Category: Soldiering

The Art of War: Jungle Warfare

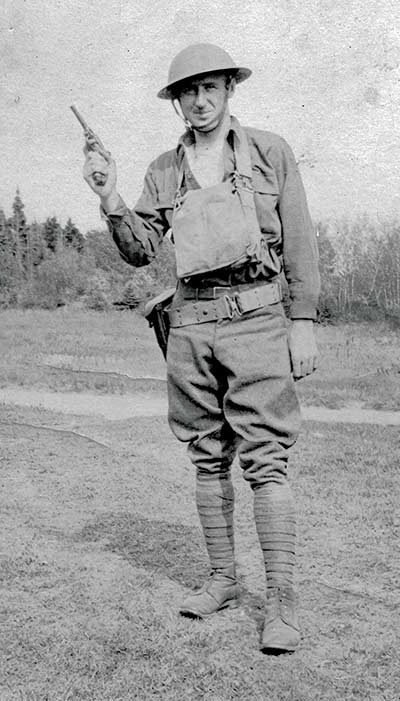

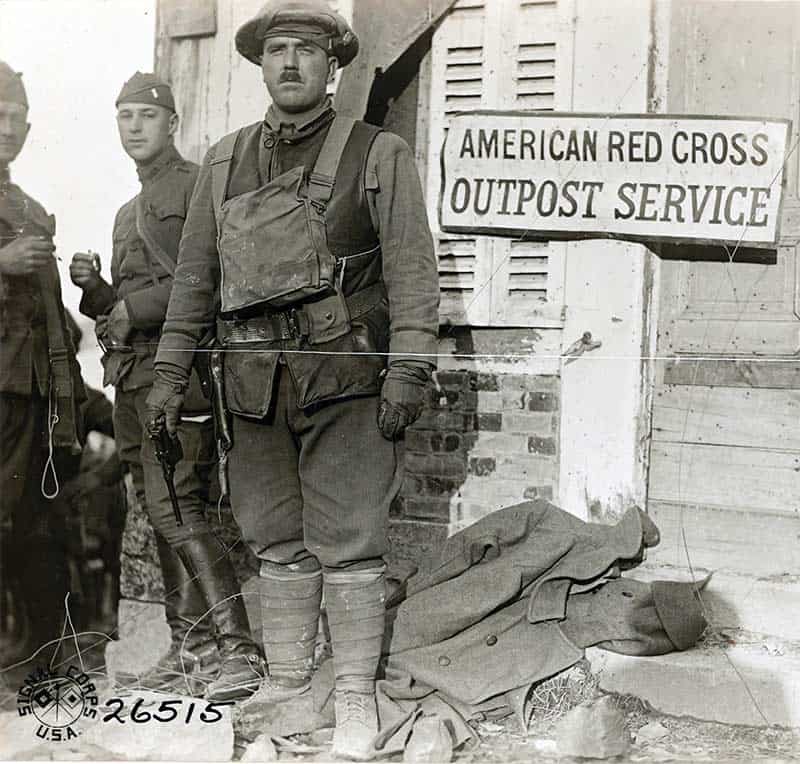

When American troops began to deploy to France in late 1917, they would soon realize the horrors of modern warfare. But they would also find one of the few pleasures for the combat soldier, and in WWI, that meant the beginning of a joyful harvest of German war trophy pistols.

WW I Trophy Hunting

By 1918, the German 9mm Pistole Parabellum, commonly known as the Luger pistol, became one of the most sought-after souvenirs of the Great War. The Luger and the Mauser C96 “Broom Handle” (chambered in 7.63x25mm) were not only prized trophies — the Doughboys found them quite useful and turned them against their former owners.

Even while there were plenty of U.S. .45 ACP pistols available (the M1911 auto pistol and the M1917 revolver), any red-blooded American boy will tell you two guns are better than one — particularly when your life depends on them. Even after the war was over, the American army of occupation in Germany continued its interest in war trophies, particularly the pistol variety.

The expression “The English fight for Honor, the French for Glory, but the Americans fight for Souvenirs!” is said to have originated in 1918. It is confirmed in multiple post-war assessments by German troops and civilians concerning American troops.

U.S. Intelligence officers conducted a series of interviews immediately after World War I. One letter from a German in Treves said: “The American discipline is excellent, but their thirst for souvenirs appears to be growing.” A shopkeeper from Bad Neuenahr quipped: “I alone have sold more Iron Crosses to American soldiers than the Kaiser ever awarded to his subjects.”

German pistols became scarce in the 1918–1919 era and unless you picked one up yourself (the hard way), their prices rose steeply. On the plus side, there were no gun laws in the U.S., so if a Doughboy could capture it, trade for it, or buy it, he could bring that pistol, rifle, or even machine gun home with him. After all, World War I was called “the war to end all wars” and nobody believed this world would be stupid enough to go to war again. But sadly, there would be another bigger and better chance for American troops to pick up German pistols on the battlefield just a quarter-century away.

Act II: ETO War Trophies

When U.S. forces met German troops in combat in World War II, American interest in German pistols, particularly the Luger, was reinvigorated. The U.S. Military Intelligence publication German Infantry Weapons (May 1943) described the Luger in detail for troops in the field:

“The Luger Pistol: Since 1908, the Luger pistol has been an official German military sidearm. In Germany, Georg Luger of the DWM Arms Company developed this weapon, known officially as Pistole 08, from the American Borchart pistol invented in 1893. The Luger is a well-balanced, accurate pistol. It imparts a high muzzle velocity to a small-caliber bullet but develops only a relatively small amount of stopping power.

Unlike the comparatively slow U.S. 45-caliber bullet, the Luger small-caliber bullet does not often lodge itself in the target and thereby impart its shocking power to that which it hits. With its high speed and small caliber, it tends to pierce, inflicting a small, clean wound. When the Luger is kept clean, it functions well. However, the mechanism is rather exposed to dust and dirt.

“Ammunition: Rimless, straight-case ammunition is used. German ammunition boxes will read ‘Pistolenpatronen 08’ (pistol cartridges 08). These should be distinguished from ‘Exerzierpatronen 08’ (drill cartridges 08). The bullets in these cartridges have coated steel jackets and lead cores. The edge of the primer of the ball cartridge is painted black. British- and U.S.-made 9mm Parabellum ammunition will function well in this pistol; the German ammunition will, of course, give the best results.”

Don’t Touch That …

The Luger’s popularity among U.S. troops did not go unnoticed by the Germans. Several wartime cautionary tales emerged as the Luger was sometimes used as “bait” for a booby-trap, ready to catch an over-eager trophy hunter. Other claims were circulated that German troops executed Americans captured carrying German pistols, but this was never substantiated. The February 1945 edition of the U.S. Intelligence Bulletin contained this warning:

“Charges Concealed in Weapons. The Germans sometimes conceal a small charge in the mechanism of a rifle or Luger pistol that they plan to leave behind in a fairly obvious place, to attract the attention of Allied soldiers. The charge, which is sufficiently powerful to injure a man severely, is detonated if the trigger of the weapon is pressed.”

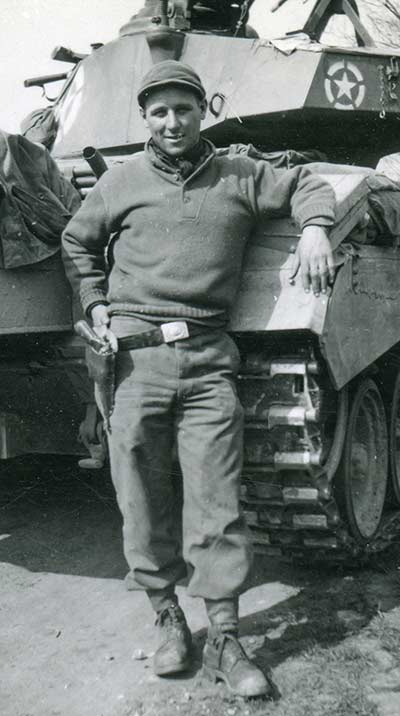

Bring-Backs & Send-Homes

Such was the mania among GI souvenir hunters to pick up German pistols (and any other German firearm) on the battlefield that the U.S. Army and the U.S. Customs Bureau went to great lengths to approve, then control, and then ultimately restrict American troops’ ability to bring or send the captured weapons home.

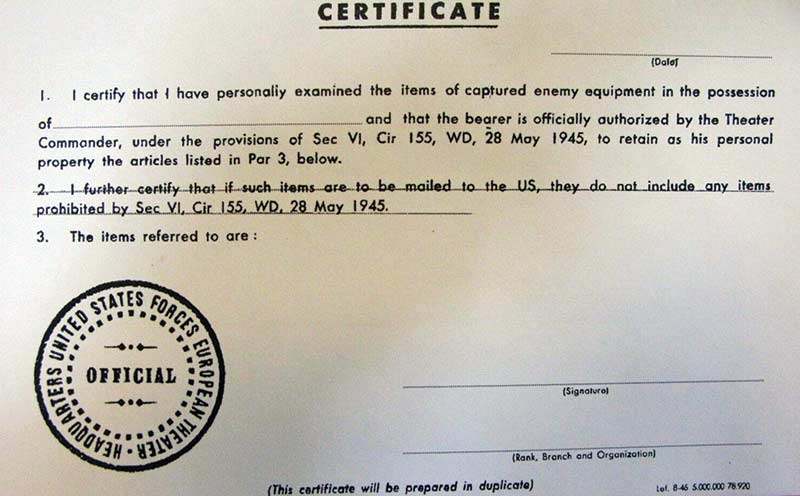

Beginning in 1944, a U.S. government certificate (often called “capture papers”) was provided to GIs that would allow them to send home or carry home a wide range of war trophies. Signed by their commanding officer, these rather vague certificates gave troops a near carte blanche to pass almost any captured firearm through U.S. customs, at least for a time.

Shortly after the war ended, a U.S. Army regulation effective May 28, 1945, limited War Trophy firearms to one per soldier and strictly enforced the prohibition of the importation of machine guns. It all looked good on paper anyway, but most GIs (and apparently their officers) ignored it. Your dad or grandpa put his captured pistol in his duffel bag and carried it home, or he packaged it up and mailed it to the states.

I’ve never seen any credible estimate on the number of German pistols brought home from the world wars. I’m not good at math, so I won’t guess at the total — other than to say, “a lot.” Even so, it is rare to find a WWII trophy pistol complete with its capture papers — the documentation doesn’t change much, but it is an interesting notch on a collector’s belt.

Technicalities

I did a little digging and found how Uncle Sam defined “war trophies” and the guidelines of how they could be possessed and brought to the United States as personal property.

“War Trophy: In order to improve the morale of the forces in the theatres of operations, the retention of war trophies by military personnel and merchant seamen and other civilians serving with the United States Army overseas is authorized under the conditions set forth in the following instructions. Retention by individuals of captured equipment as war trophies in accordance with the instructions contained herein is considered to be for the service of the United States and not in violation of the 79th Article of War.

“All effects and objects of personal use — except arms, horses, military equipment, and military papers — shall remain in the possession of prisoners of war, as well as metal helmets and gas masks.

“When military personnel returning to the United States bring in trophies not prohibited, each person must have a certificate in duplicate, signed by his superior officer, stating that the bearer is officially authorized by the theatre commander, under the provisions of this circular, to retain as his personal property the items listed on the certificate. The signed duplicate certificate will be retained by the Customs Bureau; the original will be retained by the bearer.

“Military personnel in theaters of operations may be permitted to mail like articles to the United States, except that mailing of firearms capable of being concealed on the person is prohibited. Parts of firearms mailed in circumvention of this prohibition are subject to confiscation by postal authorities. Parcels mailed overseas which contain captured materiel must also contain a certificate in duplicate, signed by the sender’s superior officer, that the sender is officially authorized by the theater commander to mail the articles listed on the certificate. The Customs Bureau will take up the signed duplicate certificate and leave the original inside the parcel.

“By order of the Secretary of War: G.C. Marshall Chief of Staff August 21, 1944.”

Since its inception in the early 1960s, the Boeing CH-47 Chinook helicopter has been a symbol of strength, adaptability and endurance in the world of aviation. With its unmistakable tandem rotor design and unparalleled lift capacity, the Chinook consistently demonstrated its ability to perform in a wide range of demanding situations, from military operations to disaster relief and beyond. In this article, Will Dabbs, MD delves into the fascinating history of the CH-47, examines its unique design features, and explores how this remarkable aircraft evolved over the decades to remain a critical asset in both military and civilian applications around the globe.

In my day, at least, when it was time to find out what sort of tactical aircraft you would fly, the U.S. Army didn’t make a terribly big deal about it. Though the rest of our military careers turned on the announcement, we all just gathered in a classroom toward the end of flight school at Fort Rucker, and our company commander read the results off of a computer printout. We were then left to be either elated or crushed as the situation dictated. I was personally crushed.

Not in so many words, but I told the Army I wanted to fly anything in the inventory except CH-47D Chinooks. I collected machine guns and had grown up reading everything I could find about World War II fighter planes. I chose the U.S. Army over the Air Force because I thought attack helicopters were more akin to P-38 Lightnings than might be F-15 fighters. I wanted to fly an airplane, not manage a bunch of systems. I had hoped that helicopter gunships might scratch that itch. And then I got Chinooks.

It’s weird, the U.S. Army. I actually did quite well in flight school, and my instructors all endorsed me for guns. The Chinook transition was quite the desirable slot, it was simply that I didn’t want it. There were other guys who got Snakes but wanted Chinooks. I always suspected Uncle Sam just hated us for some unfathomable reason.

Anyway, as a soldier, you are trained not to get what you want, so we just sucked it up and moved on. And then I actually strapped on a CH-47D, and I realized what all the fuss was about. The Chinook was a simply magnificent machine.

In helicopters, speed and maneuverability are a function of power, not aerodynamics. The Chinook has scads of that. My versions packed an aggregate 9,000 shaft horsepower into two Lycoming turboshaft engines. That made the big Chinook wicked fast.

VNE (Velocity never to exceed) for a CH-47D was 170 knots, or about 195 miles per hour. The Blackhawk and Apache were faster, but only in a dive. The Chinook would walk away from them both in level flight. I actually did that myself several times just to prove a point. When deftly wielded, the CH-47D would turn on a dime as well.

Most conventional helicopters are slaves to tailwinds. The tail rotor on a traditional helicopter is just there to counteract main rotor torque and keep the machine pointed in the right direction. Whatever power is required to keep that thing spinning is essentially wasted. By contrast, the massive twin counter-rotating rotors on the Chinook funnel all that power into lift. It also doesn’t much care what direction it is pointed. I once held a Chinook at a stationary hover in a mountain pass in Alaska and read 73 knots on the airspeed indicator.

Semi-rigid rotor systems like those of the Cobra or Huey cannot be operated at less than one-half of one positive G. Unloading the rotors, like hugging terrain at speed while flying NOE (nap of the earth) across a hilltop, can cause them to come apart. By contrast, the fully-articulated system on the Chinook feasted on negative G’s. According to the simulator, a CH-47D will execute a splendid aileron roll, though I have never tried that myself in the real world.

Details

The D-model CH-47 tops out at 50,000 pounds and is 98 feet long from rotor tip to rotor tip. It features seatbelts for 33 combat troops, but can carry lots more in a pinch. The fuselage is 52 feet long, and each rotor blade spans 30 feet. While weight and balance are always important in helicopters, I found that the Chinook would carry most anything you could stuff into it.

The service ceiling for the CH-47D is listed as 20,000 feet, but I have personally taken one to just shy of 22k. The aircraft has mounts for three defensive machine guns. Ours were sucktastic D-model M60 machine guns. Nowadays, they use M240 guns. The Night Stalkers of the 160th SOAR (Special Operations Aviation Regiment) operate Dillon M134D miniguns. Those are undeniably sexy cool, but an electrically-powered machine gun is just ballast if the electrical system fails or is shot away.

Unlike lesser U.S. Army helicopters, the Chinook is a fantastic instrument platform. The AFCS (Advanced Flight Control System) will fly the aircraft hands-off in cruise mode. Heading changes can be easily effected simply by turning a knob on the instrument panel that orients a heading bug on the HSI (Horizontal Situation Indicator). I’m sure all that is digital today. All of the flight instruments are perfectly replicated on both sides of the cockpit, so the machine is equally friendly from either seat.

CH-47F Chinook Technical Specifications

Here are the published Chinook specifications:

| Crew | 3 (2 pilots, 1 flight engineer) |

| Load Carrying Capacity | 33 troops or 24 litters |

| Length, Overall | 98′ |

| Length, Fuselage | 52′ |

| Weight, Empty | 24,578 lbs |

| Weight, Maximum Takeoff | 50,000 lbs |

| Powerplant | 2x Lycoming T55-GA-714A turboshaft engines with 4,733 SHP each |

| Velocity, never to exceed | 170 knots |

| Service Ceiling | 20,000′ |

| Armament | 3x M240 machine guns |

Pilot Stuff

The tandem rotor design of the CH-47D offers certain benefits not afforded by lesser aircraft. With a little practice, a skilled pilot could cause the machine to pivot precisely around the forward rotor head, the aft head, or the cargo hook in the middle. An awe-inspiring spiraling vertical liftoff executed at maximum power settings was called a Black Cat takeoff. No other machine could really do that.

Pinnacle landings were uniquely cool. With the flight engineer providing guidance the aft landing gear could be precisely located on a mountaintop or something similar. Then by setting the cyclic to the rear, the pilot could plant the aft gear and then use the thrust (what would be the collective in a lesser aircraft) to adjust pitch and maintain station. The same technique could be used to taxi the big helicopter on its back two wheels. The Chinook also made a great paradrop platform. You could feel a little bump through your seat every time one of the heavily-laden paratroopers left the aft ramp.

Practicalities of the Chinook

U.S. Army doctrine, at least in my day before there were so many blasted drones, was to push the tactical aircraft as close to the front as possible. That meant we lived out of our machines. We actually affectionately referred to the CH-47D as the Boeing Hilton. With so much space, there was plenty of room for the crew to lower the sling seats and use them as cots. I have spent weeks on end living out of my aircraft. After an extended period in the field, the inside of the aircraft begins to look like a homeless encampment, but it is still better than the alternative.

Operations in the Arctic bring their own unique challenges. As the machine is basically a big aluminum tube, it doesn’t take long for the aircraft to become cold-soaked at fifty below zero. Our arctic sleeping bags were up to the task, but it was always a gut check to see who was going to be the first out of their fart sack to go crank the auxiliary power unit and get that 200,000-BTU heater cooking. That puppy ran off of jet fuel and would render the Boeing Hilton mosty toasty in no time, no matter how ghastly it was outside.

I later got to fly both AH-1S Cobras and OH-58A/C helicopters. I learned to fly on Vietnam-era UH-1H Hueys in flight school. The Huey had the nostalgia, and the Snake the sex appeal. Driving Aeroscouts single-pilot with the doors off was like flying a motorcycle. However, nothing can compare to the sensation of power you get when you tug the up stick in a CH-47D and feel those 9,000 horses kick you in the butt. That was a wild ride, indeed.

Everybody dies. That’s an easy thing to digest in the abstract. When you’re young, fit, and healthy it is often even comical. However, when the situation grows dire all that comedy is excised. Having seen my share I have been surprised at how many folks, even really old people, find the event so unexpected. Death is a big deal, and it warrants a little forethought.

The average life expectancy in America is 78.57 years. We all presume we will drift off quietly in our sleep and be too old to care. However, death comes for many in much darker more sordid ways.

There is little more viscerally horrifying than the prospect of being eaten alive. Getting gobbled up by some massive predator would actually likely be faster and less agonizing than a lot of the other alternatives. However, on a primal level, most folks just don’t want to end up as food. For several hundred Japanese grunts pulling garrison duty on an obscure island in the South Pacific in 1945, however, their gory demise was indeed extra horrible.

The Setting

The Imperial Japanese Army captured Ramree Island, a 520-square mile landmass off the coast of Rakhine State in what is today known as Myanmar, in 1942. The island is separated from the mainland by a narrow strait that averages a mere 150 meters across. For three years this Japanese garrison saw little to no action. In January of 1945, however, they would earn their combat pay.

In 1945 the garrison consisted of around 1,000 men assigned to the Japanese 54th Division and commanded by one Kanichi Nagazawa. On 21 January a flotilla containing the battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth, the escort carrier HMS Ameer, the light cruiser HMS Phoebe, and three British destroyers opened up on Japanese artillery positions established in caves overlooking the proposed landing beaches. This armada was supported by American B24 Liberators, B25 Mitchells, and P47 Thunderbolt fighter bombers.

By this point in the war, the Japanese were most typically staging their primary defenses inland in-depth, so the assault force landed essentially unopposed. The real chaos would come later. Two small craft struck mines, but the invasion itself was otherwise uneventful. As the Indian troops under Brigadier RD Cotterell-Hill advanced, however, the Japanese defenders put up a spirited fight.

A joint force comprised of Indian Infantry along with Royal Marines outflanked the Japanese positions, rendering them untenable. In response, the Japanese defenders fell back intending to join a second, larger element on the opposite side of the island. To do so, however, these battle-weary Japanese troops had to traverse 16 kilometers’ worth of fetid mangrove swamp.

Like a Bad Movie

By the time the Japanese defenders struck out into the swamp, the British had the entire area surrounded. Realizing the plight of the defenders to be hopeless, the British addressed the retreating men via loudspeakers entreating them to surrender. Alas, the Japanese during WW2 didn’t do a great deal of surrendering. The stage was set for Something Truly Horrible. A British soldier named Bruce Wright who later became a naturalist of some renown described the proceedings thusly—

“That night [of 19 February 1945] was the most horrible that any member of the M. L. [motor launch] crews ever experienced. The scattered rifle shots in the pitch black swamp punctured by the screams of wounded men crushed in the jaws of huge reptiles, and the blurred worrying sound of spinning crocodiles made a cacophony of hell that has rarely been duplicated on earth. At dawn the vultures arrived to clean up what the crocodiles had left….Of about one thousand Japanese soldiers that entered the swamps of Ramree, only about twenty were found alive.”

The Weapons

The Japanese fought World War 2 with what were arguably the best and worse Infantry weapons in the world. The Type 26 revolver and Type 94 pistol were inexplicably wretched. Though the Type 26 was meticulously well crafted, there was no positive cylinder stop to keep the cylinder properly indexed. Bumping the gun could rotate the cylinder such that the next shot might fall over an empty chamber.

The Type 94 is universally extolled as the worst combat handgun in military history. The grip tapers down so it feels like it is going to squirt out of your hand when you grasp it tightly. The magazine floorplate is not positively retained, so it can slip off and spill the contents of the magazine out of the butt. Most importantly, the transfer bar is exposed on the side of the gun. This means a good squeeze on the side will fire the weapon without the trigger having been touched. The same result can be elicited by setting the gun down vigorously on an uneven surface. Wow.

Japanese machineguns were heavy, reliable, and beautifully crafted. However, they used three different cartridges, two of which looked pretty much the same on the outside. The logistics of trying to keep all those guns fed across the vast Pacific theater would be unimaginably daunting. The Type 99 rifle, however, was a superb example of the military art.

In 1939 the Japanese designed a new bolt-action service rifle to replace the previous Type 38. They found that the 7.7x58mm Arisaka cartridge used in their machineguns was vastly superior to the 6.5x50mm round fired by the Type 38. The Imperial Japanese Army simply adapted the proven Type 38 design to fire the new round. Ultimately some 3.5 million copies were produced at nine different arsenals.

The Type 99 was produced in four distinct variants. The most common was the Type 99 Short Rifle. A limited production Type 99 Long Rifle was fielded as well. Additionally, there was a Type 99 Sniper variant equipped with a fixed-power optic. One version incorporated an offset optic mount and straight bolt handle that would accommodate stripper clips loaded from above. A second variant had a bent bolt and a centerline scope mount that necessitated rounds be loaded one at a time. There was a takedown paratrooper version of the basic rifle as well.

The Type 99 was the first mass-produced Infantry arm to include a chrome-lined bore for use in fetid jungle climes. Early versions of the Type 99 were meticulously executed with a variety of curious ditzels of dubious tactical utility. The first marks featured a pressed steel action cover, a flimsy folding wire monopod, and a bizarre antiaircraft sight with fold-out wings. This contrivance was intended to help Infantrymen on the ground determine proper lead for enemy aircraft crossing laterally. All of this stuff was deleted from production by the end of the war.

The safety on the Type 99 was a meticulously knurled knob located on the rear aspect of the bolt. To manipulate this device, one would press inward with the palm and rotate the knob 1/8 turn. This design seems clumsy when compared to the simple safety lever of the British Lee-Enfield or German Mauser designs.

As the war progressed and the full force of the massed B29 raids took their toll on Japanese industry the quality of the Type 99 rifle dropped off precipitously. These late-war versions were known as “last ditch” rifles. Such crude examples typically had no finish on the steel, rough tooling marks, and a simple fixed aperture rear sight. The oversized safety knob was left rough and unfinished, while the crude wooden buttplate was held in place via nails rather than screws. Many of these late-war rifles used a length of hemp rope in lieu of a sling as well.

Each Type 99 rifle included a chrysanthemum engraved on the receiver ring signifying personal ownership by the Emperor. Many to most examples sold today have had the mum ground off as a sign of respect for the defeated monarch. I have read that General MacArthur himself mandated this practice in an effort at smoothing out the occupation. Examples with intact mums command markedly higher prices as a result. Tests conducted by the NRA after the war comparing bolt-action rifles showed the Japanese Type 99 to be the strongest action used by any combatant nation during the conflict.

Aftermath

The numbers are disputed, but the generalities are reliable. The battle went on for six weeks. Of roughly 1,000 Japanese troops who retreated into the swamp, some 500 made it across the waterway to the mainland. Another 20 were captured. The rest were consumed by the island. Some likely succumbed to sharks while crossing to the continent, while others undoubtedly fell to British fire and disease. A not insubstantial number, however, were indeed eaten by crocodiles.

Around 1,000 people each year are estimated to succumb to crocodilians of all species today. The saltwater crocs endemic to Ramree Island in 1945 would have reached twenty feet or more and weighed some 2,000 pounds.

The Guinness Book lists the carnage in Ramree Island’s mangrove swamps as the worst example of crocodile predation on humans in history. There were 500 or so troops who remained unaccounted for that night. Theirs was an undeniably ghastly end.

Special thanks to World War Supply for the cool replica gear used in our photographs.