Category: Manly Stuff

Written over 3,000 years ago, the ancient adage “Iron sharpens iron” is traditionally attributed to King Solomon via the Book of Proverbs. (Proverbs 27:17)

The imagery reflects ancient blacksmithing practices where one iron tool was used to file, hone, or carve an edge on another. In traditional wisdom, it symbolizes mutual improvement, constructive challenge and character development through community.

Today, elite athletes, shooters, martial artists and warfighters use this same concept to make themselves better prepared for engagement with others. When applied to self-defense, there are three such pieces of iron that can be used in developing your skills to survive a violent physical altercation. What are these three and how can you use them to both sharpen your skills and strengthen your resolve?

The First

The first piece of iron is discipline, where you challenge yourself. Some people say follow your passion; others say find your motivation. Even if you can somehow muster both, when passion eventually wanes, and motivation dissipates, all that remains is discipline. In the long run, long after emotions fade, discipline will carry you the distance.

Discipline isn’t something you’re born with; it’s something you earn through consistent, intentional action. Its potential is available to all of us, but it is made manifest by those completing two halves.

In shooting and defensive tactics, discipline begins with a clear purpose: a goal strong enough to push you forward when motivation evaporates. From there, it’s forged through repetition. Showing up to practice, completing each drill with intent, and maintaining the fundamentals even when no one is watching gradually hard-wires discipline into behavior. Over time, these daily choices turn into personal habits. What once required effort becomes unconscious competence.

The other half of discipline comes from environment and accountability.

Training partners, coaches, and teammates create pressure and support that sharpen your performance. They leverage mistakes, raise expectations, and challenge you to raise the bar. Through this process, you learn to become comfortable being uncomfortable and act with purpose instead of emotion. Discipline fully develops when you repeatedly choose the long-term result over short-term gratification, until that choice becomes part of who you are.

The Next Step

Next is being challenged by others. Placing yourself in a competitive environment will expose the gaps you didn’t know you had. Whether it’s sparring rounds, timed drills on the range, rolling on the mat, or pressure-based scenario work, competition forces you to confront reality. You learn very quickly what holds up under stress and what falls apart the moment adrenaline or uncertainty shows up.

Other people, especially those who are more skilled and experienced, become the second piece of iron. Their presence pushes you to elevate your performance, tighten your fundamentals, and lose the excuses. When you face someone who gives you honest resistance, you sharpen not only your technique but your mental game, adapting in real time and discovering a higher gear you didn’t know you had.

This type of challenge is not about ego; it’s about exposure and growth. Controlled pressure reveals weaknesses so you can address them before they become liabilities in real-world conditions.

When you’ve hammered the rounds with people who can push you to your limits, when you’ve performed under watchful eyes or against the clock, you develop a calmness that only earned experience can create.

You learn to stay composed, think clearly, and execute under pressure because you’ve already faced environments that demanded it. Confidence is the sharpening effect of this second iron: the honest challenge of others who make you better by refusing to go easy on you.

Where It Counts

The third piece of iron is adversity itself: the unexpected, the uncomfortable, and the uncontrollable. While discipline builds your foundation and other people refine your skill, real adversity is what hardens you. This includes training sessions where everything feels off, drills you fail repeatedly, physical fatigue that tests your will, or situations where stress and uncertainty overwhelm your plan “A”.

Most people tend to avoid adversity, but in self-defense and performance shooting, adversity is the most legit instructor you’ll ever have. When things do not go your way, when the environment is chaotic or stacked against you, that struggle forces adaptation. It teaches resilience, problem-solving under duress and the ability to regain composure when the situation is anything but comfortable.

Adversity sharpens you by stripping away what doesn’t work. Under stress, you can’t BS your way through or negotiate with reality. You must respond. You discover your real thresholds, your real habits, and your real mental focus.

Over time, facing adversity builds a deep, internal confidence: not the kind based on perfect conditions, but the kind rooted in having survived and adapted to imperfect ones. In self-defense, this matters more than any drill or trophy.

Conclusion

Violence is chaotic, unfair, and unfolds fast. The person who has trained through adversity, who has stumbled, adjusted, and kept moving, is the person far more likely to stay in the fight when it counts. This final piece of iron ensures that when life hits back, you don’t break; you respond with resilience and skill.

The ancient Spartans viewed adversity as a gift from the gods. Hardship was seen as the raw material from which strength and courage were shaped. They believed that only through struggle could a warrior discover their true limits and expand them. Comfort softened a person; adversity revealed them. Every challenge, every setback, every grueling test was considered an opportunity to strip away weakness and build a level of resilience that couldn’t be taught any other way. It runs parallel to the U.S.M.C. mantra, “Pain is weakness leaving the body.”

To our ancestors, iron sharpening iron wasn’t something to endure reluctantly, but a divine gift to willingly embrace. It was the crucible that burned away hesitation and fear, leaving behind the disciplined, skilled and unshakeable. It was what made you worthy of the shield you carried and the trust of those you protected.

FORT BRAGG, N.C. – From Europe to North Africa to the Pacific, U.S. Army Rangers played a crucial role in many of World War II’s most pivotal moments, laying down roots for today’s 75th Ranger Regiment. At the onset of the war, the Army had no units capable of performing specialized commando missions. By the end of the war, the Army had fielded seven Ranger battalions, beginning with the activation of the 1st Ranger Battalion in Northern Ireland on June 19, 1942.

Major William O. Darby, an artillery officer, was hand-picked to recruit volunteers for the battalion, designed to replicate the capability of British commandos. The volunteers underwent a strenuous selection program to identify and train the best candidates. On Aug. 19, 1942, 50 of these specially selected soldiers participated in Operation Jubilee, a Canadian-led amphibious assault on the English Channel port of Dieppe, France. The Rangers helped destroy one of the enemy batteries, at the cost of three of their own. Following the raid, the 1st Ranger Battalion participated in the U.S.-led invasion of North Africa.

In the early morning hours of Nov. 8, 1942, Operation Torch commenced with attacks on the Algerian port in Arzew. As two Ranger companies led by Maj. Herman Dammer assaulted the port, three others led by Darby assaulted enemy cannons overlooking the harbor, capturing them within 15 minutes. Two Rangers died and eight were wounded during the action, but the Rangers’ success helped the Allies secure a foothold on the continent.

The 29th Ranger Battalion (Provisional) was formed on Dec. 20, 1942 in England. The volunteers came from the 29th Infantry Division. Attached to British commandos for additional training, several of the Rangers from the 29th participated in combat raids and reconnaissance missions into Norway before being disbanded on Oct. 15, 1943.

The 1st Ranger Battalion’s encouraging performance in Africa led the Army in 1943 to activate four more Ranger Battalions – the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th. Attached to the 1st Infantry Division of Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s U.S. Seventh Army, Darby led a Ranger Force consisting of the 1st, 3rd, and 4th Ranger battalions that spearheaded Operation Husky, the American landings in Sicily on July 10, 1943.

With Sicily secured, the Rangers turned their attention to mainland Italy and Operation Avalanche. Before daylight on Sept. 9, 1943, the Ranger Force hit the beach west of Salerno on the far-left flank of the Allied landing. The 4th Battalion, led by Maj. Roy Murray, quickly secured the beach, and cleared the way for the 1st and 3rd battalions to move inland. The Rangers rapidly gained their objectives by midmorning of the first day. The Ranger Force later participated in the Anzio operation, where they conducted a daring but ill-fated raid into the Italian town of Cisterna on January 30, 1944.

The 2nd and 5th entered the war on June 6, 1944, on the beaches of Normandy, France, during Operation Overlord. Three companies of 2nd Battalion Rangers, led by Lt. Col. James E. Rudder, daringly scaled the cliffs of Pointe du Hoc, overlooking Omaha Beach, to destroy German gun emplacements targeting troops landing on the beachhead. Meanwhile, the remainder of 2nd Battalion and the entirety of 5th Ranger Battalion fought their way ashore Omaha Beach alongside the 1st and 29th Infantry Division. The D-Day missions earned the Rangers their motto, “Rangers, lead the way!” The 2nd and 5th Rangers fought in the Allied campaign in western Europe until the end of the war.

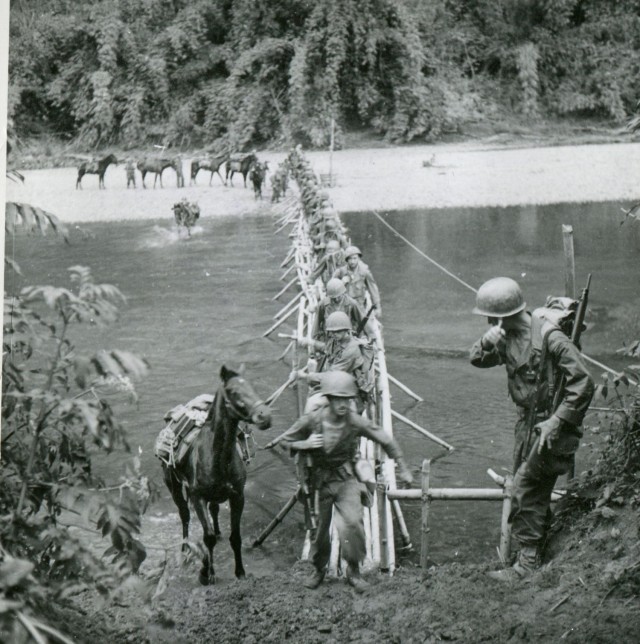

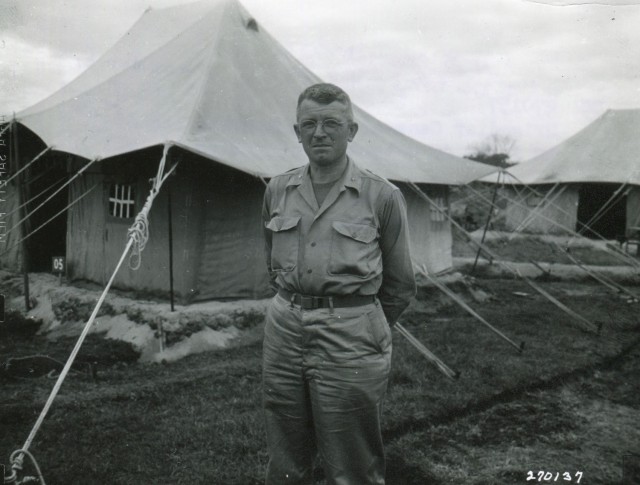

In the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations, another legendary Ranger lineage unit was organized on Oct. 3, 1943: the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional). Better known as “Merrill’s Marauders” after its commander, Brig. Gen. Frank D. Merrill, the 5307th, a Long-Range Penetration Group, fought a grueling campaign in the mountainous jungles of Burma that lasted until mid-1944. Following the capture of Myitkyina, Burma, the remnants of the 5307th were consolidated with the 475th Infantry Regiment on Aug. 10, 1944. The 475th was part the second Long Range Penetration Group formed for service in Burma, the 5332nd Brigade (Provisional). Better known as the MARS Task Force, the 5332nd helped secure the last stretches of the Burma Road remaining in Japanese hands, before moving on to service in China.

In mid-1944, one more Ranger Battalion was activated, with the mission of supporting U.S. Sixth Army operations in the Southwest Pacific. Lieutenant Colonel Henry A. Mucci was selected to organize, train, and command the 6th Ranger Battalion, which was formed out of the 98th Field Artillery Battalion, the 6th Rangers played a prominent role in the recapture of the Philippines, starting with the amphibious assault on Leyte in October 1944. On neighboring Luzon, in January 1945, Company A, 6th Rangers, supported by the Sixth Army Special Reconnaissance Unit, also known as the “Alamo Scouts,” and Philippine guerrillas, executed its most famous action when it raided a Japanese Prisoner-of-War camp near Cabanatuan, Philippines. Against overwhelming odds, the operation freed more than five hundred Allied prisoners.

It’s for these and many other actions that the Ranger units of World War II would go on to earn multiple unit citations prior to being disbanded in 1945. Their legacy endured long beyond the war, with their courage and audacity setting the example for future generations of U.S. Army Rangers.

To learn more about the U.S. Army Rangers of World War II, go to arsof-history.org.

Well I thought it was funny!

Robert Downey, Jr. is one of the most esteemed actors of his generation. His depiction of Tony Stark as Iron Man across 10 big-budget superhero movies became iconic. I once read a commentary by a British film critic who said that Downey’s English accent in the Sherlock Holmes films was the only example of an American playing a Brit that he felt was in any way believable. What makes that so remarkable is that Downey never took acting lessons. He just got in front of the camera and did his thing. He’s a natural.

There was a time when this was the rule rather than the exception. John Wayne’s natural swagger certainly could not be learned. Back in the Golden Age of Hollywood, actors were not necessarily mushy, fragile prima donnas. They often were drawn from the ranks of truly manly men out in the real world. Principle among them was one Peter Ortiz.

Filmography of a Hero

Peter Ortiz starred in 27 films and two television series. His filmography includes such classics as She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Retreat, Hell!, The Outcast, Twelve O’Clock High, Wings of Eagles, and Rio Grande. Ortiz brought a gritty realism to the sundry roles he played on screens both large and small. That’s because he was arguably the baddest man ever to grace the silver screen.

Pierre Julien Ortiz was born in New York in 1913. His mother was of Swiss stock, while his dad was a Spaniard born in France. He was educated at the French University of Grenoble. Ortiz spoke 10 languages. In 193,2 at age 18, he joined the French Foreign Legion.

The Foreign Legion is comprised of some legendarily rough hombres. Peter Ortiz thrived in this space. He earned the Croix de Guerre twice while fighting the Riffian people in Morocco. In 1935, Ortiz turned down a commission as an officer in the Legion to travel to Hollywood and serve as a technical advisor for war films.

Proper War

We modern Americans often overlook this fact, but World War II burned on for a couple of years before we got involved. As soon as the shooting started, Ortiz left Hollywood and returned to the Legion as a sergeant. He soon earned a battlefield commission and was wounded while destroying a German fuel dump. He was captured soon thereafter but escaped through Portugal, eventually making it back to the United States.

War was a growth industry in the early 1940s, and American citizens with combat experience were invaluable assets. Ortiz enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps in June of 1942 and earned a commission as a Second Lieutenant 40 days later. He made captain by year’s end and was deployed to Tangier, Morocco, assigned to the Office of Strategic Services. The OSS was the predecessor to the CIA. Captain Peter Ortiz was now officially a spy.

Undercover Ops

Ortiz was wounded badly, recovered, and then parachuted into occupied Europe several times. He repatriated downed Allied flyers and helped organize French Underground units. In August 1944, he was captured by the Germans. He survived torture by the Gestapo and somehow avoided execution. In April 1945, Ortiz’s POW camp was liberated. Now a Lieutenant Colonel, he made his way back to Hollywood to pick up where he left off.

In 1954, Southeast Asia was heating up, so Lt. Ortiz volunteered to return to active duty. However, by then, he was more than 40 years old and sort of famous. The Marines turned him down but promoted him to full Colonel in retirement.

Decorations

We’ve glossed over this guy’s amazing career. He was awarded an Order of the British Empire (OBE) by the government of England. He earned both the Navy Cross and the Purple Heart, each twice. The Navy Cross is our second-highest award for valor, right after the Medal of Honor. Here’s an excerpt from his first Navy Cross citation:

“Operating in civilian clothes and aware that he would be subject to execution in the event of his capture, Major Ortiz parachuted from an airplane with two other officers of an Inter-Allied mission to reorganize existing Maquis groups in the region of Rhone.

By his tact, resourcefulness and leadership, he was largely instrumental in affecting the acceptance of the mission by local resistance leaders, and also in organizing parachute operations for the delivery of arms, ammunition and equipment for use by the Maquis in his region.

Although his identity had become known to the Gestapo with the resultant increase in personal hazard, he voluntarily conducted to the Spanish border four Royal Air Force officers who had been shot down in his region, and later returned to resume his duties. Repeatedly leading successful raids during the period of this assignment, Major Ortiz inflicted heavy casualties on enemy forces greatly superior in number, with small losses to his own forces.”

Ruminations

There were two Hollywood films that were based upon his personal adventures. 13 Rue Madeleine came out in 1947. Operation Secret hit theaters in 1952. Ortiz had one son, Pete Junior, who served as a Marine officer himself, retiring as a Lieutenant Colonel.

Of his dad, the younger Marine said, “My father was an awful actor, but he had great fun appearing in movies.” Colonel Peter Ortiz might not have been the greatest actor of all time, but he was an amazing warrior.

United States

Navy Cross with gold star

Navy Cross with gold star

Legion of Merit

Legion of Merit Purple Heart with gold star

Purple Heart with gold star

American Campaign Medal

American Campaign Medal European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal

European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal World War II Victory Medal

World War II Victory Medal Marine Corps Reserve Ribbon

Marine Corps Reserve Ribbon Parachutist Badge

Parachutist Badge

United Kingdom

Officer of the Order of the British Empire

Officer of the Order of the British Empire

France

Chevalier of the Legion of Honor

Chevalier of the Legion of Honor Médaille militaire

Médaille militaire Croix de guerre des théâtres d’opérations extérieures with bronze and silver stars

Croix de guerre des théâtres d’opérations extérieures with bronze and silver stars Croix de Guerre 1939-1945 with two bronze palms and silver star

Croix de Guerre 1939-1945 with two bronze palms and silver star Croix du combattant

Croix du combattant Médaille des Évadés

Médaille des Évadés Médaille Coloniale with the campaign clasp: “MAROC”

Médaille Coloniale with the campaign clasp: “MAROC” Médaille des Blesses

Médaille des Blesses 1939–1945 Commemorative war medal (France)

1939–1945 Commemorative war medal (France)

.PNG)