Category: Interesting stuff

Every profession has “that guy” — the one who always must know the most, have the best experience, did it bigger and better and on and on and on.

It is my pleasure to greet each class on Training Day One (TD1) at Gunsite Academy. I consider it a great opportunity and honor and a highlight of my week. As we discuss the history of Gunsite, the highlights of their class, where the necessary amenities are located and more, I warn them about “that guy.”

Best Of The Best

Gunsite has some of the best instructors in the firearms training world. As our founder, the late Lt. Col. Jeff Cooper said: “They have seen the elephant.” One does not buy their way to being a Gunsite Instructor, they earn it. And it is a tough ticket to punch.

I ask the students on the first morning to keep an open mind when their instructors suggest methods of shooting to them differing from what the student currently uses. Try this stance, try this grip, let’s move your trigger finger a bit, have you considered a different firearm? The vast majority are open-minded and eager to listen to try to improve their gun handling, marksmanship and mindset.

However, we occasionally have “that guy or gal.” Gunsite Rangemaster to student: “Let’s modify your body position a bit.” Student looks at Rangemaster: “This is the way I’ve always done it.” Sigh … “Let’s modify your grip a bit.” Student: “This is the way my grandfather/dad/husband told me to do it.” Gunsite Rangemaster — How about you consider a different firearm that might fit your hand better?” “Student — “This is the gun my spouse told me to use and was best” or “This is the one the guy at the gun counter said would work well.”

As an aside — Never try to teach a family member or spouse to drive a stick shift, paddle a canoe or shoot.

Further, men should never try to purchase their lady’s gun purse, holster or firearm without them present. Find a suitable trainer and let them do it. Trust me on this …

You saved and saved your money, found the perfect firearm, picked your course, arranged for the vacation from work, purchased the plane ticket or fuel, rented a car, got the hotel, bought meals but now you want to do it “your way.” What is the point? Did you come to learn, or simply visit?

The Bottom Line

Let me make this simple — Why did you send us all the money? If you are going to do it the way you’ve always done it, why are you here? You could have stayed home and shot at soda cans out at grandpa’s farm. You really wouldn’t learn anything but you won’t here either, if you don’t let yourself.

What may have been cutting edge 15 years ago is no longer. Despite what inter web pundits say, The Modern Technique developed by Jeff Cooper 50 years ago has and continues to evolve. Techniques and technologies change, and good instructors know this and teach this.

Please heed the tried-and-true advice to “Listen and Do.”

Men — Put on your thick skin for what I am about to tell you. Women are better students than men as they truly “Listen and Do.” Us men folk tend to not ask directions, open the instruction manual or even look on YouTube.

We know all there is to know about everything. Ladies listen to our suggestions, do it, and discover it works. Some of the men require a switch to cut off the Juniper tree on the back of their calves.

More Than Words

I go to different schools. When I go, I pay my money to learn their way. Many years ago I returned to Bill Rogers School in rural Georgia. Bill shoots Isosceles and I prefer Weaver.

However, I tried to listen and do. Billy, the experienced Coach, kept coming up and adjusting my arm. The old Range master (God rest his soul, Ronnie Dodd) yelled at Billy: “Leave him alone. He’s hitting.” My response was for him to smack me on the side of the head as I came to learn the Rogers way.

All jesting aside, if you take nothing else from GUNS this month, whenever you go to that favorite class, heed their advice and try their methods. You might be surprised and find it works for you. If not, tuck it away in the tactical toolbox inside your brain as you might need it a later time. More simply put: Don’t be “That Guy!”

Top Gun was one of the most popular action movies of all time. Featuring a compelling story, aerial visuals that were life-changing for the era, uber-cool characters, and a pulsating musical score, Top Gun ensured that Naval Aviation recruiters could all retire early and get real jobs. Suddenly, everybody and their grandmother dreamt of strapping on an F14 and tearing across the skies.

I admit to having drunk a bit of that Kool-Aid myself. Flying an OH-58 aeroscout helicopter single pilot with the doors off is a bit like riding a 3-dimensional motorcycle. I do miss that so.

Additionally, several of our flight engineers got the avionics guys to splice boom boxes into the intercom systems of our military helicopters. I have actually flown NOE (nap of the earth) down remote Alaskan rivers at 170 knots and thirty feet while rocking to Kenny Loggins’ Danger Zone. If you were paying taxes back in the 1990s, sincerely, thanks for that.

Serving as a military aviator was such an incredible privilege. I worked hard to earn that slot, but an awful lot of it was just unvarnished luck. The physical requirements were both stringent and relentless. Sometimes, the most trivial of things would crush a young man’s dreams. Such was the case with an enthusiastic Marine Lance Corporal named Howard Foote.

The Guy

Lance Cpl. Foote was a born aviator. He served as a maintenance specialist on A6 Intruder strike aircraft and was, by all accounts, an exemplary Marine. He spent his free time flying gliders and made it clear to all who served with him that he aspired to Officer Candidate School and a career as a Marine fighter pilot. His chain of command thought that was a splendid idea and encouraged him at every opportunity.

One weekend, Foote was attempting to set a world altitude record in a civilian glider and suffered an aerial embolism. This is a potentially catastrophic variation on the bends, a condition wherein a nitrogen bubble forms in the bloodstream as a result of rapid pressure changes. Though LCPL Foote recovered, this injury disqualified him from Marine flight training. He was justifiably heartbroken.

The drive to fly high-performance aircraft can seem overwhelming. In Lance Cpt. Foote’s case, it overcame his otherwise sound judgment. Early in the morning on 4 July 1986 — Independence Day — Lance Cpl. Foote donned a flight suit, stole a crew truck, and motored out to a Marine A4 Skyhawk that was technically down for maintenance.

The ailerons were out of adjustment, and there was something amiss with the nose wheel. Regardless, Edward Foote, a young Marine who had previously only flown gliders, climbed aboard, ran through the startup procedure, and soon had the little jet turning and burning.

The Crime

It was still dark when Foote angled the nimble little attack plane onto the blacked-out runway. Before anyone was the wiser, he firewalled the throttle and blasted off into the California skies. For the time being, at least, he was free.

Lance Cpl. Foote flew the plane for about 45 minutes. He angled out over the Pacific Ocean and entertained himself doing barrel rolls and loops, covering some 50 miles in the process. Eventually, he headed back to the airfield, made five separate passes over the runway, and then executed a perfect landing. Tragically, by then, somebody had noticed that an attack jet was missing.

Foote was charged in a General Court Martial with about a zillion different infractions and confined to the brig. After some vigorous negotiations between the Marine Corps and his attorney, the charges were dropped.

In quiet moments, I suspect all involved at least quietly sympathized with the kid’s plight. Foote was credited with 4.5 months served in confinement and separated with an Other-than-Honorable discharge. His parents were reportedly thrilled with the outcome.

The Rest of the Story

Curiously, our tale does not end there. I mentioned Edward Foote was a born aviator. Once the dust settled on his little attack plane larceny, Foote found another cockpit into which to climb.

Once he properly earned his pilot ratings, he attempted to fly for both Honduras and Israel. Failing at that, he did eventually qualify as a test pilot. Foote was ultimately rated in more than twenty military and civilian aircraft and served as a contract pilot for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Before he hung up his flight suit, Edward Foote had been awarded patents in both aviation design and engineering.

Disney tells us to follow our dreams. That’s a fine sentiment if somewhat impractical. If we all aspired to be princesses or princes, there would be no one left over to do the real work in society.

It is indeed OK to chase those dreams so long as we remain at least somewhat grounded in reality. However, there are some among us, like Edward Foote, who simply seem destined to bend the world to their will. When the flight surgeon told him he’d never fly a Marine attack jet, Foote just stole one and did it anyway.

The list of reasons why he should not have done that is long. It would have been awfully easy to have balled up that airplane and killed himself and others in the process. Only he didn’t. Edward Foote went on to a successful flying career as a test pilot for NASA. In so doing, this audacious young criminal served in some strange small way as a hero to us all.

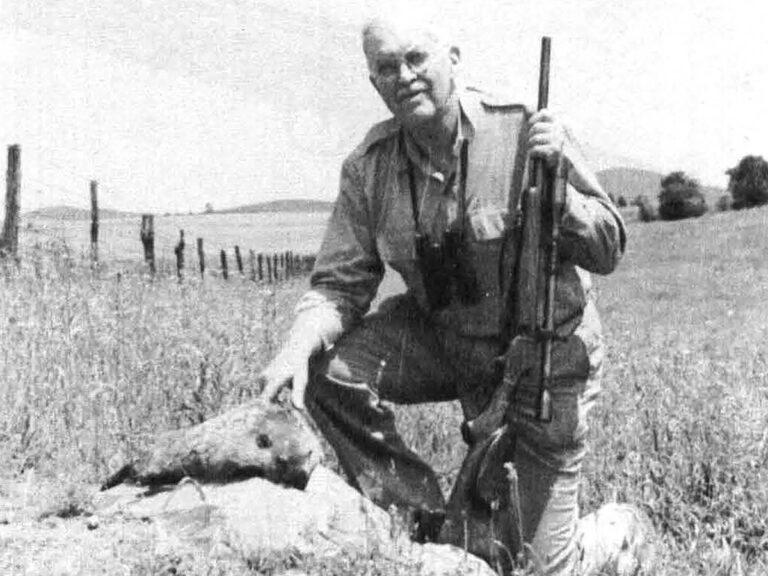

Col. Townsend Whelen’s reflections on 60 years of experience with his single-shot rifles.

The dean of firearms writers and editors, Colonel Whelen, is the author of many valuable books, notably, The Hunting Rifle and Small Arms Ballistics and Design. His latest volume, Why Not Load Your Own?, is the least expensive and most practical book on handloading available. In this article, he shares with Gun Digest readers his longtime affection for single-shot rifles.

When I was just a little shaver, there was a Winchester single-shot rifle on exhibit in a gun store in my hometown. It was for the 40–82 cartridge, had a 30-inch, half-octagon No. 3 barrel, pistol grip stock of fancy walnut, checkered, Swiss buttplate, target sights, and was nicely engraved. It was my ideal of a fine rifle, and every day after school, while it remained on view, I tramped the 2 miles downtown to admire it. In some such manner are our tastes formed, and they are likely to remain with us always.

When I was 13, my father gave me my first rifle, a Remington rolling block for the .22 rimfire cartridge. Several months later I saw an advertisement of Lyman sights, and I fitted this rifle with a set.

I think I have to thank these sights for my becoming a real rifleman, for with them on this little rifle, I soon became quite a good shot, much better than any of my boy friends, and my interest was maintained and matured, as I do not believe it would have been if I had retained the open rear sight on this rifle.

All through my boyhood years I had a lot of fun and sport with this little rifle, and I shot a lot of stuff with it—English sparrows, squirrels, chipmunks, grouse, and one woodchuck. In 1892, I was lucky enough to win a “Fourth of July” rifle match with it in the Adirondack Mountains, and that year I also shot my first buck with it.

When I was 18, I enlisted in the Pennsylvania National Guard and had no trouble in qualifying as Sharpshooter with the old 45–70 Springfield single-shot rifle, a very sterling, accurate, and reliable arm.

The following year I was shooting on my company rifle team, and I also carried this rifle through the first few months of the Spanish-American War until I won my commission.

Following that war I “discovered” the magazine Shooting and Fishing, and became much interested in the work of Reuben Harwood with 25-caliber rifles. So I purchased a Stevens No. 44 Ideal single-shot rifle for the 25-20 S.S. cartridge, but it did not seem to shoot nearly as accurately as I was sure I held and aimed it.

I know now this was due to the blackpowder factory ammunition which in small calibers never was worth a hoot for accuracy. Anyhow, still following Harwood’s writings, I obtained a Winchester single-shot rifle (low sidewall) for the 25-20 cartridge, with 26-inch, No. 2 half-octagon barrel, pistol grip and shotgun butt, and I placed a gunsling on it.

I had John Sidle bush and rechamber this rifle for the 25-21 Stevens cartridge, which was Harwood’s favorite. Sidle also fitted it with his 5-power Snap-Shot scope, which was unique in its day, as it had a much larger field of view than any other scope and was a fine hunting scope for varmints.

With this outfit I got much better results but it never entirely satisfied me in accuracy until I had Harry Pope make me a mould for his 80-grain broad base-band bullet, and furnish me with one of his lubricating pumps.

Then, with King’s Semi-Smokeless powder the rifle shot as well as I could hold it. I had a lot of fine varmint shooting with this rifle in the hills on either side of the Shenandoah Valley, and when I was ordered to California for station, it proved just the medicine for the Western ground squirrels.

For Eastern shooters I will say that these are slightly larger than the gray squirrel, with a shorter and less bushy tail. They live in colonies like prairie dogs and are a great plague to farmers. I disposed of hundreds of them with this little 25-21 rifle. Then, one day, I expressed it to a gunsmith to have some work done on it, and it was lost in transit. I have ever since mourned it.

In the meantime one season I had a chance to go deer shooting in the North Woods and I got a Winchester single-shot rifle for the 38–55 cartridge and had it fitted with a Sidle scope.

Sidle was by far our best scope maker in those days. This gun was poorly balanced and too heavy for a handy hunting rifle, but the scope did save me the embarrassment of shooting a cow in mistake for a deer.

About this time I also had a Western hunt in view and I got a similar rifle for the 45–70 cartridge, fitted only with Lyman sights. But despite carefully handloaded ammunition it was not as accurate as the old 45–70 Springfield, and I soon disposed of both these rifles.

Then, in 1900, Horace Kephart published in Shooting and Fishing his celebrated article on the use of lead bullets in high-power rifles. He had used a Winchester single-shot rifle for the 30–40 Krag cartridge, and the accuracy he obtained with both jacketed and lead alloy bullets was better than anything I had been able to achieve to that date.

So an order went in to Winchester for one of these rifles with a 30-inch Number 3 nickel-steel barrel with .308-inch groove diameter, pistol grip, shotgun butt, and sling. This rifle started a long series of experiments with various loads, methods of resting the rifle, effect of rests on accuracy and location of center of impact, temperature, cleaning, etc., the results of which I gave to riflemen from time to time in the magazine Arms and the Man.

A little ignition difficulty was experienced, so I had Niedner fit a Mann-Niedner firing pin, .075 inch in diameter, round headed, with an .055-inch protrusion, and this trouble ceased. This is an absolutely necessary alteration with all our single-shot actions, which were designed in blackpowder days.

By this time I had been shooting for several years on the Army Infantry Rifle Team, and I felt quite sure that my results were fairly free from errors of aim and hold. By this time I had also discovered the bench rest.

In 1906, I got a 2 months leave and went on a hunt in British Columbia, taking this 30–40 along as my only rifle. It performed there as well as on the range, and I got mule deer, sheep, and goat with it.

One very cold day, in a foot of snow, I came on a band of sheep close to timberline. They evidently caught a glimpse of me for they banded together, and started off, but soon slowed down and resumed feeding.

I thought I had spotted a ram in the band, and I monkeyed around them for an hour, by which time I was nearly frozen and had to quit. As I left them, it occurred to me to see if I could unload and load my rifle with my hands badly numbed with cold. I was utterly unable to do so in any reasonable time.

To my mind this is the only disadvantage of a single-shot rifle as compared with a repeater. Certainly, the experience of our older sportsmen the world over with good single-shot rifles has been that they can be fired with all the necessary rapidity under normal conditions. However, I must add one other requirement—the single-shot rifle must extract its fired cases easily. Some don’t, due usually to poor chambering or excessive loads.

On a hunt a few days later I came on an enormous rock buttress with two peaks standing up like the ears of a great horned owl. The Chilcotin Indians call this rock “Salina,” which is their name for this owl.

On a ledge on the face of the cliff was a big goat. I guess the range was about 500 yards, and I could see no way to get closer, so I lay down and took the shot, holding 2 feet above the goat’s back. Of course I missed that, and two other shots I pulled, and the goat leisurely climbed up and disappeared between the two pinnacles.

After a lot of climbing and scrambling, I found my way to the back of this rock mass where it was equally precipitous, and while working around at the base of the cliff I heard something above me, and looking upward I saw the goat or one just like it.

At the shot it loosened all holds and, in a shower of small rocks, landed close to me. Then and there I named this rifle “Salina.” I continued to use it as a testing piece for many years, and I also hunted a lot with it in Panama from 1915 to 1917. In 1911, I fitted it with a Winchester 5A scope, and thereafter all my dope was recorded in minutes of angle, from which it was easy to determine elevations, trajectory, and bullet drop.

About this time the NRA was developing interest in outdoor shooting with the smallbore rifle at 50, 100 and 200 yards. Before this scarcely anyone had shot the 22 at longer distances than 25 yards and little was known of the capabilities of the .22 Long Rifle cartridge at longer distances.

So I got another Winchester single-shot for this cartridge, with 26-inch No. 3 barrel, set triggers, and sling. I fitted it with my 5A scope and proceeded to give it a good trial at all distances up to 200 yards. I soon found that various makes of ammunition have quite different results in accuracy.

With the makes that proved best it would just about group in 2½ inches at 100 yards. This has proved to be about the best that can be expected of this rifle with this cartridge, and this limitation was what finally caused Winchester to develop their celebrated Model 52 rifle for smallbore match shooting.

Generally speaking, the old Ballard is the only American single-shot action that has given fine accuracy with the .22 Long Rifle cartridge. However, with this Winchester, I did determine the angles of elevation for all distances, which had not been known or at least never published before I published my table.

Also, before I did this shooting, it was not known that there was so much difference in the accuracy of various makes of cartridges in a certain individual rifle.

Following the loss of my old 25-21 rifle by the express company, I had to have another varmint rifle, so I procured still another Winchester single-shot for the 25-20 S. S. cartridge, and proceeded to develop smokeless powder loads for it.

I finally found that the best was the 86-grain, soft-point, jacketed bullet with a charge of du Pont Schuetzen powder that filled the case to the base of the bullet. This load shot like nobody’s business, and it gave the finest accuracy up to 200 yards that I had obtained up to that time or heard of anyone else obtaining except with Pope muzzle-breechloading rifles. But my elation was short-lived, for the barrel began to pit, and in less than 500 rounds it was ruined.

About this time we had been devoting much study to the cleaning of rifles. It seemed to us that stronger ammonia was the only satisfactory cleaning solution, so I had a new barrel fitted to this rifle and cleaned it immediately after firing with this ammonia.

This did not do a particle of good, and again the barrel was ruined in 500 rounds. The same thing occurred with a Winchester Model 92 rifle for the 25-20 W.C.F. smokeless cartridge of Winchester make. When I wrote them a letter of complaint, they stated that I should not blame the rifle for what was evidently the fault of the powder (which they used)!

However, I excuse them for no one knew much about such things in those days. Of course we now know that the old potassium chlorate primer was the devil in the woodshed. With that primer, in small bores like .25 caliber the relatively small charge of powder did not dilute the primer fouling as it did in larger bores like the .30 caliber, and the primer got in its hellish work at once and fast.

For a while there seemed to be no solution for this problem of smokeless powder in small bores. Then, Winchester came out with stainless steel barrels made to order, so I had them build me still another rifle with this barrel, and modeled almost exactly like the fine old 25-21 that I had lost, only it was chambered for the 25-20 W.C.F. repeater cartridge, because I had an idea that the single-shot cartridge would soon be obsolete, which it was.

Clyde Baker stocked this rifle, and fitted it with a finger lever that hugged the pistol grip. But before I had time to do much with it, the Kleanbore primer was developed, and this solved all our cleaning and rusting problems.

Also at this time the development of the .22 Hornet cartridge shifted our work from the older cartridges to the modern high-intensity types. Later, however, I found that I could obtain splendid results with my 25-20 W.C.F. rifle with a load consisting of the 87-grain, soft point, spitzer bullet made for the 250–3000 Savage cartridge, bullet seated far enough out of the case to touch the lands, and a charge of 11 grains of du Pont No. 4227 powder.

The trajectory seems to indicate that the velocity is about 2,000 fps.; evidently, a fine wild turkey load. Of course, the overall length of the load is too great for 25-20 repeater rifles.

Up to this time you will note that I had been using Winchester actions exclusively on all my single shots, both because of their strength and durability, and because they were the only new actions that could be procured at that time.

After working for some years with the .22 Hornet cartridge in bolt-action rifles, a friend gave me a good Sharps-Borchardt action, so I had Frank Hyde obtain a 22-caliber Remington high-pressure steel barrel with a 15-inch twist, and fit it to this action and chamber it for the 22–3000 Lovell R2 cartridge.

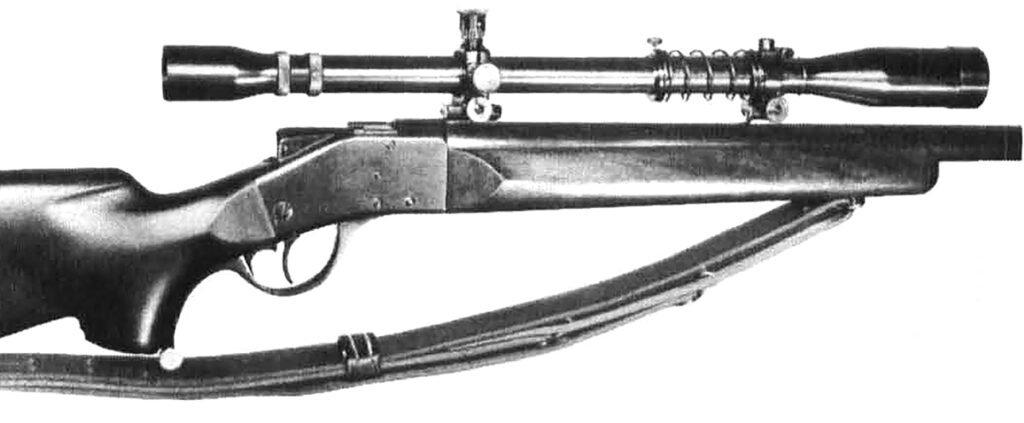

Frank also worked over the firing pin, and made the pin retract with the first down movement of the lever, two very necessary alterations with this action. This rifle, fitted with a 10X Unertl Varmint scope, is a fine, accurate varmint rifle. With good 50-grain bullets and 15.5 grains of 4227 powder it will group reliably, day after day, in about a minute of angle, which is the best that can be expected from this cartridge and a single-shot action.

Occasionally, a five-shot group as small as half an inch turns up at 100 yards, but such is a lucky group. This rifle, however, has one peculiarity. Almost invariably the first shot fired from a clean, cold bore strikes from half an inch to an inch above the succeeding group at 100 yards.

I think this is because the groove diameter of the barrel is 0.2235 inch, while all the bullets I have used so far have measured .224. This is no drawback because, knowing it I can allow for it, or can fire a fouling shot before starting on the day’s hunt.

It has quite generally been proven that with equal barrels and loads, a single-shot action will not give as fine accuracy as a modern bolt action.

There are apparently only two exceptions, the Ballard action for the .22 Long Rifle cartridge, and the Hauck single-shot action, which is a horse of a different color with its better bedding, ignition, and breeching up.

I do not mean to imply that there have not been any single-shot rifles that would give gilt-edge accuracy. There have been quite a few, but I would think that any custom riflemaker who guaranteed to produce a single-shot rifle that would average groups under a minute would soon go broke.

So far as we have been able to determine, the difficulties with the single-shot action seem to be in the two-piece stock, the breeching up and the ignition. The single-shot rifle also seems to have a greater jump and barrel vibration than the bolt action.

The difference in elevation required between full charges and reduced loads is much greater with it. In this connection it has long been my experience that to get the best accuracy from a single-shot rifle the forearm should not touch the receiver. It should be possible to pass a thin sheet of paper between the two.

The most accurate single-shot rifle that I have owned is one for the 219 Improved Zipper cartridge. I traded Bill Humphrey out of a fine Winchester rifle with 26-inch, No. 3 Diller barrel, .224-inch groove diameter and 16-inch twist, double set triggers, and a fine stock made by him.

I had this chambered for the Improved Zipper cartridge with a very perfect reamer made by Red Elliott. This cartridge is simply the 219 Winchester Zipper case fireformed to a 30-degree shoulder angle. You simply fire the factory cartridge in the rifle and it comes out improved.

The best load I have found for this rifle has been 32 grains of du Pont No. 3031 powder with the 50-grain Sierra bullet. M.V. is probably around 3,900 fps. After working up this load and sighting in, it gave three five-shot groups at 100 yards measuring .65, .80 and .80 inch.

For 3 years, I have used this rifle almost exclusively for all my chuck shooting. Its accuracy and very flat trajectory have given a high percentage of hits at long ranges. With it I made the longest first-shot hit I have ever pulled off on a chuck; difficult to pace because it was up and down hill over rough ground, but it was certainly considerably in excess of 300 yards.

The Stevens No. 44½ action is another on which a most excellent and accurate rifle can be built, particularly for cartridges not to exceed the 219 Donaldson in power. My old friend Jim Garland, who has been my companion on many chuck hunts over the past fifteen years, has a glorious piece built on this action.

The Diller barrel was chambered and fitted for the R2 Lovell cartridge, and the lock work done by C. C. Johnson. Bill Humphrey made the stock and the scope is a superb 6X Bear Cub Double. With each lot of cartridges that Jim loads for it, usually with 15.5 grains of 4227 powder, he tests it on the bench, and it has never failed to average under an inch, and with some lots of bullets it gives around ¾ inch.

He regards it as his best varmint rifle, and its bag numbers in excess of 300 chucks and hawks. I remember one afternoon 2 years ago when we were separated by a range of hills. Every 2 or 3 minutes I would hear Jim shoot, and toward sundown I wandered over to see what in thunder he had been shooting at.

He had a stand on a hill above a creek bottom that was honeycombed with holes, and toward dusk the chucks began to come out. When we went down, we picked up 36 of them shot at distances from 150 to 250 yards. Both Jim and I are rather of the opinion that a first-rate riflemaker will turn out a larger proportion of gilt-edge shooting rifles when he uses the Stevens 44½ action than with any other.

Jim also has a superb engraved Ballard for the 25 Rimfire cartridge, the work of Niedner, Shelhammer and Kornbrath. With Remington or Peters cartridges, it groups the first 10 shots at 50 yards in about ¾ inch, and the second 10 when it is warmed up a little, in about half an inch, and is his favorite squirrel rifle.

My latest venture in the realm of single shots has been one of the most interesting. Three years ago I took Salina, my old 30–40 Winchester Single Shot, out of the box where it had been in store for several years, well covered in and out with Rig [Editor’s note: Rig is wonderfully effective gun grease, which I have used since childhood], with the intention of trying some new bullets in it.

To my consternation, when I put a patch through the bore it came out with red rust and many bodies of big, black ants. Ants had nested in the bore and their acid had ruined it. One day last year, looking at the old piece that had served me so well for half a century, I decided it was entitled to have something done to rejuvenate it. I had on hand a fine 25-caliber Douglas barrel, .257-inch groove diameter and 13-inch twist.

So I had H. L. Culver, my metal gunsmith, fit this barrel to the action, and I asked him to chamber it for the Krag case necked down to .25 caliber with a 30-degree shoulder angle. As it turned out, this case is very similar in shape and capacity to the 25 Donaldson Ace. We called it the 25 Culver-Krag.

Then, Bill Humphrey made a beautiful new stock and forearm to my exact dimensions, and Mark Stith fitted one of his 4X Bear Cub Double scopes, and I had just about the finest appearing, best balanced and fitting, and steadiest holding rifle I have ever had in my hands.

The intention had been to produce an all-around hunting rifle rather than one for varmint or target shooting, and it has turned out to be just that. I have only worked up one load for it so far—the 100-grain Sierra soft point spitzer bullet and 40 grains of 4350 powder. After sighting in I fired five, five-shot groups with it at 100 yards, measuring 1.75, 1.12, .88, 1.85 and 1.98 inches.

Before you criticize these groups, consider that they were fired with a rather light-barreled single-shot rifle aimed with a low-power scope having a flat top post reticle, and that the charge was quite a powerful one. It is much more difficult to get a fine grouping with a heavy load than with a light one.

Last summer and fall I carried Salina in her new garb for probably a total of 350 miles afoot in my wanderings over the mountains adjacent to my summer home,occasionally gathering in a chuck, crow, hawk or porcupine, and always hoping for a bear or bobcat which never materialized. I have never carried a rifle that seemed as friendly.

All this pernicious activity with single-shot rifles, covering a period of 60 years, started with that rifle in the gun store window when I was a little boy, and that is the way with most of our preference for single shots.

It is not their superiority that causes us to select and work with them, but rather some romantic or historic association. An urge to acquire and experiment, not always wise, but usually one that gives deep satisfaction.

It seems to many of us that the highly efficient bolt action is but a remodeled musket in a way, that the lever action is a product of America’s unrivaled quantity-production industry, but that the single shot constructed on fine and beautiful lines by a master riflemaker is a gentleman’s piece.

Editor’s note: This article appeared in the 1953 7th Edition of Gun Digest, and, keenly aware that we tread on sacred ground, we have only lightly edited it.

Clever!

Adolf Hitler. Amidst humanity’s literally countless certifiable homicidal maniacs, Hitler consistently ranks number 1 on the psycho hit parade.

Accusing political figures of being Hitler appears to be a prerequisite for graduation from Leftist school. It has been done so many times that the sobriquet has lost a great deal of its luster. That’s because nobody is as bad as Hitler. To insinuate otherwise illuminates one’s simply breathtaking ignorance.

Donald Trump is a perennial target. Everyone from cerulean-haired militant feminists to unhinged Left-wing politicians has availed themselves of this handy comparison. A partial list of Democrats who have likened Trump to Hitler includes Kamala Harris, Bill Maher, Louis C.K., Sarah Silverman, and Jerry Nadler.

Donald Trump might not be a terribly nice man, but he has a long way to go to actually give Hitler a run for his money. Anyone who watches the news can catalog the President’s many hijinks. By contrast, Adolf Hitler institutionally slaughtered six million Jews, murdered 27 million Soviet citizens, and enslaved most of Europe. Hitler had his enemies impaled on meat hooks or slowly strangled with piano wire. Trump, by contrast, slams out mean tweets at odd hours and deports illegal immigrants. News flash–those things are not the same.

It’s All Relative

All thinking folk appreciate that Adolf Hitler really was history’s alpha villain. We’ve had no shortage of psychopaths. Jeffrey Dahmer kidnapped, killed, cooked, and ate seventeen young men and boys, but he clearly lacked vision. What made Hitler unique was that he had some proper ambition. Hitler used the apparatus of the state to take institutional murder to new, rarefied heights. Chairman Mao killed en masse because he was stupid. Stalin murdered because he was diagnosably paranoid. Hitler, however, wiped out entire people groups because he made a cold, calculating decision that his world would be better off without them.

That all begs the timeless question—if you had the means to go back in time to an era before Hitler had come to power, would you let him walk, or would you exterminate him for the good of humanity? As time machines are not real, that conundrum will remain tragically hypothetical. However, no less a source than the monster himself did claim that one man had that chance and indeed let him live. That man, a British infantry private named Henry Tandey, was quite the hero in his own right.

The Guy

Henry James Tandey was born in August 1891 in the Angel Hotel on Regent Street in Leamington, Warwickshire, in the UK. Henry’s Dad was a former soldier. His Mom died when he was young. That happened a lot back then.

Young Henry languished for a time in an orphanage and eventually took a job as a boiler attendant in a hotel. In the summer of 1910, he enlisted in the Green Howards, a line infantry regiment in the King’s Division. This took him to Guernsey and South Africa. However, in 1914, things got real. Tandey’s first taste of serious action was at Ypres.

Nowadays, American troops serve a set period in a war zone and then rotate home. Not so back during World War 1. These poor slobs fought until they were killed, were too badly wounded to fight any more, or the war ended. Henry Tandey was in the thick of it at places like the Somme, Passchendaele, and Cambrai. He fought from the opening salvoes of the war to the very bitter end.

Courage Rewarded

Henry Tandey’s courage under fire bordered upon the superhuman. This was the citation for his Distinguished Conduct Medal—

“He was in charge of a reserve bombing party in action, and finding the advance temporarily held up, he called on two other men of his party, and working across the open in rear of the enemy, he rushed a post, returning with twenty prisoners, having killed several of the enemy. He was an example of daring courage throughout the whole of the operations.”

Next Level Awesome

Henry Tandey never gained much rank. On 28 September 1818, he was still a private at age 27 after nearly four years in combat. However, it was on this day that Tandey earned the Victoria Cross, his nation’s highest award for valor. This was the citation—

“For most conspicuous bravery and initiative during the capture of the village and the crossings at Marcoing, and the subsequent counter-attack on 28 September, 1918. When, during the advance on Marcoing, his platoon was held up by machine-gun fire, he at once crawled forward, located the machine gun, and, with a Lewis gun team, knocked it out. On arrival at the crossings, he restored the plank bridge under a hail of bullets, thus enabling the first crossing to be made at this vital spot.

“Later in the evening, during an attack, he, with eight comrades, was surrounded by an overwhelming number of Germans, and though the position was apparently hopeless, he led a bayonet charge through them, fighting so fiercely that 37 of the enemy were driven into the hands of the remainder of his company. Although twice wounded, he refused to leave till the fight was won.”

Meeting the Monster

At the same time that Henry Tandey was slogging through the trenches earning his nation’s most esteemed awards for gallantry, a certain nondescript Austrian corporal was enduring comparable deprivations on the other side of no-man’s land.

Adolf Hitler was 25 when WW1 kicked off. He volunteered for service with the Bavarian Army at the onset of hostilities. His Austrian citizenship should have disqualified him. However, he was allowed to remain in uniform due to a clerical error.

Hitler fought in many of the same battles as did Tandey. He served as a dispatch runner on the Western Front in France and Belgium. In the days before reliable radio, critical messages were often conveyed across the battlefield by individual messengers. This was a hazardous job that produced an inordinate number of casualties. By all accounts, Hitler served admirably in this role, earning the Iron Cross Second Class for valor.

On the day he earned his Victoria Cross, Henry Tandey was fighting with the 5th Duke of Wellington’s Regiment at the French village of Marcoing. As the battle was finding its level and the violence was dying down, Tandey encountered a wounded German soldier who wandered into his line of fire.

For reasons lost to history, he chose not to kill this man. There were credible allegations that this wounded straggler was none other than Corporal Adolf Hitler. Here’s where the story gets weird.

There are lots of reasons to believe this was not the case. Records were spotty. Hitler might have even been home on leave on this particular date. Nobody is completely sure. However, Hitler himself had some strong opinions on the subject.

The Painting

Henry Tandey ended the war a true hero. In 1923, the Green Howards Regiment commissioned a painting of Tandey carrying a wounded man at the Kruiseke Crossroads northwest of Menin in 1914. This painting was crafted from a sketch made at the time of the event. A building depicted behind Tandey was owned by the Van Den Broucke family. The regiment gifted this family with a copy of the painting.

A member of Hitler’s staff named Dr. Otto Schwend ended up with a copy as well. I couldn’t determine if this was a second copy or the one gifted to the Ven Den Broucke family.

The Nazis stole a lot of stuff. Schwend had served as a medical officer during the Battle of Ypres in 1914. Knowing Hitler’s affection for mementos of his wartime service, Schwend had a large photograph made of the painting and presented it to der Führer as a gift. Upon detailed study, Hitler identified Tandey as the man in the painting who had spared his life on the battlefield in 1918.

The Prime Minister

In 1938, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain famously visited Hitler at the Berghof. These talks ultimately led to the Munich Agreement that spawned Chamberlain’s infamous “Peace in Our Time” announcement.

While together, Chamberlain and Hitler discussed the painting, the photograph of which Hitler had prominently displayed. Hitler told the English PM, “That man came so near to killing me that I thought I should never see Germany again; Providence saved me from such devilishly accurate fire as those English boys were aiming at us.”

Hitler subsequently asked Chamberlain to track down Tandey and give him his warmest regards. Though the details are disputed, Chamberlain purportedly did call Tandey’s home upon his return, speaking with a nine-year-old relative named William Whateley. At the time, Tandey worked for the Triumph Motor Company. As near as I could tell, Chamberlain and Tandey didn’t actually speak.

The Rest of the Story

Tandey remained in the Army after the war, refusing promotions so he could continue to serve as a private. In this capacity, he deployed to Turkey and Egypt. He was finally mustered out in 1926.

Tandey married upon his return home, but never had kids. In 1940, while living in Coventry, his home was bombed by the Luftwaffe. Tandey reportedly rescued several victims from their burning homes during the Blitz.

When approached by a journalist at the time, he was once asked about the story concerning his sparing the life of Hitler. He said, “If only I had known what he would turn out to be…when I saw all the people and women and children he had killed and wounded I was sorry to God I let him go.”

Tandey worked for Triumph for a total of 38 years. He died in 1977 at the ripe age of 86 and was cremated. His ashes were interred among his brothers at the Masnieres British Cemetery at Marcoing, France, where he had earned his Victoria Cross. It was an honorable end for the man who quite likely spared Hitler.

“His appearance is striking. Tall, straight as an arrow, dark-complexioned, carries himself with ease and grace, gentlemanly and courteous in manner, never betraying by word or action the history of his eventful life.”

— Kinsley Graphic, December 14, 1878.

Robert Andrew “Clay” Allison was once asked what he did for a living, and he replied, “I am a shootist.” It is simply impossible to verify the multiple accounts of his numerous outrageous activities, with “news” being what it was at the time and a century intervening. Though many of the tales were highly exaggerated, if even half were true, people were right to be afraid of him.

Born with a clubfoot, Robert Clay Allison, known as “Clay,” was born September 2, 1840, in Waynesboro, Tennessee, to Jeremiah and Mariah Brown Allison. His father, a Presbyterian minister, also worked in the cattle and sheep business and died when Clay was only five. Clay was said to have been restless from birth, and as he grew into manhood, he became feared for his wild mood swings and easy anger.

Clay Allison

Clay worked on the family farm until the age of 21 when the Civil War broke out, and he immediately signed up to fight for the Confederacy, enlisting in the Tennessee Light Artillery division on October 15, 1861.

His clubfoot did not seem to hamper his ability to perform active duty. In fact, he was eager to fight, sometimes threatening to kill his superiors because they would not pursue Union troops when they were running away from the battle.

However, just a few months later, on January 15, 1862, he received a medical discharge from the service. His discharge papers described the nameless illness as: “Emotional or physical excitement produces paroxysmal of a mixed character, partly epileptic and partly maniacal.”

The discharge documents further suggested that the condition might have resulted from “a blow received many years ago, producing a depression of the skull.” That head injury has been the usual explanation for Allison’s psychotic behavior when drinking, perhaps explaining some of his later violent activities.

But, on September 22, 1862, Clay reenlisted in the 9th Tennessee Cavalry and remained with them until the war’s end. He suffered no further medical complications and became a scout and a spy for General Nathan Bedford Forrest.

He began sporting the Vandyke beard he wore the rest of his life in imitation of the flamboyant cavalry commander. On May 4, 1865, Allison surrendered with his company at Gainesville, Alabama. He was held as a prisoner of war until May 10, 1865, having been convicted of spying and sentenced to be shot. But the night before he was to face the firing squad, he killed the guard and escaped.

Upon his return to civilian life, Allison became a member of the local Ku Klux Klan, whose dislike for the Freedmen’s Bureau of Wayne County nearly led to armed conflict. Allison was involved in several confrontations before he left Tennessee for Texas. It was said that when a corporal with the Union Third Illinois Cavalry arrived at the family farm, intending to seize the contents of the property, Clay retrieved his gun from the closet and calmly killed the Union soldier.

Settling down for a while, Clay learned the ways of ranching and became an excellent cowhand in Texas. He signed on with Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving in 1866 and accompanied them on their famous Goodnight-Loving Trail through Texas, New Mexico, and Colorado. Around 1867, Clay worked as a trail boss for M.L. Dalton. He then worked for his brother-in-law, Lewis Coleman, and Irwin W. Lacy, two cattle ranchers who were also legends in their own time.

While in Texas, Allison was said to have had an altercation over the rights of a water hole with a neighbor named Johnson. The two settled the matter by digging a grave and entering the pit with bowie knives. The loser would be buried in the pit, and the winner would gain the rights to the waterhole. Allison had excellent skills with a bowie knife and didn’t lose, but whether or not he killed his neighbor is unknown.

In 1870, Coleman and Lacy moved to a spread in Colfax County, New Mexico. The Allison brothers accompanied them and, as payment for their work driving the herd, they received 300 head of cattle. Clay took his share and homesteaded a ranch at the junction of the Vermejo and Canadian Rivers, nine miles north of present-day Springer. The two rivers ensured ample water, and Allison built his ranch into a profitable business.

The Allison brothers quickly entered the “social scene in Cimarron and Elizabethtown, and within only a few weeks, the cowboys and ranchers were calling Clay a friend. But the law had not yet come to these early settlements, and the cowboys‘‘ Saturday night visits to town would find them drinking hard, pulling out their six-shooters, and riding up and down the streets yelling and shooting. They made their rounds to the local saloons and gambling halls, where they shot out lamps, lanterns, mirrors, and glasses and were said to have particularly enjoyed making newcomers “dance” as shots were fired at their feet.

In the fall of 1870, Clay Allison showed the citizens of Elizabethtown how mean and violent his temper was. Charles Kennedy, who was suspected of killing and robbing overnight guests in his isolated cabin on Palo Fletchado Pass, was being held at the Elizabethtown jail. Clay, along with several others, broke into the jail, threw a rope around his neck, and dragged him by a horse up and down Main Street until long after he was dead. Allison then decapitated Kennedy, carrying his head in a sack twenty-nine miles to Cimarron, and demanded that it be staked on a fence at the front of Lambert’s Inn (later the St. James Hotel.)

On April 30, 1871, Allison and two others were said to have stolen 12 government mules belonging to the Fort Union Commander, General Gordon Granger. In the fall, he tried the same stunt again, but when military men came running to the corral, Allison accidentally shot himself in the foot during the confusion. The would-be rustlers escaped to a hideout along the Red River, where Allison sent his friend Davy Crockett (a nephew of the American frontiersman) to fetch Dr. Longwell from Cimarron. Though Clay was treated, he spent the rest of his life with a permanent limp.

After recuperating, Clay was on a drinking spree in a local saloon when suddenly he took a dislike to a man named Wilson. Wilson had the good sense to depart quickly but left Clay in a foul mood. Clay then happened into the County Clerk’s office, where he took offense to something that John Lee, the county clerk, said and slung a knife at him, stapling his sleeve to the timber of a door. Lee broke free and ran across the street to Dr. Longwell’s office.

Next, Clay repeated his knife act with a young lawyer, Melvin W. Mills, who also fled to the doctor’s office. Mills described what had happened to the doctor and took up his gun, stating that he would have to kill Allison in self-defense. While the doctor was trying to persuade the lawyer away from such a dangerous act, he noticed that Allison was riding toward the office, at which time the clerk and lawyer promptly fled out of the back door.

The doctor exited his office to meet Allison, telling Clay he had been acting badly. The rancher only laughed, stating that he had nothing against Mills or Lee but wanted Wilson’s ear, then rode off in a vain search for Wilson. Mills would carry a grudge against Allison for years, which was later evidenced in the Colfax County War.

Having no fear when it came to other men, Clay was always shy and uncertain when it came to women. But that changed when he met a considerably younger Dora McCullough. When Clay and his brother, John, met Dora and her younger sister, both were smitten. The girls, who were born and raised in Sedalia, Missouri, were orphaned during the Civil War and lived with their guardians, Mr. and Mrs. A.J. Young, on what is now known as the Vermejo Ranch.

Mrs. Young liked John, but Clay’s reputation had preceded him, and she looked upon him with disapproval. Not to be deterred, the two couples eloped in 1873 and, upon their return, begged the forgiveness and blessing of the Young’s. Over time, the Youngs forgave Allison when they observed that Clay never went looking for trouble but didn’t shirk it when it came his way.

After his marriage, Allison met the only man who was able to out-draw him, Mace Bowman. Meeting in Lambert’s Inn one evening, talk turned to Wild Bill Hickok’s fast draw, and Allison stated that he thought he was even faster. Bowman begged to differ and wagered a gallon of whiskey that he could outdraw Allison. In the center of the room, they paced off the distance to the wall and turned. Before Allison was able to get his gun out of the holster, Mace’s six-shooter was pointed at his chest. Allison was amazed and paid Bowman the gallon he owed him. The two took the whiskey to the country, where Bowman taught Allison his lightning-rapid trick.

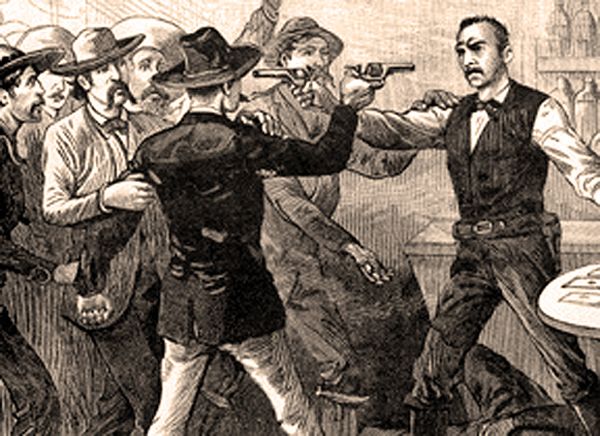

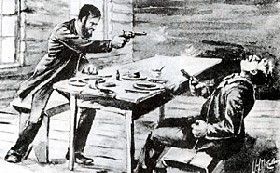

Allison shoots Colbert

On January 7, 1874, Clay killed gunman Chunk Colbert, a known gunslinger. Colbert came to the area looking for a fight with Allison. Some say that Colbert fancied that he could outdraw and outshoot anyone, including Allison. Others say that he wanted revenge for his uncle, Zachary Colbert, the ferryman that Allison had pummeled at the Brazos River nine years earlier. Reportedly, Colbert had already killed six men in Texas and bragged that Allison would be his seventh. Not giving away his motives, Colbert found Allison, and the two spent most of the day together drinking and gambling on horse races.

That night, Colbert invited Allison to dinner at the Clifton House, and Allison accepted. Guessing that there might be trouble, Clay was very cautious, but the talk was friendly as they enjoyed a large meal spread out before them. When they were seated it Colbert laid his gun in his lap, and Allison laid his gun on the table. After the meal was finished, Colbert suddenly reached for his gun under the table and leveled it towards Allison.

The perceptive Allison followed suit, and when Colbert’s gun nicked the table, the shot was deflected, and Allison shot him in the head. Later, Allison was asked why He had agreed to have a meal with him and answered, “Because I didn’t want to send a man to hell on an empty stomach.” Colbert was buried in an unmarked grave behind the Clifton House.

Charles Cooper, a friend of the late Mr. Colbert, witnessed the shooting. Less than two weeks after Colbert’s death, Cooper was seen riding with Allison on January 19, 1874. He was never seen again. People started talking, thinking that Allison had killed him, but others thought that Clay simply intimidated the man into leaving.

No evidence was ever found to prove the suspicions that Clay had killed the man, but this event would come back to haunt him during the Colfax War.

In the next few years, Clay’s reputation expanded at the same pace as the booming town of Cimarron. The new owners of the Maxwell Land Grant were aggressively exploiting the resources of the grant and were busy with their attempts at evicting the squatters, settlers, farmers, and small ranchers living on the land.

The power behind the grant was a group of politicians and financiers called the “Santa Fe Ring.” Melvin W. Mills, the lawyer that Allison had thrown a knife at several years before, and Dr. Longwell, who had treated Clay’s bullet wound, jumped on the bandwagon and joined the political forces behind the “Ring.” In a bitter 1875 election, Dr. Longwell was made probate judge, while attorney Mills was made a state Legislator.

As the burgeoning Cimarron settlement was trying to adjust itself to the influx of prospectors, gamblers, and politics, it found itself in the midst of a great conflict between the land grant company and the settlers of the area. Sheriffs served eviction notices, and retaliation began. Grant pastures were set on fire, cattle rustling increased, and officials were threatened at gunpoint. Grant gang members made nighttime raids of area homes and ranches with threats of violence. The mightily opposed residents formed their own organization, which they called the Colfax County Ring, which some said was led by Clay Allison.

During this time when Cimarron was in need of salvation, Reverend Franklin J. Tolby enlisted with the Methodist Circuit Riders, delivering his sermons in Cimarron, Elizabethtown, Ute Park, Ponil, and Sugarite.

Having always had respect for men of the cloth, Clay Allison was one of the first to welcome the minister. Tolby loved Cimarron, planning on making it his home, and quickly sided with the settlers in their opposition against the land grant men.

He was very open about his opposition, saying that he would do everything that he could to stop the land grant owners. On September 14, 1875, the 33-year-old minister was found shot in the back in Cimarron Canyon, midway between Elizabethtown and Cimarron, near Clear Creek.

Rumors began to circulate that the new Cimarron Constable, Cruz Vega, was involved in the murder of the Methodist circuit rider. Tolby’s fellow minister and friend, Reverend Oscar Patrick McMains, took up the fight against the “grant men” after Tolby’s murder.

Despite a $3,000 reward for the murderer, no progress was being made on finding Tolby’s killer, and McMains was becoming impatient. The pastor turned to Allison for help, who was more than ready to play judge on horseback.

On the evening of October 30, 1875, a masked mob, who was said to have been led by Clay Allison and Minister McMains, confronted Vega. The constable denied having anything to do with the murder, blaming it on a man by the name of Manuel Cardenas, who had been hired by his uncle, Francisco Griego, and mail contractor Florencio Donaghue.

Obviously, the mob did not believe him, and he was pummeled and hanged by the neck of a telegraph pole. Unable to stomach the violence, the Reverend McMains panicked and fled midway through the session.

After finding Vega’s body later Sunday morning, Francisco “Pancho” Griego, Vega’s uncle, claimed the corpse. On Monday morning, he and a friend transported the boxed remains to the Cimarron cemetery. Suddenly, Clay rode up with his cowboys and informed Griego that Vega was not to be buried in the same cemetery as his victim, Tolby.

Angry but helpless, Griego, along with several mourners, left and began preparing for burial outside the graveyard. Following them, Allison further instructed that Vega was not to be buried inside the city limits. Finally, the remains were placed about a half-mile west of the St. James Hotel.

Later that same day, November 1, 1875, Francisco “Pancho” Griego, along with Cruz’s 18-year-old son and Griego’s partner Florencio Donahue, began making threats to the townspeople in response to Vega’s death. Looking for trouble, they wandered into the St. James Hotel.

Allison was in the saloon when Griego accused him of being involved in the hanging of Vega. Griego began fanning himself with his hat in an attempt to distract Allison while he drew his gun. But Allison was not fooled and fired two bullets, killing Griego instantly.

The saloon was closed until an inquiry could be held the next morning, and according to local accounts of the day, the saloon closing was the most unfortunate aspect of the whole incident. Allison and his men ran rough-shod over Cimarron all week, spreading general chaos. On Thursday, they were said to have paraded into the local newspaper, brandishing a knife at the editor, and on Friday night, took over Lambert’s Inn, where Allison was said to have stripped naked and performed a war dance over the spot where he had shot Griego, wearing a red ribbon tied around his private parts. On November 10, Allison faced the charges in the killing of Griego, but the charges were dropped when the court ruled the shooting a justifiable homicide.

In the meantime, Manuel Cardenas, the man whom Vega had implicated prior to his death, was arrested and questioned in Elizabethtown. He claimed that Vega had shot the minister, adding that Santa Fe Ringers Mills and Longwell were also behind the killing. When word of this got out, Mills barely escaped a furious lynch mob in Cimarron as he alighted from a coach. Longwell fled in a buggy to Fort Union and safety just ahead of pursuers Clay and his brother John.

However, during his protracted hearing, Cardenas retracted his earlier accusations against Mills and Longwell, stating that he had been coerced at gunpoint, at which time Mills and Longwell were cleared. However, the vigilantes obviously didn’t believe his testimony, and when Cardenas was escorted back to the jail, he was shot to death.

Believing that Allison was the head of the vigilantes, this last shooting so enraged the Mexican population of Cimarron that they were determined to have Clay’s scalp. Armed Mexican bands roamed the street, and the atmosphere was so charged that Sheriff Orson K. Chittenden and Deputy Burleson hid Clay for a time at the Chittenden ranch, 20 miles south of Springer. When Allison again began to go about Cimarron, he was said to be a walking arsenal, accompanied by 45 cowboys.

The truth about Tolby’s murder later suggested that the parson, unfortunately, witnessed Griego shooting a man in an argument. When the man later died, Tolby planned to seek an indictment against Griego, who set up Tolby’s murder to silence him. The Santa Fe Ring was dragged into it after Cardenas was “questioned” at gunpoint in Elizabethtown by Joseph Herberger.

Evidently, Herberger had been promised a political position by Ringmen Mills and Longwell during the earlier elections earlier in 1875. When the two had failed to follow through, Herberger reportedly forced Cardenas to implicate them. Cardenas later retracted his statement about the Ring men. It was never known who killed Cardenas.

Between the Ring men, the anti-grant vigilantes, and the Mexicans, who had solicited the support of the native Indians, Cimarron was out of control. The Reverend McMains was busy enlisting additional aid from the settlers, telling them that the anger of the Mexicans and Indians was the work of the Grant men, urging them to place themselves at the disposal of Allison.

Eventually, guards were posted at all entrances to Cimarron, and no one was allowed to leave town without Allison’s permission. On November 9, 1875, the Santa Fe New Mexican informed the public that Cimarron was in the hands of a mob. Cimarron was actually in the midst of the Colfax County War, which took approximately 200 lives.

Heaping more fuel on the fire, Governor Samuel Beech Axtell, a Santa Fe Ring tool, signed a document on January 14, 1876, that attached Colfax to Taos County. He claimed the change would mean improved law and order. The citizens reacted in fury over the bill, correctly surmising the interference of the Santa Fe Ring.

At about 11 p.m. on January 19, 1876, Allison and two other men, reacting to a scathing editorial where the paper had pointed a finger at Clay Allison as a leader catering to mob violence, broke into the News and Press office and set off a charge of black powder. Then they threw the press into the Cimarron River. Later, he returned to the newspaper office and paid $200 for damages.

Governor Axtell, bothered by Allison’s antics and spurred on by the attorney Mills, was quoted as saying that he “intended to have Allison indicted and punished, or compelled to leave the county.” On February 21, 1876, the governor gave life to a dormant Allison warrant by issuing a $500 reward for Clay, “who is guilty of the crime of murder in killing Charles Cooper,” Chunk Colbert’s friend who had disappeared back in January 1874.

In May or June 1876, as Governor Axtell passed through Cimarron in a stagecoach, Allison climbed aboard and rode with him to Trinidad, Colorado. Clay asked what kind of man it was who had so interfered with his personal freedom.

Axtell countered by asking why Allison did not surrender himself on bail and faced his judgment like a man. Clay replied that he had no objection if he could get a fair trial but that he would “never submit to a real trial in Taos County by greasers.” The governor responded that he would demand a fair trial for Allison. Later, Allison turned himself in.

Represented by Charles Springer, the trial was held in Taos. Springer’s main defense was that a body had never been found, and everyone was simply guessing Cooper had been murdered because he had not been seen. Allison was acquitted, and Axtell, true to his promise, declared him a free man.

Clay’s most loyal companion was his brother John, and on December 21, 1876, having just come off the trail, the two decided to have some fun in Las Animas, Colorado. Spotting a local social going on, the two drunk cowboys crashed the party, dancing with some very unwilling partners.

Charles Faber, the deputy sheriff and town marshal, asked the Allison brothers to remove their weapons, but his request went unheard. Faber then left, deputized two local men, and, with a shotgun in hand, led them back into the social.

As they came through the door, someone shouted: “Look out!” When John reached for his gun, Faber shot him. Standing at the bar, Clay spun around and fired four shots at Faber, one proving to be fatal. John had already been shot in the chest and arm and was shot yet again in the leg as Faber’s shotgun discharged when he fell. The two deputized men ran from the dance hall, Allison behind them in pursuit, but lucky for them, they escaped.

Clay ran back into the dance hall, calling for a doctor, and slid over to his brother, bringing Faber’s body with him. To John, he said, “Look here! John, this is the s.o.b. that shot you. Everything’s going to be all right. You will be well soon!” Both Clay and John were arrested and charged with manslaughter, but the charges were later dismissed on grounds of self-defense. John recovered from his wounds.

Finally, the restless Clay moved on. On March 3, 1877, he sold his ranch, land, and stock to his brother John for $700. He spent a brief period of time in Sedalia, Missouri, but finally established himself in Hays City, Kansas as a cattle broker.

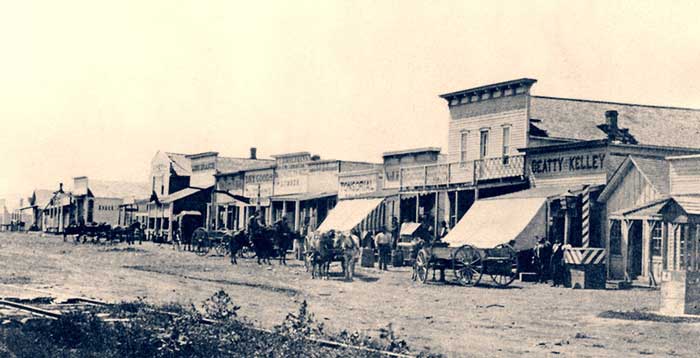

The numerous stories of Clay Allison’s exploits made him a feared Western legend by the time he arrived in Dodge City, Kansas, in September 1878, several years before Wyatt Earp would become famous.

The local newspapers would note his visits to the city, often describing his daring deeds. He was described by the Kinsley [Kansas] Graphic (Kinsley is 36 miles northeast of Dodge City) on December 14, 1878, as: “His appearance is striking. Tall, straight as an arrow, dark-complexioned, carries himself with ease and grace, gentlemanly and courteous in manner, never betraying by word or action the history of his eventful life.”

An often written-about event was the “showdown” between Wyatt Earp, Dodge City Assistant Marshal, and the self-proclaimed “shootist” from New Mexico. According to the stories, Allison planned to protest the treatment of his men by the Dodge City marshals and was willing to back his arguments with gun smoke. In the charged atmosphere of Dodge City, this might have been a very real possibility.

At the time, Dodge City had a reputation for being hard on visiting cattle herders, with stories circulating that cattlemen had been robbed, shot, and beaten over the head with revolvers. Indignant, the cattlemen responded that the marshals were all pimps, gamblers, and saloon keepers.

As a regular practice, Dodge City authorities always disarmed the cowboys when they arrived in Dodge City, however, if one got by and went for a gun, he was immediately shot down by the Dodge City marshals. George Hoyt, who had at one time worked for Clay Allison, had been shot to death while shooting a pistol in the air in the streets of Dodge City.

There are several versions of the story of the showdown. Some say that Allison and his men terrorized Dodge City, while Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson fled in fear. Others, including Wyatt Earp himself, would say that Earp, along with Masterson, pressured Allison into leaving. The most likely version of the account, however, is that Allison was talked into leaving by a saloon keeper and another cattleman, with little or no contact with Wyatt Earp at all. This version, which was later written about by famous Pinkerton Detective Agent Charles Siringo, who was present during the event, is most likely the true story.

Historians basically surmise that Allison might have come to Dodge City looking for trouble, but nothing really happened. While Allison and his men went from saloon to saloon, fortifying themselves with whiskey, Earp and his marshals began to assemble their forces. But in the end, Dick McNulty, owner of a large cattle outfit, and Chalk Beeson, co-owner of the Long Branch Saloon, intervened on behalf of the town, talking the gang into giving up their guns.

By 1880, Clay had moved to a ranch in Hemphill County, Texas, next door to his brother-in-law, Lewis Coleman. On January 17, 1881, it was stated in a local newspaper that “three of the Allison brothers moved on the Gageby.” Though John and Monroe may have joined Clay at some point, they continued using their Colfax County ranch for several years.

While in Texas, Allison’s reputation was kept alive by reports of his unusual antics. Once, he was said to have ridden nude through the streets of Mobeetie, whooping and hollering and declaring that drinks were on him at the local saloon.

When the shocked ladies called upon the sheriff to intervene, the officer demanded that Allison get down from his horse. Instead, Allison spurred the steed to full speed up and down the main street, then got off his horse, leveled his gun at the sheriff, and marched him into the bar. He then forced the sheriff to drink until he couldn’t stand up and, satisfied, went back to his horse.

In October 1883, Allison sold his ranch in Hemphill County, and the couple returned to the Seven Rivers region in New Mexico, where Clay continued to ranch. On August 9, 1885, Clay’s first daughter, Pattie Dora, was born in Cimarron.

In the summer of 1886, Clay had just finished a long, hard trail drive that took him to Cheyenne, Wyoming. Having a terrible toothache, he visited a local dentist, who, having already heard of Allison’s reputation, trembled with the thought of who was in his chair.

The dentist started working on his tooth, but Clay soon realized that it was the wrong tooth, pushed his way out of the dentist’s chair, and went to find another dentist. After the new dentist pulled the correct tooth, an angry Clay returned to the first dentist, held him down in the dental chair, and pulled one of his molars with a pair of forceps. Attempting to extract a second, the dentist’s screams were heard, and men came and pulled Allison away from the petrified dentist.

Shortly thereafter, the couple moved again, this time to Pecos, Texas, 50 miles south of the New Mexico line. On July 1, 1887, Allison was hauling a load of supplies to his ranch from Pecos when a sack of grain fell from the wagon.

Trying to halt its fall, Clay fell from the heavily loaded wagon, and in the next instant, the wagon wheels rolled across him, breaking his neck. As the horses reared and lurched forward, his neck was further crushed by the heavy buckboard, almost decapitating him.

Unlike most gunfighters of the time, the 47-year-old Allison didn’t die in a blaze of gunfire or at the end of a hangman’s noose but rather stuck under his own wagon forty miles from town. Clay Allison was buried in the Pecos Cemetery the day after his death, where hundreds of people were said to have attended his funeral.

His second daughter, Pearl Clay, was born seven months after his death. Later, Dora married for a second time and moved to Forth Worth, Texas.

Just one month after Clay Allison’s death, his brother Monroe Allison died of a heart attack at his Gageby Creek ranch on August 5, 1887. The 43-year-old bachelor was found next to his horse. John Allison, after a brief and painful illness, died in Clifton, Tennessee, on January 7, 1898, leaving a wife and four daughters. He was not quite 44.

Clay Allison’s life was certainly an adventure, from cattle rustling to lynching to coining the term “shootist.” But his life was also marked by much success as a rancher. Whether Clay Allison was a gentleman or a villain is a question that many have never settled in their own minds.

On August 28, 1975, in a special ceremony, his remains were re-interred in Pecos Park, just west of the Pecos Museum.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023.

“I have at all times tried to use my influence toward protecting the property holders and substantial men of the country from thieves, outlaws, and murderers, among whom I do not care to be classed.”— Clay Allison, in response to a Missouri newspaper which reported him with 15 killings under his belt.