Shooting Times Magazine

In The West Wing of a secluded, tile-roofed Spanish home in San Antonio, Texas is a room that is one of my favorite retreats. It’s a large room, carpeted with the rich hides of Polar and Kodiak bears and tigers. A long setee is draped with zebra hides that prickle your back when you sit down for a drink and some talk with the man of the house. Pairs of elephant tusks stand close to bookcases and a maze of racked rifles and shotguns of every description. The walls are spiked with such a forest of mounted heads and horns that the whole effect becomes blurred, and the guest concentrates on the host, who leans casually behind a big wooden desk.

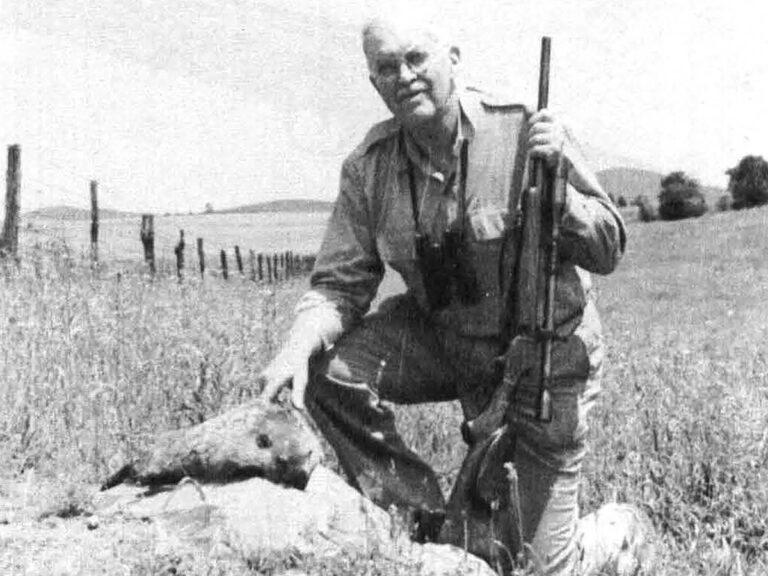

He is a ruddily healthy man of indeterminate middle age, his compact body kept hard by constant physical activity, his hands those of a working man. He looks at you with a direct blue gaze that would raise your guard if it weren’t with a soft chuckle as he asks about your health, your family, and the advancement of your career. The smile that accompanies the chuckle is partially hidden by a drooping roan moustache, and overshadowed by the belligerent nose of a Roman centurion.

He is Col. Charles Askins, my longtime friend, and one of the most interesting – some say the most controversial – men you are likely to meet anywhere in this last of the 1900s.

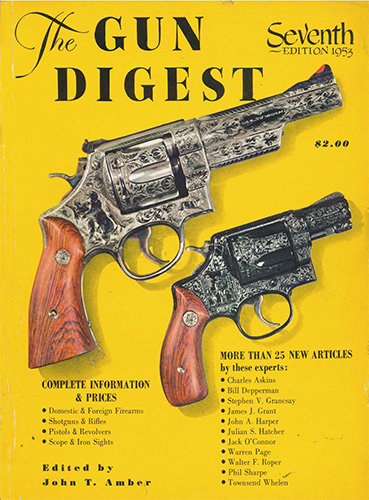

Since you are sufficiently bemused by firearms to be now reading the pages of Shooting Times, you know Askins as a prominent writer whose work has appeared in about every gun publication. You might know that he is the son of the late Maj. Charles Askins, the best authority and writer on the subject of shotguns that this country has produced. The salty, knowledgeable, and for the hidebound, often outrageous stories penned by this man of guns are explained and mitigated by a background that would shame the plotting efforts of the most imaginative novelist.

Askins is living proof that the use of guns can be a way of life. Reared by a father whose living came from guns, he worked first as a forest ranger, spent 10 years in the U.S. Border Patrol in rumrunning days when a gunfight a night was the rule of thumb, won the National Pistol Championship, then moved into the U.S. Army for 22 years as an ordinance officer. During those decades of service to his government he managed to allot time for hunting trips on almost every continent in the world and became an internationally recognized big game hunter.

Since his retirement from the army nine years ago, the restless Colonel has continued to combine shooting and writing in an enviable mode of living that has given him material for more than 1000 magazine articles and seven books.

When Askins was born in 1908, his father was a writer and dog trainer. The elder Askins had moved into Ft. Niobrara, a Nebraska military post, to train some bird dogs for a wealthy client and incidentally to brush up on his prairie chicken shooting. Literally cutting his teeth on upland game, the two-year old Charley was packed off to Oklahoma in 1910, and lived near the town of Ames, on the Cimarron River, until 1927.

Ames was also home to a friend of the Askins’ named Charles Cottar, who was doing well as a grain buyer. In 1912 Cottar went to Africa and hunted for nine months. Seeing its potential, he moved his family there in 1913 to spend the rest of his life as a farmer, miner, and professional hunter.

After World War I, Cottar toured the United States showing motion pictures he had made of African game, and doing much to stimulate the interest in African hunting that endures to this day. Encouraging dangerous game to charge him made for better films and Cottar’s foot was crippled by a leopard. A rhino did the same for an arm. Many years later he was killed by an attacking rhino.

When Askins was 15, Cottar invited his father to bring him for a summer’s hunt in Kenya. Feeling that nothing should stand in the way of a good shoot, the Askins team caught a boat and sailed for three weeks to arrive at Nairobi and join their Oklahoma friend.

This was before the days of motorized and refrigerated safaris, and the party left Nairobi afoot, with a Model T Ford pickup carrying their camp outfit. Walking 10 miles a day, the hunters roamed the plains for two months, living off the land. Charley’s dad had fetched along a then-new .35 Newton and a .30-06 Springfield, while Cottar carried a Winchester 95 lever action in .405 caliber.

The teenaged rifleman confined himself to feeding the safari crew with an abundance of the varied antelope, while his dad and Cottar accounted for five lions. On the trip back to the states, the youthful hunter must have reflected that a tedious six weeks on a slow freighter was a small price for such a summer.

At 19 Charley upped stakes and went to the Flathead Forest in Montana, where he hired on as a temporary employee with the U.S. Forest Service during the fire season. He later performed the same work on the Jicarilla Indian reservation in northern New Mexico, interspersing these seasonal chores with hard toil in logging camps.

The year 1929 found him a full-fledged forest ranger, in charge of the Vaqueros Ranger District in the Kit Carson National Forest. This is where Charley began the intensive pistol shooting that was to make him a national champion.

The Vaqueros District was badly overgrazed by a herd of 2600 wild horses that threatened to strip it of vegetation. Game was suffering from lack of forage, and a burgeoning population of mountain lions waxed fat, killing horses and game animals indiscriminately.

Charley coursed the lions with a big pack of dogs. To feed these hounds he killed the scrubs among the wild horse herd, getting lots of practice with the .45 auto he packed in that period, as well as a variety of rifles.

Tiring of what he likens to “a sheepherder’s existence,” Askins succumbed to the siren call of adventure. His old friend George Parker was serving as a border patrolman in El Paso and having a fine time running down the smugglers who were shotgunning Mexican booze into the bone-dry States. Parker’s exciting letters caused Askins to ride down to El Paso, where he joined the Border Patrol in March 1930.

The evening of that first day on the job, the young horseman was dispatched into the Franklin Mountains west of town to bring out the body of a dead smuggler on a pack burro. The contrabandista had elected to shoot it out when challenged by officers, and his earthly remains suggested to Charley that he was in for some busy times. He was.

Several weeks later he and his partners were lying in wait as five smugglers sneaked their contraband up an alley-way leading from the border river. As in most of these encounters, they in darkest part of the night, and were armed and ready to shoot. In his new book, Texans, Guns, and History, Askins describes what happened next.

“When they got to within nine steps of us we challenged. All hell broke loose! The cholo in the lead had a 10-gauge, both hammers back but the gun unfired. After the scrap I gathered up this gun and after carefully lowering the dog-eared hammers, broke the gun open and found it was loaded with Winchester Hi-Speed No. 5 shot. If he could have set off those two charges before he took the double load of my buckshot he’d have evened the odds considerably!”

This was one of many times that Askins had to use his guns in river gunfights during that period when newsmen on the El Paso Times would phone Border Patrol headquarters each morning to inquire, “Who got shot last night?”

Not all of Charley’s gunwork was so grim, and the stories he seems to prefer to tell involve occasions on which he missed his target.

One misty morning near Strauss, N. M., the young Patrol Inspector cut sign on two sets of tracks moving north. The drizzle made seeing difficult, but he stayed on the tracks, sixgun in hand as they led him to a camp where two people lay bedded under a tarp.

Southpaw Charley flipped the tarp off the suspects with his right hand, leveling his revolver with his left. One man sat upright, aiming a carbine at the Askins belly. Startled, Askins fell back, firing as he did. His slug went over the bad guy’s shoulder blasting a big hole in the wet ground and causing immediate capitulation.

It was miss that Charley was dammed about. The two “smugglers” turned out to be a standard American hobo and his wife, on the bum toward California. When for some inexplicable case the “Bo” pointed his weapon at the future pistol champ, he didn’t know how close to death he was. The “carbine” turned to be a hickory pick handle.

After Charley had a couple of months service under his belt, it was decided that tryouts would be held to find the five best pistol shooters in the Border Patrol’s El Paso District. These five would make up a pistol team which would go forth and do battle with civilian competitors and teams from the 7th and 8th Cavalry regiments. No one was surprised when Charley shot number one among the border guards.

In 1932 the 8th Army Corps promoted a pistol tournament in El Paso that was big doings for that Depression year. It attracted top shooters from the entire Corps Area, which included Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico.

After two days of shooting, the El Paso Border Patrol team had captured the team championship, Charles Askins had won each individual match, and his pretty wife, Dorothy, had walked away with the trophy in women’s competition.

In that year, Charley’s match guns included a Colt Woodsman .22 with weighted barrel, a heavy Colt shooting Master in .38 Spl., and a commercial M1917 Smith & Wesson revolver in .45 ACP. He was shooting these guns when he lost the 1932 Texas pistol championship to Air Corps Lt. Charley Denford by one point.

In 1933, Askins won the Texas Championship. The next year, 1934, was a hot one for the Los Angeles police, and one of their team took home the Texas cup. For ’35, ’36, ’37, and ’38 the champ of Lone Star State was Charles Askins.

By 1936, Askins had been designated Chief Firearms Instructor for the entire U.S. Border Patrol and moved from his little New Mexico station at Strauss to the district headquarters in El Paso.

Firing a .45 in the National Individual Match at Camp Perry that year, he flubbed his slow-fire string, shooting “a big, fat 80, with a four in the string.”

“This completely relaxed me,” says Askins, “and I knew nothing could win for me then.”

With the pressure off, he went on to shoot a 98 timed and a 98 rapid, winding up with a score of 276. he won the match.

Introduced at Camp Perry in 1937 was the first aggregate match – a combination of the scores of .22, centerfire, and .45 guns, and a much more meaningful test of shooter and guns than had previously been posed. The NRA paid money prizes that year, along with medals and a trophy.

Askins won the aggregate, received $8.56 cash, a medal, and the promise of a trophy which somehow was never delivered. He now wishes the $8.56 had been withheld, too, since it was later ruled that his acceptance of it disqualified him as an amateur, and he was not permitted to try out for the Olympic pistol team.

That year at Perry there was an incident which Askins describes as having “…been played up, discussed, and gotten me criticized ever since it happened. It was during a rapid fire match and I had a misfire.

“The range officer watched as I opened the gun, and there were six cartridges in the cylinder; the rules called for only five. This was a violation of the rules. You couldn’t put six rounds in your gun. I’d done this because on a rapid-fire match if you ever let that hammer slip out from under your thumb the cylinder will roll by and then you won’t get off five shots. So, in violation of the rules as the existed then, I had six cartridges in my gun.”

The NRA range officials did not challenge this action, and allowed him to shoot the string over for record.

In spite of the acceptance of NRA officials of this insignificant overstepping of the rule book, someone complained so vociferously to Askins’ superior officers in the Border Patrol that an investigation was initiated by that service. The upshot was that the 1937 all-around pistol champion was punished by not being allowed to shoot on the Border Patrol team in 1938.

The champion shot at his own expense as an individual in ’38, winning the high aggregate on the All American Team after placing first in .22, third in centerfire, and fifth in .45 events.

Askins was returned to grace in 1939, and reinstated tot the Border Patrol team. He promptly became the center of another controversy. Today’s competition rules provide for three phases of pistol shooting: .22 Long Rifle caliber, any centerfire (.32 caliber or larger), and .45 ACP caliber. Charley Askins is probably personally responsible for their addendum in parenthesis after “centerfire.”

In 1939 the rule was simply “any centerfire” for the second event. Most shooters banged away with .38 Spl. revolvers, a few with .32 S&W Long wheelguns. The .38 Spl. automatics so popular today were unheard of.

Then and now, competition pistol shooters agree that automatics are easier to control in timed and rapid fire than revolvers, and that small calibers are easier than larger ones.

Askins thought so, too, and did something about it.

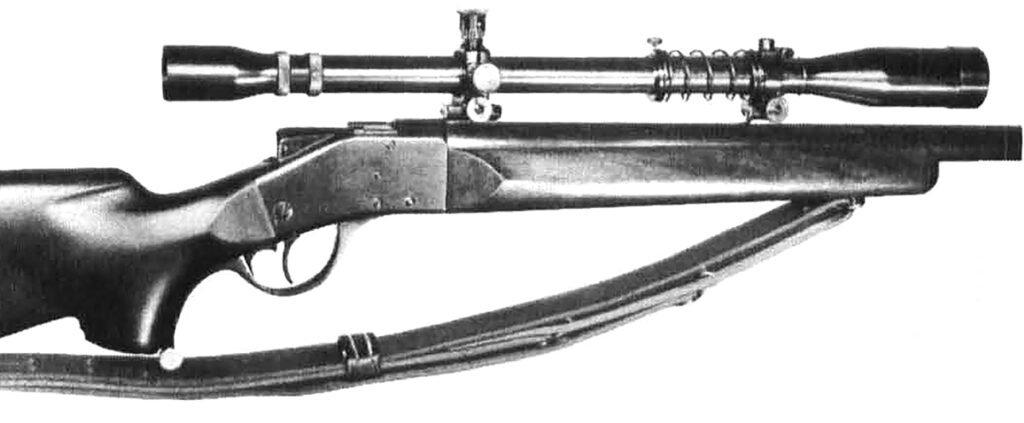

The almost-extinct 5.5 Velo Dog was an inexpensive, nine-shot French revolver that still occasionally cropped up in Mexico and Latin America in those days. An El Paso hardware dealer showed Charley some of the scarce ammunition that remained after exporting most of his stocks across the Rio Grande. Struck by the dimensional similarity of the tine centerfire cartridge to the .22 Long Rifle shell, Askins formed a beautiful scheme.

First he bought all the 5.5 Velo Dog ammo the dealer had. Then he contacted Frank Kahrs, the shooting promotion director of Remington Arms, who sent the last 2000 rounds of Velo Dog the factory had in stock, and seemed glad to be rid of them. As Askins now gloats, “I had control of the entire remaining supply of Velo Dog ammunition.

J.D. Buchanan was a well-known West Coast pistolsmith, and an Askins friend. Charley shipped him a new Colt Woodsman .22 and a few rounds of Velo Dogs, with instructions to mate the two. In a twinkling, Buchanan altered the Woodsman’s firing pin to a centerfire, changed the extractor to handle the somewhat thicker rim of the French shell, and rechambered the barrel to accommodate the slightly larger diameter and the shortened Velo Dog case. While he was at it he added an adjustable weight and custom sights.

While this was going on, Charley got busy on the ammo. He pulled bullets and dumped the powder charges of the Dogs. He trimmed the cases to .22 LR length and reprimed them. He re-charged with tiny measures of Dupont #5 pistol powder, and seated .22 Long Rifle bullets. Askins was now in the .22 center fire business.

The new Woodsman shot just as well as any .22 rimfire of its day. This gave Charley an advantage of several points over the best centerfire shooters in the country who had to use revolvers.

Word got out about Charley’s scandalous little gun, and he was again under as cloud. Old friends came to advise him that it would be “unethical” to shoot the imaginative .22 against shooters who had only .32 and .38 wheelguns.

The Border Patrol brass got wind of the affair and Charley remembers a letter from them forbidding him to shoot the pistol in the National Matches. Knowing Askins, I would estimate that his neck bowed larger by several sizes.

Range officials examined the offending Woodsman minutely and could find no regulation it abused, until one book man, sharper than the rest, found that the front and rear sights were a hair too far apart to meet maximum sight radius requirements. Askins hastily remedied this by knocking off the Buchanan sight and rather crudely reinstalling it farther forward with solder.

The day came, and Charley obstinately marched to the firing line at Camp Perry. Behind him, “The Border Patrol brass all gathered to bear witness that I had shot the gun against orders,” he smilingly recalls.

The gun shot well and Charley shot well, although not good enough to win the match. At the end of the day he sat down and wrote a letter of resignation to the District Director in El Paso.

“I resigned from the Border Patrol from a feeling that they were going try to dictate how I was to shoot, and I wasn’t going to stand still for it. They had a point and I felt I had a point, too.”

So ended nine years and nine months of service.

By this time, Askins was writing a considerable amount of gun-related material, having published on book, Art of Handgun Shooting, and being employed as firearms editor for Outdoors magazine.

Askins’ father had moved to the Rio Grande Valley at his son’s urging, continuing his studies of firearms and to act as firearms editor of Outdoor Life and later Sports Afield. When asked if his dad had encouraged him to become a writer, Charley shakes his head.

“It was just a good opportunity to trade on his name. If I could get something into print, people might think it was written by the real authority.”

With whatever impetus, after he left the Border Patrol Askins continued to live in the valley above El Paso, “eking out an existence” writing for Outdoor Life, Field and Stream, and The American Rifleman.

He had been a non-commissioned officer in the National Guard since 1930. When the Guard was called to duty in 1941 he contacted his friend and fellow shooting authority, Gen. Julian S. Hatcher, asking for a commission into the regular army.

Maj. Gen. Kenyon Joyce of the 1st Cavalry Division and Col. Caswell gave him their hearty endorsements, and he was give a direct commission as a 1st Lt. Of ordnance in February 1942, reporting for duty at the Aberdeen Proving Grounds.

Ninety days later Lt. Askins left the States with Patton’s 2nd Army Corps, and plunged into the invasion of Africa. There the inexperienced logistics planners found that they could not supply their depots with ordnance as fast as it was being used up.

It was necessary to recover and overhaul equipment abandoned in the field, and Askins was assigned as a battlefield recovery officer in command of provisional company. This company and others like it were eventually found so effective that they were permanently placed in the Table of Organization.

Askins recalls: “We slept all day and worked all night” to avoid enemy fire and ambushes. Under cover of darkness, he and his men reconnoitered, located abandoned vehicles and weapons, and found means of returning them to U.S. lines for repair and reissue.

By the time of the Sicily invasion, Askins had been promoted to executive officer of an ordnance battalion. Asked if he carried any personally owned weapons during his wartime service, Charley reminisced that in Africa and Sicily he had packed a Buchanan-accurized .45 auto.

After Sicily he returned to the States for five Months, then shipped out again for the invasion of the Continent. When he did he left his .45 at home and took along the revolver he had carried in the Border Patrol, a Colt New Service .38 Spl. Askins still has this gun, and it is quite beautiful, carrying a red-posted King rib and adjustable rear sight on its four-inch barrel, and carved ivory stocks. The front of the trigger guard has been cut away.

Knowing Charley’s predilection for the auto pistol, I asked why he had changed to the sixgun in the middle of the war. He answered that he doesn’t remember now what the reason was, but that he was fond of the Border Patrol gun.

He was carrying this sixshooter, loaded with high speed, metal-piercing, Winchester ammunition while searching a house in a village on the Rhine plains. He heard someone making a hasty exit, and ran to a side door in time to see a German with a pack on his back making a dash for the next house.

Askins “let drive” with the .38, its bullet passing through the pack and into the German’s chest. After making certain there were no more Heinies in the house, he loaded the wounded Nazi onto the good of his jeep and drove him to an aid station.

In the town of Schmidt, on the Ruhr River, Charley became bored with what he considered his sedentary existence and borrowed an M1 for a bit of sniping.

Local GIs, happy with the unofficial ceasefire they shared with the seemingly acquiescent Krauts across the river, were chagrined when Askins moved into a second-story room, stood well back from the shot-out window, and commenced to pick off enemy targets of opportunity.

After three days of this his sport ended when German mortars found his hiding spot and sent him running for more substantial comer. It is doubtful that his comrades were sorry that his idyl had terminated.

At the war’s close, he was discharged as a major, immediately signing on as a field editor of Outdoor Life. After nine months of the traveling and public relations work involved in the new job he tired of it, and accepted a regular commission in the army. In July, 1946, Maj. Askins reported for duty with the 1st Army and was sent immediately for training with the 82nd Airborne Division at Ft. Monroe, Va.

While conditioning to the tough life of a paratrooper, Askins renewed his interest in pistol shooting after a separation of eight years. He believed that the Army should have one pistol team, as had the Marines and Navy. As of then the Army fielded teams from all its services, such as Cavalry, Infantry, and Engineers, thus spreading the top shooter apart on separate teams.

He was permitted to nominate shooters for tryouts, and got together 10 or 12 of the entire army’s best prospects for training and elimination at Ft. Bragg. A team was selected and sent to the National Midwinter Championships, where Sgt. Joe Benner won the individual championship.

Charley shot on this team. By this time he was 40, and could look back on an average of 34,000 shots per year, by actual records, that he had fired in his pistols between 1930 and 1940, a total of a third of a million rounds. His interest was jaded, and he gave up match shooting.

“I just couldn’t fire myself up to the degree of enthusiasm for the necessary practice. Practice was just a hell of a lot of hard work.”

By this time the ex-National Champion had accumulated 534 medals and 117 trophies in state, regional, and national competition.

The next few years were pleasant for the Askins family. Ordered to Spain in 1950, Charley served in the U.S. embassy as an assistant Army attaché, his arms expertise being well utilized as he made a study of the Spanish military posture, its arsenals and its assets.

He loved the Spanish people and gloried in the fine partridge hunting his tour afforded him. During the war and this postwar Spanish service, he found time to hunt in Portugal, Morocco, Angola, the Sahara desert, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, and Botswana.

He topped off his four years in Spain by graduating from the Spanish Army’s parachute school. In passing he also picked up the National Skeet Championship of Spain.

Charley returned in 1954 to the Combat Development Section of the Infantry School at Ft. Benning, moving to the 18th Airborne as an ordnance officer. In 1956 he was assigned to the Vietnamese army as Chief Instructor of Firearms.

In contrast to the hellhole it is today, Nam was pleasant between wars, the French having just been deposed. There was not even any guerrilla activity during Askins’ occupancy, and he traveled the length and breadth of Vietnam, alone in a jeep.

The French army, rulers of the country for 75 years, didn’t believe in marksmanship training, and had erected no ranges. Charley spent a year building range complexes for each of the 10 VN divisions. He also enjoyed some of the finest big-game hunting of his life.

In the jungles of the little Africa, Askins confronted the gaur, a buffalo larger than the African Cape buff, weighing up to 3000 lbs., and the largest of the five varieties of buffalo in the country. He found the gaur to be shy, but dangerous when wounded, needing plenty of lead to stop him.

There was an abundance of elephant, bad tempered because of continual harassment by the natives. There were Bengal tigers and a smaller tiger which was found along the South China Sea. Leopards, wild boar, Asian bear, and seven species of deer roamed this rifleman’s paradise. Charley’s shotguns took a dove that is the image of the U.S. breed, along with the jungle fowl, the progenitor of the domestic chicken.

Anticipating this good game country, Askins carried seven guns and 2600 cartridges to Vietnam. He had one of the first M70 Winchesters in .458 caliber, along with a lever-action M71 Winchester that was made up by an Alaskan gunsmith named Johnson, who rebored it from .348 to .450 caliber. The rest of the Askins battery included a Savage M99 .358, Browning .22 autoloader, Winchester M12 pump 12 gauge, Browning two-shot auto 12 gauge, one of the first S&W .44 Magnums, a Ruger standard .22 auto pistol, and a little Walther .22 PPK.

He was joined for a two week’s hunt by his Arizona friend, George Parker, whom he had known since the 1925 rifle matches at Camp Perry. The preponderance of his hunting was done in the company of a Chinese sportsman, Ngo Van Chi, who arranged for guides and packers from the Moi tribe of highland savages.

Chi’s safaris were outfitted with 20 elephants, each with a mahout and assistant mahout. Each man received a wage of $1 a day. The Moi tribesmen each demanded and were daily paid one liter of rice wine, three ounces of tobacco, and one pipeful of opium. This was the standard arrangement for safari crews in that area, but Askins found the handling of the wine a definite inconvenience. “We had to pack all those damned bottles – 25 liters of wine a day.” In spite of their peculiar wage negotiations, Charley heartily enjoyed the company of the Mois.

He completed his Vietnamese duties by going through VBN parachute school before retuning to an assignment with the 4th Army Headquarters at Ft. Sam Houston, San Antonio, Tex.

While he alludes infrequently to his paratrooper experiences, I have pried from him that he has made 138 jumps. One of these was with an eight-man stick of hardies who were helping him celebrate his promotion to full colonel. Charley banged up his back and foot on this one and as a result occasionally perches on a rubber doughnut while he types. He doesn’t say, but simple arithmetic tells me that he was more than 50 when he took that dive.

Askins retired from the Army in 1963, and continues to shoot, hunt, and write. His name has appeared in many gun and outdoor magazines and is shooting editor of Guns Magazine and Shooting Industry. He has also written a shooting column for Army Times since 1958. Texans, Guns, and History is the latest of his well-received books.

Charley has made 17 hunting trips to Africa, and is planning another for the summer of ’72. He has hunted twice in India, six times in Alaska. He has killed the game of Mexico, and scores all the Africa “Big Five” among his trophies. Along with tiger, gaur, and Sambar, he has bagged five Kodiak and two Polar bear.

Charley has quit bear hunting in the interest of conservation, and entertains no plans to tackle the category of game sheep. While he hasn’t eschewed big-game hunting, Askins favors the shotgun nowadays, knowing that days of hard stalking after a big game animal might offer a single shot, while the bird hunter may shoot 20 or 30 rounds in an afternoon. After a moment’s pondering, he admits that his favorite quarry is the bobwhite quail.

To stay in good form, Askins shoots almost every day. He arises at 5 a.m., cares for his horses, runs his dogs. A bit of riding, a couple of hours of shooting, and he ready to devote the rest of the day to writing and answering correspondence.

Charley regularly practices with an air rifle, preferring the Model 150 Anschutz. Once a week he drives to Ft. Sam Houston for a couple rounds of skeet. His centerfire rifle practice is all offhand – to stay in trim for game shooting. Pistol practice comes only about once a week – enough to keep his hand in and to beat Skelton whenever he feels like it.

He stays in excellent condition by being active in outdoor sports. He has never smoked.

I once asked Askins how he felt about match pistol shooters who took a toddy for their nerves, and he told me of that Texas match in 1934 when the Los Angeles police beat the pants off him.

Between relays, the L.A. cops would retire to the old Cadillac hearse in which they traveled, and draw the curtains. Moments later they would emerge and clobber the next relay. Charley sent out spies and learned the back of the hearse was stacked high with gin. From then forward he attended his matches fortified with the same brand.

Askins is concerned about the future of hunting. He feels that despite the rosy picture painted by some conservationists, the increase of the game population cannot keep pace with the human population explosion. With game under graduating pressure he predicts that game farms will play a major role in U.S. hunting in the coming years. African hunting, he surmises, is doomed unless poaching can be controlled, and domestic animals be substituted as a source of meat for the swelling populace.

On my last visit to Askins’ diggings in San Antonio, I noticed a large sheet of new tin that had been nailed around the bole of a big tree near his kitchen window. I asked my curious question, and the gunfighter and killer of dangerous carnivore explained, “My cats were climbing the tree and catching the baby birds. Had to do something.”

If Charley Askins had been born 100 years earlier he would have been a mountain man, and Indian scout, a buffalo hunter, or a horse soldier. As it is, close now to the end of the 20th century, he has lived the kind of life that boys think they’re going to live and that most old men wish they had.

May his breed continue.

The detail on this piece of work, almost real in expression and uniforms.

The detail on this piece of work, almost real in expression and uniforms.