WASHINGTON – Navy Capt. Brad Geary was on the path to becoming an admiral on Feb. 4, 2022, when he got “earth-shattering” news: one of his Navy SEAL candidates was found unresponsive hours after completing the training program’s “Hell Week.”

Seaman Kyle Mullen, 24, had just pushed himself through the most physically intense period in the SEALs’ famously arduous boot camp when fellow candidates discovered him in his room, blue in the face.

Medics would later pronounce him dead at a hospital.

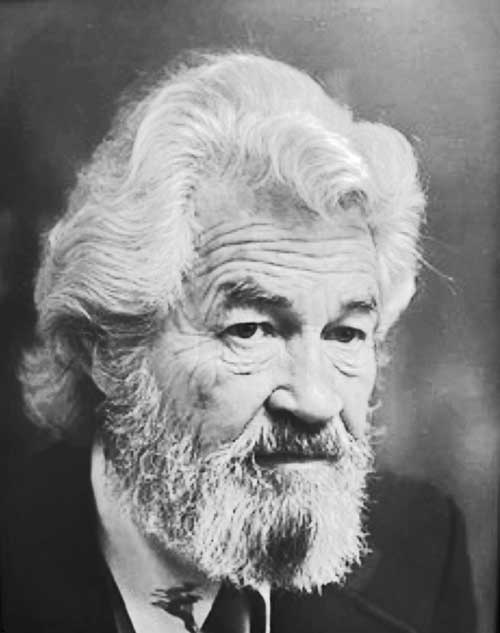

“I’ll never be able to take that weight off my shoulders,” Geary said in an exclusive interview with The Post this week. “I’ve lost many teammates in my career, unfortunately. Too many. But this was the first one under my command.”

Three months before Mullen’s death, Geary had traveled to Washington, DC to accept the Navy’s top honor for “inspirational leadership,” the Vice Adm. James Bond Stockdale Award.

Now, in the wake of a highly critical Navy investigation into Mullen’s death, the SEAL officer faces scrutiny from the Navy, Congress and the press, and plans to retire from the service without adding a star to his uniform.

“You’re grieving the death of a dream every day,” said Geary, who is speaking out for the first time since Mullen’s tragic death. “I know by coming forward with the press on this one, I’m committing a cultural faux pas that will put me out of graces with my community, but I have to … I am laying down my career for my cadre of candidates to be their voice and defend them because no one else is.”

Tough enough

An autopsy report revealed Mullen died of a combination of pneumonia and swimming-induced pulmonary edema – a condition common in SEAL candidates, who experience fluid buildup in the lungs after prolonged exposure to frigid waters.

But Mullen had powered through in the middle of winter, enduring a five-and-a-half day stretch in which SEAL candidates are allowed just four hours of sleep each night, run a total of more than 200 miles, swim in the frigid ocean and complete other physical training for more than 20 hours per day.

Navy investigators swarmed Geary’s command following Mullen’s death.

The captain says he laid his concerns about a rising number of SEAL candidates dropping out of the training program he took over in 2020 and his efforts to conduct a study to identify the cause.

Consulting with experts and academics, Geary found a multitude of reasons for rising dropout rates – including the coronavirus pandemic and “generational shifts” – but he said his concerns were ignored when brought to Navy leadership.

“Nobody really wanted to hear our message until after Kyle Mullen died,” he told The Post. “We beat that drum incessantly and it really did not resonate.”

Geary also made a number of changes to the program to prevent attrition, such as mandating six hours of sleep before Hell Week and eliminating heavy rucksacks from runs in early training phases.

But when the report came out, Geary found himself depicted as a barbarian, out-of-touch leader whose cadre of trainers pushed SEAL candidates too hard.

“Capt. Geary maintained a view that the high attrition was caused, among other reasons, by the current generation having less mental resilience, or being less tough,” said the report, which was unsealed last week.

The career SEAL officer vehemently denied the allegation to The Post, stating on multiple occasions that he would never say such a thing and that such an opinion would be the antithesis of his personal leadership philosophy.

“One of the things that was misstated in that report was this notion that I somehow blamed the next generation for being mentally weak, which is what resulted in the attrition,” Geary said. “Those were not my words. I never said that. Those closest to me in my command would say I never said that.”

“That’s flippant and irresponsible and just not true.”

To the contrary, Geary said he knew the next generation of SEALs were tough, giving multiple anecdotes throughout his two-hour interview with The Post and criticizing those who say young people are weak.

“It’s very easy to say, ‘Well, damn the next generation’ and make fun of them … [but] I’ve reinforced this throughout my entire time as as commanding officer: It’s on us as leaders to adjust to the next generation,” Geary said. “It’s not enough to say ‘You have to be like us and we expect you to perform like we did.’

“No, no, we need to look for their strengths and look for their weaknesses. Be objectively critical of those and then help them develop what we need them to have for the SEAL teams and the missions that will ask them to do,” he added.

Ironically, it was Mullen’s fierce, never-quit mentality that contributed to his death.

He’d turned down offers of medical treatment as he coughed up blood and fluids that week, and even called himself “such a p—y” because he was struggling to breathe the day he died, the report said.

“[Mullen], intent on doing everything possible to complete the pipeline, was at increased risk of serious injury during Hell Week conditions of extreme fatigue and environmental exposure, with decreased ability to compensate and recover from such injuries,” the report said.

Fall from grace

But the investigation placed the heaviest blame on Geary and his staff, alleging the latter abused the Special Forces hopefuls while the captain looked the other way.

It also claimed that his leadership fostered an environment where seeking medical attention was discouraged, young SEAL trainers grew extreme in their practices and the voices of retired SEALs brought in as advisers were silenced.

Geary denied the allegations, saying he was “disappointed” with the results of the investigation, defending his team against accusations of wrongdoing.

“Our cadre deserved to be trusted and the American people deserve to know that they can trust the SEAL community, and it’s frustrating to me that [the report] unjustly undermines that trust,” he said.

His attorney, Jason Wareham, criticized the Navy investigation, alleging it was mishandled from the start and “perpetuates the Navy’s narrative to wrongfully discredit my client through twisted quotes, misconstructions and mishandling of evidence that has existed since the start.”

For example, the Army coroner failed to test Mullen for certain performance-enhancing drugs despite knowing some were discovered in his belongings after he died.

While Mullen tested negative for steroids, other PEDs, including human growth hormone and testosterone, were found with syringes in his car, according to the report.

Geary received an official letter of reprimand after the Navy investigation, but was allowed to continue his service in the military.

However, the letter is likely a career-killer, as his name has been sullied throughout the course of the investigation.

“I genuinely love everyone that is entrusted to my care as a leader, and as the commanding officer of [the SEAL training program,] I loved my candidates,” Geary told The Post. “I loved Kyle Mullen; I grieved his loss and still do. I will carry that weight with me forever.”

A mother’s pain

But Geary’s fate is just fine with the late sailor’s mother, Regina Mullen.

If anything, she told The Post she’d like to see Geary, who still serves in the Navy but no longer leads the training program, fired for what she claimed was his role in her son’s death.

“I said, ‘You are a murderer. You murdered him,’” she said of her conversation with Geary in the wake of her son’s death, she told The Post. “I think he feels bad, but everybody feels bad when you’re caught.”

Regina Mullen went on to suggest that no one should go through the elite special forces training course.

A registered nurse, she said her son would not have died if he had been given proper medical care when showing signs of respiratory distress.

“If you’re sick, you’re weak – that’s what they were like promoting and cultivating,” she said. “I don’t even know that you need the SEALs [in the military.]”

From the beginning, Regina wanted accountability for the command and worried the Navy would float the drugs found in Kyle’s car as the cause of his death.

She said this week that she told the service to write that there was no evidence that PEDs caused her son’s death in a press release, a request that was honored.

At the very least, Regina Mullen said, the command’s medics who conducted the mandatory post-Hell Week medical check on her son should have caught his debilitating condition and been ordered to monitor him.

“They should have never let that medical team go home,” she told The Post. “They saw my son swallowing, spitting up blood – it was visible by the eye … That’s disgusting. It was abuse of power.”

After her son’s death, Regina Mullen worked with Rep. Chris Smith (R-NJ), who wrote legislation aimed at improving medical care and oversight of high-stress military training programs.

“When I first met Regina, she made it clear that no other parent should ever have to endure her pain,” Smith said in a statement last week after he and Regina met with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.). “She has made incredible strides in her goal to ensure these young men are as healthy as possible and have access to a world-class medical monitoring capability.”

Independent investigation

The bereaved mother is now pushing Congress to direct the Pentagon’s internal watchdog to investigate the case after advocating for the command investigation that alleged Geary and his team were at fault in Kyle’s death.

She’s also spoken to media outlets calling for accountability for the officers.

“The safety of the men, that’s their primary responsibility,” she told The Post on Friday.

Geary’s attorney said he is confident that further investigation would clear his client of the scrutiny that has surrounded him since the initial report was completed last fall.

“If the Navy regrettably acts against my client, administratively or punitively, the resulting process will undoubtedly bring the needed antiseptic of sunshine to this issue,” Wareham said.

Former Acting Defense Secretary Christopher Miller told The Post those most deserving of accountability are likely Geary’s superiors, claiming the Pentagon’s bureaucracy regularly pushes blame and punishment onto those in charge of individual commands after tragedies.

“The services are extremely reluctant to ever investigate themselves, and when they have to because they realize there’s pressure, the initial investigation is always flawed [with] cursory bias,” he said Friday. “And in this one, clearly, the mother was not accepting the results of it.”

Kash Patel, Miller’s former chief of staff and longtime friend of Geary’s, agreed, saying he believes the Navy is cracking down on the captain to avoid taking responsibility for ignoring Geary’s early warnings about attrition.

“It was a tragic death, there needs to be a justification for it and someone needs to be punished,” Patel said. “And rather than punish the people who are actually responsible for it – the secretary of the Navy and the admirals – they reach down and create a scapegoat and unfortunately … we have a tragic way of attacking our actual heroes.”

The hope is that the new IG investigation will bring more clarity about what actually happened, make sense of conflicting narratives and offer suggestions about how it can be prevented in the future.

“I am extremely skeptical of any investigation conducted by the United States military,” Miller said. “That’s why you have Inspector Generals [who] are typically more unbiased based on their charter and more forthright and more revealing.

“But here’s the thing,” he added, “until Congress gets involved and forces an independent investigation, that’s the only way you get any anything meaningful out of the military.”

The post Navy SEAL training commander speaks out after scathing report on ‘shattering’ candidate death appeared first on New York Post.