Category: Fieldcraft

What an idiot! Because you just know that Mommy Bear is close by and REALLY PISSED OFF!

___________________________________ Here is a little Tip in Field craft. In that Walt Disney’s world has nothing what so ever to do with the REAL WORLD. If you see any wild animal, Do Not Get Closer to it but instead put it in Reverse and get out of the Area.

Sighting in a rifle is an important thing to do if you want your rifle to be dead on when taking a shot.

Which brings us to the Carlos Hathcock way of sighting in a rifle.

For those that don’t know who Carlos Hathcock is, he was a United States Marine Corps (USMC) sniper with a service record of 93 confirmed kills.

Hathcock’s record and the extraordinary details of the missions he undertook made him a legend in the U.S. Marine Corps.

He was a serious threat to the NVA (North Vietnamese Army), which they placed a bounty of U.S. $30,000 on Hathcock’s head.

The following is a story by Gus Fisher a retired MGySgt USMC who talks of the time he met Carlos.

What was unique was the way Carlos had taught Gus to sight in a rifle. Here’s the excerpt from M14Forum:

As mentioned before, I was a very young Marine Sergeant when I came up to THE Marine Corps Rifle Team the first time as the junior Armorer.

I didn’t grow up using high power rifles. We used shotguns to hunt quail, rabbits, squirrels, pheasants, ducks and geese. I used a Mark I Ruger Target .22 pistol for racoon hunting and used a Model 74 Winchester .22 to really learn the basics of rifle marksmanship. My introduction to both high power shooting and long range shooting was in Marine Corps Boot Camp.

On Qual Day in Boot Camp, I ran 7 consecutive bullseye’s from the offhand position at 200 yards. The 8th round was a pinwheel bullseye, but it was on the target next to mine, so I got a maggie’s drawers. Knee High wind got me after that and I fell apart and only shot Sharpshooter in boot camp.

I bought a sporterized Mauser in .308 with a scope on it from a fellow Marine during the time I was going through the Armorer’s OJT program on Camp Pendleton. I used that for ground squirrel hunting, but was never really satisfied with my zero on the rifle.

So after I came up on “The Big Team,” I asked the second senior Armorer – Ted Hollabaugh, if he could show me how to REALLY sight in a rifle with a scope.

He said sure and he would do it, but since we had all the talent in the world at MTU, why didn’t I ask one of the shooters?

Well, I was a young kid and I didn’t know any of the shooters that well – most of them were much older than I. That’s when he suggested I ask Carlos Hathcock for some help.

I didn’t know Carlos then and did not know of his exploits in NM and Sniper shooting. Ted talked to Carlos about it and Carlos stopped by the shop later that afternoon.

Carlos looked at me and said, “So you want to sight in your rifle, eh? OK, thoroughly clean the bore and chamber. Dry the bore out with patches just before you come down to Range 4 tomorrow at noon on the 200 yard line. Have the sling on the rifle that you are going to use in hunting.” Then he went on about his business.

When I got to Range 4 the next day, he had a target in the air ready for me. He told me to get down in the best prone position I had. He checked me and adjusted my position just a bit. Then he said, “Before you shoot.

The MOST important thing I want you to do is take your time and make it the best shot possible. It doesn’t matter how long you take, just make it a good shot.

ALSO, and this is as important, make sure you give me an accurate call on where you think the bullet hit the target.” After I broke the shot, I told him where I thought the bullet had hit.

He checked it by using a spotting scope when the target came back up. He grinned just slightly and said, “not a bad call.” He then took a screwdriver and adjusted my scope a bit. He had me record everything possible about the shot and weather, humidity, temperature, wind, how I felt when the shot went off, what kind of ammo I was using, the date, and virtually everything about the conditions on the range that day.

I had never seen such a complete and precise recording of such things in a log book. He told me that if a fly had gone by the rifle and farted while I was shooting, to make sure I recorded that.

Then he told me to thoroughly clean the bore and chamber, and have it dry when I came back at 12 noon the next day. I was kind of surprised he only had me shoot once, but when you are getting free lessons – you don’t question or argue.

The next day, he told me the same thing. I called the shot and it was closer to the center of the bullseye. He made another slight adjustment and told me to clean the bore and chamber, dry the bore thoroughly and come back the next day at noon. Then we recorded everything possible about that day.

The following day, the shot was darn near exactly centered on the bullseye. Then he told me to clean and dry the bore before coming back the next day. Then we recorded everything about that day.

About a week into the process, Ted asked me how it was going. I said it was going really well, but we were only shooting one shot a day. Ted grinned and said, “How many shots do you think you are going to get at a deer? Don’t you think you had better make the first one count?” There was a level of knowledge and wisdom there that I immediately appreciated, though I came to appreciate it even more as time went on.

We continued this process with the sitting position at 200 yards, then prone and sitting at 300 yards and 400 yards. Then we went down to 100 yards and included offhand in the mix. Each day and each shot we recorded everything possible in the book and that included the sight settings for each position at each yard line. We also marked the scope adjustment settings with different color nail polish for each yard line.

When that was over after a few weeks, I thought I had a super good zero on the rifle. But no, not according to Carlos. He started calling me up on mornings it was foggy, rainy, windy, high or low humidity, etc., etc. and we fired a single shot and recorded the sight settings and everything else about the day. (I actually used four or five log books by the time we were through and put that info all into one ring binder.) I almost had an encyclopedia on that rifle. Grin.

Well, after a few months, we had shot a single round in most every kind of condition there was. Then about the 12th of December, it was REALLY cold and it seemed like an artic wind was blowing, there was about four inches of snow on the ground and freezing rain was falling. He called me up and told me to meet him at Range 4 at noon. I had gotten to know him well enough to joke, “Do you really want to watch me shoot in this kind of weather? He chuckled and said, “Well, are you ever going to hunt in this kind of weather?” I sighed and said, “See you at noon.”

By the next spring, I had records for sight settings for the first shot out of a “cold” barrel for almost any weather, position and range I would use and temperature/wind/humidity condition imagineable. He had informed me months before that was bascially how he wanted all Marine Snipers to sight in their rifles as only the first shot counts, though of course they would do it out to 700 yards on a walking target and further on a stationary target. They also practiced follow up shots, of course and we did some of that as well. It gave me great confidence that I could dial in my scope for anything I would come across.

Some years later in the late 90’s or really early this century, I was talking to a Police Sniper and he was really impressed I knew Carlos. I told him about the way Carlos had me sight in my rifle and suggested he do the same thing as he was a sniper for the Henrico Country SWAT team. He had never heard of that and took it to heart. About two and a half years later, he got called to a domestic situation where a husband had a handgun to his wife’s head and was going to kill her. After the Sergeant in charge and the Pysch guy determined the husband was really going to do it, the Police Officer was asked if he could hit the guy at just over 200 yards and not hit the wife. He said he knew he could (because he had followed Carlos method), so they told him to take the shot. One shot and the perp’s head exploded.

The wife was scared crapless, but unharmed.

When he told me about it about when I saw him the first time a week after the incident, the first thing I asked him if he was OK about taking the shot. He understood I was talking about the pyschological aspects and he really appreciated it. He said, it had bothered him a little that night until he remembered that if he had not taken the shot, the wife would have died. I checked back with him and he really was OK with having taken the shot. I’ve checked back every gun show I see him at and I know he is doing fine about it.

Sources: M14Forum

| July 26, 2016

If you’ve read the first parts of this land navigation manual, you should now know how to read a topographic map, find your bearings, and orient yourself with a map and compass.

You’re ready to start doing some serious land navigation. With the aid of modern technology at the outset, you can get a whole lot more specific with your land nav; rather than just finding your way to a major landmark, you can locate a little stake in the ground.

To do that, you plot MGRS (military grid reference system) coordinates on your map before you head out. Why would you want to employ this old/new method of land nav?

So you can be antifragile.

Two is one, and one is none; which is to say, technology fails, and you need to have a contingency plan for when it does. Soldiers are required to know how to plot MGRS coordinates on a map with nothing but a military protractor, and how to find those coordinates in the field with a map and compass. That way, if GPS fails on a mission, they can still make it to their intended waypoints – even if they’re small and specific; with MGRS coordinates and a military protractor, you can plot a point on a map within 10 meters of accuracy.

For civilians, knowing how to plot MGRS coordinates by hand and navigate to them can be useful for active outdoorsmen. Let’s say you’re planning a weeklong hunting trip out in the wild. Part of your prep work should be knowing the MGRS coordinates for your start point and your secluded hunting cabin out in the woods. You can plot those points on your map and you’ll have a backup navigation tool in case you lose your GPS device or if it fails.

Besides the practical uses of knowing how to plot coordinate points and navigate to them, it’s just plain fun to do.

Prep Work

Before we learn how to use MGRS coordinates and get out into the field, we’re going to do some prep work to make sure that we have all the information we need to navigate.

Plotting Your Coordinates on the Map

Using a GPS or an online tool, you can acquire 8-digit MGRS coordinates for the various spots you’re targeting during your trek in the wilderness. You’ll then need to plot those points on your map, using a military coordinate protractor.

I’ll walk you through how to do that, using for an example the eight-digit coordinate number: 30469530

We’re going to split that up for easier reading:

- 3046 (this is our easting coordinate — the vertical lines that run north/south on your map).

- 9530 (this is our northing coordinate — the horizontal lines that run east/west on your map).

When reading and plotting MGRS coordinates, follow the rule of “right and up.” I’ll show you what is meant by this by continuing our example.

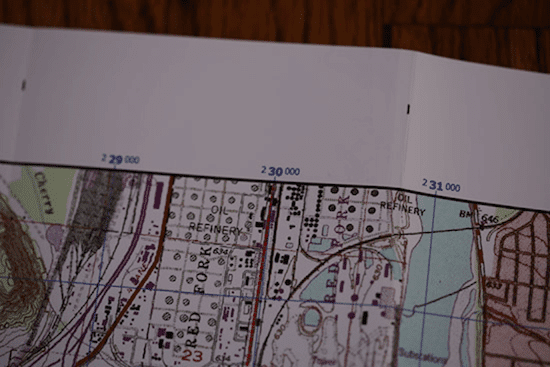

First, we need to find what square in our map we’re working with. To find that, we’re going to look at the first two digits in both the easting and northing coordinates. So our easting number is 30; our northing coordinate is 95.

Look at the top of your map at the easting numbers, and move right until you find the 30 grid line.

Look at the side of your map at the northing number and move up until you find the 95 grid line.

Follow the lines to where they intersect. That is the bottom left corner of the grid square that we’ll be working with.

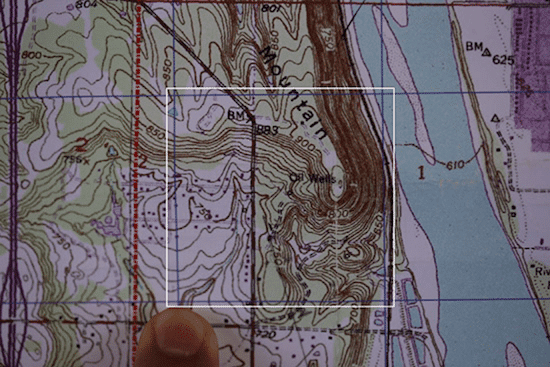

So we’re in this general area. Time to get more specific. With the next two digits in both our easting and northing coordinates, we’ll be able to get within 10 meters of our spot. To do this, we need to bust out our military protractor.

Your protractor will likely have different scale grids. Make sure you use the one that matches your map’s scale, or else you’re going to be way off on your plotting. The map I’m using is a 1:24,000 scale so I’m going to use the 1:24,000 scale grid on my protractor. The horizontal numbers on your grid are for measuring your easting co-ordinates; the vertical numbers are for measuring your northing coordinates.

1. Line up 0/0 on the bottom left corner of your grid.

The first step is to line up 0/0 on your protractor with the bottom left corner of the grid you’re working with.

2. Move protractor right until easting grid line is lined up with second two digits of your easting coordinate.

Let’s take a look at our easting coordinate again: 3046. We’re focusing on those last two digits right now — 46. That tells us our easting coordinate is 460 meters east from the 30 grid line. We want to move our protractor right until our vertical easting line is lined up with 4.6 on our protractor (4.6 represents kilometers=460 meters).

3. Move up on the slot on your protractor using the second two digits of your northing coordinate.

Take a look at our northing coordinate: 9530. We’re going to focus on the last two digits. The 30 tells us that our northing coordinate is 300 meters north of the 95 grid line. We want to move our pencil up until it lines up with 3.0. Place a dot there with your pencil.

Congratulations! You just plotted your first point using an 8-digit MGRS coordinate.

Continue the same process for any other points that you may have. I recommend putting a small number next to each dot to remind yourself of the order of your plots. You can see in the pic above, I wrote a “1” next to my plot.

Getting Your Bearings

Now that we have our coordinates plotted on the map, we need to determine the bearings from each coordinate to the next. We could use our compass as a protractor, but we’ll just use our military protractor because, well, it’s a protractor.

An easy way to do it is to simply draw a line from your first plot through the plot that you’re measuring a bearing on, like so:

Draw it lightly with your pencil (we’re going to erase it), and make sure it extends pretty far past your second plot.

Place your protractor on your map. In the middle of the protractor, you’ll see a little hole. Place that directly over your first plot.

Make sure 0° is in line with north on your map.

Look where the line you just drew on your map lines up on your protractor hashmarks. In this case, it hits the 165° mark.

So from point 1 to point 2, there’s a bearing of 165°.

In a notebook, write your bearing next to the coordinate for your first plot to remind yourself that when you’re at point 1, you’ll shoot a bearing of 165° on your compass to get to point 2.

So it would look like this:

- 30469530 165°

Now move to point 2 and repeat the same process to get the bearing for point 3. Write that bearing down in your notebook next to your coordinate for point 2 to remind yourself when you get to point 2, you’ll need to shoot that bearing on your compass to get to point 3.

Repeat the process until you’ve gotten bearings for all of your known MGRS coordinate points.

Measuring Distance

With our bearings, we know what direction we’ll need to walk to get to our various points, but how do we know how far we have to travel?

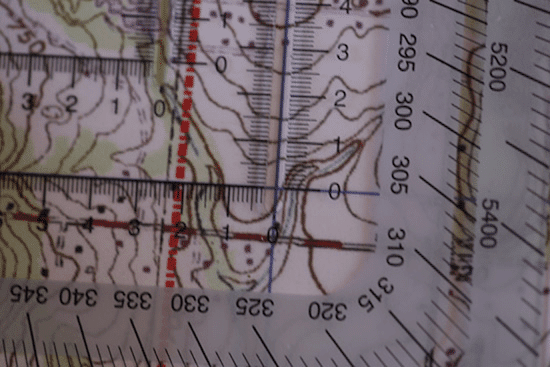

If your protractor has a distance scale, use it. Just make sure you’re using the scale that matches your map. In this case, our map has a scale of 1:24,000, so I’ll use that scale. Keep in mind that each number on it represents 100 meters.

Measure from point 1 to point 2. In the example above, the distance is 400 meters. Write down the distance next to your first coordinate. That helps me remember that when I’m at point 1, I’ll need to travel that distance to get to point 2.

So it would look like this in my notebook:

- 30469530 165° 400m

Measure distance from point 2 to point 3. Write it down next to point 2.

Repeat until you’ve gotten your measurements all the way to the end point.

Out in the Field

We’ve got our points plotted on our map and our bearings and distances written down. It’s time to start trekking.

Shoot Your First Bearing

We look down at our notes and see that next to our starting coordinate, we have a bearing of 165° to get to point 2. The distance to point 2 is 400 meters.

Get out your compass, and index your bearing to 165° and move your body until the needle is inside the box. Congratulations, you now know which direction you have to walk to get to point 2.

Start Walking and Track Your Distance

Because of the map work we did earlier, we know how far we need to go to get from point 1 to point 2. But how do we track how far we’ve gone when we’re out there walking?

Enter pace counting.

First, we need to figure out how many paces it takes for us to cover 100 meters. You can go to a high school track or use a measuring wheel to stake out your own 100-meter line.

Start with both feet at the start line and step off with your left foot and walk the 100 meters using your normal stride. Every time your left foot touches the ground, count it. When you get to the end, remember what your pace count was.

To make sure we have it keyed in, we’re going to walk back and count again to see if the second time is about the same as the first go round. For a man who’s about 6 feet tall, your pace count for 100 meters will be around 65-70.

So if you need to travel 400 meters and your pace count for 100 meters is 65, you’ll know that it will take about 260 paces to traverse that distance (400/100 = 4; 4X65 = 260). If you need to go 50 meters, you’ll know you need to go about 32 paces (65/2 = 32.5).

Keep in mind that uneven terrain and other environmental factors will effect your pace count. For example, if you’re going up or down a hill, you’ll likely take more steps to traverse 100 meters. Pace count won’t give you an exact measurement of distance, just a rough one.

If you don’t want to lose track of your pace count in your head, consider utilizing “ranger beads” or “pace count beads.” It’s a way for you to offload remembering your pace count to an external device. The folks at ITS Tactical have a great article and video on how to make your own pace count beads for this purpose.

Getting Around Obstacles

The way we’re doing land navigation requires us to walk in straight lines from one point to the next. What do we do if we come across an obstacle in our path, like a dense patch of scraggly mesquite trees or a pond? We’ll need to walk around it, but how do we do that without losing track of our distance and our bearing?

We’re going to do what’s called “boxing” the obstacle.

Let’s say we’re walking a line on a bearing of 165° and we’ve got 100 meters to go until our destination point. Problem is, there’s a small pond in our direction of travel.

To get around it and back on our original bearing while not losing track of our pace count, we’re going to box it.

Stop walking, but remember the pace count that you stopped at. Set a bearing 90° from your original bearing of 165°. That would be 255°. Walk at that 90° angle of your original bearing until you’ve cleared the pond and can move forward again. Remember that pace count — let’s say it’s 40.

Set your compass back to its original bearing of 165° and start walking again until you pass the obstacle. Let’s say it takes you 40 meters to pass the object. You’ve got 60 meters to go until your destination. Problem is, you’re 90° off of your bearing.

To get back to our bearing, we’re going to subtract 90° from 165 and set our compass to 75°. Walk until you’ve gone 40 paces. Stop.

Now add back 90° to get your original bearing of 165°. Walk forward 60 more meters. Congratulations, you’ve boxed an obstacle.

Conclusion

By following the guides we’ve given in this manual, you should be able to get started with learning the skill of land navigation. Of course, you’ll never get the hang of it just by reading — you need to get out there and practice! So get yourself a compass, map, and protractor and start toying around with them on the weekend. Yes, you’ll make mistakes, but that’s all part of the learning process. And if you’ve already learned the basics of land nav, I highly recommend getting out and practicing regularly. It’s a skill that degrades without use.

Until next time, shoot your bearings straight and stay manly!

Organization, planning and patience keys to success

Alligator hunting is one of Mississippi’s most challenging pursuits, and among some hunters it’s the most exciting. But those challenges can lead to a frustrating season for some. Ricky Flynt, Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Parks Alligator Program coordinator, explained some of the most common mistakes he sees.

“I’d have to say that the single most common mistake I see occurring among gator hunters is their failure to be prepared for the ‘Big One,'” Flynt said. “I’m not sure if it’s because they have low expectations of success, or if they simply are not experienced in what it takes to follow up after the harvest of a large alligator.

“For the most part, many hunters have never had their hands on a large alligator at all. It can be a little overwhelming for a first-timer once they are up close with a 10-foot or larger alligator and see just how cumbersome the carcass is to handle, much less to get it placed into cold storage.”

Because alligator season occurs in the hottest part of the year, Flynt said hunters need to have a plan in advance to cool their gator.

“An alligator carcass can ruin in quick order once the sun rises if there is not already a contingency plan in place,” Flynt said. “Access to walk-in coolers are the best option, but there are alternatives that work well if a person is creative.”

Get it together

“The second most likely mistake has to do with being organized,” Flynt said. “Alligator hunting requires a lot of different equipment, gear, and supplies.

“Just finding a place to store all of the necessary and potential items to be used in a boat and still have enough room to walk around in the boat can be quite a task, much less have it organized. Things can get very exciting very quickly. It can be all hands on deck at the drop of a hat.”

Because of that, Flynt said success can greatly depend on a group’s ability to adapt quickly and have the necessary items needed for the situation at hand.

“That means that everyone in the hunting party knows where everything is located and can get to it quickly,” Flynt said. “So, being disorganized can be the difference in success and heartbreak.

“Prepare well ahead of the hunt. Use a check list and check items off as you prepare your vessel for the hunt.”

Watch and wait

According to Flynt, patience is a virtue when it comes to alligator hunting. Not only can it improve your success, it can improve the quality of hunts for others.

“Alligators, compared to humans, are very patient,” Flynt said. “It is nothing for an alligator to submerge upon the approach of a boat and just go lay on the bottom of the river for 10 to 20 minutes, maybe over an hour, then slowly and stealthily resurface a short distance away with nothing but their eyes and nostrils above the water surface.

“People who are not familiar with alligator habits can run themselves ragged up and down the river approaching alligators only to see them submerge, then aborting to move on down the river looking for another alligator. This type of hunting is less productive and creates more disturbance of alligators and other alligator hunters.”

Flynt recommends that if you see a gator you want to harvest and it submerges, stick with it, be quiet, keep your lights on and watch for bubbles, ripples or moving vegetation.

“If a hunter watches for these clues, there is no need to keep moving when the alligator you are wanting to hunt is right under your nose, so to speak,” Flynt said.

Be safe

Although Flynt said all of his points are keys to a successful hunt, returning home alive and unharmed is the most important aspect of alligator hunting.

“Never take chances that could result in accidents that can result in serious mistakes, injuries or even death for yourself and others around you,” Flynt said. “Things can be very dangerous navigating the waterways at night. In fact, navigating the waters with multiple people and all of the equipment in the payload on a vessel is the most dangerous aspect of alligator hunting.”

Safety precautions:

• Wear personal floatation devices at all times.

• Follow boating regulations and have all safety gear on hand.

• Have first aid kits readily available.

• Keep cell phones in dry storage.

• Always make sure someone outside your hunting party knows the general location of where you will be hunting and where you are launching your boat.

• Keep plenty of water and sustainable food on board.

• Never consume alcohol while hunting.

And last, but not least, “Get plenty of rest,” Flynt said. “Alligator hunting can be extremely exhausting and an exhausted boat operator is a recipe for disaster.”

More Outdoors: This monster of an alligator once roamed Mississippi

More Outdoors: Schooling redfish mean fast, furious action

More Outdoors: Misinformation about chronic wasting disease circulating

More Outdoors: State acquires nearly 18,000 acres in south Delta

Editor’s Note: This guest post by Creek Stewart first appeared at willowhavenoutdoor.com.

You never know when you might need natural camouflage. Whether to escape and evade or to hunt and stalk, blending into the wilderness around you might be a necessary part of your survival scenario one day, and it’s important that you understand the basics. Luckily, the process is fool-proof, and perhaps surprisingly, fast.

The Base Layer

It all starts with muddin’ up! It goes without saying that this method of natural camo lends itself to warm weather scenarios. This process also works much better on bare skin. I started the whole process by stripping down to my skivvies and then scooping some goopy clay-mud mix from the edge of the pond. There’s really no delicate way to do this — just smear it on! Once you’re all mudded up, the next step is pretty easy.

Get it on nice and thick; a substantial, wet base layer is critical.

I had to go Garden of Eden style in these shots with a Burdock leaf for the sake of decency.

Duff and Forest Debris

Forest duff, debris, and leaf litter cover the floor in every type of forest environment. What better material to use than the stuff that exists naturally in the area that you’re in. Just grab handfuls of forest debris and slap it all over your wet, gooey base layer. It will stick, and as the mud dries, it will become cemented into place. You can even roll on the ground; you’ll be surprised what your fly-paper-like body will pick up.

I know what you’re thinking — it looks itchy. It’s not. The mud layer protects your body from all of the little leaf and twig pricks that you imagine might be happening all over my body. I’m also impressed at how well this keeps the mosquitoes at bay. It’s certainly not 100% effective, but it does help.

Now, Disappear

It’s amazing how quickly you can disappear using this simple two-step natural camo method. A few years back while giving natural camo a stab while hunting I actually had a squirrel run down the tree I was leaning against and eat a nut while sitting on my leg. I kid you not. I could tell he knew something wasn’t quite right but he had no idea he was sitting on a human! It was an amazing experience and that squirrel was delicious (just kidding, I didn’t kill him). And, yes, at that distance I could tell it was a “him.”

By the way, my skin feels amazing. I think I’ll start charging for “Natural Camo Full Body Treatments.”

Conclusion

Next time you find yourself being chased by a Predator from another planet, don’t forget what you learned here: get naked, mud up, and roll on the ground. In less than 5 minutes you’ll be an unrecognizable fixture in the forest around you.

Remember, it’s not IF, but WHEN.

Listen to my podcast with Creek about survival and prepping skills.

___________________

Creek Stewart is a Senior Instructor at the Willow Haven Outdoor School for Survival, Preparedness & Bushcraft and the host of the Weather Channel’s Fat Guys in the Woods. Creek’s passion is teaching, sharing, and preserving outdoor living and survival skills.

© by Sniper’s Hide

Mils or MOA

This debate is never going to end, but we should agree on the facts. Every day we see the uninformed arguments how one angular unit of measurement is better than the other. The truth of the matter is, one is not better, they are just different ways of breaking down the same thing.

Personally, outside of the disciplines like Benchrest Shooting and F Class, I think Minutes of Angle should be retired. We have bastardized the unit to the point people have no idea a true MOA is not 1″ at 100 yards, or 10″ at 1000, but 1.047″ and 10.47″ at 1000. If you round this angle, you create errors at the longer distances. Today we shoot a lot farther than before, 5% of error compounding at an extended range will cause a miss. In fact, this is one of the main reason your ballistic software does not work. You default to MOA when in reality your scope adjusts in Inches Per Hundred Yards.

Shooter MOA or Inches Per Hundred Yards (IPHY) is not a True MOA, and yes it does matter when companies mix them. Having someone question how IPHY is different when they don’t understand we don’t use 1 MOA or even 10 MOA to hit a 1000 yard target is frustrating to explain. If we consider a 308 as a point of reference, we are looking at almost 17″ of variation between the two units of adjustment.

We can quickly point to the adoption of Mils here with the Military to demonstrate the ease of use, but then the Americans reading this will argue how they think in Inches and Yards as if Mils only work with the metric system. Mils are base 10 and unfortunately Mr & Mrs. America thinking in fractions is nowhere as simple.

3600 inches is 100 yards, 1/1000 of that is 3.6″ and adjusting in .1 mils means we moved the bullet .36″ per click at 100. See what we did there, we moved the decimal point. Some people believe an MOA is a finer unit of adjustment. Failing to note that: .3 Mils is 1.08″ at 100 yards. Contrary to popular belief you can get a Mil Based scope that moves the reticle .18 Inches per click. Mil based scopes usually adjust in .1 Mil Increments; however, they do make scopes that adjust in .05 Mils.

While Milliradians were added to the metric system many years ago, it was never designed to be a metric only unit and works outside the metric system as this is an angle. Every angle has a linear distance between it. You should be ignoring this fact and using the angle vs. picking a linear value to adjust your correction. If I am shooting 873 yards away, saying the bullet 6″ off the target is neither honest or accurate. You’re guessing; in your mind, it looked six inches away, but what if it was 9″? Using the linear value is more work, why not just adjust the angle?

Minutes of Angle started out like that too, but unfortunately, companies took shortcuts and ruined it for everyone. It was easier to manufacturer 1″ vs. adding in the .047″. Long range back in the day was between 400 and 800 yards. Read any old school book on ballistic, and it rarely goes past those ranges in their examples. Today we are shooting beyond 1000 yards, so it matters more than ever, you have to take it into account.

Defaulting your program to MOA when you are using IPHY is a significant point of error. JBM online is a great place to demonstrate this as you can include both MOA and IPHY in the output. The same amount of adjustment is accomplished with two different values. Mix these numbers, and the result is a miss. Did you dial 40.1 or 38.3 MOA?

I highly recommend you map and calibrate your MOA scope to confirm it’s actual value. It works both ways, not every MOA based scope is TMOA, some are SMOA. The compounding error is a lot bigger than .47 inches.

One is not more accurate than the other. I can hit the center of any target using either unit of adjustment. Using JBM the same way we can see that both correctly move us to the target. The difference is less than a bullet width. I have no trouble zeroing or hitting the center of a Shoot N C target keeping me squared away.

Which unit of adjustment is right for me?

This is the ultimate question; it should not be up to someone else to answer it for you. Communication is your number one consideration.

What are your friends and fellow competitors shooting?

You want to be able to communicate and understand what a fellow competitor is talking about when he walks off the line. You can convert using 3.43, by multiplying or dividing the competing unit of adjustment against the other. That will give you a direct conversion.

12 MOA / 3.43 = 3.5 Mils

4.2 Mils x 3.43 = 14.4 MOA

Next, you have your reticle choices. You will find more versatile options when it comes to Mil Based scopes vs. an MOA one. That is changing a small amount as manufacturers adapt. But a reticle with 1 MOA hash marks is not as fine as a scope with .2 Mil lines in it. You now have to break up an already small 1 MOA into quarters. The Mil based scope is already breaking up the Milliradian for you.

Pick the reticle based on your initial impression as well as your use. You don’t need a Christmas tree reticle to shoot F Class. You don’t want to use a floating dot bench rest scope for Tactical Style Competition. Put your intended use into the proper context.

There are a lot of articles about the nuts and bolts of Mils and MOA. You can dig deep or understand we are using the angle and there is no need to convert to a linear distance. A Mil is a Mil, and an MOA is an MOA (Unless it’s not because you didn’t check) Today I don’t even teach, 1″ at 100, 2″ at 200 yards, 5″ at 500 yards. It’s an unnecessary step and confusing to a lot of people. Not to mention, it’s not right, that is IPHY, not MOA.

We match our scope reticle to our turret adjustment, so at the end of the day, “What you See is What You Get.” It matches what we see in the reticle so we can dial the correction on the turret. A super simple concept that allows the shooter to use the calibrated ruler 3 inches in front of their nose. That calibrated ruler is called a reticle taking away the need to “Think” about the adjustment, you just read it.

If the impact is off in any direction, you measure with the reticle and then translate that reading directly to the turrets. 1 Mils is always 1 Mil, and 1 MOA in any direction is a 1 MOA correction on the turret.

If you have not made the change to Mils, consider it. You will find it’s much more intuitive. You do not have to be a resident of Germany to understand it, and you do not have to use it with Meters. All my data is in yards, and mils directly translate to whatever range you use.

Sniper’s Hide mission is to uphold the traditions of those who came before us by expanding on the Science of Long Range Shooting while developing the Art of Precision Rifle Marksmanship.