Category: Manly Stuff

Our Great Kids!!!!!!!

.jpeg)

“Leadership is the art of accomplishing more than the science of management says is possible.”

This is one of many quotes attributed to legendary public statesman and former Secretary of State Colin Powell.

Since his retirement from public office in 2004, Powell has spent much of his time sharing his leadership knowledge with the business community. In his 2012 book, It Worked For Me, Powell attributes his success to hard work, straight talk, respect for others, and thoughtful analysis.

At the heart of the book are Powell’s “13 Rules” — ideas that he gathered over the years that formed the basis of his leadership principals.

Powell’s 13 Rules are listed below. They are full of emotional intelligence and wisdom for any leader.

1. It Ain’t as Bad as You Think! It Will Look Better in the Morning. Leaving the office at night with a winning attitude affects more than you alone; it conveys that attitude to your followers.

2. Get Mad Then Get Over It. Instead of letting anger destroy you, use it to make constructive change.

3. Avoid Having Your Ego so Close to your Position that When Your Position Falls, Your Ego Goes With It. Keep your ego in check, and know that you can lead from wherever you are.

4. It Can be Done. Leaders make things happen. If one approach doesn’t work, find another.

5. Be Careful What You Choose. You May Get It. Your team will have to live with your choices, so don’t rush.

6. Don’t Let Adverse Facts Stand in the Way of a Good Decision. Superb leadership is often a matter of superb instinct. When faced with a tough decision, use the time available to gather information that will inform your instinct.

7. You Can’t Make Someone Else’s Choices. You Shouldn’t Let Someone Else Make Yours. While good leaders listen and consider all perspectives, they ultimately make their own decisions. Accept your good decisions. Learn from your mistakes.

8. Check Small Things. Followers live in the world of small things. Find ways to get visibility into that world.

9. Share Credit. People need recognition and a sense of worth as much as they need food and water.

10. Remain calm. Be kind. Few people make sound or sustainable decisions in an atmosphere of chaos. Establish a calm zone while maintaining a sense of urgency.

11. Have a Vision. Be Demanding. Followers need to know where their leaders are taking them and for what purpose. To achieve the purpose, set demanding standards and make sure they are met.

12. Don’t take counsel of your fears or naysayers. Successful organizations are not built by cowards or cynics.

13. Perpetual optimism is a force multiplier. If you believe and have prepared your followers, your followers will believe.

Colin Powell’s rules are short but powerful. Use them as a reminder to manage your emotions, model the behavior you want from others, and lead your team through adversity.

Rest in Eternal Peace, General!

Thank you for your service to the United States, the world, and Mankind.

The world is a better place for you having been in it for 84 years.

Godspeed!

Once, I Was a Peace Advocate. Now, I Have No Idealism Left.

After terrorists killed my cousin Daniel Pearl, my family called for peace. But after the worldwide celebration of our people’s slaughter, my hope for peace is dead.

The story I’m about to tell is one that many progressive Jews can relate to. In some ways, it’s a prototypical arc of a diaspora Jew who has always advocated for nuance. This week, something broke in us. We watched history repeat itself. Not just on the global scale, with the wanton massacre of our people, the savage mass murders and dismemberments of entire families and communities. But for many, my family included, history is repeating itself on a personal level as well.

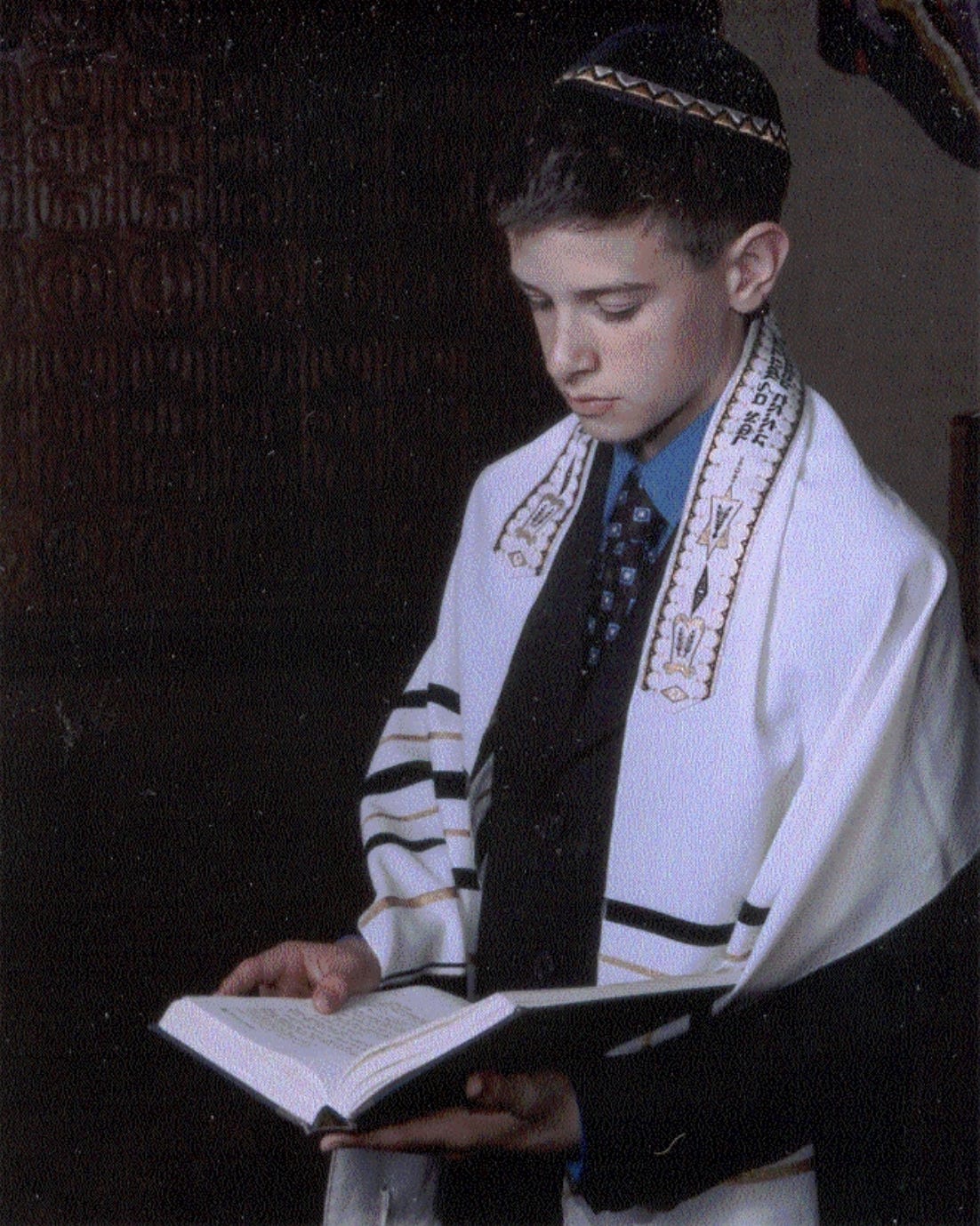

In March 2003, I turned 13 and celebrated my bar mitzvah in Walnut Creek, California. By Jewish tradition, I became a man. But the ceremony felt redundant; I had already grown up. Only one year earlier, my older cousin, Daniel Pearl, an investigative journalist for The Wall Street Journal, was kidnapped and beheaded by Islamist jihadis while on assignment in Pakistan.

His killers, like the Hamas killers of last weekend, proudly released a video documenting Danny’s murder. Among Danny’s last words were, “My father is Jewish. My mother is Jewish. I am Jewish.” At first, I was in shock—how had my own cousin become a player in such a large international nightmare? Why did people get murdered simply for being who they are? In this case, for being Jewish?

Danny’s parents did not call for revenge. Instead they set up The Daniel Pearl Foundation that offers fellowships, sponsors cross-cultural music events (Danny was a gifted musician), and brings people together to improve the world. Even after what my family had been through, their work encouraged me to be idealistic and believe that the Jewish people could make peace with our neighbors. I became a fierce advocate for peace.

When I immigrated to Israel at the age of 18 and enlisted in the Israel Defense Forces, I was still driven by ideals. I thought I could promote more goodwill with our Palestinian neighbors. Serving in a combat unit based on the Gaza border, I witnessed the release of the kidnapped Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit, held for five years by Hamas, when his freedom was exchanged for more than 1,000 Palestinian prisoners. One for 1,000. Despite my many criticisms of the Israeli government, I recognized then how much Israel valued the life of every soldier.

On my rare free weekend, I spent my time at Kibbutz Be’eri. Because I was a “lone soldier”—that is, an immigrant without much close family in Israel—I was given a host family. They treated me like a son, including teasing me relentlessly for choosing to come to Israel and serve, whereas most Israelis have no choice. They were politically left, just like me. Despite rockets often raining down on them, they believed in peace, just like me. This week, when the terrorists came, ideals didn’t make a difference.

I watched the news in horror as terrorists massacred over 100 people at Kibbutz Be’eri. Women. Children. I frantically messaged my host family and heard nothing back. Like my cousin Danny years ago, my family was being held hostage. The good news: unlike Danny, my host family at Kibbutz Be’eri was saved. They are physically okay. But how can they really be okay, after watching their friends and neighbors being slaughtered?

There was a time when these types of events couldn’t shake my ideals. I used to argue relentlessly for a two-state solution. I fought bitterly with Israeli friends about the decency of the Palestinian people. Even though radical Islamists had murdered my cousin, even though civilians had been blown up in buses daily during the Second Intifada, I refused to give in to nihilism.

In 2012, I returned to the States to study film at University of Southern California, and published a book about my military service that criticized the Israeli government. This didn’t win me many friends, but I continued to advocate for nuance regardless. I proudly supported Black Lives Matter, LGBTQIA+, and feminist causes. I called myself a progressive Jew.

But over the years, I noticed a disturbing trend: With all the atrocities in the world, why did my social justice warrior friends hate Israel so disproportionately? Why did it feel like intersectionality excluded Jews? Why did the left—who supposedly stood up for human rights—put child-murdering Hamas terrorists on a pedestal?

At first, I thought it must be miseducation.

“Ah, they think Palestinians are the indigenous people. I’ll show that Jewish history, and the archaeology to prove it, dates back millennia.”

“Ah, they think we’re white colonizers. I’ll show how many Jews are people of color, including those who are Mizrahi, Sephardi, and Ethiopian.”

“Ah, they’ll get it once I show them that there are fifty Muslim countries, and only one Jewish state.”

But my friends weren’t interested in correcting their misunderstandings.

I agreed that the settlements were unlawful, that Gaza was a humanitarian crisis, that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyuahu was a dictator. I assumed—if I cared enough, if I mourned for the Palestinian dead, if I put nuance above all else—our neighbors and their allies would give us the same decency.

How wrong I was. This past week, as over 1,300 Jews were slaughtered, the most murderous attack on Jews since the Holocaust, I saw the true face of Palestinians and their allies. All around the world, they celebrate. They gloat. They mock our tears. They do not protest against Hamas. They embrace pure evil.

And so, to the terrorists I now say:

When you killed my family, I forgave you. When you killed my people, I forgave you. But when you killed my idealism, I had no forgiveness left.

To non-Jewish friends who have reached out, thank you. It is simply the human thing to do. To friends who dare justify what has happened, you are not friends. You are nothing but Nazi supporters dressed up in leftist intellectual language. To the Palestinians: you have lost all moral authority to claim victimhood. I will never advocate for you again. To my family, friends in Israel, and Jews around the world hurting right now, I love you. Stay safe.

In Berlin, where I live today with my German-Ukrainian Jewish wife, Germans love to say “Never Again.” Right now, Never Again is happening again in real time, livestreamed for the whole world to see. I find myself looking up my military number in case the IDF reserves call for me. Unlike our enemy, I feel no joy at the prospect of going to war. But if our people’s existence is at stake, I will do what I must. I will be the world’s favorite villain: the Jew who has the audacity to defend his people.

Ilan Benjamin is the founder of FourFront, a social media entertainment business; an award-winning filmmaker; and the author of Masa: Stories of a Lone Soldier. Follow him on Twitter (now X): @ilanibenjamin.