Category: Allies

Ians Top 5 SMGs

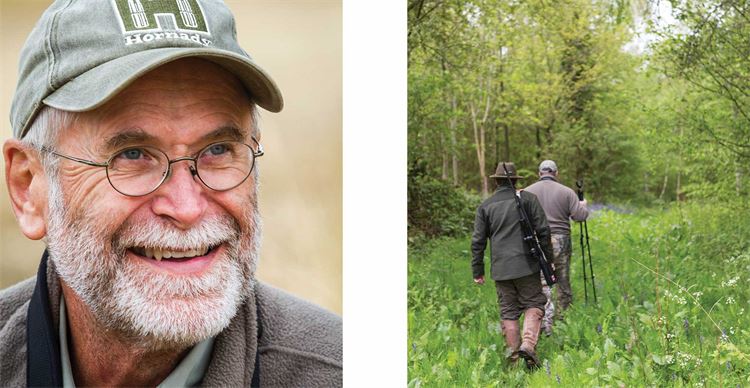

President of Hornady Ammunition, Steve Hornady, shares his views on the perfect all-round calibre for deer stalking in the UK.

Ihope it goes bronze,” said Steve Hornady as he sat outside a thatched 16th Century inn in Hampshire at the beginning of the roe rut. He had just returned from an early morning stalk that had yielded a handsome buck that had been called in with a beech leaf. Great start to the day, especially as it was shot using a bullet with his name on.

Based in Nebraska, Steve has worked in the Hornady business his entire life. This means he has been involved in ammunition development and design for over 60 years. He also has an enviable trophy room, having hunted all over the world for just about every species you can think of. It was apparent from Steve’s excitable rendition of the morning’s stalk that hunting is a big part of his life.

“The hunting industry is the best business for me to work in for the recreational use of the products my company creates. I get to see first hand how our products perform in the field,” he explained. During Steve’s career, he has been involved in the development of some of the most popular hunting calibres used today, including the .17 HMR, .204 Ruger, 6.5 Creedmoor and the .220 Swift. He has also reintroduced a number of the larger Nitro Express big game calibres that had fallen into obscurity such as the 450/400, .450 and the hugely popular .470, making them more affordable and readily available. Employing more than 300 staff at the Hornady headquarters in Nebraska, the company produces millions of rounds every month in nearly every commercially available hunting calibre. In short, there is little Steve does not know about ammunition design or its application in the field.

With this encyclopedic knowledge, we were keen to hear his thoughts on the most suitable all-round calibre for UK hunting. “We all know that the perfect all-rounder is a neat concept but does not actually exist,” he shrugged, adding: “A heat-seeking bullet that holds together at point blank, expands on the other side of the planet, breaks bones cleanly and opens on lungs is the holy grail, but sadly impossible.” Clearly, allowances have to be made depending on the task in hand. “It is possible to have a perfect bullet for one job, but not all of them,” he added. “Interestingly, the UK has similar circumstances to those I have found in Africa. Leaving aside the really big stuff, there is large game like blue wildebeest but also small game like duiker and springbok. It is likely you may want to hunt both with the same rifle. The same applies in the UK, where you may want to use the same rifle for large red stags and miniature muntjac.”

Steve explained the basic physics and an important concept that many new stalkers fail to grasp: “If a muntjac walks out at close range, a heavier bullet is better than a light one. Travelling at a slower velocity, it will expand less violently and cause less meat damage. However, to take a fallow buck at 300m in a stubble field, a faster, flatter, harder-hitting round is what is needed.” So therein lies the problem, not just in the UK but the world over.

Given that Hornady is one of the best selling brands of ammunition in the UK, Steve knows which are the most popular hunting rounds used on our shores. And he is fascinated that British hunters are still in love with the old stalwart calibres, some of which were designed more than 100 years ago. “I am not saying that there is anything wrong with a .243, .308 .270, 6.5×55 or a .30-06, but newer cartridge designs have improved how we ignite and burn modern powders. The core technology is fundamentally the same, but to use an automotive analogy, we are using an old chassis with a new engine and better wheels. Theoretically, this makes it a better car.” Old cartridges will be popular forever, but the fact remains that there have been modern improvements that have taken cartridges forward and improved accuracy, efficiency and uniformity.

Having grasped the basics of the UK’s firearms licensing system, which makes acquiring rifles and ammunition of different calibres far more difficult than it is the US, Steve agreed to pick a calibre as the most suitable for hunting in the UK, chosen from the most popular calibres sold here. As an interesting aside, had he been able to pick any round for the UK, he would have opted for the 6.5 Creedmoor. This is due to its impressive ballistic co-efficient (flies flatter with less drag), fast powder ignition, short action and low recoil. With bullets from 120 to 140gr, it is a near perfect fit for all UK species. His caveat for the calibre was that if tackling enormous red stags it would be worth considering a less frangible, harder copper alloy bullet to guarantee penetration to the vitals.

From the most readily available calibres in the UK, however, it came as no major surprise that Steve picked the trusty .308 Winchester as the calibre that would be able to comfortably deal with any task put before it. To Steve, this old faithful represents a versatile and great option for all UK deer species. Developed in 1952, it has seen extensive service in both the commercial hunting and military world with its doppelganger designation of 7.62mm NATO. A short, relatively fat case helps efficient and uniform powder ignition. The squarer shoulders help to use headspace in the chamber more effectively. All of these factors help the .308 deliver sniper-type accuracy, shooting bullet weights from 150 to 180gr with many loads in between. Even when tackling the smaller UK species, Steve pointed out that the combination of the .308’s modest velocity (approx 2,500 – 2,800fps), and a less frangible bullet head such as an Interlock or Interbond, will not unreasonably damage a deer carcass. One of the other advantages is availability. Indeed, factory loaded cartridges are guaranteed in almost every gun shop across the land.

With regards to some of the other popular calibres for deer stalking in the UK, Steve had some interesting things to say, particularly about the .243 Win, which, according to a recent survey of British Deer Society members, accounts for 70 per cent of all deer rifles in the UK. Launched in 1955, the .243 Win is simply a .308 case necked down to accommodate the .243 bullet.

The calibre was designed as a vermin calibre in the States, with the optimal bullet weights being 70 to 85gr. It is possible to load heavier bullets into the cartridge, up to 105gr, making them more suitable for deer. In fact, it is only legal to shoot deer (apart from roe) in Scotland with bullets of 100gr or heavier at over 2,450fps. Steve agreed that the .243 is a highly versatile round, but only in the hands of a competent shooter. “There is little margin of error on larger species,” he said. “For foxes, roe, muntjac and Chinese water deer, you couldn’t get a better cartridge than a .243 as it is flat flying and accurate, but for larger species, a slight miscalculation on the shot is likely to lead to wounding issues.”

We were interested in Steve’s thoughts on the .270 Win as it was once a very popular calibre in the UK and was widely used by the Forestry Commission in the UK and Scotland. Although an effective and relatively accurate round, Steve feels that this long action calibre is overly aggressive, having witnessed some major carcass and meat damage resulting from the round’s high velocities.

As a necked-down version of the 30-06 Springfield, the 130gr bullet has a muzzle velocity of over 3,000 fps. This means anything shot at closer ranges (out to 150 yards) is likely to suffer from explosive bullet trauma. There is also a significant amount of recoil from this cartridge, which newer calibres have been designed to overcome. It is a great long-range plains game calibre, but there are simply better choices out there now.

The .270’s bigger brother, the 30-06 Springfield, designed in 1906, is an old favourite of Steve’s, although it is, he says, too much gun for the UK. It will handle red stags with ease with its 150 – 180gr optimal bullet weight, but that extra speed and energy equates to unnecessary meat damage.

Steve’s final comment was characteristically to the point: “Why don’t you Brits just do what we do and buy more guns? Most American hunters have a different rifle and specific load for each species they hunt.

That way, you get the best out of of each calibre and don’t ask too much of every load. It might also be worth your while dabbling in some of the new, more efficient 21st century calibres. Lobby the police and educate them about these new designations as they should be accepted as part of the normal hunting scenery.”

UK Calibre Law

England & Wales

For muntjac and Chinese water deer only, a rifle with a minimum calibre of not less than .220″ and muzzle energy of not less than 1,000 ft/lb and a bullet weight of not less than 50gr may be used. For all deer of any species, a minimum calibre of .240 and minimum muzzle energy of 1,700 ft lb is the legal requirement.

Scotland

For roe deer, the bullet must weigh at least 50gr AND have a minimum muzzle velocity of 2,450 fps AND a minimum muzzle energy of 1,000 ft lb. For all deer of any species, the bullet must weigh at least 100gr AND have a minimum muzzle velocity of 2,450 fps AND a minimum muzzle energy of 1,750 ft lb.