Well I was impressed especially since I was one lousy soldier when it came to drill & ceremony like this. Seeing as I would rather be at the NTC than do this & I HATED NTC. Grumpy

Category: Soldiering

New Delhi, India

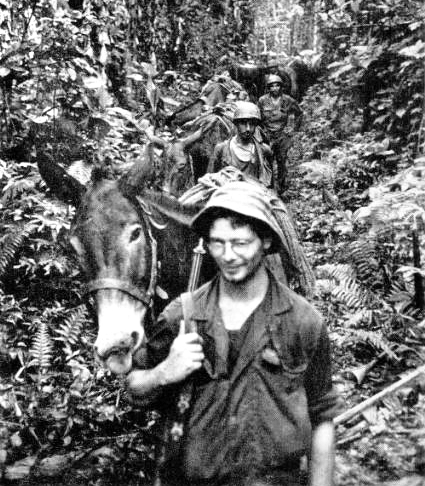

If army mules ever get to swapping barnyard yarns after this war, the mules of Merrill’s Marauders should outbray all the rest. For early this year those long-eared veterans of the Burma jungle slogged their way for four months straight over 700 miles of muddy trail and precipitous mountain tracks on the march to Myitkyina. Without those heavy-laden pack animals from Missouri, Texas and Tennessee, Merrill’s fighting foot soldiers might never have captured that strategic Japanese airfield for General Stilwell’s forces.

The Marauder mules were activated at Fort Bliss, Texas. After two months at sea they arrived in Calcutta, slightly underweight but none the worse for having weathered a heavy seven-day storm and two unsuccesful torpedo attacks.

The mules had scarcely got their land legs back when they were sent on the trek to Myitkyina. On that long jungle march each carried, in addition to 96 pounds of saddle, 200 pounds of essential equipment – light and heavy mortars, 75-mm pack artillery, heavy and light machine guns, ammunition, radio equipment, food, medical supplies.

Among the Marauders only about 150 were trained mule skinners. Thus, on the eve of the march to Myitkyina, each of several hundred former clerks, salesmen, factory workers and garage hands suddenly found himself in charge of one of Nature’s strangest four-footed creatures – the sterile, stubborn but almost lovable mule.

Many of the Marauders possessed as little animal lore as the British officer who, on receiving a consihment of sleek, fat-bellied mules, wrote that the mules looked all right, except that half the damn things were in foal. Once, at the end of a long day, General Merrill said to a disheveled, weary mule skinner who was laboriously rubbing down his mule, “You seem to take good care of your mule. Had much experience in the States?”

“Well, sir,” said the soldier, “I saw a mule once, in Brooklyn, hitched to an ice wagon.”

To train a man to be a mule skinner is no easy task. It is so difficult, in fact, that General Merrill said after Myitkyina had been reached, “Next time give me mule skinners and I’ll make doughboys out of them instead of trying to turn doughboys into mule skinners.”

Many of Merrill’s men, however, became passable mule skinners. They learned how to pack a mule so that his load was evenly balanced.

| IN THE BURMA JUNGLE, A MULE BECOMES U.S. FOOT SOLDIER’S BEST FRIEND |

And, camping at night, they always groomed, watered and fed their mules before finally bedding down near their charges.

The mules soon developed a fine instinct for jungle and mountain trails. But occasionally one would slip or fall exhausted from a precipitous path. Then the mule skinners would climb laboriously, often dangerously, down the mountainside and hack out steps by which the mule could climb up to regain the path.

Basic cavalry training had made them “bell-crazy,” for they had learned to drill by following a mare with a bell. It was, of course, necessary in the jungles for mules to disperse under attack and to act under the direction of each individual mule skinner. At first they insisted on following each other. If they were dispersed they balked and brayed. Later they showed excellent battle discipline, separating quickly and quietly.

At Walawbum, however, where a Marauder unit found itself greatly outnumbered by Japanese, the mules took it into their heads to bray lustily. Says General Merrill, “The Japanese were evidently fooled by the mules. They thought we had them greatly outnumbered and they didn’t dare attack, thanks to those mules.”

At Nphum Ga, where the Marauders were surrounded by a superior force for over two weeks, many mules were lost from starvation, thirst and artillery fire (a mule can’t get in a foxhole). The Japanese controlled the only water hole. Men were wounded trying to take animals to water. Eventually they had to send the mules to the water hole by themselves, unharnessed, since the Japanese could catch the harnessed mules. One mule was sent to the water hole at night to draw Japanese fire, so that Japanese positions could be located for a forthcoming attack. Later, when the action was succesful, the mule was found dead, with a huge steak cut away from one haunch. At Nphum Ga some of Merrill’s Marauders were killed while caring for and burying their mules.

Each mule skinner has his own mule whom he names Jake or Puss or Shorty but whom he usually calls “you ——” or “— — – —–.” These are terms of endearment for one’s own mule, but dangerous cursing when applied to another’s, Listening to this almost endless stream of profanity directed muleward, a novice is apt to inquire sympathetically, “What’s the matter with your mule?” The invariable answer is, “There’s not a damn thing the matter with it, it’s the best damn mule in the jungle.”

A mule always has a reason

Any good Marauder mule skinner defends mules vigorously against any of the usual charges made against them. A mule is not stubborn, he is practical. A mule doesn’t want to be disagreeable unless he has to. He just sensibly follows the line of least resistance. If he balks or kicks, he has a reason. Caught in a tight spot, a mule never kicks himself to death or flounders as a horse often does. He sensibly waits for help. A mule doesn’t fret and give way to nerves as men and horses do, he makes the beat of things. He is well-behaved under fire and bombing.

He never gets shell shock. He has much more endurance than a horse and, unlike the horse, he has too much sense to overeat and overdrink. A mule is in fact, say Merrill’s Marauders, a pretty savvy creature all round. As Colonel R.W. Mohri, the Burma mules’ vet, puts it, “A mule’s every bit as intelligent as a human being. Probably more so. So to get along with him you need to have, if possible, as much sense as the mule.”

A mule is as brave as he is intelligent, and the only thing that frightens him in the jungle is the elephant. The elephants fortunately are likewise terrified of mules. In encounters, both run away at top speed, filling the sir with their trumpeting and braying.

Marauder mules have proved themselves first-class “jungle wallahs.” After months of long, exhausting marches through mud, across rivers, up and down mountains, in thickest jungle growth, harassed by leeches and flies, shrapnel and bullets, most of them were put to work when they finally arrived at Myitkyina carrying supplies from the planes coming in to the airfield. Many are there now and eventually, instead of marching back out, they will be turned over to Chinese troops. Some days these mules from Missouri, Texas and Tennessee will undoubtedly find themselves marching to China over the Burma Road.

One out of all the numerous mule yarns has become a favorite with the Marauders, who are all volunteers. A mule skinner, exhausted by continual arguments with his mule, which consistently refused to climb mountains, cross rivers or otherwise overexert himself, finally lost his temper when the mule lay down and refused to budge. “Get up, you — — – —–,” snarled the driver. “You’re a volunteer for this mission, too.”

What would you do if you came into some serious money? I don’t mean you inherited a couple thousand bucks from crazy great-aunt Mildred. I mean what would you do if you were suddenly just filthy rich?

We’ve all pondered it. Last week some unidentified person in California won more than $2 billion in the Powerball lottery. Before that guy walked away with all that cash I admit that I entertained myself in quiet moments imagining what I’d do with such a windfall. I’d bless my friends and family, to be sure, but I’d also buy an island along with my own vintage Spitfire. Anyway, considering I have never bought a lottery ticket, the chances of my winning the lottery are pretty small. Of course, the odds wouldn’t change a whole lot had I actually bought a lottery ticket, either. That’s honestly the point.

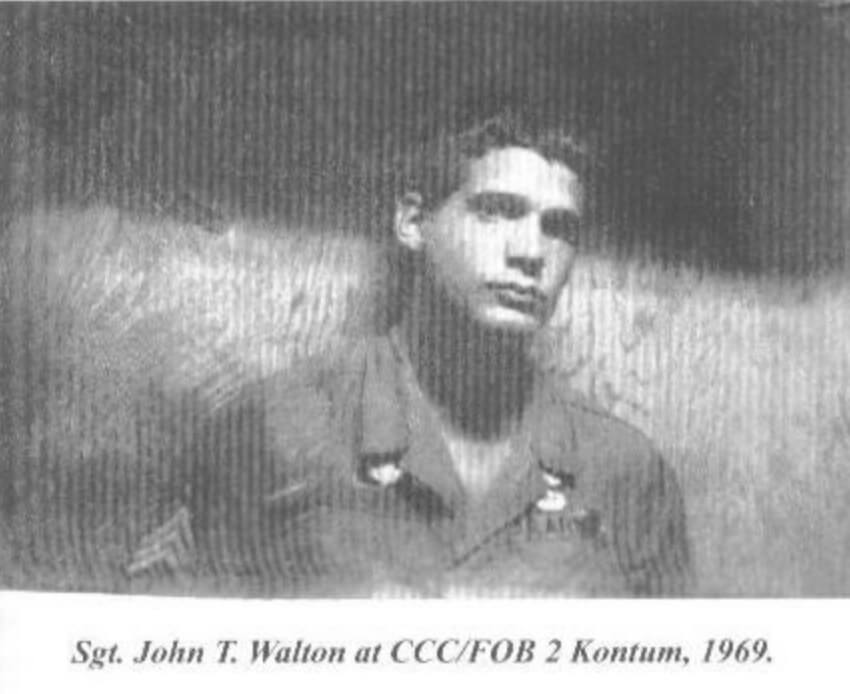

Some folks are born into money. Others work really hard or are just plain lucky. As the second son of a dime store owner from Arkansas named Sam, John Walton wore his wealth well. In great part, this is likely because young John had known some proper suffering before he got rich. Much of that hard experience he got while in uniform.

John Walton was the second of four kids born to Sam and Helen Walton. In High School, John was a dichotomy. He was a star football player who also enjoyed playing the flute. After graduating from Bentonville High School in Bentonville, Arkansas, he attended the College of Wooster in Wooster, Ohio. In 1968 he dropped out of school so he could better his skills as a flutist. After reading about the Tet Offensive, John Walton enlisted in the Army.

John Walton had good genes and a killer work ethic. In short order, he was a fully qualified Special Forces medic assigned to the Studies and Observations Group in Vietnam. He saw combat in the A Shau Valley as well as in Laos and Cambodia. During his cross-border forays, he was assigned to Spike Team Louisiana operating out of Forward Operating Base (FOB) 1 in Phu Bai. These stone-cold SF warriors would insert via helicopter to monitor movement along the Ho Chi Minh trail and call in air support to interdict enemy formations as the opportunities arose. Such stuff required simply legendary bravery and epic fieldcraft.

August 3, 1968, was a Saturday. SP4 Walton was deep in the suck in the A Shau Valley alongside five other members of his recon team. His unit was compromised and attacked by a numerically superior NVA force. In short order, the team was surrounded and immobilized. With the incoming fire now utterly overwhelming, the team leader called a Prairie Fire mission for any nearby strike assets. Prairie Fire meant that an SF team was about to get annihilated. Anything with a gun or a bomb was expected to answer the call.

The NVA knew that Americans had access to overwhelming firepower and that the key to success was to get in close and stay there. With automatic weapons fire and grenades raking their position, the spike team leader reluctantly called in an A-1 Skyraider to drop on their own position. The strike killed one member of the team, severely wounded the team leader, and blew the radio operator’s right leg off. To make things worse an NVA soldier got a clear line of sight and shot the fourth Green Beret four times with his AK-47 before being killed by John Walton, the only team member still intact.

John was an SF medic, and those guys could do some amazing medicine in the field. SP4 Walton assumed command of the team and went to work stabilizing the wounded while also manning the radio. Amidst everything else, SP4 Walton continued working the Tac Air, calling down fire on the tenacious NVA troops.

Three rescue helicopters answered the call. The first onsite was an antiquated H-34 Kingbee flown by a South Vietnamese pilot named CPT Thinh Dinh. The H-34 was, by the standards of the day, a piece of crap. Powered by a reciprocating radial engine rather than the jet turbines that drove American aircraft like the UH-1 Huey and OH-6 Loach, the H-34 was woefully underpowered, particularly in the thick hot environment of the A Shau. Despite suffocating ground fire, CPT Thinh bravely brought his aircraft into a nearby clearing and set it there as enemy rounds chewed through the airframe.

SP4 Walton dragged his teammates out to the aircraft one at a time until the antiquated helicopter was as heavy as it could be and still fly. Walton, for his part, would have to wait on the next bird. As soon as the young medic was clear CPT Thinh lifted off and nosed over toward the nearest field hospital. Then he heard over the radio that the next two rescue aircraft had turned away due to the overwhelming volume of ground fire. With that, CPT Thinh torqued his overloaded Kingbee around and headed back into hell.

Thinh landed his fat aircraft in the same spot and stayed there until Walton could get on board. However, now the old helo couldn’t hover. With enemy automatic weapons fire chewing the aircraft to pieces, the brave South Vietnamese pilot got the aircraft teetering up on its forward landing gear struts. In this awkward configuration, he pivoted the machine around until it faced a nearby draw. He then allowed the helicopter to roll downhill until he could take advantage of effective translational lift and actually break ground and clear the jungle. In this sordid state, CPT Thinh nursed his stricken aircraft to safety, saving Walton’s life in the process. Once the dust settled SP4 Walton was awarded the Silver Star for his courageous actions in saving his team from certain death.

In the aftermath of this particular mission, Walton confided to his friends that, if he lived to get home, he planned to buy a motorcycle and travel. Along the way, he hoped to learn to fly and explore Mexico, Central, and South America. For many to most folks, such stuff would never get past the dream phase. However, this was Sam Walton’s son. As we discussed before, he had good genes.

While John was in Vietnam, his father Sam had been busy. By the end of 1967, he had 24 Walmart stores operating in Arkansas. The following year he opened his first stores in Missouri and Oklahoma. By 1975 Walton had 125 stores and 7,500 associates with total sales of $340.3 million.

Soon after John got home he was flying for his father scouting out new locations for Walmart stores. In short order, he left Walmart to work six months out of each year as a crop duster. The rest of the time was spent in a VW bus exploring Mexico and places further afield.

Along the way, he co-founded Satloc, a crop-spraying company that pioneered the use of GPS in aerial chemical applications. He then moved to San Diego and founded Corsair Marine, a company that built trimaran sailboats. He also founded True North Venture Partners, a venture capital organization that used money to make even more money. By then he had accumulated some proper resources.

Despite his newfound wealth, John Walton apparently remained a really nice guy. He started a philanthropy called the Children’s Scholarship Fund that provided low-income kids with money to attend private schools. Like his dad, John still appreciated a modest lifestyle. While he and his wife Christy split their time between their trimaran sailboat and a historic beach house, he nonetheless drove an inexpensive and efficient Toyota hybrid car.

In 2003 his old Special Forces team held a reunion in Las Vegas in honor of the pilots who had supported them in Vietnam. By then CPT Thinh, the stone-cold South Vietnamese pilot who had saved his life in the A Shau Valley, had successfully relocated to Fargo, North Dakota.

He and Walton had remained close for thirty years after the war. However, Thinh lacked the resources to make it to the reunion. John Walton flew his jet up to Fargo, retrieved his old friend and his family, and took them to Vegas for the event.

By 2005 John Walton was worth $18.2 billion. He was the 4th-richest person in America and the 11th-richest person in the world. At 58 he had led a truly extraordinary life. He kept himself fit and healthy and enjoyed skiing, hiking, skydiving, flying, motorcycle riding, and scuba diving.

On June 27, 2005, at around 12:20 in the afternoon, John Walton lifted off from the Jackson Hole Airport in Wyoming in a CGS Hawk Arrow homebuilt ultralight airplane. Walton had performed a minor repair on the aircraft previously and improperly installed a rear locking collar on the elevator control torque tube. This allowed the torque tube to slide rearward after takeoff and produce slack in the elevator control cable. The cumulative result was a loss of pitch control. Walton was killed in the resulting crash.

Many folks die peacefully in their beds after a long life lived in obscure anonymity. Others may go out violently or at the mercy of some disease or other. John Walton lived life to the full. Warrior, medic, pilot, husband, father, and philanthropist—John Walton packed an awful lot of living into his 58 years.

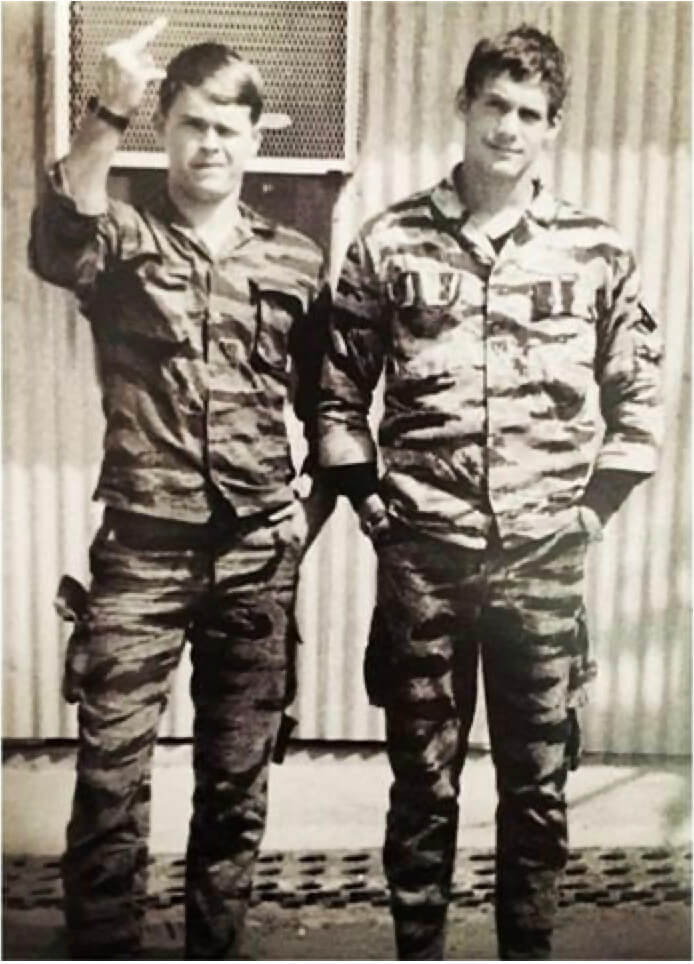

Addendum–I draw these projects from whatever I can find online. They are obviously only as accurate as the original source material. A teammate of John Walton’s named John Stryker Meyer reached out about some technical inaccuracies in this piece. Meyer is the character giving the finger to the photographer in one of the previous photos. After a delightful phone conversation I have made the changes. Based upon his personal descriptions, John Walton was clearly a truly extraordinary man.

Meyer authored a book on his experiences with MACV-SOG In Vietnam titled Across the Fence. It is available on Amazon. If the book is anything like he is it is likely a superb read. Thanks, brother.