One Really Bad Dude

One Really Bad Dude

Back in the Days of Real Gangsters of America. Mr. D was the King of the Publicity for these folks.

Here is his story:

John Herbert Dillinger (/dɪlɪndʒər/; June 22, 1903 – July 22, 1934) was an American gangster in the Depression-era United States. He operated with a group of men known as the Dillinger Gang or Terror Gang, which was accused of robbing 24 banks and four police stations, among other activities. Dillinger escaped from jail twice. He was also charged with, but never convicted of, the murder of an East Chicago, Indiana, police officer who shot Dillinger in his bullet-proof vest during a shootout, prompting him to return fire; despite his infamy, it was Dillinger’s only homicide charge.

He courted publicity and the media of his time ran exaggerated accounts of his bravado and colorful personality, styling him as a Robin Hood figure.[1] In response, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover developed a more sophisticated Bureau as a weapon against organized crime, using Dillinger and his gang as his campaign platform.[1]

After evading police in four states for almost a year, Dillinger was wounded and returned to his father’s home to recover. He returned to Chicago in July 1934 and met his end at the hands of police and federal agents who were informed of his whereabouts by Ana Cumpănaş (the owner of the brothel where Dillinger had sought refuge at the time). On July 22, 1934, the police and the Division of Investigation[2] closed in on the Biograph Theater. Federal agents, led by Melvin Purvis and Samuel P. Cowley, moved to arrest Dillinger as he exited the theater. He drew a Colt Model 1908 Vest Pocketand attempted to flee, but was killed. This was ruled as a justifiable homicide.[3][4]

Early life

Family and background[edit]

John Dillinger was born on June 22, 1903, in Indianapolis, Indiana,[5] the younger of two children born to John Wilson Dillinger (1864 –1943) and Mary Ellen “Mollie” Lancaster (1860–1907).[6]:10

According to some biographers, his German grandfather, Matthias Dillinger, emigrated to the United States in 1851 from Metz, in the region of Lorraine, then under French sovereignty.[7] Matthias Dillinger was born in Gisingen, near Dillingen in present-day Saarland. John Dillinger’s parents had married on August 23, 1887. Dillinger’s father was a grocer by trade and, reportedly, a harsh man.[6]:9 In an interview with reporters, Dillinger said that he was firm in his discipline and believed in the adage “spare the rod and spoil the child”.[6]:12

Dillinger’s older sister, Audrey, was born March 6, 1889. Their mother died in 1907 just before his fourth birthday.[6][8]Audrey married Emmett “Fred” Hancock that year and they had seven children together. She cared for her brother John for several years until their father remarried in 1912 to Elizabeth “Lizzie” Patel (1878–1933). They had three children, Hubert, born 1912, Doris M. (1918–2001) and Frances Dillinger (1922–2015).[8][9]

Reportedly, Dillinger initially disliked his stepmother, but he eventually came to fall in love with her. The two eventually began a relationship that lasted 3 years.[10]

Formative years and marriage[edit]

As a teenager, Dillinger was frequently in trouble with the law for fighting and petty theft; he was also noted for his “bewildering personality” and bullying of smaller children.[6]:14 He quit school to work in an Indianapolis machine shop. His father feared that the city was corrupting his son, prompting him to move the family to Mooresville, Indiana, in 1921.[6]:15Dillinger’s wild and rebellious behavior was unchanged, despite his new rural life. In 1922, he was arrested for auto theft, and his relationship with his father deteriorated.[6]:16–17

His troubles led him to enlist in the United States Navy, where he was a Fireman 3rd Class assigned aboard the battleship USS Utah,[11] but he deserted a few months later when his ship was docked in Boston. He was eventually dishonorably discharged.[6]:18–20

Dillinger then returned to Mooresville where he met Beryl Ethel Hovious.[12] The two were married on April 12, 1924. He attempted to settle down, but he had difficulty holding a job and preserving his marriage.[1]

Dillinger was unable to find a job and began planning a robbery with his friend Ed Singleton.[6]:22 The two robbed a local grocery store, stealing $50.[6]:26 While leaving the scene, the criminals were spotted by a minister who recognized the men and reported them to the police. The two men were arrested the next day. Singleton pleaded not guilty, but after Dillinger’s father (the local Mooresville Church deacon) discussed the matter with Morgan County prosecutor Omar O’Harrow, his father convinced Dillinger to confess to the crime and plead guilty without retaining a defense attorney.[6]:24Dillinger was convicted of assault and battery with intent to rob, and conspiracy to commit a felony. He expected a lenient probation sentence as a result of his father’s discussion with O’Harrow, but instead was sentenced to 10 to 20 years in prison for his crimes.[8] His father told reporters he regretted his advice and was appalled by the sentence. He pleaded with the judge to shorten the sentence, but with no success.[6]:25 (During the robbery, Dillinger had struck a victim on the head with a machine bolt wrapped in a cloth and had also carried a gun which, although it discharged, hit no one). En route to Mooresville to testify against Singleton, Dillinger briefly escaped his captors, but was apprehended within a few minutes.[6]:27 Singleton had a change of venue and was sentenced to a jail term of 2 to 14 years. He was killed on August 31, 1937, by a train when he passed out, drunk, on a railroad track.[13]

Prison time[edit]

Within Indiana Reformatory and Indiana State Prison, from 1924 to 1933, Dillinger began to become embroiled in a criminal lifestyle. Upon being admitted to the prison, he is quoted as saying, “I will be the meanest bastard you ever saw when I get out of here.”[6]:26 His physical examination upon being admitted to the prison showed that he had gonorrhea. The treatment for his condition was extremely painful.[6]:22 He became embittered against society because of his long prison sentence and befriended other criminals, such as seasoned bank robbers like Harry “Pete” Pierpont, Charles Makley, Russell Clark, and Homer Van Meter, who taught Dillinger how to be a successful criminal. The men planned heists that they would commit soon after they were released.[6]:32 Dillinger studied Herman Lamm‘s meticulous bank-robbing system and used it extensively throughout his criminal career.[citation needed]

His father launched a campaign to have him released and was able to get 188 signatures on a petition. Dillinger was paroled on May 10, 1933, after serving nine and a half years. Dillinger’s stepmother became sick just before he was released from the prison, and died before he arrived at her home.[6]:37 Released at the height of the Great Depression, Dillinger had little prospect of finding employment.[6]:35 He immediately returned to crime.[6]:39

On June 21, 1933, he robbed his first bank, taking $10,000 from the New Carlisle National Bank, which occupied the building at the southeast corner of Main Street and Jefferson (State Routes 235 and 571) in New Carlisle, Ohio.[14] On August 14, Dillinger robbed a bank in Bluffton, Ohio. Tracked by police from Dayton, Ohio, he was captured and later transferred to the Allen County Jail in Lima to be indicted in connection to the Bluffton robbery. After searching him before letting him into the prison, the police discovered a document which appeared to be a prison escape plan. They demanded Dillinger tell them what the document meant, but he refused.[8]

Dillinger had helped conceive a plan for the escape of Pierpont, Clark and six others he had met while in prison, most of whom worked in the prison laundry. Dillinger had friends smuggle guns into their cells, with which they escaped, four days after Dillinger’s capture. The group, known as “the First Dillinger Gang,” comprised Pete Pierpont, Russell Clark, Charles Makley, Ed Shouse, Harry Copeland, and John “Red” Hamilton, a member of the Herman Lamm Gang. Pierpont, Clark, and Makley arrived in Lima on October 12, where they impersonated Indiana State Police officers, claiming they had come to extradite Dillinger to Indiana. When the sheriff, Jess Sarber, asked for their credentials, Pierpont shot Sarber dead, then released Dillinger from his cell. The four men escaped back to Indiana, where they joined the rest of the gang.[8]

Bank robberies[edit]

Dillinger is known to have participated with The Dillinger Gang in twelve separate bank robberies, between June 21, 1933 and June 30, 1934.[citation needed]

Relationship with Evelyn Frechette[edit]

Evelyn “Billie” Frechette met John Dillinger in October 1933, and they began a relationship on November 20. After Dillinger’s death, Billie was offered money for her story and eventually penned a memoir for the Chicago Herald and Examiner in August 1934.[15]

Escape from Crown Point, Indiana[edit]

Dillinger was finally caught by Matthew “Matt” Leach, the chief of the Indiana State Police, and imprisoned within the Crown Point jail sometime after committing a robbery at a bank located in East Chicago on January 15, 1934. The local police boasted to area newspapers that the jail was escape-proof and posted extra guards to make sure. What happened on the day of Dillinger’s escape on March 3 is still open to debate. Deputy Ernest Blunk claimed that Dillinger had escaped using a real pistol, but FBI files make clear that Dillinger carved a fake pistol from a potato. Sam Cahoon, a trustee that Dillinger first took hostage in the jail, believed that Dillinger had carved the gun with a razor and some shelving in his cell. However, according to an unpublished interview with Dillinger’s attorney, Louis Piquett and his investigator, Art O’Leary, O’Leary claimed to have sneaked the gun in himself.[16]

On March 16, Herbert Youngblood, a fellow escapee from Crown Point, was shot dead by three police officers in Port Huron, Michigan. Deputy Sheriff Charles Cavanaugh was fatally wounded in the battle and died a few hours later. Before he died, Youngblood told the officers that Dillinger was in the neighborhood of Port Huron, and immediately officers began a search for the escaped man, but no trace of him was found. An Indiana newspaper reported that Youngblood later retracted the story and said he did not know where Dillinger was at that time, as he had parted with him soon after their escape.[17]

Dillinger was indicted by a local grand jury, and the Bureau of Investigation (a precursor of the Federal Bureau of Investigation)[2] organized a nationwide manhunt for him.[18] After escaping from Crown Point, Dillinger reunited with his girlfriend, Evelyn Frechette, just hours after his escape at her half-sister Patsy’s Chicago apartment, where she was also staying (3512 North Halsted).

According to Billie’s trial testimony, Dillinger stayed with her there for “almost two weeks,” but the two actually had traveled to the Twin Cities and moved into the Santa Monica Apartments, Unit 106, 3252 South Girard Avenue, Minneapolis, on March 4 (moving out on March 19)[19][20] and met up with Hamilton (who had been recovering for the past month from his gunshot wounds in the East Chicago robbery), and mustered a new gang, and the two joined Baby Face Nelson‘s gang, composed of Homer Van Meter, Tommy Carroll and Eddie Green.[clarification needed]

Three days after Dillinger’s escape from Crown Point, the second Dillinger Gang robbed a bank in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. A week later they robbed First National Bank in Mason City, Iowa.[citation needed]

Lincoln Court shootout[edit]

|

|

This section may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (June 2015)

|

Dillinger and Billie eventually moved into apartment 303 of the Lincoln Court Apartments, 93-95 South Lexington Avenue (now Lexington Parkway South) in St. Paul, Minnesota, on Tuesday, March 20, using the aliases “Mr. & Mrs. Carl T. Hellman”. The three-story apartment complex (still in operation)[21] had 32 apartments — 10 units on each floor, plus two basement units.[22][23]

Daisy Coffey, the landlord/owner, would testify at Frechette’s trial that she spent most evenings during the Hellmans’ stay furnishing apartment 310, which enabled her to observe what was happening in apartment 303 directly across the courtyard. On March 30, Coffey went to the FBI’s St. Paul field office to file a report, including information about the couple’s new Hudson sedan parked in the garage behind the apartments. The building was placed under surveillance by two agents, Rufus Coulter and Rusty Nalls, that night, but they saw nothing unusual, mainly due to the blinds being drawn.[24]

The next morning at approximately 10:15, Nalls circled around the block looking for the Hudson, but observed nothing. He parked, first on Lincoln (the north side of the apartments), then on the west side of Lexington, at the northwest corner of Lexington and Lincoln, and remained in his car while watching Coulter and St. Paul Police detective Henry Cummings, pull up, park, and enter the building.[25] Ten minutes later, by Nalls’s estimate, Van Meter parked a green Ford coupe on the north side of the apartment building.[26]

Meanwhile, Coulter and Cummings knocked on the door of apartment 303. Frechette answered, opening the door two to three inches. She said she was not dressed and to come back. Coulter told her they would wait. After waiting two to three minutes, Coulter went to the basement apartment of the caretakers, Louis and Margaret Meidlinger, and asked to use the phone to call the bureau. He quickly returned to Cummings, and the two of them waited for Frechette to open the door. Van Meter then appeared in the hall and asked Coulter if his name was Johnson. Coulter said it was not, and as Van Meter passed on to the landing of the third floor, Coulter asked him for a name. Van Meter replied, “I am a soap salesman.” Asked where his samples were, Van Meter said they were in his car. Coulter asked if he had any credentials. Van Meter said “no,” and continued down the stairs. Coulter waited 10 to 20 seconds, then followed Van Meter. As Coulter got to the lobby on the ground floor, Van Meter opened fire on him.[27] Coulter hastily fled outside, chased by Van Meter. Eventually, Van Meter ran back into the front entrance.

Recognizing Van Meter, Nalls pointed out the Ford to Coulter and told him to disable it. Coulter shot out the rear left tire. While Coulter stayed with Van Meter’s Ford, Nalls went to the corner drugstore and called first the local police, then the bureau’s St. Paul office, but could not get through because both lines were busy.[28][29] Van Meter, meanwhile, escaped by hopping on a passing coal truck.[30]

Frechette, in her harboring trial testimony, said that she told Dillinger that the police had showed up after speaking to Cummings. Upon hearing Van Meter firing at Coulter, Dillinger opened fire through the door with a Thompson submachine gun, sending Cummings scrambling for cover. Dillinger then stepped out and fired another burst at Cummings. Cummings shot back with a revolver, but quickly ran out of ammunition. He hit Dillinger in the left calf with one of his five shots. He then hastily retreated down the stairs to the front entrance.[31] Once Cummings retreated, Dillinger and Frechette hurried down the stairs, exited through the back door and drove away in the Hudson.

The couple drove to the apartment of Eddie Green at 3300 South Fremont in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Green called his associate Dr. Clayton E. May at his office in Minneapolis, 712 Masonic Temple (still extant). With Green, his wife Beth, and Frechette following in Green’s car, Dr. May drove Dillinger to 1835 Park Avenue, Minneapolis, to the apartment of Augusta Salt, who had been providing nursing services and a bed for May’s illicit patients for several years, patients he could not risk seeing at his regular office. May treated Dillinger’s wound with antiseptics. Eddie Green visited Dillinger on Monday, April 2, just hours before Green would be mortally wounded by the FBI in St. Paul. Dillinger convalesced at Dr. May’s for five days, until Wednesday, April 4. Dr. May was promised $500 for his services, but received nothing.

Return to Mooresville

After leaving Minneapolis, Dillinger and Billie traveled to Mooresville to visit Dillinger’s father. Friday, April 6 was spent contacting family members, particularly his half-brother Hubert Dillinger. On April 6, Hubert and Dillinger left Mooresville at about 8:00 p.m. and proceeded to Leipsic, Ohio (approximately 210 miles away), to see Joseph and Lena Pierpont, Harry’s parents. The Pierponts were not home, so the two headed back to Mooresville around midnight.[34]

On April 7 at approximately 3:30 a.m., they rammed a car driven by Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Manning near Noblesville, Indiana, after Hubert fell asleep behind the wheel. They crashed through a farm fence and about 200 feet into the woods. Both men made it back to the Mooresville farm. Swarms of police showed up at the accident scene within hours. Found in the car were maps, a machine gun magazine, a length of rope, and a bullwhip. According to Hubert, his brother planned to pay a visit with the bullwhip to his former one-armed “shyster” lawyer at Crown Point, Joseph Ryan, who had run off with his retainer after being replaced by Louis Piquett.[citation needed]

At about 10:30 a.m. on April 7, Billie, Hubert and Hubert’s wife purchased a black four-door Ford V8, registering it in the name of Mrs. Fred Penfield (Billie Frechette). At 2:30 p.m., Billie and Hubert picked up the V8 and returned to Mooresville.[citation needed]

On Sunday, April 8, the Dillingers enjoyed a family picnic while the FBI had the farm under surveillance nearby.[34] Later in the afternoon, suspecting they were being watched (agents J. L. Geraghty and T. J. Donegan were cruising in the vicinity in their car), the group left in separate cars. Billie drove the new Ford V8, with two of Dillinger’s nieces, Mary Hancock in the front seat and Alberta Hancock in the back. Dillinger was on the floor of the car. He was later seen, but not recognized, by Donegan and Geraghty. Eventually, Norman, driving the V8, proceeded with Dillinger and Billie to Chicago, where they separated from Norman.[34]

The following afternoon, Monday, April 9, Dillinger had an appointment at a tavern at 416 North State Street. Sensing trouble, Billie went in first. She was promptly arrested by agents, but refused to reveal Dillinger’s whereabouts. Dillinger was waiting in his car outside the tavern and then drove off unnoticed.[35] The two would never see each other again.[citation needed]

Dillinger reportedly became despondent after Billie was arrested. The other gang members tried to talk to him out of rescuing her, but Van Meter knew where they could find bulletproof vests. That Friday morning, late at night, Dillinger and Van Meter took Warsaw, Indiana police officer Judd Pittenger hostage. They marched him at gunpoint to the police station, where they stole several more guns and bulletproof vests. After separating, Dillinger picked up Hamilton, who was recovering from the Mason City robbery. The two then traveled to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where they visited Hamilton’s sister Anna Steve.[citation needed]

Hiding in Chicago[edit]

By July 1934, Dillinger had dropped completely out of sight, and the federal agents had no solid leads to follow. He had, in fact, drifted into Chicago where he went under the alias of Jimmy Lawrence, a petty criminal from Wisconsin who bore a close resemblance to Dillinger. Working as a clerk, Dillinger found that, in a large metropolis like Chicago, he was able to lead an anonymous existence for a while. What he did not realize was that the center of the federal agents’ dragnet happened to be Chicago. When the authorities found Dillinger’s blood-spattered getaway car on a Chicago side street, they were positive that he was in the city.[8]

Dillinger had always been a fan of the Chicago Cubs, and instead of lying low like many criminals on the run, he attended Cubs games at Wrigley Field during June and July.[36] He’s known to have been at Wrigley on Friday, June 8, only to watch his beloved Cubs lose to Cincinnati 4-3. Also in attendance at the game were Dillinger’s lawyer, Louis Piquett, and Captain John Stege of the Dillinger Squad.

Plastic surgery

According to Art O’Leary, as early as March 1934, Dillinger expressed an interest in plastic surgery and had asked O’Leary to check with Piquett on such matters. At the end of April, Piquett paid a visit to his old friend Dr. Wilhelm Loeser. Loeser had practiced in Chicago for 27 years before being convicted under the Harrison Narcotic Act in 1931. He was sentenced to three years at Leavenworth, but was paroled early on December 7, 1932, with Piquett’s help.[citation needed] He later testified that he performed facial surgery on himself and obliterated the fingerprint impressions on the tips of his fingers by the application of a caustic soda preparation. Piquett said Dillinger would have to pay $5,000 for the plastic surgery: $4,400 split between Piquett, Loeser and O’Leary, and $600 to Dr. Harold Cassidy, who would administer the anaesthetic. The procedure would take place at the home of Piquett’s longtime friend, 67-year-old James Probasco, at the end of May.[citation needed]

On May 28, Loeser was picked up at his home at 7:30 p.m. by O’Leary and Cassidy. The three of them then drove to Probasco’s place. Dillinger chose to have a general anaesthetic. Loeser later testified:

I asked him what work he wanted done. He wanted two warts (moles) removed on the right lower forehead between the eyes and one at the left angle, outer angle of the left eye; wanted a depression of the nose filled in; a scar; a large one to the left of the median line of the upper lip excised, wanted his dimples removed and wanted the angle of the mouth drawn up. He didn’t say anything about the fingers that day to me.[38]

Cassidy administered an overdose of ether, which caused Dillinger to suffocate. He began to turn blue and stopped breathing. Loeser pulled Dillinger’s tongue out of his mouth with a pair of forceps, and at the same time forcing both elbows into his ribs. Dillinger gasped and resumed breathing. The procedure continued with only a local anaesthetic. Loeser removed several moles on Dillinger’s forehead, made an incision in his nose and an incision in his chin and tied back both cheeks.[citation needed]

Loeser met with Piquett again on Saturday, June 2, with Piquett saying that more work was needed on Dillinger and that Van Meter now wanted the same work done to him. Also, both now wanted work done on their fingertips. The price for the fingerprint procedure would be $500 per hand or $100 a finger. Loeser used a mixture of nitric and hydrochloric acid—commonly known as aqua regia.[39][page needed]

Loeser met O’Leary the following night at Clark and Wright at 8:30, and they once again drove to Probasco’s. Present this evening were Dillinger, Van Meter, Probasco, Piquett, Cassidy, and Peggy Doyle, Probasco’s girlfriend. Loeser testified that he worked for only about 30 minutes before O’Leary and Piquett had left.

Loeser testified:

Cassidy and I worked on Dillinger and Van Meter simultaneously on June 3. While the work was being done, Dillinger and Van Meter changed off. The work that could be done while the patient was sitting up, that patient was in the sitting-room. The work that had to be done while the man was lying down, that patient was on the couch in the bedroom. They were changed back and forth according to the work to be done. The hands were sterilized, made aseptic with antiseptics, thoroughly washed with soap and water and used sterile gauze afterwards to keep them clean. Next, cutting instrument, knife was used to expose the lower skin…in other words, take off the epidermis and expose the derma, then alternately the acid and the alkaloid was applied as was necessary to produce the desired results.[40]

Minor work was done two nights later, Tuesday, June 5. Loeser made some small corrections first on Van Meter, then Dillinger. Loeser stated:

A man came in before I left, who I found out later was Baby Face Nelson. He came in with a drum of machine gun bullets under his arm, threw them on the bed or the couch in the bedroom, and started to talk to Van Meter. The two then motioned for Dillinger to come over and the three went back into the kitchen.

Peggy Doyle later told agents:

Dillinger and Van Meter resided at Probasco’s home until the last week of June 1934; that on some occasions they would be away for a day or two, sometimes leaving separately, and on other occasions together; that at this time Van Meter usually parked his car in the rear of Probasco’s residence outside the back fence; that she gathered that Dillinger was keeping company with a young woman who lived on the north side of Chicago, inasmuch as he would state upon leaving Probasco’s home that he was going in the direction of Diversey Boulevard; that Van Meter apparently was not acquainted with Dillinger’s friend, and she heard him warning Dillinger to be careful about striking up acquaintances with girls he knew nothing about; that Dillinger and Van Meter usually kept a machine gun in an open case under the piano in the parlor; that they also kept a shotgun under the parlor table.[41]

O’Leary stated that Dillinger expressed dissatisfaction with the facial work that Loeser had performed on him. O’Leary said that, on another occasion, “that Probasco told him, ‘the son of a bitch has gone out for one of his walks’; that he did not know when he would return; that Probasco raved about the craziness of Dillinger, stating that he was always going for walks and was likely to cause the authorities to locate the place where he was staying; that Probasco stated frankly on this occasion that he was afraid to have the man around.”[citation needed]

Agents arrested Loeser at 1127 South Harvey, Oak Park, Illinois, on Tuesday, July 24. O’Leary returned from a family fishing trip on July 24, the day of Loeser’s arrest, and had read in the newspapers that the Department of Justice was looking for two doctors and another man in connection with some plastic work that was done on Dillinger. O’Leary left Chicago immediately, but returned two weeks later, learned that Loeser and others had been arrested, phoned Piquett, who assured him everything was all right, then left again. He returned from St. Louis on August 25 and was promptly taken into custody.[42]

On Friday, July 27, Jimmy Probasco jumped or “accidentally” fell to his death from the 19th floor of the Bankers’ Building in Chicago while in custody.[citation needed]

On Thursday, August 23, Homer Van Meter was shot and killed in a dead-end alley in St. Paul by Tom Brown, former St. Paul Chief of Police, and then-current chief Frank Cullen.[citation needed]

Polly Hamilton, Dillinger’s last girlfriend[edit]

Rita “Polly” Hamilton was a teenage runaway from Fargo, North Dakota.[6] She met Ana Ivanova Akalieva- Ana Cumpănaş(aka Ana Sage) in Gary, Indiana, and worked periodically as a prostitute (in Anna’s brothel) until marrying Gary police officer Roy O. Keele in 1929.[6] They later divorced in March 1933.[6]

In the summer of 1934, the now twenty-six-year-old[1] Hamilton was a waitress in Chicago at the S&S Sandwich Shop located at 1209 ½ Wilson Avenue. She had remained friends with Sage and was sharing living space with Sage and Sage’s twenty-four-year-old son, Steve, at 2858 Clark Street.[6]

Dillinger and Hamilton, a Billie Frechette look-a-like,[1][6] met in June 1934 at the Barrel of Fun night club located at 4541 Wilson Avenue. Dillinger introduced himself as Jimmy Lawrence and said he was a clerk at the Board of Trade.[6] They dated until Dillinger’s death at the Biograph Theater in July 1934.[1][6]

Informant betrays Dillinger[edit]

Division of Investigations chief J. Edgar Hoover created a special task force headquartered in Chicago to locate Dillinger. On July 21, Ana Cumpănaș (a/k/a Anna Sage), a madam from a brothel in Gary, Indiana, also known as “The Woman in Red” contacted the FBI. She was a Romanian immigrant threatened with deportation for “low moral character”[43] and offered agents information on Dillinger in exchange for their help in preventing her deportation. The FBI agreed to her terms, but she was later deported nonetheless. Cumpănaş revealed that Dillinger was spending his time with another prostitute, Polly Hamilton, and that she and the couple would be going to see a movie together on the following day. She agreed to wear an orange dress,[44] so police could easily identify her. She was unsure which of two theaters they would be attending, the Biograph or the Marbro.[8] On December 15, 1934, pardons were issued by Indiana Governor Harry G. Leslie for the offenses of which Anna Sage was convicted.[45]

Sage stated that on Sunday afternoon, July 22, Dillinger asked her if she wanted to go to the show with them, he and Polly.

She asked him what show was he going to see, and he said he would ‘like to see the theater around the corner,’ meaning the Biograph Theater. She stated she was unable to leave the house to inform Purvis or Martin about Dillinger’s plans to attend the Biograph, but as they were going to have fried chicken for the evening meal, she told Polly she had nothing in which to fry the chicken, and was going to the store to get some butter; that while at the store she called Mr. Purvis and informed him of Dillinger’s plans to attend the Biograph that evening, at the same time obtaining the butter. She then returned to the house so Polly would not be suspicious that she went out to call anyone.

The crowd at Chicago’s Biograph Theater on July 22, 1934, shortly after John Dillinger was killed there by law enforcement officers.

A team of federal agents and officers from police forces from outside of Chicago was formed, along with a very small number of Chicago police officers. Among them was Sergeant Martin Zarkovich, the officer to whom Sage had acted as an informant. At the time, federal officials felt that the Chicago police had been compromised and therefore could not be trusted; Hoover and Purvis also wanted more of the credit.[44] Not wanting to take the risk of another embarrassing escape of Dillinger, the police were split into two groups. On Sunday, one team was sent to the Marbro Theater on the city’s west side, while another team surrounded the Biograph Theater at 2433 N. Lincoln Avenue on the north side.[8]

Death and Shooting at the Biograph Theater[edit]

FBI photograph of the Biograph Theater taken July 28, 1934, six days after the shooting, the only night Murder in Trinidad played[46]

A Dillinger death maskmade from an original mold, and eyebrow hair, on display at the Crime Museum in Washington, D.C. Note the bullet exit mark below the right eye.

Grave at Crown Hill Cemetery, Indianapolis, Indiana; at least the fourth marker to be replaced since 1934, due to souvenir seekers chipping away at them

Sage, Hamilton, and Dillinger were observed entering the Biograph at approximately 8:30 p.m.,[4][45][47] which was showing a crime drama Manhattan Melodrama, starring Clark Gable, Myrna Loy and William Powell. During the stakeout, the Biograph’s manager thought the agents were criminals setting up a robbery. He called the Chicago police, who dutifully responded and had to be waved off by the federal agents, who told them that they were on a stakeout for an important target.[8]

When the film ended, Purvis[48] stood by the front door and signaled Dillinger’s exit by lighting a cigar. Both he and the other agents reported that Dillinger turned his head and looked directly at the agent as he walked by, glanced across the street, then moved ahead of his female companions, reached into his pocket but failed to extract his gun,[6]:353 and ran into a nearby alley.[44] Other accounts stated Dillinger ignored a command to surrender, whipped out his gun, then headed for the alley. Agents already had the alley closed off, but Dillinger was determined to shoot it out.[49]

Three men pursued Dillinger into the alley and fired. Clarence Hurt shot twice, Charles Winstead three times, and Herman Hollis once. Dillinger was hit from behind and fell face first to the ground.[50]

Dillinger was struck four times, with two bullets grazing him and one causing a superficial wound to the right side. The fatal bullet entered through the back of his neck, severed the spinal cord, passed into his brain and exited just under the right eye, severing two sets of veins and arteries.[3] An ambulance was summoned, although it was soon apparent Dillinger had died from the gunshot wounds; he was officially pronounced dead at Alexian Brothers Hospital.[8][50] According to investigators, Dillinger died without saying a word.[51]

Two female bystanders, Theresa Paulas and Etta Natalsky, were wounded. Dillinger bumped into Natalsky just as the shooting started.[34][44] Natalsky was shot and was subsequently taken to Columbus Hospital.[52] Winstead was later thought to have fired the fatal shot, and as a consequence received a personal letter of commendation[specify] from J. Edgar Hoover.[44]

Dillinger was shot and killed by the special agents on July 22, 1934,[4][53][54] at approximately 10:40 p.m, according to a New York Times report the next day.[47]Dillinger’s death came only two months after the deaths of fellow notorious criminals Bonnie and Clyde.There were reports of people dipping their handkerchiefs and skirts into the pool of blood that had formed, as Dillinger lay in the alley, as keepsakes.[citation needed]

Aftermath[edit]

Dillinger’s body was available for public display at the Cook County morgue.[55]An estimated 15,000 people viewed the corpse over a day and a half. As many as four death masks were also made.[56]

Dillinger’s gravestone has been replaced several times because of vandalism by people chipping off pieces as souvenirs.[57] Hilton Crouch (1903-1976), an associate of Dillinger’s on some early heists, is buried only a few yards to the west.

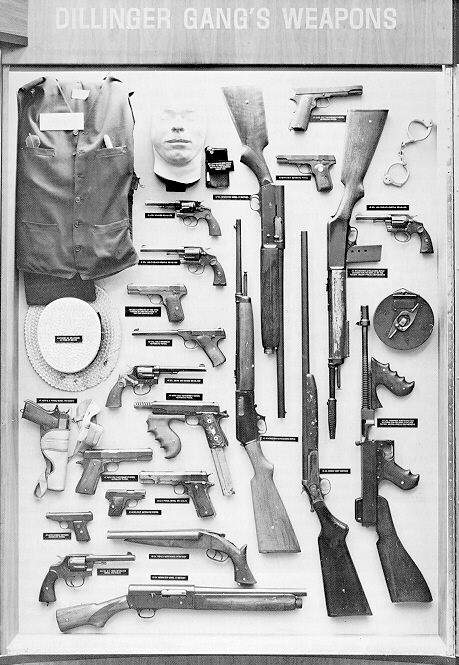

His Fully Automatic 45.

His Fully Automatic 45.

His Gangs Guns

Thats a lot of Firepower there!

Thats a lot of Firepower there!

NSFW Stuff

There is an Old Urban Legend that Old John was a very well endowed kinda of a Guy. Due in part to this photo. Myth has it that after his demise. It was removed and sent to the Smithsonian in a jar with preservative fluid.

Obviously some folks believed this!

Courage & Money are the only two things that never go out of fashion!

Courage & Money are the only two things that never go out of fashion! Nothing lasts as Friends & Good Relatives always disappear!

Nothing lasts as Friends & Good Relatives always disappear!