Robert Downey, Jr. is one of the most esteemed actors of his generation. His depiction of Tony Stark as Iron Man across 10 big-budget superhero movies became iconic. I once read a commentary by a British film critic who said that Downey’s English accent in the Sherlock Holmes films was the only example of an American playing a Brit that he felt was in any way believable. What makes that so remarkable is that Downey never took acting lessons. He just got in front of the camera and did his thing. He’s a natural.

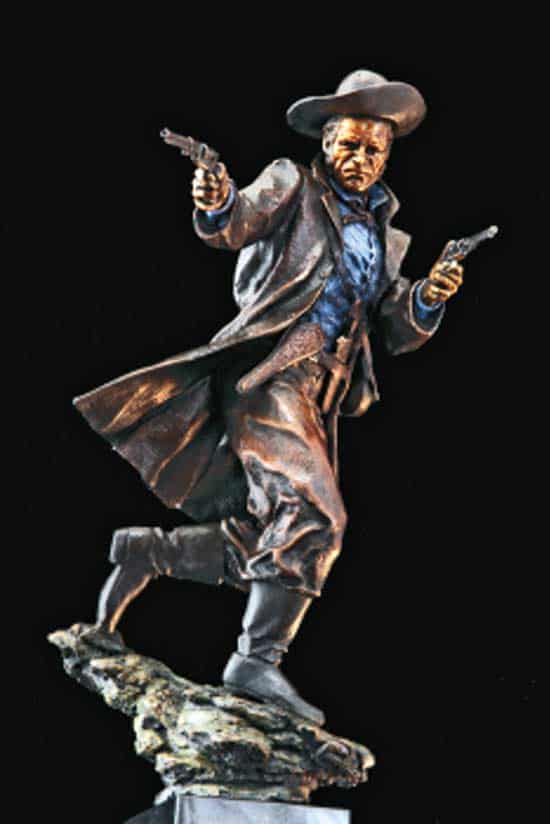

There was a time when this was the rule rather than the exception. John Wayne’s natural swagger certainly could not be learned. Back in the Golden Age of Hollywood, actors were not necessarily mushy, fragile prima donnas. They often were drawn from the ranks of truly manly men out in the real world. Principle among them was one Peter Ortiz.

Filmography of a Hero

Peter Ortiz starred in 27 films and two television series. His filmography includes such classics as She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Retreat, Hell!, The Outcast, Twelve O’Clock High, Wings of Eagles, and Rio Grande. Ortiz brought a gritty realism to the sundry roles he played on screens both large and small. That’s because he was arguably the baddest man ever to grace the silver screen.

Pierre Julien Ortiz was born in New York in 1913. His mother was of Swiss stock, while his dad was a Spaniard born in France. He was educated at the French University of Grenoble. Ortiz spoke 10 languages. In 193,2 at age 18, he joined the French Foreign Legion.

The Foreign Legion is comprised of some legendarily rough hombres. Peter Ortiz thrived in this space. He earned the Croix de Guerre twice while fighting the Riffian people in Morocco. In 1935, Ortiz turned down a commission as an officer in the Legion to travel to Hollywood and serve as a technical advisor for war films.

Proper War

We modern Americans often overlook this fact, but World War II burned on for a couple of years before we got involved. As soon as the shooting started, Ortiz left Hollywood and returned to the Legion as a sergeant. He soon earned a battlefield commission and was wounded while destroying a German fuel dump. He was captured soon thereafter but escaped through Portugal, eventually making it back to the United States.

War was a growth industry in the early 1940s, and American citizens with combat experience were invaluable assets. Ortiz enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps in June of 1942 and earned a commission as a Second Lieutenant 40 days later. He made captain by year’s end and was deployed to Tangier, Morocco, assigned to the Office of Strategic Services. The OSS was the predecessor to the CIA. Captain Peter Ortiz was now officially a spy.

Undercover Ops

Ortiz was wounded badly, recovered, and then parachuted into occupied Europe several times. He repatriated downed Allied flyers and helped organize French Underground units. In August 1944, he was captured by the Germans. He survived torture by the Gestapo and somehow avoided execution. In April 1945, Ortiz’s POW camp was liberated. Now a Lieutenant Colonel, he made his way back to Hollywood to pick up where he left off.

In 1954, Southeast Asia was heating up, so Lt. Ortiz volunteered to return to active duty. However, by then, he was more than 40 years old and sort of famous. The Marines turned him down but promoted him to full Colonel in retirement.

Decorations

We’ve glossed over this guy’s amazing career. He was awarded an Order of the British Empire (OBE) by the government of England. He earned both the Navy Cross and the Purple Heart, each twice. The Navy Cross is our second-highest award for valor, right after the Medal of Honor. Here’s an excerpt from his first Navy Cross citation:

“Operating in civilian clothes and aware that he would be subject to execution in the event of his capture, Major Ortiz parachuted from an airplane with two other officers of an Inter-Allied mission to reorganize existing Maquis groups in the region of Rhone.

By his tact, resourcefulness and leadership, he was largely instrumental in affecting the acceptance of the mission by local resistance leaders, and also in organizing parachute operations for the delivery of arms, ammunition and equipment for use by the Maquis in his region.

Although his identity had become known to the Gestapo with the resultant increase in personal hazard, he voluntarily conducted to the Spanish border four Royal Air Force officers who had been shot down in his region, and later returned to resume his duties. Repeatedly leading successful raids during the period of this assignment, Major Ortiz inflicted heavy casualties on enemy forces greatly superior in number, with small losses to his own forces.”

Ruminations

There were two Hollywood films that were based upon his personal adventures. 13 Rue Madeleine came out in 1947. Operation Secret hit theaters in 1952. Ortiz had one son, Pete Junior, who served as a Marine officer himself, retiring as a Lieutenant Colonel.

Of his dad, the younger Marine said, “My father was an awful actor, but he had great fun appearing in movies.” Colonel Peter Ortiz might not have been the greatest actor of all time, but he was an amazing warrior.

United States

Navy Cross with gold star

Navy Cross with gold star

Legion of Merit

Legion of Merit Purple Heart with gold star

Purple Heart with gold star

American Campaign Medal

American Campaign Medal European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal

European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal World War II Victory Medal

World War II Victory Medal Marine Corps Reserve Ribbon

Marine Corps Reserve Ribbon Parachutist Badge

Parachutist Badge

United Kingdom

Officer of the Order of the British Empire

Officer of the Order of the British Empire

France

Chevalier of the Legion of Honor

Chevalier of the Legion of Honor Médaille militaire

Médaille militaire Croix de guerre des théâtres d’opérations extérieures with bronze and silver stars

Croix de guerre des théâtres d’opérations extérieures with bronze and silver stars Croix de Guerre 1939-1945 with two bronze palms and silver star

Croix de Guerre 1939-1945 with two bronze palms and silver star Croix du combattant

Croix du combattant Médaille des Évadés

Médaille des Évadés Médaille Coloniale with the campaign clasp: “MAROC”

Médaille Coloniale with the campaign clasp: “MAROC” Médaille des Blesses

Médaille des Blesses 1939–1945 Commemorative war medal (France)

1939–1945 Commemorative war medal (France)

December 19, 1854 was a cold day in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains. Three prospectors carefully traversed a rough trail in aptly named Rocky Canyon in El Dorado County, near the North Fork of the American River.

December 19, 1854 was a cold day in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains. Three prospectors carefully traversed a rough trail in aptly named Rocky Canyon in El Dorado County, near the North Fork of the American River.