Category: Fieldcraft

Makes sense to me

Sorry but this first draw in this video, looks like and excellent way to blow ones private parts away. So dear readers, try to convince me otherwise. Grumpy

ADVICE FOR LIFE

I will hereby lay claim to the spurious honor of being the world’s foremost “good example of a bad example,” especially in the arena of personal safety.

Through a lifetime spent as a cop, adventurer and shooter, I’ve managed to make nearly every mistake possible yet lived to tell about it. Fortunately, I’m also a testament to why luck and a benevolent Supreme Deity are a nice fallback when you’re dumb. And — let’s be frank — almost all of us are dumb once in a while.

Well, maybe not Massad Ayoob, but pretty much everybody else does foolish things on occasion.

This overview of personal (dis)qualification is given to explain why I have both the temerity and experience to present my own collection of the 50 most important rules of personal safety. They’re not the only principles for dealing with danger, especially of the social and interpersonal variety, but I think they’re a good start.

Some of this information comes firsthand from the countless “real-deal” folks I’ve had the honor of knowing, some comes from training, still more comes from direct observation of rapidly-coagulating pools of blood and the remainder was learned from The University of Life, School of Hard Knocks, Bachelor of Science in Blunt Trauma and Gunshot Wounds. I’ll allow some of these points are a bit facetious and snarky, but then again, so is life.

So, without further ado, I present “My 50 Rules for Life.”

1. There is no “ultimate manstopper” except perhaps a 105mm High Explosive shell.

2. Shot placement is far more important than caliber, energy, velocity, momentum or advertising hype. Remember the .22 Long Rifle has killed things as large as grizzly bears while a miss with a .458 Win does nothing but punch holes in the blue sky.

3. Wearing “cool guy gear” doesn’t make you cool. Brand-new “cool guy gear” will make you look like a poser. A plate carrier — with multiple witty “morale” patches, of course — worn on the range merely for visual effect when you’ve never actually worn one “in the field” makes you an Ultra-poser with Extra Posing Sauce.

4. The bigger the cleavage on the advertising copy, generally the worse the product. Nowadays, with political-correctness being in fashion, you see less and less of this. Of course, some of us sure miss the old days.

5. Fear is natural. Embrace it and learn to use it to your advantage. Invite it into your home, make it dinner and let it drink your best bourbon because being “fearless” means taking stupid risks.

6. The more combat a person has seen, the less likely they are to talk about it.

7. Scars are nature’s way of saying “I screwed up.” They also make for good graphic training aids and sometimes can even get you a free beer, though the cost/benefit ratio is not usually worth it.

8. Courage is the first requirement of success in a crisis. It’s easy to “talk the talk” but you should really test your courage periodically in some way to make sure it hasn’t died of inattention — or never really existed in the first place.

9. Even a ruggedized, fully redundant, satellite-enhanced, broadband-data-capable multimillion-dollar tactical communication network will break down under adverse conditions such as dew or nightfall.

10. A sense of humor will get you through anything from a gunshot wound to a divorce. It’s hard to think of droll comments when suffering a sucking chest wound during court proceedings, but it does help lighten the mood.

11. Everything on the internet should be considered “For Entertainment Purposes Only.” By now, hopefully everyone has realized “SuperDeathSEALKillerCommando99” on an internet forum is probably a morbidly-obese 13-year-old gamer on a laptop.

12. Gun store clerks come in two flavors: aficionados and salesmen. It’s your job to know the difference.

13. Any product with the word “miracle” in the title isn’t. Any shooting technique named after its developer — as named by said developer — is probably the same thing.

14. Trust no one except your mother. Keep an eye on her.

15. Being alert will prevent 99% of problems. If you are alert, you’ll be much more ready for the remaining 1% which are a problem.

16. Do unto others as they would do unto you; just make sure you do it first.

17. Death loves a braggart. Everyone else loves to see him get kicked in the groin — therefore, don’t ever brag about your tacti-cool-ness. See rule #3 and #6.

18. There is no such thing as a fair fight. If you fight, don’t be fair. This is why many old, slow, creaky guys are still very dangerous.

19. We should do more to include our loved ones in crisis preparation and training.

20. If you know it all — you don’t.

21. There is someone who is tougher, faster, a better shot or just plain luckier somewhere out there in the world. Remember this when considering a fight you could otherwise avoid.

22. The corollary to #21: There is no shame in avoiding a problem. This is otherwise known as “wisdom.”

23. The first rule of knife fighting is “Don’t get into a knife fight.” If you are in a knife fight, the best self-defense technique is applying a magazine full of large-caliber bullets as quickly as possible.

24. Anything and everything can and will fail at the worse possible moment. Plaintiff’s Exhibit #1 — Viagra.

25. We could all use a little more cardiovascular exercise.

26. When in doubt, doubt. Your “little inner voice” is world’s smarter than you give it credit for.

27. Virtually everything you see on commercial television is staged. Everything … as in everything.

28. If you don’t practice a movement at least 500 times (some say 2,000), you will never perform it correctly under stress. This is an iron-clad, unbreakable rule we all ignore.

29. A vehicle will kill you just as dead as a high-powered rifle. Always respect traffic.

30. No instructor is God. Some can reach demigod status after decades, many of them are pretty good and few of them should be prosecuted for false advertising. Beware the Cult of Personality, especially if you are new to firearms training classes — almost everybody seems brilliant when you’re new!

31. There is nothing wrong with blued guns, revolvers, leather holsters or firearms without “cutting-edge aerospace technology.” Then again, there’s nothing wrong with “black guns” either. Don’t be dogmatic.

32. The human brain is the deadliest weapon ever invented.

33. You’ll never wake up knowing “today is the day.”

34. Practice doesn’t make perfect; perfect practice makes perfect.

35. If you can’t tie a trustworthy knot, change a tire, kill your own food or perform basic first-aid procedures, you are not really prepared.

36. There is no one-weapon system, tactic, technique or school of thought to address every situation. Those who believe such claims are positively delusional.

37. Murder is wrong, while killing is sometimes necessary and excusable. Make sure you are okay with this idea. If not, you shouldn’t carry a weapon.

38. You are personally responsible for the right to keep and bear arms. Take this responsibility seriously or the gun magazines of the future might be pretty dull —“Cover story: A bar of soap in a sock — the ultimate manstopper!”

39. There is always “one more” — one more gun, one more problem, one more knife, one more bad guy.

40. Our opponents are frequently smarter than we give them credit.

41. A bad outcome in the legal system after a justified use of force can be just as devastating as a major gunshot wound. Know your legal rights and responsibilities.

42. Never get between two people fighting.

43. Train yourself to relax during and after stressful events. You’ll perform better and even live much longer.

44. Go somewhere inspiring and meditate on the concept of “honor.” Do this regularly and you are less likely to do something cowardly or immoral.

45. Guns and alcohol don’t mix. If you drink, you must be unarmed. If you can’t live by the rule, don’t drink. This rule personally chafes me, but I follow it religiously.

46. Never stand in a doorway.

47. Use light to your advantage. Whenever possible, just flick light switches rather than using a flashlight. Then again, if you aren’t proficient with flashlight shooting techniques, you are at a disadvantage in many dangerous encounters.

48. Always carry a knife, a gun and a light. Two is better, but one is critical.

49. “Preparedness” or “being tactical” should be an unspoken lifestyle, not a publicly shared hobby.

50. Buy a three-year subscription to GUNS for every one of your friends, family members, acquaintances and random homeless people on the street. You’ll end up richer, thinner, have more friends and be gloriously rewarded in the afterlife, or my name isn’t Hilary Clinton.

GRAPHIC: MAN THOUGHT STEEL-TOED BOOTS WOULD STOP A .45-CALIBER BULLET

It doesn’t take a smart person to guess it would be a bad idea to shoot your steel-toed boot with a .45.

We can thank this guy with a grimace for teaching everyone how bad of an idea this was.

The images surfaced on a forum and they are extremely graphic, so proceed with caution.

“This guy and his co-workers were discussing whether a steel toe boot would withstand a round from a .45, so what do do you think would be the best way to test this theory? YUP, you guessed it. Good thing he wasn’t testing his hard hat.”

Based on the placement of the shot, it almost appears the shooter missed his boot’s steel-toe insert in his boot. This might be a blessing in disguise, preventing metal shrapnel from spreading throughout the foot.

Let this be a not-so-friendly reminder to practice gun safety.

Transporting Firearms and Ammunition, a Frequent Flyer’s Perspective

U.S.A. –-(Ammoland.com)- Recently I was talking with a few fellow gun owners about air travel and the transporting of firearms. I was surprised at how some of them thought that flying with firearms was more of a hassle than it is in reality. These were not casual shooters, either. Industry professionals would be a better term.

For decades flying with guns has been part of my way of life when traveling from point A to point B, whether to attend a trade show, go on a hunting trip, take a class or simply visit family and friends and want the security of my carry guns.

Air travel with firearms can be as difficult or complex as you want to make it or it can be very simple.

The most important thing to ensure is that your firearms and ammunition are legal in both your point of origin and destination.

The Rules

According to the TSA (Transportation Security Administration):

“When traveling, comply with the laws concerning possession of firearms as they vary by local, state and international governments. If you are traveling internationally with a firearm in checked baggage, please check the U.S. Customs and Border Protection website for information and requirements prior to travel. Declare each firearm each time you present it for transport as checked baggage. Ask your airline about limitations or fees that may apply. Firearms must be unloaded and locked in a hard-sided container and transported as checked baggage only. Only the passenger should retain the key or combination to the lock. Firearm parts, including magazines, clips, bolts and firing pins, are prohibited in carry-on baggage, but may be transported in checked baggage. Replica firearms, including firearm replicas that are toys, may be transported in checked baggage only. Rifle scopes are permitted in carry-on and checked baggage. Declare the firearm and/or ammunition to the airline when checking your bag at the ticket counter. Contact the TSA Contact Center with questions you have regarding TSA firearm regulations and for clarification on what you may or may not transport in your carry-on or checked baggage.”

“Unloaded firearms may be transported in a locked hard-sided container as checked baggage only. The container must completely secure the firearm from being accessed. Locked cases that can be easily opened are not permitted. Be aware that the container the firearm was in when purchased may not adequately secure the firearm when it is transported in checked baggage. Ammunition is prohibited in carry-on baggage, but may be transported in checked baggage. Small arms ammunition, including ammunition not exceeding .75 caliber and shotgun shells of any gauge, may be carried in the same hard-sided case as the firearm. Firearm magazines and ammunition clips, whether loaded or empty, must be securely boxed or included within a hard-sided case containing an unloaded firearm. Read the requirements governing the transport of ammunition in checked baggage as defined by 49 CFR 175.10 (a)(8).”

The Container

You have basically two routes you can go here as far as a container.

- Use a dedicated hard-sided container for firearms

- If flying with a pistol or two, place your locked pistol case inside another piece of checked luggage.

When I fly, I always go with the first option. You may think that this only makes sense when traveling with a long gun and using a $300 wheeled and lockable rifle case and that certainly is an option. However, I found a case that fits not only my needs for flying with a few handguns but other valuables I do not trust to the good graces of an airport’s baggage crew.

It is the Pelican 1510 “Carry-On Case”, but do not let the name fool you, Pelican calls it that as it meets the maximum dimensions for carry-on baggage with most commercial airlines: 22.00″ x 13.81″ x 9.00″ (55.9 x 35.1 x 22.9 cm). Although, to be honest, it is a lot smaller than what I see most air travelers fly with as carry-on items.

Seriously, when did one bag and one personal item become two steamer trunks made in the 1920s with wheels and collapsible handles?

The interior gives you 19.75″ x 11.00″ x 7.60″ (50.2 x 27.9 x 19.3 cm) of secure storage space and the case can be ordered in a variety of colors (black, orange, yellow, red, green and tan). Additionally, you can configure the interior to how you want it.

Most shooters opt for the foam configuration and pluck out the shape of their firearm(s). I find this wasteful and recommend either the Trek Pak Divider system or the padded dividers. This allows me to use a second internal pistol case with my firearms and gives me plenty of room for other items I like to keep under lock and key such as cameras, night vision, thermal imagers, rifle parts, suppressors, ammunition and custom knives.

That is the second benefit of flying with a firearm; since it is transported in a locked case you can place other valuables with it for their protection.

Pelican’s 1510 case is small enough that it is easy to get around with due to its strong polyurethane wheels with stainless steel bearings and retractable extension handle, yet big enough that it cannot be secreted out of a secure area within an airport by a baggage thief. The padlock inserts are reinforced with stainless steel hardware and if you use quality padlocks, your guns and gear will usually arrive safe and sound.

If you think this is too much luggage to haul around with your other bags and are just transporting a handgun or two for concealed carry, you can place a small locked pistol case inside another piece of luggage. The pistol case must be locked, but the outer case cannot be. In my opinion this still leaves your pistol case open to theft as someone can reach in, remove the locked case and get it to a location where it can be pilfered or (if the case is small enough) stolen outright.

Firearms

“United States Code, Title 18, Part 1, Chapter 44, firearm definitions includes: any weapon (including a starter gun) which will, or is designed to, or may readily be converted to expel a projectile by the action of an explosive; the frame or receiver of any such weapon; any firearm muffler or firearm silencer; and any destructive device. As defined by 49 CFR 1540.5 a loaded firearm has a live round of ammunition, or any component thereof, in the chamber or cylinder or in a magazine inserted in the firearm.”

On one occasion while flying through Phoenix International Airport with firearms, a fellow passenger took note of us putting padlocks on my Pelican case and asked me how I was able to do that. He routinely transported high end electronics and did not trust the security of “TSA Approved Locks”.

I told him that I was transporting firearms and suggested he could do the same, by placing a firearm in his secured case with proper locks. He seemed hesitant but then relieved when I told him that TSA considers a pellet gun or starter pistol a fully-fledged firearm and a $20 non-gun would protect his case’s other more valuable contents.

Ammunition

When flying with handguns for CCW, I take along about 150 rounds in the original factory boxes. If I am attending a class that requires more (say 500 to 2000 rounds) I either buy it locally or have it shipped to the final destination.

As noted previous, ammunition may be stored in magazines, plastic reloading cases or the original cardboard containers.

If you are flying with a substantial amount, this is where the rules of the airlines come into play as many have specific weight allowances for ammunition. The limit seems to be 11 pounds on average.

Documentation

Oftentimes, ticket counter agents or even TSA Agents may not completely know the rules. I advise printing out copies of the regulations governing firearms from the TSA Website as well as the airline’s requirements for the same in advance of your trip to present it when difficulties in communication occur.

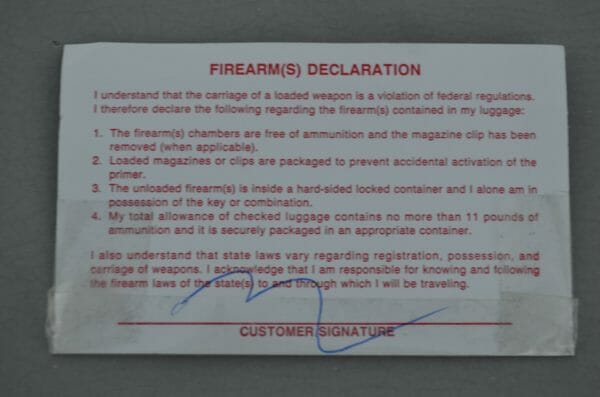

When you declare your firearm, you will be given a declaration form to place in the case containing the firearm after you complete it. You may be asked to wait nearby for up to 30 minutes as the bag is checked in case TSA feels the need to inspect it. If TSA does not arrive, proceed to passenger screening and on to the gate.

When you reach your destination and retrieve your baggage it may come out on the carousel. Some airports will take secured baggage to an office near the baggage claim or a roped off area in the vicinity. Claim your bags and be on your way, it is that easy.

About Mike Searson

Mike Searson’s career as a shooter began as a Marine Rifleman at age 17. He has worked in the firearms industry his entire adult life as a Gunsmith, Ballistician, Consultant, Salesman, Author and was first certified to teach firearms safety in 1989.

Mike has written over 2000 articles for several magazines, websites and newsletters including Blade, RECOIL, OFF-GRID, Tactical Officer, SWAT, Tactical World, Gun Digest, Examiner.com and the US Concealed Carry Association as well as AmmoLand Shooting Sports News.

I have Blogged many times about the Boer War and the indifferent British commanders that were in the Army at the time. I had commented that the British Soldiers were unmatched but their commanders were with few exceptions unremarkable to put it politely.

I bought a book in the early 90’s called “The Zulu Wars” and a bit later a book called “The khaki and the Red”. These books were fascinating to read the different history and battles that the Victorian era British army faced in defending the empire and “PAX BRITANNIA”.

Those books along with a book I used in college called “The Defense of Duffers Drift” which talked about small unit tactics during the Boer war. Some of the stuff was no longer relevant but it encouraged critical thinking. One of my favorite movies is “Zulu”, having the British soldiers stand and fight the word I remember from the movie was “Get some good pikeman”, for the use of the bayonet would be needed.

As I recall part of the British soldier to deal and adapt was part of the Victorian heritage that was prevalent at the time, the British soldiers and the culture believed that they were superior to everyone because they were British, it was part of the DNA.

For this reason they pushed the sphere of influence to a point where it was said that “The Sun never sets on the British Empire“. Also I remembered another movie with Michael Caine and Sean Connery “The man who would be King”

The Movie “The Man who would be King” was written by Rutyard Kipling, the same person that wrote the “Jungle Book” and he wrote ““Tommie” and many other things.

I ran across this article and I figured that it would tie on good with stuff that I had written.

DURING THE SECOND BOER WAR’S BATTLE OF SPION KOP, THE BRITISH EMPIRE CAME FACE TO FACE WITH AN INDIGENOUS ENEMY THAT EASILY MATCHED IT IN FEROCITY.

by Herman T. Voelkner

The century of conflict that would introduce the concept of total war to the world had its bloody roots on an obscure hilltop in the remote South African veldt. The Boer War, the last imperial struggle of the British Empire, would serve as the dividing line between the era of small, localized wars fought largely at the speed of hoof and foot and the global, mechanized slaughter that would follow. It would also prefigure the dismaying pattern of conflicts to come—the use of barbed wire, the introduction of concentration camps to contain Boer prisoners and their families, and industrial-age innovations in human-killing weapons. “War, which was once cruel and glorious, has become cruel and sordid,” globetrotting adventurer Winston Churchill would complain after observing the short, sharp conflict between his nation and the Republic of South Africa. It was—literally and figuratively—the beginning of the 20th century.

The war had a golden pedigree. When the precious metal was discovered in enormous quantities in the Transvaal region of South Africa in the 1880s, it roiled an already troubled situation. The Boers, itinerant Dutch-descended farmers, already had voted with their feet 60 years earlier in the “Great Trek” northward away from the growing British presence in the south. Now they were growing increasingly restive. Fiercely independent, they wanted no part of British intrusion into their public and private affairs, particularly the accompanying moral lectures on the burghers’ need for kinder, gentler relations with their slaves and servants. In 1881, Boer militia had ended the first armed conflict with Great Britain by hacking to pieces a British force at Majuba Hill. Humiliated, the British government acceded to self-government in the Boer republics of Transvaal and the Orange Free State. (The South African colonies of Natal and Cape Colony continued to fly the Union Jack.) Two decades of uneasy peace followed.

GOLD RUSH LEADS TO WAR

The ensuing gold rush into the Witwatersrand upset the delicate political balance, bringing an unwanted influx of English prospectors into the heart of the Transvaal. These “Uitlanders,” as they were called, were close to forming a majority in the region. During an era when the world’s economy ran on gold, Great Britain saw in the large expatriate presence a heaven-sent opportunity for expanding its influence in its former territories. The Boers were well aware of the demographic danger. A clear indication of that danger came in the notorious Jameson Raid of 1895. Instigated by Cape Colony Prime Minister Cecil Rhodes—creator of the DeBeers diamond fortune—the raid began when Rhodes protégé Starr Z. Jameson led a force of Cape Colony volunteers into the Transvaal to coordinate an attack with restive Uitlanders in the boomtown of Johannesburg. The plan went disastrously awry when the rebellion did not spread as expected—opposition to Boer rule had been overestimated. Jameson and his men were quickly rounded up and handed over to British authorities, who gave them a mere slap on the wrist, further outraging Boer sensibilities.

Weapons and ammunition poured into the Boer republic from the Netherlands and Germany, which was eager to see Britain humbled again by the Boers. Old Martini-Henry rifles were replaced with modern German-made Mausers, and “God and the Mauser” quickly became the Boer war cry. Meanwhile, Transvaal President Paul Kruger roughly suppressed the Uitlanders, refusing them the right to vote and resisting intense British diplomatic pressure. Diplomatic entreaties might be ignored, but as Kruger and his countrymen gazed across the border, they saw something they could not control: shiploads of British Army reinforcements steadily disembarking in Cape Colony and Natal. The Boers must act or face a swelling tide of British soldiers. Kruger issued an ultimatum: Unless the British buildup ceased and its forces withdrew from the frontier, the Transvaal would fight. On October 11, 1899, the ultimatum expired, and war for control of the fabulously wealthy region began. The words Kruger had spoken to his countrymen after the discovery of Transvaal gold—“Instead of rejoicing you would do better to weep, for this gold will cause our country to be soaked in blood”—were now sadly prophetic.

The Natal-based garrison at Ladysmith, where colonial governor Sir George White was in residence, was one of the keys to the British defense; Kimberly and Mafeking were the others. The three cities ringed the perimeter of the Boer republics. The Boers understood this and took immediate steps to forestall any offensive moves by the British. Kimberly and Mafeking were surrounded. (In the latter township, Lord Baden Powell would organize the boys of the town into the first troops of Boy Scouts.) In the British cantonment at Ladysmith, White and 12,000 troops were under imminent threat of capture. A British general of great renown, Sir William Penn Symons, already had been killed by a Boer sniper; his infantry brigade, reeling back from the extreme north of Natal, was now retreating toward Ladysmith. Feeling that destiny was on their side, the Boer inhabitants of the two British colonies were now rising in rebellion, turning the preexisting political demographic on its head.

For the British, the news everywhere was grim. Winston Churchill, who sailed over to Cape Town from England with General Sir Redvers Buller, the commander-in-chief of British forces in South Africa, reported back caustically that the British could “for the moment, be sure of nothing beyond the gunshot of the Navy.” It was far from clear that Buller was the right man for the job. Although he had four decades of military experience behind him, as well as a Victoria Cross, Buller was unused to fighting any enemy with a level of sophistication higher than that of the Zulus. Engaging him now was a highly motivated mounted force both nimble and armed with modern weapons. In a moment of candid self-appraisal before the war, Buller had said, “I have always considered that I was better as second in command in a complex military affair that as an officer in chief command.” This was the man who now faced the daunting military task, defending the two British colonies in South Africa from a determined and resourceful enemy equally at home on the veldt or in the mountains.

CHURCHILL TRAVELS TO THE FRONT AND GETS CAUGHT

While Buller remained at Cape Town to sort things out, an impatient Churchill teamed with journalistic colleague John B. Atkins of the Manchester Guardian to go to the front at Ladysmith before other journalists could do so. The two took a 700-mile train ride on an undefended rail line that brushed against Boer strongpoints along the way. They then boarded a small steamer bound for Durban and immediately sailed into the teeth of an Indian Ocean storm. After several harrowing and wretchedly seasick days, the pair arrived at Durban to learn that Ladysmith was completely surrounded by Boers. Still determined to get to the fighting, Churchill and Atkins made another dangerous train ride of 60 miles that brought them to the end of the line at Estcourt. From there, they could hear the cannonfire at Ladysmith reverberating in the distance against tin-roofed shacks.

On November 14, Churchill was invited to participate in a reconnaissance by armored train, a dubious venture vulnerable to the simplest of countermeasures—a blocked track, a disturbed rail, or a blown bridge. The Boers, under their new commander, Louis Botha—two months earlier a Boer private—speedily obliged. A blockade sufficed; the train rammed boulders strewn along the track. Heavy rifle fire and shrapnel rained down from the hills. For over an hour the train was under fire as Churchill assisted in the defense and attempted escape. “I was very lucky in the hour that followed not to be hit,” he recounted later. “It was necessary for me to be almost continuously moving up and down the train or standing in the open, telling the engine-driver what to do.”

Churchill personally directed the recoupling of the cars in an attempt to ram the blockade, and when that failed, he led a group of wounded soldiers to relative safety beyond a nearby trestle. He was returning to lead more away from danger when he met some figures clad in slouched hats—Boers, he realized—leveling their rifles at him from a hundred yards away. He turned and ran in the other direction, bullets striking all around him. Minutes later a horseman appeared and pointed his rifle at the Englishman, who automatically reached for his pistol, only to find that he had left it on the train. He was taken prisoner after managing at the last second to discard two magazines of prohibited dum-dum bullets. With that, England’s preeminent warrior-journalist was led away to prison, his slyly discarded magazines very likely saving him from drumhead execution.

‘BLACK WEEK’ FOR THE BRITISH FORCES

While Churchill languished in Boer custody, depressing news filled the grim dispatches from South Africa to England. In the space of one week—December 10-15—the British suffered consecutive defeats at Stormberg, Magersfontein, and Colenso. From Buckingham Palace, a vexed Queen Victoria announced, “We are not interested in the possibilities of defeat; they do not exist.” But bold pronouncements could not obscure the truth arriving from the outer reaches of the Empire. The British had suffered their worst losses since the Crimean War a half-century earlier. All too clearly, the innate conservatism of the British military establishment had begun to take its toll. The cavalry had hitherto despised the carbine in favor of the sword—this in the dawning age of magazine-fed rifles and quick-firing guns. Few senior British officers realized that the old ways of open-order drill and carrying the day with regimental discipline and esprit de corps alone were now a prescription for outright slaughter.

At Stormberg, an attempt to wrest control of a railway junction from the Boers miscarried when the British forces were purposely misled by a native guide during a night march. Seven hundred British soldiers were missing or captured. Magersfontein was even worse. The much-vaunted Highland Brigade made an assault across an open plain in virtual parade formation against an enemy whose positions were hidden behind undiscovered barbed wire. The Boers had devised a new battlefield tactic: digging trenches dug down the front of a hill, known as the military crest, rather than at the top. By the time the attempt at Magersfontein to relieve the garrison at Kimberley was called off, 900 dead and wounded members of the Black Watch littered the battlefield.

At Colenso, Buller’s attempt to relieve Ladysmith also failed. The Irish Brigade, which was to have crossed the Tugela (“Terrible”) River three miles away, was misled by another guide, this time into a bend of the river where they were enfiladed from all sides by Boer riflemen. To make matters worse, Buller had deployed 12 field guns at Colenso without an infantry screen. In the face of withering rifle fire, the guns had to be abandoned. A handful of heroic British volunteers tried to recover them, but only two guns were brought back successfully. Casualties were relatively light, in comparison to the earlier two battles—only 150 killed. Meanwhile, Ladysmith remained under siege, and the hard-pressed British troops encircled there had begun to eat their horses and mules.

Until “Black Week,” as the English newspapers dubbed the six terrible days in mid-December, the worst of Britain’s casualties in the region had been suffered at Majuba nearly 20 years earlier, when fewer than 100 of her soldiers were killed. Now they were dying by the hundreds in battle after futile battle. These were not the usual native combatants on the fringes of the Empire—the Zulus, Pathans, or Dervishes. The Boers knew the ground far better than their foe, and they also knew the value of entrenching themselves within it. “Dig now, or they’ll dig your grave later” was their watchword. They were fiercely determined and well armed. A heavy Maxim gun firing one-inch shells, dubbed the “Pom-pom,” ranked alongside German-built Krupp howitzers, 75mm field guns, 155mm “Long Toms” firing 40-pound shrapnel shells, and the ubiquitous Mausers, effectively shredding the serried British ranks. Slowly, it dawned on the British that this was to be no “splendid little war” such as the United States had enjoyed against Spain the year before, but a grinding fight to the death against a seriously underestimated enemy.

BULLER DEMOTED; ROBERTS TAKES CHARGE

Buller was badly shaken, wiring home the despairing judgment that “I ought to let Ladysmith go.” He then sent a message to the encircled White, ordering him to burn his ciphers, fire off his ammunition, and seek whatever terms he could with the enemy “after giving me time to fortify myself.” What happened instead was a change in leadership. Buller was demoted, although he continued to command the forces in Natal, and he was told to persist in trying to lift the siege at Ladysmith. The new British commander-in-chief was retired Field Marshal Lord Frederick Roberts, 67 years old when he was recalled to active duty. Lord Horatio Herbert Kitchener—“Kitchener of Khartoum”—would serve as Roberts’ chief of staff. Roberts had already had at least one communication from Buller before he departed from London for his South African command: “Your gallant son died today. Condolences, Buller.” Such was the epistolary epitaph of the younger Roberts, who had been killed trying to save Buller’s guns at Colenso.

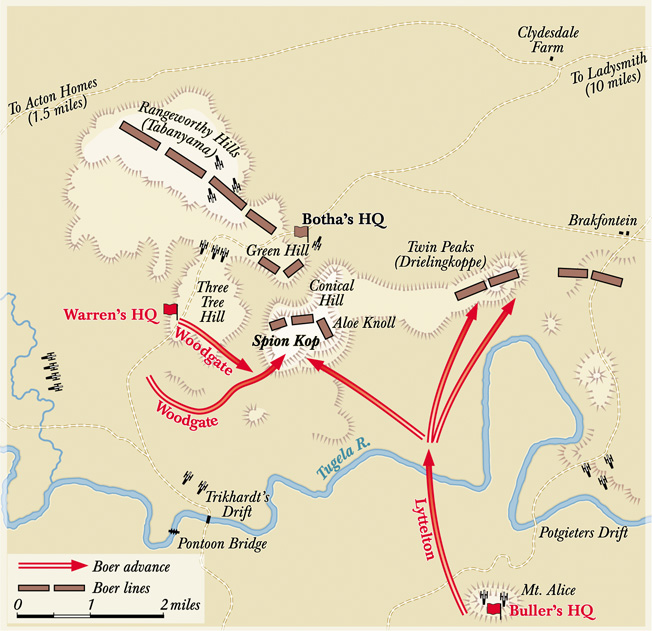

While Roberts and Kitchener were taking charge of the overall situation, Buller was reinforced in Natal by Lt. Gen. Charles Warren and the 5th Infantry Division. Warren was an odd choice to aid Buller—the older general despised him from Warren’s days as a commander in Malaya, when he had bombarded Buller with demands and complaints while Buller was serving as British adjutant general. (“For heaven’s sake, leave us alone,” Buller had finally told Warren, in utter exasperation.) Now he gave Warren the task of crossing the Tugela River and moving on the Boer right at Tabanyama Ridge, 12 miles southwest of Ladysmith. Meanwhile, Buller would attack the enemy center at Potgeiter’s Drift. Once through the hills beyond the river, the two English columns would reunite for a last-ditch drive across the open plains to Ladysmith.

Warren, who had spent much of his career excavating historical sites in Palestine, had grown accustomed to the painstaking pace of archaeology. Given two-thirds of Buller’s ponderous army to command—11,000 infantrymen, 2,200 cavalry, and 36 field guns—he took the better part of nine days to reach Trichardt’s Drift on the Tugela, the jumping-off point for the coordinated attack. Another day was wasted ferrying guns and supplies across the river.

The Boers, with their crack contingent of scouts, knew every move the British were making. They responded by strengthening their defenses and shifting troops from the siege of Ladysmith to the line of hills overlooking the Tugela. Louis Botha was dispatched to take command of the burghers’ defense. Reasoning correctly that the British always attacked head-on, Botha paid particular attention to the large hill in the center of his line—Spion Kop. Aptly named, the boulder-bedecked “Spy Hill” rose to a height of over 1,400 feet, the centerpiece of several hills that commanded the veldt and the approaches to Ladysmith north of the river. Sixty years earlier, the first hardy voortrekkers had climbed its prominence during the Great Trek northward. Then, as now, they were fleeing the British, but this time they were better armed and better fortified. When the time came, they would be ready.

On January 20, Warren finally attacked the Boer positions on Tabanyama Ridge. The khaki-clad British troops managed to carry a hill or two before halting amid a cyclone of Mauser fire. Ahead of them lay a thousand yards of open grassland, more than enough distance to give them pause, particularly in the face of the quick-firing Boers. Warren wanted to conduct a leisurely bombardment before making another attack, but he was overruled by Buller, who ordered him to attack again immediately. The order came with an explicit “or else.” Buller threatened to call off the entire campaign if Warren did not do as he was told. Thinking quickly—or at least as quickly as he was capable of thinking—Warren suggested an alternative plan. Instead of renewing his attack on the Boer right, he would move on Spion Kop. Buller was not appeased. “Of course you must take Spion Kop,” he told his hated subordinate, but he neglected to supply him with any new troops or ideas on how to accomplish it. It was going to be left to Warren alone, much to the detriment of the men he commanded.

BRITISH TAKE SPION KOP

Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Thorneycroft, commanding a contingent of mounted infantry, was selected to spearhead Warren’s attack. On the evening of January 23, Thorneycroft and his men surreptitiously climbed the slope on the near side of Spion Kop and seized the sere moonscape of the summit, a flash of Lee-Enfields and total surprise winning them the strategic position with very few casualties. Three cheers went up for Queen Victoria—the prearranged signal for success—and the way to Ladysmith lay before them at last. But first they must hold on to their prize. Maj. Gen. Edward Woodgate, senior commander on the hill, quickly got the men busy digging trenches in the moonlight, before the eagle-eyed Boers could zero in on their position. He sent a note to Warren informing him of the success, adding that he expected that Spion Kop could be “held till Doomsday against all comers.”

The hill had been shrouded in fog, and when the mists slowly cleared with the dawn it became all too evident to the British that they did not hold the hilltop at all, but only a small, acre-wide plateau ringed on three sides by higher hills that afforded the enemy perfectly sited, boulder-protected firing positions. The Boers, who had watched the leisurely progress of the British with tight-lipped satisfaction, were even now creeping into those positions. Botha ordered his men to retake the position before the British had time to move up their own heavy guns. His burghers quickly poured devastating salvos into the densely packed British troops. The Englishmen, hunkering down in shallow trenches in a confined space comparable in size and dimension to Trafalgar Square, had little cover. The Boers’ artillery, signaled by heliograph, directed intense fire at Spion Kop from the surrounding hills. Shells rained down on the British position at the rate of 10 per minute. Meanwhile, the British heliograph had been knocked out, and they had no comparable artillery support from their own crack gunners. The soldiers atop Spion Kop were on their own.

THE MASSACRE BEGINS

Responding to Botha’s call for reinforcements, Commandant Henrik Prinsloo led his 88-man Carolina Commando onto Aloe Knoll, 400 yards east of the British position. From there, Prinsloo’s marksmen unleashed a deadly fire on the unsuspecting men of the Lancashire Fusiliers, who were on the extreme right flank of the British trench. The Khakis, as the Boers called them, never knew what hit them. Seventy were later found lying dead with bullet holes in the right side of their heads—they had not even had time to turn around. Also struck dead was their commanding general, Woodgate, who fell mortally wounded with a shell splinter above his right eye. His replacement, Colonel Malby Crofton, sent a hasty message down the hill to Warren: “Reinforce at once or all lost. General dead.” Warren, unhelpful as always, signaled back: “You must hold on to the last. No surrender.” His entire career depended on it.

Grimly, the British held on to the 400-yard-wide battlefield. No one on the British side had given much thought to what to do after seizing Spion Kop; asked what his force should do next, Buller had answered dogmatically, “It has got to stay there.” It stayed there all right, stolid and immobile, absorbing a horrific beating. Many of the officers were killed, victims of the Victorian-era code that prohibited a gentleman from taking cover under fire. The men in the ranks, less hidebound and conventional, squirmed into every square inch of cover they could find in the rocky topsoil. It did little good. Boer artillery shells dismembered entire files of soldiers where they lay, while those foolish enough to raise their heads off the ground were immediately shot dead by enemy snipers.

On the command level, all was chaos. At one time or another, four separate senior British officers believed themselves to be in command. In his only direct action of the day, Buller recommended to Warren that he “put some really good hard fighting man in command on the top. I suggest Thorneycroft.” Warren, glad for any assistance, promoted Throneycroft to brigadier general and gave him operational control of the battle. Thorneycroft’s first move was to countermand an attempt by the Lancashire Fusiliers to surrender to the Boers who were bedeviling them. “Take your men back to hell, sir!” Thorneycroft roared at the Boer officer who had approached to accept the surrender under a white flag. “I allow no surrender.” Shamefaced, some of the Fusiliers skulked back to their own lines; others, having no wish to commit state-sanctioned suicide, dashed into the Boer lines and surrendered.

Returning to the forefront now was Winston Churchill, who besides bearing journalist’s credentials also carried a new commission in the South African Light Horse given to him by Buller after Churchill’s extraordinary escape from a Boer prison (see sidebar). Churchill climbed Spion Kop and assayed the scene for himself, conveying it later in words that would find their echo on the Western Front in Europe 15 years later: “Corpses lay here and there. Many of the wounds were of a horrible nature. The splinters and fragments of the shells had torn and mutilated them. The shallow trenches were choked with dead and wounded.” As Churchill climbed and re-climbed the hill, ferrying messages from Buller’s camp, he was “continually under shell and rifle fire and once the feather in my hat was cut through by a bullet. But in then end I came serenely through.”

Little else was serene on the bloody hilltop. Boers and Britons faced each other across a landscape of butchered bodies and heaped wreckage. Battalions were hopelessly intermixed. Messages between the hilltop and Buller, four miles away, were sporadic and confused, and several messengers fell dead with vital information unread in their hands. No one below knew the situation above. Some officers thought the hilltop overcrowded, while others thought there was a vital need for reinforcements. Thorneycroft, for his part, seemed dazed and utterly exhausted. He sent another message to Warren, from whom he had not heard in five long hours. “The troops which marched up here last night are quite done in,” he reported. “They have had no water, and ammunition is running short. It is impossible to permanently hold this place so long as the enemy’s guns can play on the hill. It is all I can do to hold my own. If casualties go on at the present rate I shall barely hold out the night.”

THORNEYCROFT ORDERS A TOTAL WTHDRAWAL

After a hurried conference with Crofton and Lt. Col. Ernest Cooke of the newly arrived Scottish Rifles, Thorneycroft ordered a total withdrawal. A last-second message from Warren promising that help was on the way fell on deaf ears. “Better six good battalions safely down the hill than a bloody mop-up in the morning,” Thorneycroft said. “I’ve done all I can, and I’m not going back.” In vain, the upstart Lieutenant Churchill argued the point, and the retreat began. Abandoning the hard-won hill, the British survivors met their reinforcements massing at the bottom, en route to assist them in consolidating their position. It was too late—surely the Boers had already retaken the hilltop—and Thorneycroft turned these troops around as well. Survivors and reinforcements alike trudged back down the hillside.

Unknown to the British, the Boers had also lost the will to fight, and they too had begun to melt away, in part because they were startled by a sudden move across the Tugela by the King’s Royal Rifle Corps east of Spion Kop at Acton Homes. Barely a handful of Boers remained on hand to threaten the British. The hilltop so fiercely contested at such human cost was discovered by two joyful Boer scouts to be empty. After the British had spent 16 days and suffered almost 2,000 casualties on the campaign, Botha’s burghers were atop Spion Kop once more as if nothing had happened. Only the three-deep piles of British dead remained to dispel that illusion. In soldierly admiration, a Boer doctor examined the human carnage and said, “We Boers would not, could not, suffer like this.”

Botha, returning to the hilltop the next morning, beheld “a gruesome, sickening, hideous picture.” Some 400 dead British soldiers lay sprawled in a shallow trench that would serve double-duty as their grave; another 1,400 were wounded or in captivity. Boer losses were considerably lower—58 dead and 140 wounded, including 55 of Prinsloo’s 88 hard-fighting Carolina Commando. Botha sent a humble telegram back to President Kruger: “Battle over and by the grace of a God a magnificent victory for us. The enemy driven out of their positions and their losses are great. It breaks my heart to say that so many of our gallant heroes have also been killed or wounded. It is incredible that such a small handful of men, with the help of the Most High, could fight and withstand the mighty Britain.”

BRITISH NUMBERS FINALLY PREVAIL

Finally, with his artillery in full support, Buller managed to throw a pontoon bridge across the Tugela, and overwhelming British infantry turned the key in the Ladysmith lock, seizing the last remaining hilltop barring their way. The siege of the British forces there had lasted 118 days. It was lifted on February 27, 1900, ironically the anniversary of the defeat the British had suffered at Majuba 19 years earlier.

Lord Roberts now took center stage as overall commander after the protracted drama of Ladysmith. His forces totaled over 200,000 against 88,000 Boers. The latter began to abandon the Transvaal, retreating into the hinterland in another Great Trek. Churchill, as ever marching to the sound of the guns, carried by bicycle a crucial dispatch to Roberts through a Johannesburg still occupied by Boers; the slightest challenge by a wary burgher might have caused him to be executed as a spy. His audacity endeared him to yet another commander-in-chief. As the Boers withdrew to the east, yielding large parts of the Transvaal, Roberts allowed Churchill to enter Pretoria at the front of the column. One of Churchill’s singular pleasures was to hoist the Union Jack over the place where he had been held as a prisoner of war.

Other combat followed in the form of desultory running fights with the Boers who, despite having been defeated in the field, refused to capitulate. Raiding deep into British territory, the Boers fought for two more years in the newly developed irregular fashion called guerrilla warfare—another dubious innovation bestowed on the newborn century. Buller, for his part, had managed no such innovative thinking. He could have followed up the British cavalry’s success at Acton Homes and exploited its mobility to outflank the Boers and open the road to Ladysmith, but he could not get his main force there quickly enough, and thus had to fight a battle that grossly favored the enemy. Churchill’s biting description of Buller’s traveling camp was apt: “Within striking distance of a mobile enemy whom we wish to circumvent, every soldier has canvas shelter. Rapidity of movement is out of the question. It is poor economy to let a soldier live well for three days at the expense of killing him on the fourth.”

The laborious and cumbersome movements doomed hundreds of regular British soldiers to a Mauser bullet in the head at Spion Kop, and the hidebound conventions of the Victorian era—sneering at the use of cover and demanding an unflappable hauteur in the presence of the enemy—left their bloody epitaph stitched across the chests of their gentlemanly commanders. Few British survivors of Spion Kop would have disputed the mordant words of Manchester Guardiancorrespondent John Atkins, who was there that day and later summed up the battle as “that acre of massacre, that complete shambles.” Indeed it was.