Category: Fieldcraft

Some hopefully useful info

Huh!

“It” was about 2′ long or so, big for its breed, and facing away from me where I couldn’t see the sinister smile concealing its fangs. I’d seen plenty of copperheads before and knew one this close to the house had pretty much signed its own death warrant. I’d seen him — though not until I was waaay too close, but I might not the next time.

Multitasking Geometry

Still carrying on my business call, I pondered my options. To this point, I had only ever killed copperheads with a knife. A dangerous business, but geometrically logical: Intersecting a line (the snake) with another line (the blade of my Cold Steel Tanto) was easier than intersecting a line (the snake) with a point (read: bullet). To be fair, I hadn’t actually graphed all this out the first time I did it.

Slither At Me, Bro

I was walking back to the car one night in the national forest after showing off my camp cooking skills to a girl when a particularly aggressive copperhead showed up in the halo of my Coleman lantern and headed my way. I snatched the Cold Steel out of its scabbard and decapitated the serpent with a swipe before I realized I had just gotten into a knife fight with a venomous snake. I won, but was a bit shaky about it. Then I justified it by the angles, and the feeling turned to “slither at me, bro.”

I’d done it again, also in the dark, when my friend I was following down a trail nearly stepped on one. This snake took two hits to kill, but kill him I did.

This time, though, with a hand holding the phone to my ear, I knew I didn’t have the range of motion to make it work with a blade, and trying meant I would almost certainly get bitten. Inexplicably, I completely ignored the shed in front of me, with its hoes, rakes and shovels, as well as an entire barn next to me filled with all the implements previously used to work the land. Instead, I fixated on something entirely new: My .22 suppressor.

SBD

The paperwork had just cleared for my first silencer. Even better, I had a new titanium-framed 1911 freshly built on a recent trip to Novak’s, along with its matching .22 conversion. My plan was simple: Walk into the house, carrying on the conversation with el presidente, assemble the conversion onto my new pistol, screw on the can, walk outside — doing my best 007 impression — and pop, Bond’s your uncle. With the low report of the suppressed shot, it wouldn’t be heard through the phone and there would be no interruption to the call, which was important. As I said, I didn’t really know this man, and I wanted to impress him.

All went well until first contact; I walked up behind the snake, lined him up over those Novak LoMounts and pressed the trigger. The pistol made a gentle “pop,” and the earth exploded beneath the copperhead as the bullet nicked him. He warped around at the speed of heat, immediately striking and striking again while I desperately crab-walked backward, one-handing shots at him while he, equally fervent, continued trying to kill me. Pop. Pop. PopPopPop. Pop.

End Times

The end of the mag was near, and my options with it, when I finally anchored him with a solid head shot. By now, the president had long since gone silent.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I’m sure you’re wondering what that was.”

“It sounded like a .22 rifle,” he responded drily.

“Close. It was a suppressed pistol. I, uh, had to kill a pit viper.”

I’ll never really know whether he believed me in that moment or not; I only know he asked for a photo of me, the snake and the gun.

Which I sent. He and I are friends to this day, and I like to think that near-lethal phone call cemented the relationship. Of course, I may just like to think that.

When it comes to venturing into the outdoors to either go camping, hiking, hunting, or to snap some dope pics for the ‘Gram (Instagram), we as gun owners like to debate the merits of firearms against apex predators. Whether it is the local meth head from the trailer park “cooking” in the State Park or a more likely encounter of a bear in the woods. What is your best defense?… A sidearm like a big-bore revolver or is it “Bear-Grade” pepper spray. If you have resolved to carrying a revolver in bear country, let’s take a look back at some of the more entertaining options to come from the firearm industry in the Revolvers vs Bears debate.

Wheelgun Wednesday @ TFB:

- Wheelgun Wednesday: What’s Your Go-To Barrel Length For Revolvers?

- Wheelgun Wednesday: Current Chinese Police Revolvers – NRP9 and ZLS05

- Wheelgun Wednesday: Smith & Wesson Classic – What’s Old is New Again

- Wheelgun Wednesday: ‘Dangerous’ Saturday Night Special – Why Illegal?

REVOLVERS VS BEARS – IS A GUN YOUR BEST OPTION?

For those of us who watch TFBTV (make sure to Like & Subscribe), you may remember that James Reeves has covered the debate of Revolvers vs Bears quite a bit over the years. He dropped 3 different videos over a 2 year period debating whether you should use a .44 Magnum, 10mm, or simply bear spray.

- TFBTV – Bears vs Handguns: Defending Yourself in Bear Country

- TFBTV – Guns & Bears: Glock 10mm or .44 Magnum for Protection?

- TFBTV – So… Are Guns or Bear Spray More Effective Against Grizzlies? (Guns vs. Bears, Episode 3)

I take James’ opinion on this matter very seriously because where I might have 30+ more years of experience in hunting (including black bears – generally passive), James on the other hand has hiked probably 1/2 of our National Parks with his wife over the years and encountered innumerable brown bears (significantly more aggressive temperament). His scholarly research and anecdotal experiences have led him to believe that it’s almost a dead tie for what you should be using (guns versus bear spray), but some recent research tips the scale in favor of firearms. So, with that intelligent, cogent analysis from our in-house lawyer, let’s discuss completely stupid guns that were discontinued that could have been used in the past in the Revolvers vs Bears debate.

REVOLVERS VS BEARS – IS A GUN YOUR BEST OPTION?

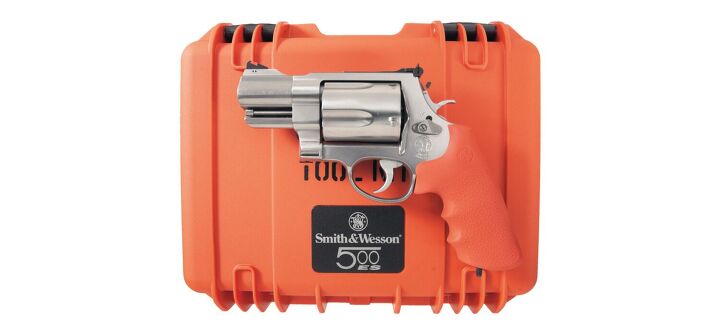

There was a small window of time in the late ’90s and early 2000s where Smith & Wesson thought it was a rad idea to make “Emergency Survival Tool Kits.” You got a Pelican-style case full of goodies to fool yourself into believing you were Bear Grylls, but with less knowledge than a cub scout. You got such marketing hype survival items as a Mylar space blanket, a whistle, a Smith & Wesson Extreme Ops folding knife, and a “Bear Attacks of The Century” survival book just to elicit some pucker factor. You also got a deafening, blinding, and atrocious to shoot Model 500 with a 2 3/4″ barrel (talk about “riding the lightning”).

- Smith & Wesson Model 500 Revolver in .500 S&W Magnum – 2 3/4″ Barrel with Bright Orange Hogue Grips

- (1) Orange Waterproof Storm Case

- (1) Blast Match Firestarter

- (3) Wetfire Fire Starters

- (1) Saber Cut Saw with Nylon Sheath

- (1) Jet Scream Whistle

- (1) Star Flash Signal Mirror

- (1) Polaris Compass

- (2) MPI Mylar Space Emergency Blankets

- (1) Smith & Wesson Extreme Ops Liner Lock Folding Knife with Nylon Sheath

- (1) “Bear Attacks of The Century” Survival Book

- (1) Master Lock

- (1) Set of Keys for Internal Lock

- (1) Shipping Box Numbered to the Gun and Papers

Smith & Wesson Model 500 (Emergency Survival Tool Kit) .500 S&W Magnum

Anybody who questioned their manhood ran out and bought these because it was like Smith & Wesson issuing free “Man Cards” to anyone who owned one (at the modest fee of $800 – $1,000 and some broken wrists). If you were going with the family to Alaska to drink beer from a boat spot brown bears, this revolver was a MUST. This revolver’s fast cult following brought a 2nd iteration for us to feast our eyes on – the Smith & Wesson Model 460 (Emergency Survival Tool Kit) .460 S&W Magnum.

- Smith & Wesson Model 460 Revolver in .460 S&W Magnum – 2 3/4″ Barrel with Bright Yellow Hogue Grips

- (1) Yellow Waterproof Storm Case

- (1) Blast Match Firestarter

- (3) Wetfire Fire Starters

- (1) Saber Cut Saw with Nylon Sheath

- (1) Jet Scream Whistle

- (1) Star Flash Signal Mirror

- (1) Polaris Compass

- (2) MPI Mylar Space Emergency Blankets

- (1) Smith & Wesson Extreme Ops Liner Lock Folding Knife with Nylon Sheath

- (1) “Bear Attacks of The Century” Survival Book

- (1) Master Lock

- (1) Set of Keys for Internal Lock

- (1) Shipping Box Numbered to the Gun and Papers

Smith & Wesson Model 460 (Emergency Survival Tool Kit) .460 S&W Magnum

To not confuse those who were basking in the glow of another man’s manliness, this new variation in .460 S&W Magnum had all bright yellow accouterments. You got a nearly identical kit of survival tools as well. This revolver also became legendary and scarce from the time it was initially produced until it was eventually discontinued.

Right when all the glow and buzz of Smith & Wesson’s “Emergency Survival Tool Kits” was about to burn out, Taurus decided to jump on the bandwagon. They came out with some “First 24” survival kits alluding to being able to survive those first 24 hours alone before help can come save you in a Bear Grylls-esque survival situation (cue Google searches for “is that a psilocybin mushroom, or an edible one”). These Taurus First 24 kits were not meant to be directed at dropping 1,300 Lb grizzly bears, but that didn’t stop people on the internet from entertaining the thought of using a .357 Magnum or .45 Long Colt to do so.

- Taurus 617 (X-COAT Black) .357 Mag | Taurus Judge (XCOAT Tan) .45 LC/.410 Gauge

- AimPro Tactical Enhancement Package

- I-Series SKB Case (Black or FDE)

- (2) HKS Speed Loader or (2) Bianchi Speed Strips

- CRKT Sting (Black or FDE)

- Brite-Strike® ELPI (Black or FDE)

- Brite-Strike® APALS (green/red/white) – 1 each color

- Hogue Inc. Mono-grip

- Zippo Fire Starter kit

- Energizer batteries (AA)

- Slim Line caddy for batteries

- 550 Para cord bundle (20ft)

- Survival blanket

- Suunto Compass

- MSRP $1399 (Model 617) | MSRP $1,499 (Judge)

Taurus “First 24” Kits – Model 617 .357 Magnum & Judge .45 LC/.410 Gauge

REVOLVERS VS BEARS – SO, WHAT’S NEXT?

Now, if you are able to find either of the Smith & Wesson “Emergency Survival Tool Kits” they sell for $2,000+ online and at auctions. Even the more affordable Taurus “First 24” kits sell for $1,000+ (if you can actually find one). So, I beg the question: what is next? Do you think we’ll ever see a resurgence of these revolvers? Would Ruger throw their hat in the bear survival ring with a cringy kit? As always, let us know all of your thoughts in the Comments below! Also, read on further for an NSFW gun counter story. We always appreciate your feedback.

[NSFW] Revolvers vs Bears: Selling Revolvers for Bear Defense – True Story from the Gun Counter

Alright, now that all the people with delicate sensibilities have left the article, let me share a crass, but hilarious story from my years managing a gun store (which is still my day job).

[Scene] – I am standing by the gun counter with an old regular of mine, Richard, shooting the breeze about nothing. Richard is a tiny man, a veteran, bent over, old, looks like hell, but he lived one hell of a life; the stuff that should be put in patriotic movies.

A young kid comes in strutting through the store looking for a revolver. He needs a BIG revolver as he states because he’s going huntin’ in grizz country. I smile as Richard shakes his head disapprovingly. I can only imagine this young kid is looking for some kind of rite of passage to come into his own… be a man… figure out who he is in this life. I see myself in him, but I’ve got 15+ years on him.

This young man – 110 Lb sopping weight, maybe – slides his way down the gun counter towards where Richard and I are still BS-ing about nothing. The young man prompts another co-worker of mine to pull out that massive one, right thar (inject as much Northwoods, gravy inflection into that as you can). It is magnificent – a Smith & Wesson 500 with an 8 3/8″ barrel. It has a finish so bright you can see your reflection.

Richard, once again, is disapprovingly shaking his head. The young man starts groping that huge, magnificent revolver like he’s a TSA worker at the airport. He is simply in awe of it. Finally, Richard can’t take it anymore. He gruffs under his breath, “That’ll never do.” The young man whirls his gaze at this feeble, small, old man. Although his stature was small, Richard had violent eyes; someone you didn’t mess with it. The young man gave Richard his undivided attention: “Why not?!”

Richard elaborates, “The front sight… it’s all wrong… you need to shave that clear off.”

The young man is utterly perplexed. He concerningly asks, “But why would I do that?…”

“Then,” Richard says with a smile, “when that grizzly bear shoves that revolver up your a$$ before he eats you, it’ll hurt less going in.”

This young man was ghost white, scared, confused, and not sure what to make of the situation. Finally, I couldn’t keep it in anymore. I busted a gut laughing so hard that I started crying. Richard joined in in uncontrollable laughter. So much so, that he fell over and I had to help him stand back up.

This young man finally cracked a nervous smile and laughed, too. He stayed in our store for over an hour as we discussed ballistics, Stopping Pow-Ah, holster options, bear spray, and all manner of things. He did eventually buy a revolver, Richard then recommended some 60-grit sandpaper, we laughed again, and the kid ran off happy with his purchase.

Remember… in the struggle of Revolvers vs Bears some of your greatest allies are avoidance, situational awareness, and lastly swift, violent action. Similar to any self-defense situation.