However, I should say that from 25 yards the USFA .45 prints groups about 4″ above point of aim and centered with my handloads, and about 2″ high and still centered with the Black Hills factory load. Remember that shooting was done from a one 2 handed standing position.

Interest in the horse cavalry of old has been a strong influence on my life. It even helped determine where I live and the types of guns I shoot. My onagain/off-again quest for a “Cavalry Colt” is over now, but it was sure fun during the nigh-on 40 years it lasted.

Veterans are mostly proud of their service. And rightfully so, it’s no small thing to take the leap into the military and all that it entails. But there are some veterans who, well, they’re like that one 50-year-old dude for whom high school was the highlight of his entire life and who references every situation back to “the good old days.” Like that, but, you know, with guns.

Because of this, we all know those service members and veterans who so prominently display photos of themselves on social media in uniform that all we can muster is a heavy eye roll or an “unfollow.” We get it, you served, thanks for the daily reminder. Not sure how Arbor Day is all about veterans, but somehow you made it out to be. You know, that kind of veteran. To some extent, we’re all guilty of this in some capacity. Because out of the millions of photos out there, they can all be boiled down to fall into about seven distinct categories of obnoxiousness.

1. The Basic Trainee

Imgur/tinychampion

This photo gets whipped out whenever a vet feels nostalgic, and it’s often accompanied by some remark such as, “It was harder at back in than it is for these soft kids today who get coddled!” It’s also a popular photo for those individuals for whom basic training was the only point in their career, because they didn’t really make it any further. The poster bears some risk in doing this because if they’re discovered they are apt to be covered in a deluge of ridicule.

2. The Mirror Selfie

Imgur/kcool951

This one is firmly the property of the younger generation these days. And with all mirror selfies, we have to say: Please police up your backgrounds before you post these things. We can clearly see the pile of Bud cans behind you and — worse — your messy pile of moto t-shirts. We get it, you love your job, but we don’t need a daily reminder of what you in uniform and your shower curtain look like. Give it a few years until you are managing troops like yourself and you’ll be singing a different tune.

3. The ‘Look How Responsible I Am’ One

U.S. Navy/Capt. Ronald L. Ravelo

Clad in dress uniform or serviceable camo, maybe even cracking a clean-cut smile, we can see that you’re a responsible service member — probably an officer. Your feed is full of positive stories about the military and your family. Frankly, boring, but we’re glad you’re around to provide order and point out uniform violations online.

4. The DGAF

This one is a bit more nuanced, because it can be divided into two categories: the DGAF (don’t give a fuck) military and the DGAF ETS/EAS’d. The DGAF military is usually a bunch of grubby troops out in the field with all manner of uniform violations, exercising their ability to cram a vast quantity of tobacco products into one shot. These photos often include some kind of animal or mascot. Apparently there are bonus points if you incorporate one of many stages of inebriation and the vagaries of uniform adjustment that come with it. The DGAF ETS/EAS’d veteran demonstrates how quickly one can lose one’s military fitness after leaving the service while still letting everyone know that you served. It takes skill, really.

5. The Shooter

National Guard

This variant shows the service member or veteran in some sort of a shooting pose: staring grimly down the barrel of a rifle, putting lead downrange with a machine gun, or dramatically going toe-to-toe with a 25-meter target with a 9mm handgun. Added bonus points if there’s a blank firing adapter attached so that we know that you’re a real hardcore killer. And for those of you who tried to pose to make it look like you’re engaged in a brutal firefight with Tommy Talib, it begs the question: Who do you expect us to believe it was that took the picture? Now go think about what you’ve done.

6. The Band of Brothers/Sisters Shot

Imgur/MrMacy

One of the most common, this one shows the veteran posed with a group of their buddies in front of their vehicle/track/combat outpost/helo/vessel/aircraft. Usually there’s an American flag somewhere in the picture. It’s often a phone photo of a hardcopy photo to get that vintage feel. There’s bound to be a mix of those who really want to take this seriously and are at parade rest or at responsible low ready, and those who really don’t care and who are throwing up all manner of obscene gestures.

7. The Operator

U.S. Army

And the most common of all: The guy standing in front of a desolate backdrop, or one of Saddam’s many palaces, holding a weapon. By the obligatory law of veteran social media, the weapon has to be held at a 45-degree angle, either at the low ready or in the air Rambo-style. This one lets everyone know that you’re a hardcore combat killer since you also seem to be wearing half of Ranger Joe’s tacticool product line. The zip ties are a nice touch, what with all the detainees that your convoy protection team will be processing. Again, bonus points for a blank firing adapter. Same for a belt of linked ammo draped artfully across your shoulders, because as we all know, ammunition always feeds better if it’s covered in dirt.