or Gordon as a baby!

say I have some issues with this guy? Grumpy

The Practical Combat Carbine- Simple, Light, Effective.

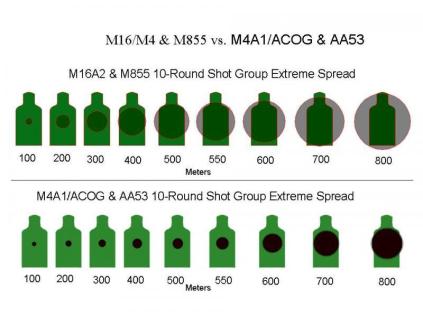

There’s a lot of confusion even among longtime shooters between what a rifle is capable of doing off the bench on a nice controlled square range and what’s actually practical for a serviceable combat weapon. The two really aren’t the same. While tight groups are definitely a plus and a goal to be attained, having a precision weapon in the general purpose role is not always completely necessary to make one combat effective. There’s a happy medium to be found, and getting there is not always hard or expensive. Above all else, it’s the fundamentals of the shooter that make a weapon deadly, no matter what.

One of the really neat things about the past couple decades, firearms-wise, is the real renaissance we’ve seen in weapons development and maximization of potential. Most visibly is this phenomena with the proliferation of the AR-15 platform, but really among all classes of weapons. One can pick up even a lower-tier carbine and have a decent action capable of making solid hits at further distances than many shoot on average. That is, if the shooter is capable. Some of this has to do with the plethora of modern ammo choices out there, some with the advent and precision of CNC machines, and some with the proliferation of free-floated handguards. While the Colt M4A1 series has a mil-spec tolerance of 4 MOA, or a ~4 inch group at 100 meters, and usually easily exceeding this your common off the shelf AR-15 can expect much better than that on average. It begins, however, with the skill of the man behind the trigger.

The same can be said for the huge boom in the Long Range hobby. Lots of people are getting into it and it can be a ton of fun putting steel on target from 500m or more. The ability to squeeze every last fraction of capability is definitely nice. And usually the underlying goal, whether plinking, running 3 gun or Long Range type stuff, is ultimately protection of hearth and home. But the question that comes to my mind is do you really need all of that to make an effective rifleman? The answer is largely determined by the rifleman’s purpose. For a combat weapon, even a designated marksman’s role, it doesn’t necessarily have to be a .5 MOA rifle or even one that really impresses at the range. Gasping for air, I know. Practical accuracy is a different animal from mechanical accuracy. But let’s look at some reasons why.

1. What is the median distance you plan to engage?

For my operating environment, I live in mostly dense forest with rolling hills. The long distance stretches are either pastures, power lines, or highways. From a light fighter’s standpoint, these three amount to the cardinal rule of never walking in the open or crossing a linear danger area with no overwatch. Overwatch, by the way, is not some fancy buzzword to sell you junk but actually is someone on your team hidden watching for muzzle flashes in case you get shot…while you’re crossing in the open or across linear danger areas. They watch over you. That said, my average engagement distance here is under 100m. Are you accurate enough to be lethal within 100m? How about 200m? How about 300m? Do you really need to shoot further than that? Maybe, maybe not. What are the intermediate barriers, i.e. potential cover (rocks, deadfall, etc) between you and where an adversary may fire from? Are you capable of shooting over those same open areas that they may cross?

Average backwoods of NC.

A good way to put this into context is to think of the average shot a deer hunter will make in a given area. Around here, between thick Carolina conifer and hardwood stands, shotguns do just fine for 99% of putting meat in the freezer. Rifles are nice for shooting across cutovers or fire breaks- those open areas requiring a little more range I just warned you about. And how accurate is that Remington 770 or 742 with meat ammo versus a heavyweight barreled Remington 700 5R and precision handloads? Mechanically it wouldn’t make much difference in the woods over relatively short distances. But the weight sure as heck will, regardless of whether you’re a twenty something stud out shootin’ n’ lootin’ or a mid 50s patriarch looking to protect his home. Doesn’t mean that any of these are my personal choice for anything other than hunting game, but the concept is basically the same. Which bring my next point.

2. What is your Weight Threshold?

I knew a guy a while back who had a uber-high end semi-auto AR-10, decked out to the nines, with every cool guy gimmick you can imagine and a giant NightForce 56mm celestial telescope on top. Beautiful rifle, crisp glass. Weighed 18lbs empty and carried like a 4×4 post in the hands. And there’s nothing wrong with that, if you want a high end benchrest-type gun. But that’s a ridiculous and unnecessary amount of weight for a general purpose weapon. For him, making tiny groups at a given distance was a lot of fun. But when it came time to carry it, you’d see him ditch that for his handy WASR-10 that weighs half as much loaded and accomplishes the same task within 100m.

The point is that what feels heavy but tolerable in your hands at the gunstore becomes a boat anchor after carrying it over distances with supporting equipment. Common knowledge usually dictates weight equates superior accuracy, but too much becomes self-defeating. That lightweight AR-15 with a pencil barrel can get heavy too. After a four day cave clearing mission in Afghanistan my M4 felt like a cinderblock. And aside from a PEQ-15, it wasn’t too far removed from the AR-type carbine pictured above. Granted, I was carrying a lot of other equipment including a SMAW-D and several days worth of 5590 batteries (which is like toting around bricks), but the point is that a carbine I intend to fight with needs to remain lightweight to keep me unencumbered. Because you have to keep in mind its purpose- it’s a carbine, after all. On that note, there’s a reason the broad shouldered bubbas get picked to hump the M-240B; it’s big and heavy, and the small guys can’t handle and effectively employ it over long distances. Even the meat eaters get tired though, and shaving a few ounces here and there makes a world of difference when you’re gassed.

3. Remaining Combat Effective- Remember BRAS

The reality of fighting in armed groups is that it is nothing like sitting at a range plinking targets. That’s nice for basic rifle marksmanship, and it’s really important to work on fundamentals. It’s purpose is to confirm zero & dope (Data Of Previous Engagement- a record of ballistic data for that weapon and specific ammo load) and make sure you can hit a target at a given specific distance, hence why most square ranges are referred to as Known-Distance or KD ranges. Square range time is critical, and should be at least a monthly training event for you and your group. But understand it is not the end-all-be-all; its just a foundation for Basic Rifle Marksmanship consisting of BRAS- Breathe, Relax, Aim, Squeeze. For creating and maintaining proficiency this is the proper cadence for trigger control. It’s easy to get right when relaxed and very easy to get wrong any other time. Only training on a 100m square range is a dangerously false sense of security. Only shooting from a bench and calling it good is preparing you for nothing except shooting off a bench. Getting out and humping that safe queen through the woods for a bit is critically more important than making tiny groups from the bench or even shooting fast at stationary targets in the 3-gun stall. You learn the ins and outs of that weapon on a patrol and get to make it better.

You may very well learn that what you can do with a 12lb rifle you can also do with an 8lb rifle, and that 4lb weight saving could make a big difference. If I’m running a .5MOA rifle but it’s a beast to carry with that 20in bull barrel, I may end up being so exhausted after a movement or a quick react to contact that I can’t hit anything with it because I can’t settle down behind the gun. Under duress this will happen to you. If you’re out of shape this will be you. And at that point the rifle’s accuracy is irrelevant. Shooting a half inch at 100m now becomes not even being able to acquire a target in that 14x zoom lens, because you’re spent and can’t think through your situation. Believe me, it will happen to you.

4. “If you can’t do it with irons, don’t bother with optics”

I was talking recently with an old-hand Sniper Instructor who made this comment. It may come as a shock to some of you but I agree wholeheartedly for making new riflemen. The optics themselves make life easy, especially today in the world of precision machining and glass manufacturing that makes even lesser-expensive options fairly high quality. And it can produce decent marksmen in a shorter amount of time because the process of sight-aquire-fire now becomes streamlined. But- and this is a big objection- without the fundamentals of proper marksmanship, an optic of any type does you little good and in some cases might make you worse. If I’m running way more glass than necessary, such as putting a 16×50 on an M4 because it helps me shoot tiny groups off a bench or in the prone, I’m not effective anywhere but in that one scenario. I may very well lose my target on the glass if something throws me off kilter as usually happens in a dynamic environment and I may also have trouble returning to target with any amount of speed. If I back the zoom off but have a second focal plane scope, now my reticle is worthless for any sort of bullet drop or ranging measurements.

His logic is that if I can do it with iron sights, then I have zero problem with optics. The fundamentals are there, along with my confidence. The foundation is laid. Optics of any type are a tool to enhance one’s capability, not a shortcut in training. If Joe knows he can ring steel with irons on his weapon at an average engagement distance, then an optic of any type enhances his capability. He now has confidence in himself and his weapon. And confidence is the difference maker above any piece of kit. So with that said, anyone getting started in rifle marksmanship should begin with iron sights and graduate to implementing optics down the road. Simplicity equals success. Keep in mind this is for basic training purposes; a standard for those new or inexperienced. Additionally, for those simply thinking optics always equate accuracy, buying airsoft-grade trash or even decent glass but a skimpy or improper mounting solution is a recipe for problems in the long run. If it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing right. If you genuinely don’t know, swallow that pride and get some instruction- I promise, it will be worth it.

Mechanical vs. Practical

Mechanical accuracy definitely plays a large role in practical accuracy, but if your fundamentals are trash nothing is going to make you a good shooter. While you’ve read up until now that pinpoint accuracy is not a central requirement in a primary fighting carbine or rifle, good mechanical accuracy is definitely a desirable asset. If my weapon shoots 2 MOA, or a 2 inch group at 100 yards, that means on an average man-sized target at any given distance I have some margin of error to still make solid hits, all things being equal. Anything up to 4 MOA for a general purpose carbine then becomes perfectly acceptable. Even out to 600m this gives us, in theory at least, 24 inches of spread but still perfectly capable of a solid hit if you do your part. But you have to know how to do your part, and that only comes from solid training. But will you need to shoot that far? Probably not in most cases- and only your own situation can determine this. Most often our expectations should be half that distance at the most, but if everyone in your group can make those kinds of shots, then they’ll have no problems engaging closer than that.

Mechanical accuracy definitely plays a large role in practical accuracy, but if your fundamentals are trash nothing is going to make you a good shooter. While you’ve read up until now that pinpoint accuracy is not a central requirement in a primary fighting carbine or rifle, good mechanical accuracy is definitely a desirable asset. If my weapon shoots 2 MOA, or a 2 inch group at 100 yards, that means on an average man-sized target at any given distance I have some margin of error to still make solid hits, all things being equal. Anything up to 4 MOA for a general purpose carbine then becomes perfectly acceptable. Even out to 600m this gives us, in theory at least, 24 inches of spread but still perfectly capable of a solid hit if you do your part. But you have to know how to do your part, and that only comes from solid training. But will you need to shoot that far? Probably not in most cases- and only your own situation can determine this. Most often our expectations should be half that distance at the most, but if everyone in your group can make those kinds of shots, then they’ll have no problems engaging closer than that.

Practical accuracy comes from the individual rifleman; riflemen are only produced and maintained through quality training. The tactics of the Team of Riflemen are the real difference maker. You should be seeking out training outside the square range on a regular basis. My friend JC Dodge has an upcoming class which will go beyond the typical comfort zone of most, pushing both the student and his equipment. In addition, I’m available for those seeking private instruction on both making the shot and proper field techniques, along with other small units skills such as Off-Grid Communications, Recon & Surveillance, Basic Survival and Combat Casualty Care. We’re not the only ones who can teach this stuff; there’s many others. But I highly implore the reader to get that training along with all the other skills to give you the tactical edge in setting up a secure retreat, even if you think you’re the ‘expert’. And with that, I’ll leave you with a quote from the late, great Peter Kokalis:

To train others in the art of war, you must both know war from the trenches and undergo constant training from others, both to keep the sharp edge and be exposed to the ever-evolving tactical concepts of combat at the down and dirty level. Several have asked why an “expert” (God how I loathe that word) like me would need to participate in training at a firearms school. The answer is simple: for the same reason tennis and golf pros constantly train under other tennis and golf pros. You cannot observe yourself while shooting, but the professional firearms instructors under whom I train can constantly detect slight nuances of incorrect movement that need to be reprogrammed.

You arrive at your favorite coffee shop in the ‘burbs and notice a guy in a green baseball cap standing behind you. You give him a friendly nod and go back to looking at the menu.

While you’re taking a bite from your Arby’s roast beef sandwich during your lunch break downtown, you notice that same guy in the green ball cap at a table outside. “Huh. Small world. What a coincidence,” you think to yourself.

Work is over, and you roll up to the gym to get your sweat on. While you’re walking to the entrance, you glance over and see Mr. Green Baseball Hat sitting in a car in the parking lot.

You get the sinking feeling that this third spotting isn’t a coincidence and that maybe this guy is following you.

What do you do?

Unless you’re a criminal or suspect in some crime, you probably think you don’t have to worry about being followed.

But even if you’re a law-abiding citizen, there’s a chance you could be followed at some point in your life by people who’d like to do you harm: an angry employee that you had to fire; a crazy ex; friends and family of said crazy ex; an unstable person you unintentionally offended at church; a weirdo you met once at a party who is now obsessed with you; the guy you accidentally cut off in traffic three miles back; a thief who’s decided you’re a good mark. The list goes on.

There’s also a chance you might be followed by a private investigator due to a divorce, custody battle, or other litigation you’re involved in. If that’s the case, you want to provide as little information to the PI as possible to avoid inadvertently giving your legal opponent fodder that somehow helps their case.

The chances of these kinds of people following you are slim. But if you do find yourself in this situation, it’s good to have a plan on what to do.

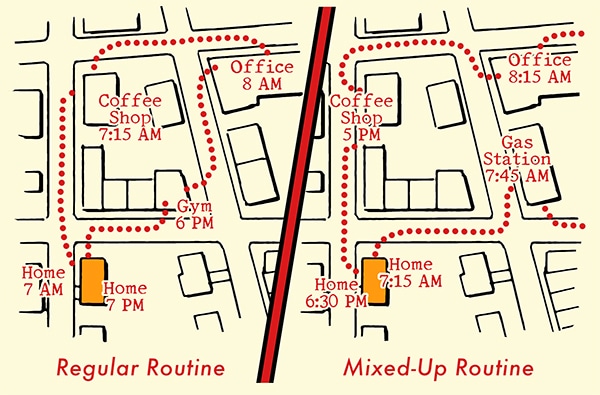

If you don’t want someone following you, the best thing to do is to make yourself less “followable” in the first place. Stalkers, PIs, or people who want to do you harm count on the fact that you have a set routine that they can easily follow along with. You subtract that advantage, and make yourself less of an easy target, by making your schedule less predictable. If you can, mix up how you get to work throughout the week. Don’t go to the same places on the same days and at the same times.

Also, don’t broadcast your whereabouts on social media. Turn off location services that indicate where you’re posting from. Would-be stalkers will check this info so they can pinpoint your movements.

You’d be surprised how easy it is to tail someone without them knowing, as most people aren’t paying attention to their surroundings. So the first step to figuring out if you’re being followed is to start keying in on what’s going on around you. Maintain situational awareness while you’re out and about and establish baselines. What’s normal for the situation or environment you’re in?

Once you’ve established baselines, pay attention to possible anomalies. Is someone looking at you more than is normal and making an unusual amount of eye contact? Does a car you don’t recognize keep driving by your house? Has someone been showing up to your favorite coffee shop who doesn’t fit the typical crowd? These are anomalies and should put you on the alert that someone might be following you.

One anomaly to register is seeing the same person, in three different places. Ex-CIA officer Jason Hanson gives this rule of thumb used in the intelligence community:

One time=an accident

Two times=a coincidence

Three times=enemy action

In addition to noting anomalies, pay attention to your gut feelings. You’ll often intuitively know when something is wrong.

Then, if you experience those uncomfortable feelings, try to confirm them. How you do so will differ as to whether you’re in a car or on foot.

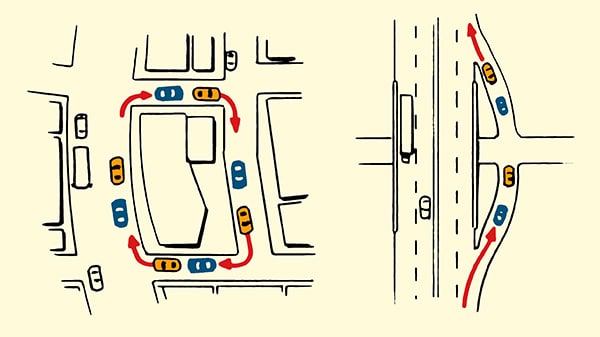

If you suspect someone is tailing you in a car, you can confirm it by doing the following:

1. If you’re on city streets, make four right turns. If the car is still behind you after the fourth turn, they’re probably following you. Most people don’t travel in circles around city blocks.

2. If you’re on the freeway, get off and then immediately get back on. If you can still see the car in your review mirror, you’re probably being followed. Just as most people don’t travel in circles on city streets, most people don’t get off and then right back on a freeway.

You can also get over to the right lane of the highway, and slow down to 15 miles or so below the speed limit. All the cars behind you will soon pass by. If the one you’ve had your eye on doesn’t, it’s almost assuredly following you.

1. Mix up your routine. If you’ve got a daily routine, you likely see the same people at the same time at the same places. For example, if you go to the gym every day at 6 PM, you’re probably going to see the same people there. Thus, it’s hard to tell if someone you always see some place is following you, or just has a similar routine to yours.

So if you suspect someone has been following you, you can further confirm it by mixing up your routine. Instead of going to the coffee shop at 7 AM like you usually do, go to a convenience store. If you see your potential pursuant at the convenience store too, there’s a good chance they’re following you. You can increase your certainty of being followed by going to different places at different times. If you see the same person no matter the time and no matter the place, you can be pretty sure they’re following you.

2. Mix up your walking pace. If someone is tracking you, he’ll likely match your walking pace. If you speed up, he’ll speed up. If you slow down, he’ll slow down. If you pause, he’ll pause. So mix up your pace and observe how your suspected stalker responds. If he matches your pace, there’s a good chance he’s following you.

3. Pause and turn. Hanson suggests this effective tactic for determining if someone is following you:

“While you are walking, simply pause, turn around, and pretend to do something — like check your phone, tie a shoe, or turn around as if you were looking for someone. Then look directly at the person you think is following you. Your typical amateur who is following you is going to get flustered and give herself away. She’s likely to freeze or act unnatural because you have caught her by surprise. In other words, someone who is following you will not exhibit the same natural behavior as someone who is simply walking down the street.”

4. Change direction. As you’re walking, stop and turn around 180 degrees and start walking towards the person you suspect is following you (only do this in a public and crowded space). If your suspected stalker also flips around and starts walking behind you again, you can confirm that you’re being tailed.

So you’ve confirmed that you’re being followed. Now what? If possible, you want to avoid a confrontation, which all self-defense experts agree is better than needlessly getting into a violent encounter.

To do this, follow these two general rules, as well as guidelines that pertain specifically to whether you’re driving or on foot.

Rule #1: Don’t go home. Whether you’re walking or driving, don’t go to your house. It’s natural to want to get home and lock the doors, but if your tail doesn’t know where you live, you don’t want to reveal that information by taking him there.

Rule #2: Stay in public, well-lit, and well-populated areas. Don’t go anywhere that will put you by yourself with your pursuant. If you’re in your car, stay on main roads that are well-lit and don’t go down country roads or secluded streets. If you’re on foot, stay in public areas where there are lots of people. You don’t want to go down isolated alleyways where you can be cornered. If someone seems to be following you in a store, you also don’t want to go out to your car; the stalker could ambush you in the parking lot or follow you home.

Gather info. If you’ve confirmed you’re being followed in your car, start getting information on the tailing vehicle to potentially look into yourself or pass along to the police. Get the vehicle’s make and model. And if you can score the license plate number, even better.

Call the police. If you feel threatened, call the police to let them know what’s going on. Or simply drive to your local police precinct, and tell them you believe you’re being followed. Give an officer the information on the car that’s following you and let them take it from there.

Use well-trafficked roads with lots of stoplights and stop signs. Your pursuant might get stuck at a light or behind more traffic, giving you the chance to shake him off.

Be ready for evasive maneuvering. While on the roads and at stoplights, maintain enough distance between you and the car in front of you that you can make an escape maneuver if needed. If you can see the tires of the car in front of you, you’re good.

Only return home once you feel sure you’re no longer being followed by your tail.

Call the police. If you believe you’re being followed on foot by someone with ill intentions, call the police and give them a description of your pursuant. Keep the police on the phone for as long as possible. If your pursuant is nearby, talk loudly so he or she can hear what you’re saying. If there’s a police precinct nearby, go to it.

Use public transportation to shake your tail. If you know the public transportation departure times, you can hop on a bus or subway at the very last minute to lose whoever’s following you.

Acknowledge your follower. One tactic Hanson recommends using in public areas is to simply let your follower know that you know they’re following you. Turn around and look right at them. If you’re feeling brave, ask “Can I help you?” Or “What do you want?”

Most bad guys are criminals of opportunity. They’ll only go after you if they think you’re a “soft target” — that they have some sort of tactical advantage over you. Following you without you knowing is one such advantage. By acknowledging their presence, you take it away. Once they realize you’re alert to their tail and they’ve been spotted, they’ll often get flustered and immediately disengage. You’d be surprised how often a show of assertiveness will cause a would-be criminal to back down (at least if their behavior is of the social aggression rather than asocial type; if the latter, you should be prepared to fight back).

Again, you generally only want to use this tactic if you’re in a well-lit and well-populated area, in case the stalker advances instead of retreats. You want witnesses.

If for some reason you find yourself in an international, high-stakes espionage manhunt like Jason Bourne, the tactics above aren’t going to work. In fact, you’re pretty much hosed. First, it’s going to be very difficult to even determine that you’re being followed. Highly skilled, professional trackers will use teams of people to co-ordinate surveillance on you. Instead of a single person following you everywhere you go, they’ll throw you off by having one person follow you in one area and another person follow you when you arrive somewhere else. They can even swap those people out to avoid you getting suspicious.

Even if you do figure out you’re being followed, because professional investigators work as a team, it’s hard to shake them. You might be able to delay their finding you, but they’ll almost assuredly get you in the end.

Long story short: try not to get into a Jason Bourne-style manhunt.

But if you’re being pursued by a more garden-variety stalker, the tips above will help.

Last updated: October 9, 2017

In any survival scenario, water is by far your most important resource. You can easily go a day without food, and usually don’t need shelter right away, unless you’re in freezing conditions. Not having any water for 24 hours, however, while survivable, depletes both your physical and mental strength, making it more difficult to perform the tasks necessary to making it out the other side. And after just three days without hydration, your body will shut down, and it’ll be lights out for you.

With about two liters per day your body will be able circulate blood, process food, regulate body temperature (which prevents hypo- and hyperthermia), think clearly, and successfully carry out a host of other internal processes.

You can see how crucial water is to your survival. Luckily, with just a little bit of know-how, water can be found relatively easy in almost any environment on the planet. In today’s article, we’ll walk you through several methods for finding water that will work for temperate climates and a variety of others, as well as methods that are particularly suited for tropical, freezing, and desert regions.

Any survival expert will tell you that no matter where you find water in the wild — be it from streams, lakes, condensation on plants, etc. — it should always be filtered or purified before drinking. Now, in many cases this isn’t possible, as you may not have the right supplies on you. Just know that any water you ingest without purifying could carry harmful bacteria, and is a risk on your part. If your choice is life or death, that’s a risk you’re most definitely going to take. Some water collection methods are safer for straight drinking than others; we’ll outline those below.

The following tips work especially well in temperate and tropical areas, but many also apply to other climates too.

These are your most obvious sources of water in the wild. Clear, flowing water is your best option, as the movement doesn’t allow bacteria to fester. This means that small streams should be what you look for first. Rivers are acceptable, but larger ones often have a lot of pollution from upstream. Lakes and ponds are okay, but they’re stagnant, meaning there’s an increased chance for bacteria.

Now then, how do you go about finding these bodies of water? First, use your senses. If you stand perfectly still and listen intently, you may be able to hear running water, even if it’s a great distance away.

Next you’ll use your eyes to try and find animal tracks, which could lead to water. Insect swarms, while annoying, are another sign of water close by. And in the mornings and evenings especially, following the flight path of birds may lead you to your much-needed H2O. Watching animal behavior is especially important in the desert. Animal tracks will be easier to spot in the sand, and they’ll almost always eventually lead to water. Birds will also especially flock towards water in dry areas.

Also just scout the environment you’re in. Water runs downhill, so follow valleys, ditches, gullies, etc. Find your way to low ground, and you’ll often run into water.

Collecting and drinking rainwater is one of the safest ways to get hydrated without the risk of bacterial infection. This is especially true in wild, rural areas (in urban centers, the rain first travels through pollution, emissions, etc.).

There are two primary methods of collecting rainwater. The first is to use any and all containers you might have on you. The second is to tie the corners of a poncho or tarp around trees a few feet off the ground, place a small rock in the center to create a depression, and let the water collect.

You can combine these methods and make your containers more effective by tying the poncho or tarp to funnel into your bottle or pot or whatever you have (as long as it doesn’t overflow and waste water!).

Looking for a way to collect up to a liter of water per hour? Tie some absorbent clothes/cloths or tufts of fine grass around your ankles, and take a pre-sunrise walk through tall grass, meadows, etc. Wring out the water when the cloths are saturated, and repeat. Just be sure you aren’t collecting dew from any poisonous plants.

Fruits, vegetables, cacti, fleshy/pulpy plants, even roots contain a lot of water. With any of these, you can simply collect the plants, place them into some kind of container, and smash them into a pulp with a rock to collect their liquid. It won’t be much, but in desperate situations, every little bit helps.

This method is especially helpful in tropical environments where fruits and vegetation are abundant. Coconuts can be an excellent source of hydration. Unripe, green coconuts are actually better, though, as the milk of ripe coconuts acts as a laxative, which will just further dehydrate you.

Another easy option for water collection is taking advantage of plant transpiration. This is the process in which moisture is carried from a plant’s roots, to the underside of its leaves. From there, it vaporizes into the atmosphere; but, you’re going to catch the water before it does that.

First thing in the morning, tie a bag (or something you can make into a bag; the larger the better) around a leafy green tree branch or shrub. Place a rock in the bag to weigh it down a little bit so the water has a place to collect. Over the course of the day, the plant transpires, and produces moisture. Rather than vaporizing into the atmosphere, though, it collects at the bottom of your bag. Never do this with a poisonous plant.

Like with fruits/vegetation, this is another source that won’t provide all that much water, but again, it’s definitely something when the straits are dire – particularly when you’re stranded in a desert. The crotches of tree limbs, or the crevices of rocks can be small collecting places for water. In an arid area, bird droppings around a rock crevice may indicate the presence of water inside, even if it can’t be seen. To remove water from crotches and cracks, stick a piece of clothing or cloth in, let it soak up any moisture, and wring it out. Repeat if you can, and return after a rain for a fresh supply.

The benefit of creating a still is that it provides a reliable, fairly substantial source of water (compared to other methods), and you know roughly how much you’ll be getting, which helps you plan and ration better.

There are aboveground and underground varieties of sills; the underground is your best bet as it collects more water, but the aboveground variety can be useful if you’re extremely energy-depleted and can’t dig a large hole. Click here to see instructions for doing that (page 58).

Directions for your underground still:

Supplies

Instructions

There’s almost always moisture in the ground at that depth. That will react with the sun’s heat to produce condensation, which will collect on the plastic. The inverted cone forces that condensation down into your container. You can expect to gather .5-1 liter per day, so you’d need more than one (or another source) to account for an entire day’s supply.

Especially in the mountains, snow and ice are abundant well into the summer months, and sometimes all year round. If you’re by or on the ocean in a polar region, look to icebergs for a source of fresh water and for “old ice” that has been through rains and thaws. As opposed to salty ice, which is opaque and gray, freshwater ice has a bluish color and crystalline structure, and splinters easily with a knife.

If you’re in a boat and surrounded by salt water, capture some in a container, and allow it to freeze. The fresh water will freeze first, while the salt will accumulate as slush in the middle. Remove the ice and discard the slush.

While snow and ice provide an excellent source of water, it should always be melted and purified first. Eating straight snow/ice will lower your body temperature, which dehydrates you because it forces your metabolic rate to speed up in order to keep you warm.

The best way to melt snow/ice and make it actually taste good is to simply mix it with other water you may have, even small amounts, and slosh it around until the snow melts. If you are heating it, add a little bit of other water to it; heating snow/ice directly can actually scorch it and produce a foul-tasting drink.

In temperate, tropical, and frozen/icy climes, finding and collecting water is likely to happen within your 3-day window. Your primary concern is going to be collecting, storing, and purifying it. In desert environments though, simply finding a water source can be enormously difficult. Here a few tips specifically for arid environs:

Start digging. Anywhere you see dampness on the ground or green vegetation, dig a large hole a few feet deep, and you’ll likely get water seeping in. The same is true at the feet of cliffs, in dry river beds, at the first depression behind the first sand dune of dry desert lakes, and in valleys/low areas. You may not be successful, but you just might. This water will of course be rather muddy, so it will especially need filtering/purifying, but you’ll have a water source nonetheless.

Extreme temperature variations between night and day can cause condensation on metal surfaces. Before the sun rises and vaporizes that moisture, collect it with absorbent cloth. This also means you should be placing your metal items in the open rather than stored in your pack.

If you’re stranded on land near a body of saltwater, you can still attain fresh water by digging a well on the beach. Behind the first sand dune — typically about 100 feet from shore — dig a 3-5’ hole. Line the bottom with rocks, and the sides with wood (driftwood, most likely). This allows the well to fill up without collapsing or having too much sand in the water. In a few hours, you’ll have a well full of fresh water — a combination of collected rainwater (which runs down the dunes), and sand-filtered ocean water. If it tastes salty, you simply move a little further away from shore.

A variation of this method is to let the water seep in, but then heat some additional rocks and drop them in the water. This will create steam, which can be collected by holding an absorbent cloth over the well. Wring out the cloth and repeat. This ensures that your water is free of all salt and other contaminants, but you will yield less.

In any desperate survival scenario, you may be tempted to try non-water liquids as a substitute for the real thing. In all but the most dire of situations, these should be avoided. In general, non-water substitutes only worsen your heath and vigor. These substitutes, and their harmful characteristics below:

Of course, if you’re a Bear Grylls fan, you’ll know he famously drank his own urine while in the Sahara Desert. Is this safe to do, or was that for entertainment purposes? If you’re down to your very last resort, drinking your urine can keep you alive for another day or two. It’s 95% water, but that other 5% is comprised of waste products that will ultimately lead to kidney failure if subsisted on for more than a very short period of time. And of course as you get more dehydrated, this method becomes even more dangerous.

Before you resort to drinking your own pee, exhaust all the methods outlined above first. With a little effort, knowledge, and ingenuity, there’s a good chance you’ll be able to find genuine H2O.

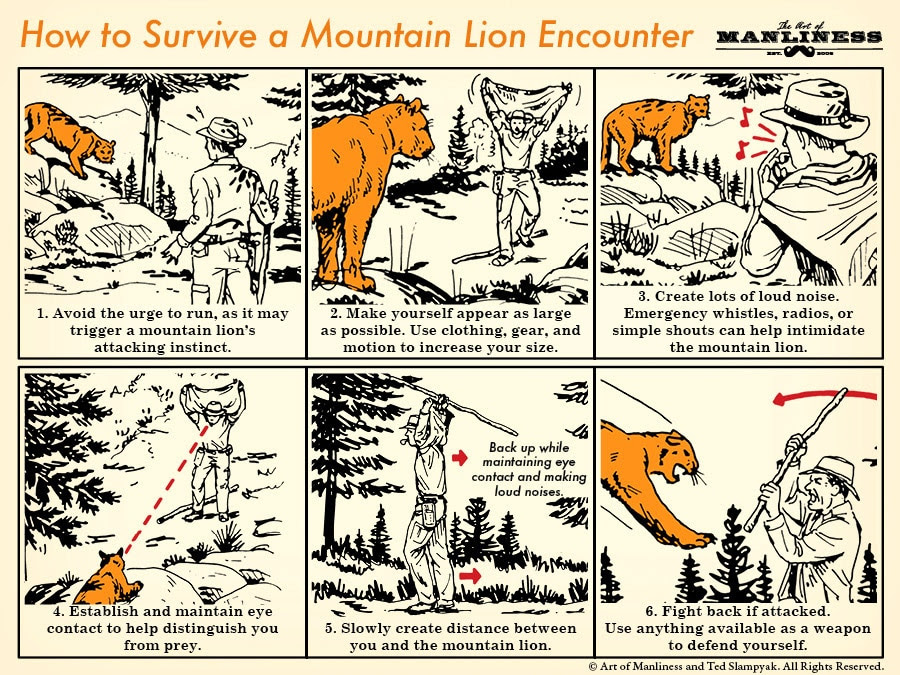

Spotting large predators in the wild is a thrill for any hiker or outdoorsmen, but coming face-to-face with a 220-pound cat can turn a walk in the woods into a fight for your life. Also known as cougars in some parts of the country, mountain lions tend to attack when cornered, or when they believe you might be a reasonable piece of prey. The key to avoiding a deadly encounter on the trail starts with a calm reaction.

Like this illustrated guide? Then you’re going to love our book The Illustrated Art of Manliness! Pick up a copy on Amazon.

Illustrated by Ted Slampyak

When I first dipped my toes into precision rifle competition the very first match that I attended did not allow competitors to use laser rangefinders to get distances to the target. This was familiar territory for me since I’d been trained in range estimation using the reticle in the Leupold M3A and Steiner binos. Getting an accurate range estimation using just a reticle requires a good deal of skill and prior information though, such as the dimensions of the target. If you didn’t know the dimensions of the target you were in a bit of a pickle but laser rangefinders don’t suffer that disadvantage. Although you don’t have to know the size of the target to get a range, using a laser rangefinder isn’t always as easy as point and click. Laser rangefinders were once expensive luxuries but the newer models are smaller, range farther, and pack more features than the models from just a decade ago. However, it’s a good idea to research the options that are out there now to make sure that your money is well spent and that the unit will meet your needs.

New laser rangefinders pack in a lot of bang for the buck. The Leica 1200 CRF at the top was good for its day but newer models like the Sig KILO below provide the ability to range farther, range in meters or yards, account for angles, and adjust the brightness of the display

In simple terms, the laser rangefinder will emit an infrared beam towards a target while another sensor looks for the reflection coming back. Once the sensor has detected that reflection it calculates the range based on the time it took to get back to the unit and displays it for the user. Current generations of rangefinders can not only do that in less than a second but also provide the angle to the target by way of an internal inclinometer as well as differentiate between clutter and the actual target. The rangefinders that have a “brush” mode accomplish this by programming the rangefinder to essentially ignore close readings and display the farthest distance. This is especially helpful for long range hunters that may have to punch through scrubs or foliage in order to get a reading on an animal. Nearly all of the off-the-shelf rangefinders work the same way so what sets a $300 rangefinder apart from a $3,000 one?

In the world of electronic devices, you tend to get what you pay for and laser rangefinders are no different. One area that sets apart good laser rangefinders from great ones is the quality of their sensor and emitter package. You may find that rangefinders at the lower end of the pricing spectrum use an emitter with a less focused beam coupled with a sensor that isn’t as sensitive to the reflected signal. The result is a rangefinder that can maybe do 800 yards off of a reflective target in perfect conditions as opposed to 1000+ yards. More expensive laser rangefinders with a higher maximum distance rating will use an emitter that has a tighter beam divergence in addition to a sensor that is better able to pick up the reflection off a variety of materials.

If you notice that some rangefinders use a Class 1 laser and some use a Class 3R laser I wouldn’t get too wrapped around the axle about it. Class 1 lasers are more or less eye safe while Class 3R lasers are less so but still ok around humans as long as you take precautions. The laser classification doesn’t necessarily mean that a rangefinder with one type is going to be better than the other one. Again, the overall performance is going to be determined by the focus of the beam and the quality of the sensor used to pick up the return.

The optical performance of the rangefinder is going to play a part in how well you can range objects, mostly in how well you can see the target. All laser rangefinders have some level of magnification, most of the monocle rangefinders have 7X but sometimes you’ll see 6X and 8X too. I like the 7X magnification, it offers a good balance between being able to see targets against brush or in shadows while still having a good field of view. Some of the binocular laser rangefinders will have a higher magnification, typically 10X or so, which is just about perfect for hunting situations where you may have to look through brush or scan a far hillside.

Going hand in hand with the magnification of the unit is the quality of the glass. I try not to be a glass snob but it really can make all the difference in a laser rangefinder. I’ve used laser rangefinders before where the image looking through the unit was so dark it almost seemed like you were wearing sunglasses. Now most rangefinders do have a coating on the lens to help you see the display inside but you’ll want a laser rangefinder with good glass quality. Good enough that you can spot a gray, shot up piece of steel against a far hill while it’s sitting in the shadows of the brush. That might sound a little far-fetched but that very scenario occurs at nearly every match I’ve been to.

I mentioned it a little bit earlier but when I was talking about the focusing of the laser I was talking about beam divergence. Laser beams do not stay as focused points of light forever and ever. If you take a laser pointer and aim it a close object you’ll probably see a nice point of light there. Now, aim that same laser at a far wall and you’re likely to see an oblong patch of light instead of that defined point. The beam from the laser pointer spreads out and the same thing happens to the beam in a laser rangefinder, this is called beam divergence. The manufacturer can focus the beam in different dimensions to suit the overall requirements of the laser rangefinder. Ideally, you want the tightest beam divergence that you can get, since too wide of a divergence can cause the unit to provide false readings. The beam divergence in my Leica 1200 CRF is .5 X 2.5 mils, which translates to 1′-6″ X 7′-6″ at 1,000 yards. That’s not too bad as rangefinders go, I can still range trees at over 1,000 yards, but my Leica is over a decade old, many of the newer models have a much tighter beam divergence for better ranging.

I used my Leica 1200 CRF to range a piece of farm equipment more than 130 yards beyond it’s stated maximum range. The combination of high quality emitter and sensor along with ideal lighting conditions helped push the boundaries of this compact laser rangefinder. The beam divergence at this range is approximately 2′-0″ X 10′ – 0″, luckily the farm equipment was huge.

We’ve talked about the aspects of a laser rangefinder that help explain how it provides the range, now let’s talk about some of the things it should do. When you’re out looking for a new rangefinder my first piece of advice is to start looking for one that has a maximum distance rating 20-30% more than what you think you need. If you get a unit that will range farther than you need it to, you can count on it to be able to hit those targets you need to get a range on in less than perfect conditions. The rangefinder should also be able to give you the slope distance to the target, which is extremely important for a rifleman that’s shooting in steep terrain. Whether you’re shooting uphill or downhill the actual distance the bullet is affected by gravity is less than the gun-to-target distance because gravity is pulling straight down. Knowing this slope distance is very important when shooting at steep angles because just using the gun to target distance could result in a miss. Integral ballistic computers are also becoming more and more common with laser rangefinders, something precision rifleman and hunters alike can appreciate. Some units only display relatively generic ballistic information while others can offer custom gun profiles. Probably one of the best full-featured rangefinders on the market is the Sig KILO2400ABS, a compact laser rangefinder with a built-in Applied Ballistics computer.

The Sig KILO can range to the 1/10th yard and automatically provides the adjusted range for slope when in AMR mode. This takes the guesswork out of adjusting the range for high angle shots.

Laser rangefinders can be hamstrung but a number of factors that can dramatically reduce their range and effectiveness. Ambient lighting conditions can be the Achilles Heel of a rangefinder, with bright sunny days being the worst for trying to max out a laser rangefinder. On really bright sunny days I’ve had my Leica 1200 CRF, which I know can range past 1,200 yards, fail to range anything past 900 yards. In my experience, ideal conditions for a rangefinder are when the light is more diffused such as on overcast days or in the evening as the sun is going down.

Overcast lighting conditions such as this are ideal for laser rangefinders if you want hit the limits of their ranging ability. Bright, sunny conditions can reduce the effective range of some laser rangefinders by 30%.

Additionally, things like the orientation, color, and size of the target can all play into how well you’ll get a reading at distance. A laser rangefinder works best when hitting a flat surface since it gives it the best chance of reflecting back a good signal. If the target is angled away this can increase the chances of the sensor not picking up the beam. Likewise, dark colors also do not do particularly well when trying to reflect a beam back to the unit, lighter colors work best in this regard. I think it also goes without saying that trying to range small objects that are far away can also be challenging so try to pick large objects with lightly colored flat sides if you can.

To get the most out of your rangefinder here are some things that you can do to help get an accurate distance reading.

Using a tripod is the best way to get accurate long range readings with a laser rangefinder, especially if the target is small. Some rangefinders have a built-in 1/4-20 attachment point, however, in some cases you may have to use a secondary mount. This universal optics mount from Precision Rifle Solutions is an excellent way to mount laser rangefinders for a steady hold on a long-range target.

As you may have guessed by now laser rangefinders are an incredibly effective tool for long range shooting, but they are not miracle workers. That being said if you are going to get a laser rangefinder to fill out your long-range kit then spend as much as you can, buy once cry once applies here. When I bought my Leica 1200 CRF over ten years it was one of the best compact rangefinders you could get and pricey. Now, after a decade of use, it’s a little worse for wear but it works great and still ranges to beyond it’s stated limit so the cost is justified.

For some great laser rangefinder options check out the table below.

| Laser Rangefinder Guide | ||||

| Manufacturer | Range | Angle Compensation | Multi-Mode | Ballistics |

| Bushnell Elite 1 Mile ARC | 5-1760 yards | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bushnell Fusion 1 Mile ARC Binoculars | 5-1760 yards | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Leica Rangemaster 2700-B | 10-2700 yards | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Leupold RX-1300i | 6-1300 yards | Yes | Yes | No |

| Sig KILO2200MR | 3400 yards | Yes | Yes | No |

| Sig KILO2400 ABS | 3400 yards | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Vortex Ranger 1500 | 9-1500 yards | Yes | Yes | No |

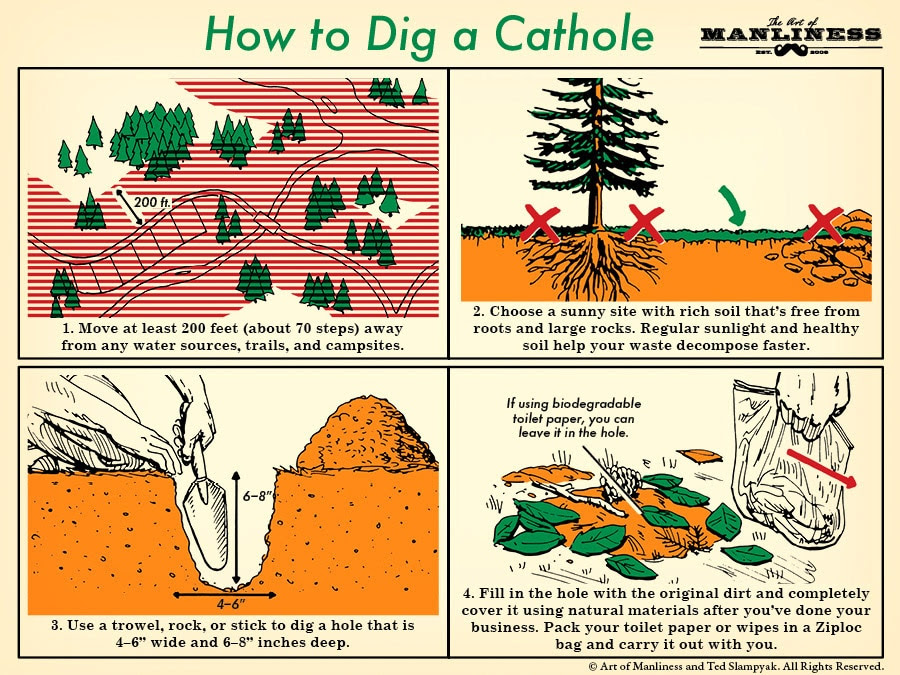

When nature calls and you’re in its house, no toilets are going to spring up out of the ground ready to use. A good outdoorsman knows to dispose of their waste properly, using Leave No Trace ethics to dig a cathole in an appropriate location. Properly executed, a cathole ensures that your business decomposes quickly so your favorite trails and outdoor havens stay clean and tidy.

Like this illustrated guide? Then you’re going to love our book The Illustrated Art of Manliness! Pick up a copy on Amazon.

Illustration by Ted Slampyak

| January 11, 2016

“It is hard to over-value the powers of the clever tracker. To him the trail of each animal is not a mere series of similar footprints; it is an accurate account of the creature’s life, habit, changing whims, and emotions during the portion of life whose record is in view.” –Ernest Thompson Seton, Boy Scout Handbook, 1911

The other day while hiking some muddy trails with my family, my son pointed to a set of tracks and asked me what animal had made them. “That’s easy,” I said, “those are the tracks of a whitetail deer.” “What about those?” he asked, pointing to another set of footprints. “Those are, um, hmmm, well, I’m not sure what they are,” I confessed. I realized I needed to brush up on my knowledge of animal tracks.

Learning how to track and identify the footprints of animals is an ancient and largely forgotten art — one that’s not only important for hunters, but also enhances any outdoorsman’s experience in the wild. It’s fascinating to know what creatures are sharing the woods with you, and trying to track them down by following their trail is a lot of fun. Learning how to read tracks allows you to pick up on the little dramas enacted by wildlife that usually go unnoticed by the human eye. It’s thus a skill that both deepens your understanding of nature and heightens your all-important powers of observation.

Becoming an expert tracker takes years of practice. To get you started, today we offer a primer on the basics of identifying the footprints of common animals. We’ve taken as our guides two master woodsmen of yore — Ernest Thompson Seton, one of the founders of the Boy Scouts, and Charles “Ohiyesa” Eastman, who was raised as a Sioux tribesman — as well as drawn on tips from Tom Brown Jr., one of the foremost modern trackers.

Let’s head into the woods and see what we can discover!

“Never lose the chance of the first snow if you wish to become a trailer.” –Ernest Thompson Seton

Winter is primetime for animal tracking, as the prints are easy to find in the snow and can be followed for a long distance. However, as Seton explains:

“the first morning after a night’s snow fall is not so good as the second. Most creatures ‘lie up’ during the storm; the snow hides the tracks of those that do go forth; and some actually go into a ‘cold sleep’ for a day or two after a heavy downfall. But a calm, mild night following a storm is sure to offer abundant and ideal opportunity for beginning the study of the trail.”

The drawback of snow tracking is that in deep, soft snow you may find only the holes made by the animal’s feet and legs. Further accumulation and melting can also easily obscure the trail. And of course, some animals don’t come out at all during the winter because they are hibernating.

For these reasons, mud and fine, wet sand can be an even better medium, as they hold the shape of the footprint well. A mudbank stream is one of the best places to look for tracks, as it’s frequented by shore birds and waterfowl as well as animals like the raccoon and muskrat looking for food. After a rain, sand bars, ditches, and muddy gullies are also fruitful places to find the tracks of deer, possums, and other creatures. Looking over a dewy, open field in the morning can reveal the tracks creatures made in the night as well.

Whether in snow or dirt, a track is best and easiest to follow when it is freshest — before wind, rain, melting (in the case of snow), and debris have obscured the prints.

While it’s surely fun to track animals through the wilderness, it’s also enjoyable to try to find their footprints in your very own backyard (and around the trashcan!). So always be aware of your surroundings wherever you go, and you never know what you’ll see.

In learning which tracks belong to which animals, it can help to know the basic classifications of common animal families. Simply by counting the number of toes in a footprint, you can figure out which family the creature belongs to, and from there work on narrowing down which species you’re looking at.

In this narrowing down process, it’s useful to know which animals are common to your area. As Seton explains, “In studying trails one must always keep probabilities in mind”:

“Sometimes one kind of track looks much like another; then the question is, ‘Which is the likeliest in this place.’

If I saw a jaguar track in India, I should know it was made by a leopard. If I found a leopard in Colorado, I should be sure I had found the mark of a cougar or mountain lion. A wolf track on Broadway would doubtless be the doing of a very large dog, and a St. Bernard’s footmark in the Rockies, twenty miles from anywhere, would most likely turn out to be the happen-so imprint of a gray wolf’s foot. To be sure of the marks, then, one should know all the animals that belong to the neighborhood.”

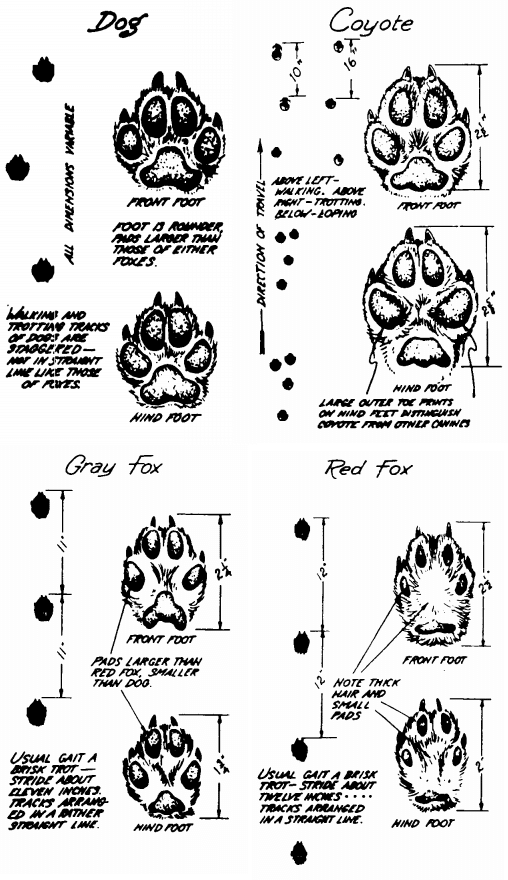

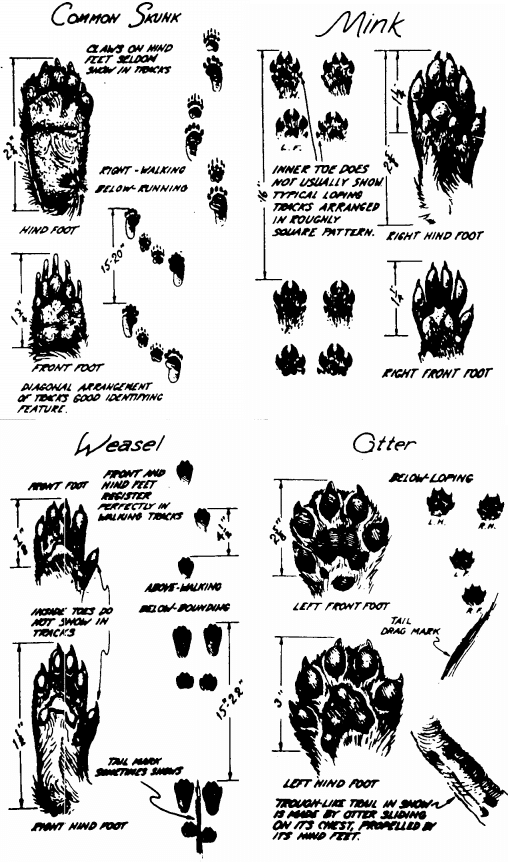

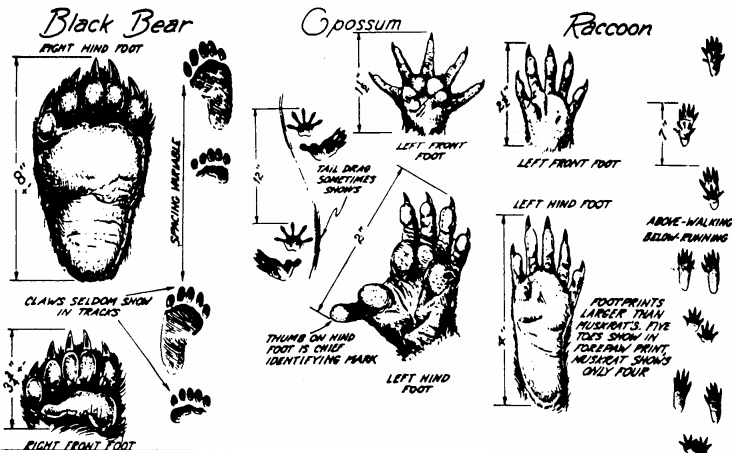

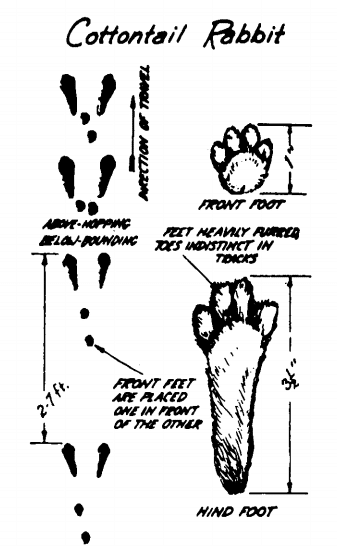

Below you’ll find illustrations of the footprints of the track classifications for the most common families of animals; they break down not only what the tracks look like when the animal is walking (which is its typical gait), but also hopping/running (which it may do when chased by a predator, or doing some chasing of its own).

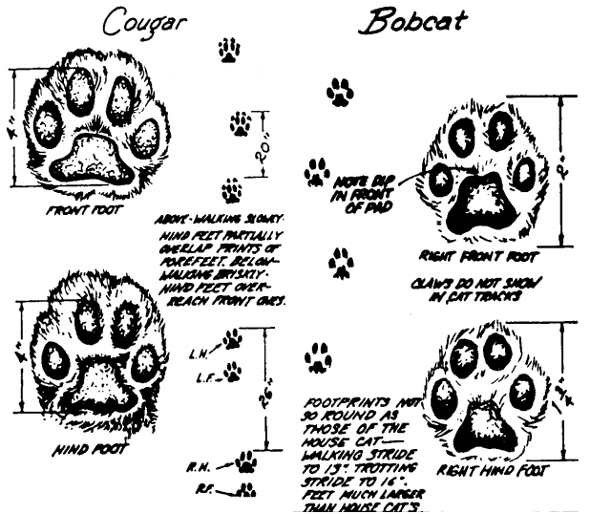

Cats leave rounded prints that show four soft, pliable, spread toes. The prints lack claws, since they’re retractable. A cat also walks in what’s called a “single register” — its hind legs exactly track its front legs, so that it appears to only be walking with two legs, rather than four. This aids in quiet, stealthy stalking.

Canines have four toes like cats, but their feet are harder and their claws can be seen as they don’t retract. While the fox walks in a single register, dogs and coyotes walk in an indirect register — their hind legs land a little behind and to the side of the front print, leaving a messier track than that of a cat.

Members of the weasel family have five toes on both their front and hind feet, though all five don’t always show in the track.

While bears, possums, and beavers don’t belong to the weasel family, their tracks are similar in that they also have five toes in both back and front. However, they differ in the flat, human-like nature of their feet.

Rabbits have four toes on both their front and rear feet, and in almost all species the back feet leave tracks that are at least twice the size of the front.

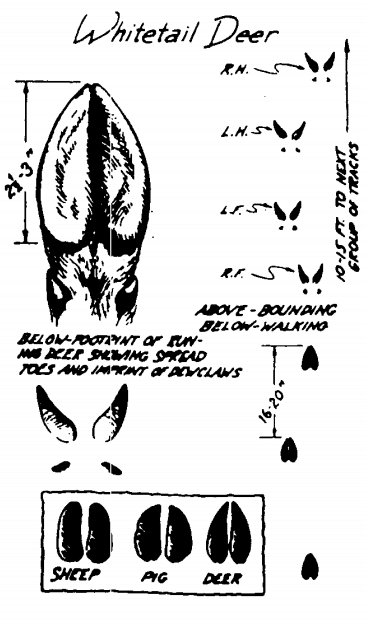

The tracks of hoofed animals are easy to recognize, and deer tracks are some of the most common to find in the woods. You can distinguish a doe from a buck, in that the female has sharper hoofs and a narrower foot than the male.

“I will now ask you to enter the forest with me. First, scan the horizon and look deep into the blue vault above you, to adjust your nerves and the muscles of your eye, just as you do other muscles by stretching them. There is still another point. You have spread a blank upon the retina, and you have cleared the decks of your mind, your soul, for action.

It is a crisp winter morning, and upon the glistening fresh snow we see everywhere the story of the early hours — now clear and plain, now tangled and illegible — where every traveler has left his mark upon the clean, white surface for you to decipher.

The first question is: Who is he? The second: Where is he now? Around these two points you must proceed to construct your story.” –Charles Eastman (Ohiyesa), Indian Scout Talks, 1915

Now that you know what the tracks look like, how do you follow the trail once you’ve identified it?

When following an animal’s footprints, try to track towards the sun if possible, as the shadows will make the impressions stand out more. The sun’s position in the sky during the early morning and late afternoon will particularly enhance the tracks.

As you follow an animal’s tracks, don’t just focus on the discrete sets of prints themselves, but continually take in the trail as a whole — which may in fact be easier than finding individual footprints. For example, by looking ahead, instead of having your nose to the ground, you may see a trail of bent grass through a field. Also look for other disturbances like cracked twigs, or pebbles and leaves that have been overturned to reveal their darker, wetter undersides. If you lose the trail, place a stick by the last set of prints you discovered and then walk around it in an ever widening spiral until you pick up the trail again.

Eastman lays out other considerations for your hunt:

“It is essential to estimate as closely as you can how much of a journey you will undertake if you determine to follow a particular trail. Many factors enter into this. When you come upon the trail, you must if possible ascertain when it was made. Examine the outline; if that is undisturbed, and the loose snow left on the surface has not yet settled, the track is very fresh, as even an inexperienced eye can tell…It will also be necessary to consider the time of year. It is of no use to follow a buck when he starts out on his travels in the autumn, and with the moose or elk it is the same.”

Animal tracks are the alphabet of the wild — an education in their language can help you read more of the nature all around you. As Seton concludes, knowing this language opens books of the woods and its inhabitants that would otherwise be closed to you:

“There is yet another feature of trail study that gives it exceptional value — it is an account of the creature pursuing its ordinary life. If you succeeded in getting a glimpse of a fox or a hare in the woods, the chances are a hundred to one that it was aware of your presence first. They are much cleverer than we are at this sort of thing, and if they do not actually sight or sense us, they observe, and are warned by the action of some other creature that did sense us, and so cease their occupations to steal away or hide. But the snow story will tell of the life that the animal ordinarily leads — its method of searching for food, its kind of food, the help it gets from its friends, or sometimes from its rivals — and thus offers an insight into its home ways that is scarcely to be attained in any other way.

The trailer has the key to a new storehouse of nature’s secrets, another of the Sybilline books is opened to his view; his fairy godmother has indeed conferred on him a wonderful gift in opening his eyes to the foot-writing of the trail. It is like giving sight to the blind man, like the rolling away of fogs from a mountain view, and the trailer comes closer than others to the heart of the woods.

Dowered with a precious power is he,

He drinks where others sipped,

And wild things write their lives for him

In endless manuscript.”

As an outdoorsman, I enjoy being afield in all sorts of capacities. While hunting is one of my favorite pastimes, fishing and hiking are a wonderful means of spending time with friends and family and living in close proximity to both the Catskill and Adirondack mountains, there is ample opportunity for both of those activities.

I am also, by trade, a Professional Land Surveyor, so my work hours are often spent in the remote wilderness areas. Here in Upstate New York we have a very healthy black bear population, and highway sightings are quickly becoming a regular occurrence, as are the classic raids on bird feeders and garbage cans alike.

When I head afield, I nearly always carry one form of sidearm or another, and while the truly dangerous encounters are definitely a rarity, I feel better knowing I can protect my loved ones and coworkers should the event unfold.

Now, the black bear is – generally speaking – a rather docile creature, and most of the time it will make every attempt to run away from man.

However, should you have the misfortune of getting between a sow and her cubs, or perhaps meet a cantankerous old boar, the black bear certainly has the equipment to rearrange your anatomy, and even possibly render your birth certificate null and void.

I’ve been privileged enough to take a couple of black bears – in both Quebec and New York – and have seen many more while at work and play.

His cousin, the brown bear, is an entirely different story; when a brown bear means business you need to stop the threat and stop it fast, by any means necessary.

Personally, I’ve only seen a grizzly bear from the comfortable confines of a vehicle, but that boar in Yellowstone Park made a lasting impression. I have yet to set foot in Alaska, but I have many friends and colleagues who either live there, or have significant hunting experience in the 49th state, where encounters with brown bears can honestly represent the hunter becoming the hunted.

With respect to the brownies, I have reached out to the bear guides, residents and hunters for their wisdom and experience on the matter, to find out exactly which sidearms they favor and why.

The author’s well-worn, and well-loved Ruger Blackhawk in .45 Colt is a perfect handgun for bear country.

Now before we take a look at particular models and calibers, let’s get one basic premise out of the way: when the excrement hits the oscillator, any gun is better than no gun. Personally, I do my best to avoid any encounter that could turn ugly, but that’s not always the case.

I remember clearly, back in 2002, while surveying in the foothills of the Berkshires a young employee came running up from the point he was supposed to locate, toward the survey instrument I was running.

His eyes were as wide as saucers, and he was taking strides twice as long as his normal gait would produce. “Phil, I can’t locate that corner; there’s a ****** bear down there!” Now, as surveyors, we carry machetes to cut the brush in between our survey stations, and we are rather proficient with them.

However, the realization that you might have to use one to defend against a couple-hundred pounds of teeth and fangs doesn’t exactly make one feel like Zorro; in fact, I looked down at it and said to myself: This is gonna hurt. I’d have gladly traded it for a snub-nose .38 Special.

This was a glaring example of surprise; this area, while remote, rugged and wooded, wasn’t known for its bear population, very few had ever been seen there, but that one bear had my employee’s undivided attention.

So the point is simple; a wonderful collection of pistols at home won’t do you any good, you’ll have to make do with what you have, Like the Boy Scout motto says, Be Prepared.

The author’s well-worn, and well-loved Ruger Blackhawk in .45 Colt is a perfect handgun for bear country.

Let’s get my own choices out of the way first. If I know ahead of time that I’m heading into black bear country, I like to carry my big handgun: a Ruger Blackhawk, chambered in .45 Colt, stainless finish with a 7 ½-inch barrel.

It was the first handgun I ever purchased, and I put a considerable amount of thought into it. That long pipe makes for a heavier gun, but I’m OK with that because the additional sighting distance and small velocity gain are both appreciated.

The Blackhawk is tough as nails, and while it may not have the prestige of a Colt Single Action Army, it is utterly dependable. Equipped with piano wire springs, the wisely designed transfer bar and adjustable sights, I am very confident with this pistol in hand.

The .45 Colt makes a formidable handgun cartridge, especially in a pistol as strong as the Blackhawk, where the pressures and velocities can be ramped up a bit. My gun will push the strong 300-grain hollow points to just under 1,200 fps, and that’s a formula that can end a confrontation.

My gun likes the Hornady XTPs best, and I feel confident making vital hits out to 40 yards or so with this combination. It’s certainly not the lightest sidearm – weighing in at just over 3 pounds, fully loaded in its holster – but when I’m forced to enter bear country, I have absolutely no worries.

The 7 ½-inch barrel makes for a bit more cumbersome handgun, but the author feels the accuracy is well worth it.

My other handgun, my day-to-day gun, is a well-worn Smith & Wesson Model 36, in .38 Special. It has a 1 7/8-inch barrel and a five-shot cylinder – in the classic snub-nosed configuration – and wears a set of Pachmayr grips, which feel better than the standard J-Frame grips in my hands. Is it a powerhouse, as a bear cartridge?

No, probably not, but I would feel much better with this gun – it’s easily concealable, doesn’t weigh a whole lot, nor take up a lot of room – than with no gun at all. With 158-grain bullets moving at nearly 800 fps, this probably represents – along with the 9mm Luger – the lower end of the spectrum, as far as a defensive bear gun goes.

Although lighter than what one would think of as bear protection, the author’s .38 Special is extremely compact, lightweight and portable.

A good .357 Magnum – and I really like the Kimber K6s – will definitely come in handy. The cartridge will push a 180-grain bullet to a respectable 1,300 fps, and that little Kimber has a lot to offer.

Lightweight and well-balanced, I had a chance to spend a bit of time with this wheelgun at the SHOT Show in Las Vegas.

Its lack of weight had me cringing at first, expecting some wrist-wrenching recoil, but I was pleasantly surprised with the manageability of the K6s. With a 3-inch barrel and a six-shot cylinder combining for a weight of just 25 ounces, this gun was made to be both carried and shot.

A Smith & Wesson Model 29, in .44 Remington Magnum – completely in the vein of Dirty Harry – still makes an excellent choice for the bear woods.

My buddy Marty Groppi – who enjoys the famous trout streams of Upstate New York – carries a Smith & Wesson Model 29 in the classic .44 Magnum, a combination that will most definitely save your bacon.

For those not familiar with this gun, think ‘Dirty Harry.’ The .44 Magnum is definite bear medicine.

Again, please keep in mind that we only have black bears to contend with here in New York. The grizzly and brown bears are a completely different story.

Dick Casull’s brainchild improves the ballistics of the .45 Colt – even in modern handguns – and provides an entirely different performance level for those who can handle it.

A grizzly bear is a formidable foe, having no issue whatsoever proving its dominance over human beings. In Alaska, meat is often removed from a kill site via a frame pack and two strong legs, and all that blood creates a scent trail like a flashing All-you-can-eat buffet advertisement.

In the springtime, when the streams are populated with fishermen, the bears are coming out of hibernation and are ravenous. Young cubs are emerging for the first time, and mothers are ultra-protective. A sidearm is a very smart idea. I’ve reached out for three gentlemen – all of whom I call a friend – for advice and a few experiences regarding their encounters.

Loaded with good ammunition, either of these Smith & Wesson .44 Magnums will make excellent bear medicine.

I’m sure that by now you’ve all heard about famous Alaskan bear guide Phil Shoemaker (grizzlyskinsofalaska.com) , who thwarted a grizzly attack with a Smith & Wesson 9mm automatic, loaded with Buffalo Bore hard cast ammunition. Phil has over three decades of experience guiding hunters and fishermen, and understands their habits as well as anyone else alive.

To recap quickly, Phil and his husband and wife fishing clients were walking through some thick brush to approach the stream they wanted to fish, when they heard a deep ‘woof’ and realized they had a bear close and angry. Long story short, Phil was forced to put the grizzly down.

He normally carries a .44 Magnum but opted for the 9mm that day. When I asked him for his thoughts on carry guns for bear country, Phil related the following: “Phil, I have always said that carrying any handgun for bear protection is similar to wearing a life jacket in a boat, or parachute in a plane. They only work if you have them with you.

In that vein, and considering the real vs. imaginary threat posed by bears, a familiar 9mm loaded with non-expanding bullets is a lot better than a heavy .44 or .500 you left at home or are not completely proficient with.” From one Phil to another, sage advice.

Just as with dangerous game rifles, using a cartridge that is too big to allow for proper shot placement isn’t a wise idea; shot placement is everything.

Cork Graham (corkgraham.com) , a fellow writer, hunter, and Alaska resident – not to mention an actor on the Discovery Channel – had a bit of a different perspective.

“In Alaska, we not only have to deal with the common two-legged variety of vermin found in every place in the world, but also the large, four-legged beasts that can either kill and trample you with their hooves, or rip you apart with their claws and teeth; it’s the latter which draw hunters to the Last Frontier with high-power, large caliber rifles.

Now, my colleague and fellow Alaskan Phil Shoemaker has effectively defended himself with a 9mm against a charging brown bear, but I prefer to carry a .45 ACP with me as my round.

It doesn’t kick as much as my .44 Rem Mag in a JP Sauer six-shooter that I used to carry on remote gold mining operations, and in a M&P Shield and Glock 21, it also serves as my concealed carry. Regarding my loads.

I’m partial to a 230 grain Federal Hydra-Shok jacketed hollow point staggered with 230-grain lead cast bullet, one following the other, the first round out of the magazine a Hydra-Shok.

I carry both in a Blackhawk Alaska Guide Holster in the field, and in a Galco leather CCW holster under my belt in town: since being on TV, I learned that stalkers can be just as dangerous a charging bear.

As a retired, longtime USMC colonel buddy of mine reminded me a few weeks ago, “you should be carrying, always.”

My colleague and friend Bryce Towsley (brycetowsley.com) is a veteran gun writer who has considerable experience with bears of all sorts.

He has spent more than a bit of time in pursuit of bears, hogs, and other game animals with a handgun, in addition to time spent in the Alaskan game fields. When I asked him for his insight, he was kind enough to respond in detail.

“There is a lot of nonsense out on the internet from people who have never seen a bear and have probably never cut up a dead critter to see what a bullet will do.

I have been involved in stopping several black bears intent on doing us damage and have stood two brown bear charges without shooting; although in one of them I probably should have pulled the trigger.

The black bears have been stopped with pistols, rifles, shotguns and once with an ax. (I have killed or watched others kill several with an ax when I was guiding. This one took exception.) I have skinned three browns, two grizzlies and more black bears than I care to remember.

Any bear is a big, tough critter and to stop them you will need to penetrate and break stuff like big bones or skulls.

“A powerful handgun with a tough, deep penetrating bullet is the key. It’s also probably a one or two shot deal, so firepower is irrelevant.

Those who think they can empty their Glock into a charging bear are fools. No matter what anybody says, Shoemaker got lucky with that 9mm on the bear.

I have seen that cartridge fail horribly on black bears and hogs. The result was a dead dog with one of the bears and almost a dead friend with one of the hogs.

If I had not shot the hog with a .44 Magnum I think it would have ended very badly. I know Phil has seen more bears killed than I ever will, but he got lucky. My rule of thumb is the minimum is 4-3-1. At least .40 caliber, 300 grains and 1,000 fps. More is always better and the bullet is the key. No semi-auto makes the grade except perhaps the .50 AE, but most ammo for that fails due to bullets. I have a buddy who guided a hunter with a .50 AE to a brown in the late eighties when it came out and it was a disaster. He saved them both, barely, with his .338 rifle.

The Freedom Arms Model 83, in .454 Casull, in a serious piece of gear. It will drive a 300-grain bullet to over 1,600 fps.

“The 12-year-old in Alaska who just shot the brown with the shotgun is the son of a good friend. His dad stopped a charging brown with a .500 S&W pistol a few years ago. They live off the grid and have lots of bear trouble with their livestock.

He lives every day with brown bears and has guided to dozens if not hundreds of them. He is a hard-core gun guy and he agrees with me on cartridges, guns and bullets.

“That said, here are my picks. The .454 Casull is my usual choice as it provides a good balance of power with manageability. I own several Casulls, but my favorite handgun is a 5-inch, custom Freedom Arms Model 83 that Ken Kelly tricked out for me.

My handloads push a 300-grain hard-cast bullet to 1,614 fps. I usually carry it in a cross-draw holster that allows me to ride a horse or ATV. If I am packing meat, I carry it in a shoulder holster. Both holsters always pack into camp with me. Before any bear country hunt I practice with it a lot.

It is the gun I used in the American Hunter Challenge Video where I make five hits at seven yards in under three seconds. The group was less than four inches and the ammo was full-power Winchester factory loads so it was full recoil.

I have used the Casull to take a lot of game including several black bears so I understand the terminal ballistics of this cartridge pretty well. Sometimes I carry a .44 Magnum with 300-grain cast bullets, but never anything smaller for bear protection. I have a short barrel S&W 629 that Ken Kelly modified. Handloads push a 300-grain to just over 1,000 fps, so it just cracks the code.

It’s very light and handy to carry. I also have a small Freedom Arms in .500 Wyoming Express. It can push a 400-grain bullet to more than 1,500 fps, but I can’t control it. I load them to just over 1,200 fps. It’s often with me in bear country and has made several trips to Alaska. My Ruger Blackhawk in .45 Colt with handloads, 300-grains, 1,200 fps (1,192 to be exact) goes with me on a lot of black bear hunts with hounds. It’s light and easy to carry.”

Put three or four gun writers in the same room, and you’ll usually get four different answers, but I think you’re seeing a common thread here. With the exception of Mr. Shoemaker – who has more experience than I will ever even hope to have – bigger seems to be better. Let’s hope that we can all avoid the threat of mauling, but if you’re unfortunate enough to have it happen to you, be prepared.

For more information about Federal ammunition, click here.

For more information about Hornady ammunition, click here.

For more information about Smith & Wesson, click here.

To purchase a sidearm for bear country on GunsAmerica, click here.