Category: Allies

Attack drones credit: Shutterstock

Has the IDF learned the lessons of the wars in Ukraine and Syria in which FPV (first person view) attack drones changed the face of the campaigns? The Ministry of Defense Department of Production and Procurement is currently publishing the terms of a tender to procure 5,000 FPV drones from Israeli companies, which are usually used in drone races.

But in war these drones can squeeze through the narrow opening of an armored personnel carrier or tank, crashing accurately and fatally into a group of soldiers in an ambush, or homing in on the tail of an enemy drone. FPV drones carry much smaller amounts of explosives than UAVs, but the ability to quickly crash into weapons or fuel depots can increase collateral damage by several dozen times.

Unlike the standard off-the-shelf drones that the IDF already uses today, manufactured by companies such as DJI or China’s Autel, FPV drones cannot stay in the air for long, and are not autonomous, but are fully controlled by the pilot, who must be skilled with remote control of the drone, which can easily crash to the ground, if the pilot loses control. Therefore, learning skills and many hours of training are required, involving increased costs and greater selectivity in the number of soldiers who can operate them.

The tender could expand

The estimated price of an FPV drone is lower than an autonomous drone, costing up to NIS 10,000 each at most, but it is possible that the Ministry of Defense will choose the cheapest alternative, drones that cost NIS 3,000. In such a case, the tender is expected to cost the Ministry of Defense no more than NIS 35 million, but it may also be expanded to 10,000 drones, and allow entry of a second supplier, so the cost could rise to over NIS 70 million. Senior figures in the drone industry are counting on expanding the tender to 20,000 drones in the long term.

Globes reported last year that the tender would be issued in August. However, the nature of the tender has changed, and will now it focuses on attack drones only. According to specifications sent to suppliers, this is a small number of drones. The tender requires the immediate procurement of 5,000 drones, which experts say is insufficient. For comparison, Ukraine manufactured 2.2 million FPV drones last year alone.

Others in the drone industry also warn about the issue of security information in the tender, since the required components are analog, and can be easily hacked and located by enemy forces. For example, the video transmitter detailed in the tender is manufactured by Chinese company Team BlackSheep based in Hong Kong.

The industry has been surprised by the unusually detailed requirement of the procurement administration to include items manufactured by certain companies, let alone a company from China. The Ministry of Defense opposed the move, after encouraging the development of a digital communications infrastructure for drones. Cost considerations are apparently behind the request for Chinese equipment, even though Israeli companies know how to offer an alternative communications solution, with a price difference of tens of dollars per unit.

Bat versus Rooster

So far, about 25 Israeli drone suppliers that work with the Ministry of Defense have registered for the tender, including Xtend, Robotican, Tehiru, CopterPix and Dronix. The favorite to win the tender is considered to be The Bat, attack drone made by Petah Tikva-based Dronix. The Bat, a four-bladed drone, can fly a distance of up to 5 kilometers or up to 15 minutes, wth a payload of a thermal camera and explosive charge weighing up to 2.7 kilograms.

Another favorite is Xtend from Ramat HaHayal in Tel Aviv which has already equipped the IDF and the US Pentagon with its Scorpio attack drones. Xtend achieved the feat by becoming the first company in the US to receive approval to operate an armed suicide drone. The company has an existing training and feasibility demonstration system to reduce the training time for drone pilots – from months to a few hours.

However, winning the Israeli tender will require it to remove the secure digital communications infrastructure it developed and install analog communications instead, based on the Chinese equipment requested by the Ministry of Defense.

Another company that bid for the tender is Tehiru, which has made two proposals; one taking into account the analog communications dictated by the tender, and the other with encrypted digital communications in an Israeli format. Another Israeli drone in the category is Omer-based Robotican’s Rooster. The drone can carry 300 grams of cargo and hover for up to 12 minutes at a time, and Sapir also intends to compete by downgrading its advanced drone, the Viper 300, which can fly 5 kilometers and stay in the air for 20 minutes, to meet the tender’s terms.

The tender requires the companies to not only provide the drones, but also travel bags, ground stations, a training systems, service and maintenance, and the establishment of a local production and assembly line. Some Israeli companies, such as Xtend and Dronix, already own such facilities. The deadline for submitting bids was last week, and a supplier conference for the 25 bidders was supposed to take place on Monday of this week, but was postponed for an unknown reason.

No response was forthcoming from the Ministry of Defense and any of the bidders.

Creating the Sherman FIREFLY

Are Revolvers Obsolete?

His buddies on the bench are not amused by this! Grumpy

You People Are Paranoid!

A ship is a fool to fight a fort ! – Lord Nelson

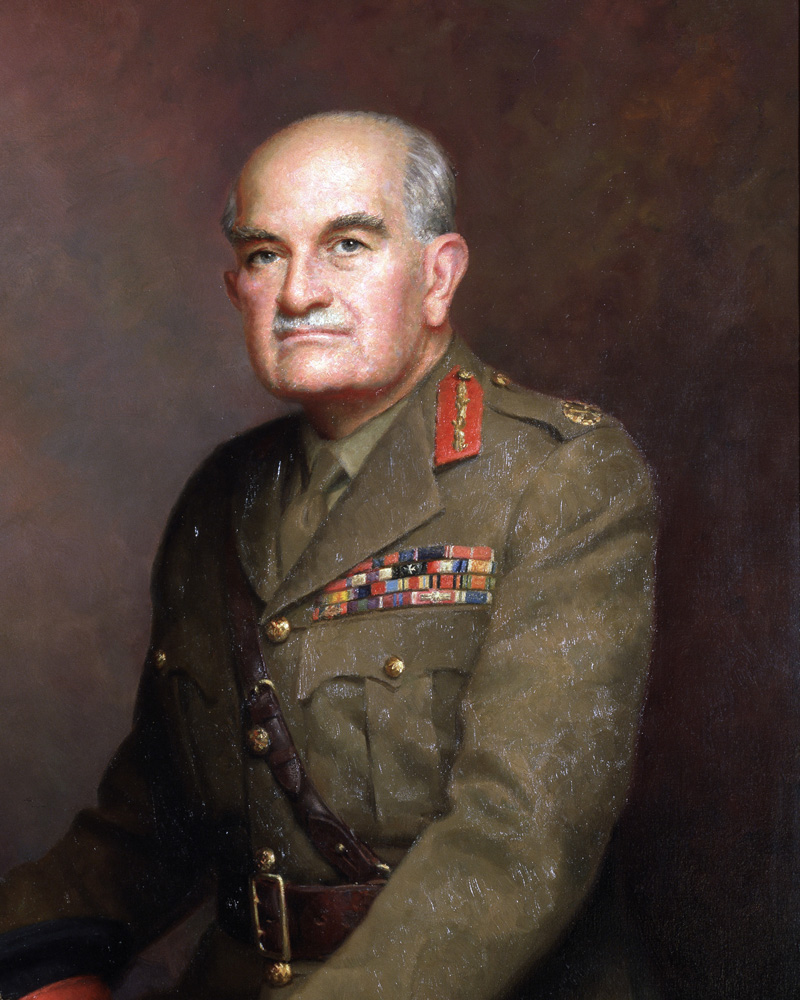

One of several exciting writing tasks this coming year – of which more anon – Mark Slim and I are currently producing, probably in three volumes, with Sharpe Books, a compendium of his grandfather’s pre-war writings. Between 1931 and 1940 Bill Slim wrote 44 articles – totalling 122,461 words, all under a pseudonym – for magazines and newspapers in the UK, India and Australia on a range of subjects, many dealing with the ‘lived experience’ of a soldier of empire. The collating and editing project is about half way through: I’m hopeful that by mid-year we’ll have the 3-volumes ready for publication.

One of several exciting writing tasks this coming year – of which more anon – Mark Slim and I are currently producing, probably in three volumes, with Sharpe Books, a compendium of his grandfather’s pre-war writings. Between 1931 and 1940 Bill Slim wrote 44 articles – totalling 122,461 words, all under a pseudonym – for magazines and newspapers in the UK, India and Australia on a range of subjects, many dealing with the ‘lived experience’ of a soldier of empire. The collating and editing project is about half way through: I’m hopeful that by mid-year we’ll have the 3-volumes ready for publication.

Editing this article today, first published in Blackwood’s Magazine in July 1937 and subsequently included in Slim’s own Unofficial History compendium of 1959, it struck me that it provides a useful contextual counter to the calumnies that are now de rigeur in the academy towards the way that the British empire was established and maintained. I was forced to read some of these recently in a dreadful book (reviewed here in my sub stack) purporting to demonstrate that the empire was stained blood-red by deliberate and deterministic violence, a violence that existed solely for reasons of political oppression.

Those with fairer minds and a better understanding of history than that particular author will recognise that this depiction of the British empire is a demonstrably false one. It is one designed for no other reason that to use the past to pursue a radically ‘progressive’ political agenda, one that actually involves destroying the past. Depressingly, a gullible and ill-educated West appears willing to lap it all up.

So read Slim’s own view of operations to support the Civil Power in the 1920s, and form your own view as to whether violence was a core feature of British oppression across its empire, or merely a universal feature of the maintenance of law and order in any civil society.

Before you read, a ‘trigger warning’: I trust that it doesn’t need me to tell you that in 1935 people used language differently to today. It was different country, then.

Enjoy!

In the days when Aurangzeb Alamgir still held a grip on his Empire, he built a fort at Gurampur; one of those lovely, rose-tinted Mogul forts, with great gates bristling with spikes to discourage butting elephants, and with overhanging machicolated galleries from which further discouragement could come sizzling down on beast and man below. For two hundred years after Alamgir had gone to reward in the highest heaven or torment in the lowest hell— to which destination you consign him depends on whether you are Musalman or a Hindu fort remained, a thing of beauty, but, oh, so insanitary!

Then came a new race of rulers, and, in their train, a bewhiskered Colonel of Sappers. He took one sniff at the fort, and the painted ceilings were whitewashed, the marble channelled fountains gave place to galvanised pipes, and the picturesque, ramshackle, incredibly smelly bazaar that filled the central courtyard was swept tidily away. In its stead rose the British Infantry barracks. They, too, were red; not the sun-soaked, mellow red of Mogul sandstone, but the garish red of good, honest Victorian brick. If their colour screamed a discord, so did their architecture — a Lancashire cotton – mill dumped in the midst of the Arabian Nights.

Yet, as the old Sapper could have pointed out, had anyone in his day been so blind to progress as to question his taste, these barracks had some advantages over their more artistic predecessors. For instance, you did not die quite so quickly in them. Then, some fifty years later, when the Military Works Department put in electric light and mosquito-proof fittings, what, asked the old Sapper Colonel, or at least his very image minus the whiskers, what more could the heart of the British soldier desire?

All the same, sitting in the bare whitewashed room that was my office, I did not like the place. Perhaps the thermometer, steady at 105 degrees, or the prickly heat round my waist, had something to do with it.

The fan that beat waves of hot air down on me clicked monotonously, and a sparrow twittered maddeningly from an iron strut in the roof. Sparrow

Did I say the barracks were mosquito proof? No, the Military Works said that, but neither I nor the sparrows believed them; I grabbed the pincushion from my barrack table and hurled it. With an indignant squawk the sparrow flew to another strut and twittered more maddeningly than ever. My babu replaced the pork pie hat that he had surreptitiously removed, rose from his table, and retrieved the pincushion. Without a word he put it back in its exact position on my table. No, I did not like Gurampur Fort, and I did not relish this standing by, day after day, with my company. Internal Security duty might be all right if anything ever happened, but this waiting . . .

I resumed my consideration of an objection-statement to a barrack damages claim returned by some minor deity in the financial pantheon:

“Ref. two panes glass, alleged broken by storm on 3 April. Meteorological reports indicate dead calm 3 April. Kindly explain.”

Rather a fast one, that, in the hot weather tournament between the unit and the Military Finance Department! Still, the great thing in these games is to keep the ball in play.

“When was our last earth-quake, babu?” I asked. Then the telephone rang. I reached for it, the objection-statement clinging to my sticky forearm in the infuriating way papers have in the hot weather.

An agitated voice in clipped English demanded—

“Why you not answering? Hello? Hello?”

“Gurampur Fort,” I replied in a pause in the babble.

“Is that O.C. Troops Speaking?”

“I am Personal Assistant to Deputy Commissioner Sahib. Assistance of British troops is urgently required!”

“What’s the trouble?”

“There is riot. Mob is committing violences at Meat Market.”

“Where’s the Deputy Commissioner?”

“At Market, confronting multitude in peril of life and…”

“Did he tell you to ask for troops?”

“Yes. He says come Kotwali at once.”

“Kotwali? The Government Offices, not the Market?”

“Yes, Kotwali. He wants you there. Kindly arrive with promptitude and despatch.”

“All right. Tell him we’re coming.”

Ten minutes later my company, less one platoon left behind under the only other officer, was ready. The men, as is the way of British soldiers, had cheered up at the prospect of action, and I shared their feelings until I suddenly remembered all the snags of this internal security business. I hurriedly checked over the contents of my haversack— sandwiches, chocolate, torch, map, note-book, field dressing, and, most important of all, in the pocket of my grey-back shirt Indian Army Form D.908.

I.A.F. 0.908 is a neat folding card, headed—

“Instructions to Officers Acting in Aid of the Civil Power for Dispersal of Unlawful Assemblies.”

Its three closely printed pages hold the concentrated essence of the four bulky legal volumes that control the soldier’s actions. While some of its instructions, such as “The Military are not to be used as Civil Police,” are puzzlingly vague, it is a very serviceable handrail to steady one among the pitfalls of the law. It has, also, a detachable fourth page which should be signed by the magistrate, if one is present, before he authorises the officer to take action.

Altogether, D.908, unlike many army forms, is a useful thing to have about one. I climbed into the leading lorry and we were off.

I’d not had much experience of the Salisbury Plain refinements of mechanisation, but I had done a good many miles over bad and winding roads in lorries packed with soldiers and their gear, and sometimes wonder, if the infantryman would be decanted on the battlefields of the future after a sixty-mile journey in quite the state of eager freshness some people expect. Perhaps he will, if somebody designs an army lorry in which all the exhaust fumes do not come up through the floor. As it was, even after the couple of miles to the city I was glad enough to get out.

The Kotwali headquarters of the civil and police administration, stood in a square at the very centre of the city. A gloomy, buff-coloured building with a verandah round the first storey supported on brick pillars, from which the plaster was beginning to peel. In the centre of the ground floor an arched tunnel led to a courtyard. On the opposite side of the square was the Imperial Bank, an imposing pseudo – classical portico with a huddle of ramshackle godowns behind, and a much bewhitewashed Telegraph Office. Hemming in these official buildings rose high, narrow, flat-roofed houses which looked as if they remained standing only because they were jammed so tightly against each other. Two or three wide streets of shops led out of the square, and, in turn, branched into narrow streets and dark alleys where wheeled trams could not go. A typical Indian city stewing in the unsavoury heat. There were a good many people moving about, but no signs of any disturbance, although I noticed that the shops were closed and shuttered. As we arrived Cornwall, the Deputy Commissioner, drove up in his open car. I knew him fairly well, a slight, dried-up man of about forty, with the stoop of a student and an unhealthy pallor bred of too many hot weathers.

With strangers he was shy, almost diffident and this, added to his appearance, often deceived people into thinking he was less a man of action than a Deputy Commissioner should be. Those who acted on this assumption received a rude shock, for Cornwall in his official capacity was a live wire. The Government of his Province used him as a sort of fire brigade. When the incapacity of a Deputy Commissioner caused a conflagration in any particular district, the incumbent, as is the kindly custom in the Civil Services of India, was promoted to the Secretariat, and poor old Cornwall was rushed off to replace him in the ruins. By the time he had rebuilt the edifice of Government there, the fire alarm was pretty sure to be ringing elsewhere, and so he went from district to district cleaning up the messes of men who were promoted over his head. He had a sense of humour, but by the time he reached Gurampur it was getting strained.

“Hullo,” he greeted me. “Thanks for being so prompt. I’ve left Marples tidying up at the Market. That spot of bother is all right for the moment, but things aren’t too promising. I’d like your chaps to stay here tonight, anyway. Come along and we’ll see what can be done to make you comfortable.”

I got the men out, piled arms in the courtyard, and let them sit in the shade. The lorries went back to the Fort for kit, mosquito nets, beds, rations, and everything else required for a possibly prolonged stay.

Marples, the Police Superintendent, arrived within half an hour with about twenty native police armed with buck-shot Martini-Henrys. His khaki shirt was black with sweat between the shoulders and round the belt, while his clean-shaven face looked thin and fine-drawn under its lank black hair. However, he grinned cheerfully enough at the sight of my fellows sprawling about.

The three of us then retired to Marples’ office, a big untidy room on the first floor. There, over three John Collinses, which a police orderly produced from a big ice-box, we began the conference between Civil and Military that all good soldiers know is the orthodox opening to co-operation.

Cornwall explained the situation.

“It’s the usual hot weather communal trouble, only it’s boiled up rather badly. The immediate cause is the new Meat Market. For some reason my predecessor allowed it to be built on the edge of the Hindu quarter; it’s a standing offence to them, and, of course, the Mohammedans have delighted to rub it in. A Hindu crowd tried to stop supplies going in early this morning, and if Marples hadn’t turned up just in time with his fellows there’d have been a useful riot. As it was, some of the Mohammedan butchers were badly beaten up, and one Hindu killed.

“Crowds have been trying to collect there ever since, and when I sent for you an hour ago it looked ugly. However, Marples again managed it after some very pretty lathi work, and it’s all quiet for the moment.”

“The trouble is,” added Marples, that there have been minor clashes in half a dozen places, and my police are scattered in penny packets all over the city. My only reserve is the twenty men I have below.”

We discussed how I could help, and eventually to my relief, for at one time they rather pressed me to scatter my men in small detachments, they agreed that for the present we should remain concentrated as a central reserve.

“What about a magistrate if I’m called out?” I asked, remembering that I.A.F. D.908.

Cornwall laughed.

“Want your card signed? I’ll get you a tame magistrate. Mind he doesn’t vanish at the critical moment, though. Magistrates are a bit shy sometimes. I don’t altogether blame ’em. It’s a rotten job for us, but they have to live among the people afterwards.”

We finished the John Collinses and the conference at the same time. Cornwall went off to his Court in the Civil Lines, and while Marples spent an hour at his routine office work, I saw my men settled in and their dinners under way.

I shared lunch with Marples, and he started on a tour of his Police Stations, leaving me with an Indian Police Inspector and the residue of the constables. I kept one of my platoons ready for immediate action and let the other two strip to their vests and get what rest they could under the nets.

It was fairly hot and I was standing in the archway, where there seemed a suspicion of movement in the air, when an imposing figure approached me —a burly, six-foot Indian. He wore a starched white puggri, a long black alpaca coat stretched tight across his broad chest, and voluminous Musalman trousers pinched in at the ankles. His aquiline face ended in a neatly pointed beard streaked with grey, and his dark eyes twinkled merrily as, slipping an ornate walking-stick under one arm, he held out a big hand.

“I am Jallaludin Khan, Special Magistrate,” he explained.

He was not at all the bespectacled, failed B.A. type I had been expecting. He looked as if he would have been more in his element leading an Afghan marauding expedition than dispensing justice in a stuffy Court. He spoke some English, and with my halting Urdu we managed very well. I gathered he was a local landowner, not a regular magistrate, but one roped in by Cornwall for emergencies. He told me he had offered to bring a party of his own tenants to help preserve order.

“You know, sahib—twenty, fifty of my people, sowars, with horses. But Deputy Commissioner Sahib say, No, no, you Jallaludin are enough. You more than fifty men!”—he laughed hugely and slapped a thigh—”Cornwall sahib, afraid I make zulm, oppression, on those Hindus, but—”he grew am magistrate, I serious, would be impartial. Yes, even with those sons of burnt pigs I would be impartial!”

We shared my tea. Jallaludin shovelled spoonful after spoonful of sugar into his cup, talking incessantly all the time, except when he sipped noisily at the boiling tea. While we were at it, the Police Inspector came in and said he had just had word from the Juma Masjid that crowds were collecting and trouble likely. He was going there with all the reserve police. I wondered if I ought to go too, but he did not seem to think so; he told me he would telephone if things got serious.

The flap, flap of his men’s shoes was very different from the tramp of soldiers as they hurried off, and as the sound died away the afternoon seemed very still. I sent a warning to the platoon on duty and resumed my tea. In a pause between Jallaludin’s sips I heard, like wind in trees, a murmur that rose from silence and sank again. Jallaludin heard it too. He jerked his head over his shoulder.

“The Juma Masjid,” he said, “crowds!”

The sound swelled up again. There was nothing menacing about it. It did not even seem human, more the sustained humming note of a distant machine. They are getting angry, announced Jallaludin. Suddenly the sound burst to a full-throated roar. I thought I could even distinguish shrill individual yells. Then it sub-sided again to a low growling. I did not like the sound at all. Then the telephone rang.

“Come quickly, sahib,” said the voice of the Police Inspector.

“Juma Masjid!”

He sounded to me like a man in need. I ran into the courtyard. The platoon was ready, and off we went at the double through almost deserted streets. As I ran, certain of the maxims on my I.A.F. D.908 crossed my mind: Keep your troops in a position to make use of their weapons . . . do not commit them to a hand-to-hand struggle . . . act in the closest co-operation with the civil authorities . . . get the magistrate to fill in the card.

Good Lord, but…where was my magistrate ?

But Jallaludin had not failed me. There he was, running extraordinarily lightly for a man of his bulk, just behind me. Puffing and sweating, we reached a point where the street debouched into a wide open space, but the entrance to this square was blocked by a solid mass of people, their backs towards us. All I could see was the great white dome of the mosque towering up against a brazen sky on the far side.

There was a tremendous noise, yells, cat-calls, shrieks, above a continuous din, and, every now and then, the crowd in front of us swayed backwards and forwards. Something was going on in the square, and equally evidently I ought to do something about it. But what? I had always pictured myself confronting a crowd, not standing behind it. It was very disconcerting. It was no use plunging into the mob; we should have been swallowed up. Besides, that would have committed us to a hand-to-hand struggle with a vengeance. I could not fire on the backs of the crowd; as far as I could see those near us were mere spectators and not engaged in any violence. The first essential was to see what was happening.

I looked at the houses—all barred and shuttered—it would take time to get in, and, judging by the row, time was going to be precious.

Then I saw a stationary motor-bus of the ordinary one-deck Indian type with a dozen people standing on its roof. I made for it, clambered up, helped by a huge heave from Jallaludin, who, with the platoon sergeant, followed me. The magistrate pushed the two nearest Indians violently off the roof, the rest took a startled look at us and followed them.

The bus made an excellent observation post. I looked out over the densely packed heads of the crowd, over a sea of waving arms and brandished sticks, to another crowd facing us, equally large, equally vocal, and just as formidable-looking. Between these two crowds was a narrow space along each edge of which I saw bobbing and swaying a thin fringe of scarlet puggris — the police. In the centre was a group of khaki figures among which I thought I recognised my friend the Inspector. A constant rain of missiles sailed through the air as one crowd bombarded the other or the police indiscriminately.

As I watched, a khaki figure staggered out of the line and fell. The mob on that side surged inwards. The Inspector with his little party flung himself into the breach. I could see their lathis going like flails as they beat the crowd back again. The stone-throwing increased; both crowds swayed ominously. Plainly the heroic efforts of the handful of police could not hold them apart much longer. Then not only would the mobs be at one another’s throats, but the police would be overwhelmed and probably beaten to death.

“Sahib, shoot! shoot!” urged Jallaludin in my ear.

“Shoot there!” He pointed to the crowd immediately below us. “Shoot them. The rest will run away!”

Even in the excitement I noticed, from the number of round hats and dhotis, that this was the Hindu faction. Jallaludin’s boasted impartiality was weakening under strain.

I reckoned that if I did not act within three minutes there would be wholesale murder in that square, so I got a section, five men, on to the roof, as fast as I could, and told them to lie down ready to fire. The bugler we had with us I ordered to blow the Commence Fire, the call we use on the ranges.

The bugle shrilled out above the clamour, and many heads turned to look at us, but beyond that it had no effect.

“Warn the crowd I’m going to fire,” I said to Jallaludin.

He plainly regarded this as an irritating delay, but, cupping his hands, he raised a mighty voice. I could not follow much of what he shouted, it seemed mostly abuse and threats at the Hindus below, but he did say the soldiers were going to fire.

A few near us began to slip away, but out in the square, where they had probably heard neither bugle nor voice, the noise increased, stones flew more viciously, and a couple more police went down. There was nothing for it but to fire.

I knelt down, tapped two of the men lying ready to shoot, and roared in their ears—

“Two hundred. At the front of the crowd facing us, one round, when I give the word.”

I gave a similar order to two other men to fire at the Hindu crowd.

And for God’s sake don’t hit the police!

The four men raised their rifles and aimed with all the stolidity of British soldiers in a crisis.

“Fire!”

The little volley crashed out, startlingly abrupt and shattering even-in that din. The crowd near us, terrified by the blast of rifles just over their heads, broke back and streamed away, but out in the square, whether they realised firing had begun or not, they held their ground and even closed in on one another.

“I ordered a further two rounds rapid from the same men. This time it had some effect. The crowds swirled and eddied on themselves for a moment. The police seized the opportunity, and hurled themselves on them. The mobs broke. In an instant they were making in wild panic for all the exits from the square. Luckily the roads leading away were wide and unobstructed, and in three minutes even the roof-tops had cleared.

There was an extraordinary hush. The square was empty except for scattered knots of police, and eight or nine crumpled figures lying still on the ground.

Leaving one section beside the bus, I extended the rest of the platoon and marched across the square. The whole ground was littered with stones, bricks, pieces of iron, sticks, shoes, hats, and bits of clothing.

The Police Inspector, dabbing with a rag at a nasty cut above his ear, met me. Hardly any of his men had escaped minor injury, and four of them were seriously hurt, one still unconscious.

I asked anxiously if there were any bullet wounds among them, and I sighed with relief when he answered—” No, sahib, only the ordinary stones, sticks, and one knife-stab.”

We turned to see what could be done for the casualties of the crowd. Of the nine left behind, five were past aid, and the other four seemed badly wounded. It is always rather a pitiful business seeing men you have shot, even enemies in war, and it was doubly so with these misguided devils.

We began to patch them up, the men using their own field dressings, until a policeman brought bandages from a chemist’s shop in the square. A little Hindu came out of this shop, announced that he was a doctor, and set to work. He seemed quite unmoved, intensely professional, and, as far as I could see, indifferent whether his patient was a Mohammedan or a Hindu.

When the motor ambulance for which we had telephoned arrived, I asked the little doctor if he would go with the wounded to the Civil Hospital. He hesitated for a moment, and then said, “If I am accompanied by British troops as escort.”

He evidently did not rely on his services to their wounded to protect him from his Mohammedan fellow townsmen. We commandeered the bus— its driver had vanished—and sent it off with the ambulance. I gave a section as escort to the party, and the little doctor went too. Before he left he very punctiliously gave me his card—a decent little man.

Then for the first time since I had left the Kotwali I had a moment to run over in my mind the action I had taken during the last half-hour.

The soldier always knows that everything he does on such an occasion will be scrutinised by two classes of critics— by the Government which employs him and by the enemies of that Government. As far as the Government is concerned, he is a little Admiral Jellicoe and this his tiny Battle of Jutland. He has to make a vital decision on incomplete information in a matter of seconds, and afterwards the experts can sit down at leisure, with all the facts before them, and argue about what he might, could, or should have done. Lucky the soldier if, as in Jellicoe’s case, the tactical experts decide, after twenty years’ profound consideration, that what he did in three minutes was right. As for the enemies of the Government, it does not much matter what he has done. They will twist, misinterpret, falsify, or invent any fact as evidence that he is an inhuman monster wallowing in innocent blood.

With some such thoughts in my mind I began to jot down in my note-book the sequence of my action while it was still fresh in my mind. I reached the point at which Jallaludin had asked me to fire—of course he was not entitled to do that, only to tell me to disperse the crowd, leaving the method to me—and I realised that, after two hours before dawn, and all, he had not signed my precious card.

I presented it to him.

I do not believe he could read it, though he pretended he could.

“You sign on the dotted line,” I explained.

He cocked his head on one side and looked thoughtfully at a dead Mohammedan the police were lifting into a lorry:

“I only asked you to disperse one crowd; you dispersed both.”

He seemed amused by something. Still —he smiled magnanimously—”I am magistrate and impartial. We will forget that.” His signature straggled all across the card.

By five o’clock in the afternoon one of my platoons was used up in piquets at the Mosque and the Market, and I was left with the other two at the Kotwali, which Cornwall and Marples had made their headquarters.

That night I had my first experience of patrolling a city in the dark. The heat, between the tall houses, pressed down like something tangible as we tramped through deserted streets and peered up dark gullies. It was all unreal and nightmarish, except for the smells, which were only too horribly real. Once I began to play a game with myself, counting them. I forget how many I had totalled when one more revolting than the rest made me retch, and I lost count. The narrower lanes of an Indian city on a hot night have to be smelt to be believed. I turned in on a camp bed two hours before dawn.

I awoke in broad daylight feeling beastly, with my bearer, who had followed me, offering the usual tepid tea. A shave and a hurried wash improved my outlook on life. Marples was still asleep; he had, in fact, just gone to bed, having been up most of the night making arrangements for the funerals of the men killed the day before. Cornwall I found at work.

“We are to have visitors,” —he said while I breakfasted; “some of the leading Hindus have asked to see me, and hearing, I suppose, that they had done so, the Mohammedans want to send a deputation too. I’ve told both parties to be here at nine, that’s in half an hour. You’d better attend the meeting, but don’t be drawn into any argument.”

The Mohammedan delegation arrived first. It consisted of two members. One, addressed as Maulvi Sahib, was a picturesque old gentleman in the black gown of a theologian, with a strikingly beautiful— there is no other word for it— face. He had the soft brown eyes of a contemplative, a beard like white spun silk. The other, an excessively fat man, was dressed in European clothes, but with a Musalman puggri. He wheezed a little as he moved, but his small eyes were keen and roved everywhere. He was introduced to me as Khan Bahadur Mohamed Zaman, and his profession given as contractor, a term which in India covers a multitude of activities and sometimes sins.

They were quickly followed by the first of the Hindus, Mr Bhagwan Dass, a wealthy merchant, almost but not quite as fat as Mohamed Zaman. He appeared to be a little put out at finding the rival faction present, but chatted with the Khan Sahib in a friendly enough way. There was a more distinct tension in the air when the rest of the Hindus arrived. They came together, naturally enough, for they were father and son. Imagine a Roman Senator with a brown face and sock-suspenders and you have the elder, Mohan Lal, lawyer-politician. The son, Debindra Lal, a leaner, taller edition of his father, was without his dignity, but had instead a sort of dynamic restlessness, the kind of repressed power that one feels in a wild animal pacing up and down behind bars.

Mohan Lal, as befitted a Roman Senator, opened the proceedings with a sonorous broadside. “As the mouthpiece of the Hindus of this city, nay, of all India, I protest against the callous massacre that occurred yesterday. I demand an impartial inquiry by non-officials. The Hindu crowd was a peaceful assembly, the funeral procession of a victim of Mohammedan outrage.”

This was too much for Mr Mohamed Zaman; quivering like a coffee blancmange he burst: “Peaceful assembly ! Mohammedan outrage! I, too, protest. I protest at the inactivity of the police who stood idly by while a Hindu mob attacked defenceless Mohammedans on the very steps of the Juma Masjid, and still more at the action of the military in shooting down innocent men defending themselves from this unprovoked attack.”

“Unprovoked!” exclaimed Mohan Lal, registering magnificent indignation.

Cornwall cut short his eloquence.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “in the first place, there was no need for the funeral procession to come anywhere near the Mosque; that was deliberate provocation”’—gratified murmurs from the Mohammedans. “In the second place, the attack was begun by Mohammedans.”

Both delegations tried to speak at once. Cornwall swept on, overriding them:

“Surely,” gentlemen, you could combine to use your influence to prevent such provocations and responses to provocations. I suggest you form a joint conciliation committee. As educated men of affairs, you should not find it difficult to agree on this.”

The appeal was not too enthusiastically received, and the spare Debindra Lal leant forward.

“You forget, Mr Deputy Commissioner,” he said suavely, “agreement has already been reached on one important point. Could we not start from that?”

“From where?” asked Cornwall cautiously,

From the necessity for an unofficial inquiry into the shooting. Both Mr Mohamed Zaman and my father insist on that. Could we not start from that very considerable basis of unity?

“I have satisfied myself,” answered Cornwall, keeping his temper admirably, that the firing was necessary, carefully controlled, and that it was the minimum required to disperse the unlawful assembly and thus prevent serious disturbance and great loss of life.”

Debindra Lal inclined his head courteously. “If that is your view, Mr Cornwall, why object to an inquiry?”

“Because, as you know only too well, such an inquiry is the last thing likely to help towards what should be the object of us all, the restoration of order.

“Nevertheless,” the elder Lal took up the running, unless such an inquiry is promised we cannot be responsible for the peace of the city.”

Cornwall’s voice remained quiet, but there was a hint of steel in it as he answered—

“You’re not, Mr Lal. I am! And I shall restore it—I hope with your co-operation. Our business is not to increase friction between communities, but to avoid it.”

“The true way to avoid friction,” proclaimed Mr Bhagwan Dass who, I thought, felt he was getting left out of things, “is to remove the cause. What is the cause? The Meat Market. Remove it!”

The obese Mohamed Zaman quivered again into protest, and communal feeling was running high when Debindra Lal made a diversion—

“There are guards of British soldiers at the Market and the Mosque. The sight of these men, responsible for yesterday’s shootings, is a provocation to both communities. Unless they are withdrawn there will be bloodshed.”

“If anybody is so foolish as to attack the Military, there will undoubtedly be bloodshed,” admitted Cornwall drily. “But if you believe it likely, Debindra Lal, there are only two courses of action honourably open to you.”

“And they are?”

“Either you do your best, publicly and honestly to dissuade these misguided people from attacking or—or you appear yourself in the very front rank of the attackers. Unless you do one or the other, we must doubt either your moral or your physical courage.”

Debindra laughed. He seemed genuinely amused, but his father watched him narrowly and, I thought, anxiously.

“Touché, Cornwall,” he conceded, “but you know very well I do not lack courage, and it’s no good your hoping I will oblige you by losing my temper and getting myself shot in a street brawl.” The discussion went on for some time. It was obvious that any real co-operation between the two communities was unlikely, and, whenever there was a sign of anyone co-operating with Cornwall, Debindra Lal threw a spanner into the works. Both sides seemed to be more occupied in scoring points in a three-cornered debate than in tackling any concrete question. The only exceptions were the old Maulvi, who took no part at all—I discovered afterwards that he could not speak English —and Debindra Lal, who was out for trouble.

The deputations departed in large American motor-cars, and I asked Cornwall,

“What’s Debindra Lal really like?”

“Brilliant at Oxford. Fine athlete. He’s quite right, we know he’s got courage, tons of it; drive, organising ability, and brains—first-class brains. It’s hard for a fellow like that to keep his head in India; he gets much more excitement, attention, and real power if he’s ag’in the Government than if he’s for it. Perhaps that’s our fault. Anyway, Debindra was blackballed for some potty station club, saw red— and went red. His old father’s terrified he’ll go and get himself shot or hanged one of these days. I doubt it myself ; he’s more likely to get a lot of his pals hanged and some of us shot.”

“He was pretty quick at switching communal into anti-Government feeling,” I ventured.

“Oh, anybody can do that. I’d guarantee to turn the tables by changing any anti-Government dispute into a communal one in twenty-four hours—only that’s not what I’m paid for.”

Marples came in, looking tired. He had got his reports for the night from his Inspectors. They showed that while there had been no major clashes, the disturbances were taking the form of isolated assaults on individuals, stabbings and bludgeonings in the back alleys —a very difficult business to suppress.

“Another Hindu has died in hospital,” he went on gloomily. “His pals will try to make a tamasha of the funeral this evening. I shall want all available police, and other parts of the city will be denuded. I’m nervous about attacks on Europeans. There’s a decided anti-Government—that means anti- European—tinge coming into things. We’d better get all British out of the city before this evening.”

“I think you’re right,” Cornwall agreed. There are only the fellows at the Bank, Borman, the American missionary and his family, and the Convent.”

It’s the Convent I’m worried about,” went on Marples. “There’s been a bit of stone-throwing there. I’ve had to put a guard on it. I don’t know exactly how many nuns and whatnots there are, but it’s a fair crowd. We’d better use the army lorries.”

Cornwall said, “Yes. Would you go along, and see to it, while I get on to Civil Lines and have the Circuit house ready for them?”

“All right,” I agreed dubiously.

Nuns, I felt, were rather outside my orbit, and I did not look forward to shepherding a mass of timid, cloistered women. As I rumbled off with a couple of sections in my lorries I practised reassuring phrases that would show the weeping nuns that I was gentle but firm. By the time we found the Convent, after losing our way twice, I was feeling quite the little Sir Galahad.

It was plumb in the middle of the Hindu quarter, packed in among rather better class Indian houses. A high brick wall, pierced by an iron-covered door, fronted the street. A couple of constables lounged against it; not, I thought, a very effective guard, but no doubt all Marples could spare.

One of them hammered on the door, and it was opened by a decrepit chowkidar. I—walked across a deserted playground towards along, three storeyed, red-brick building with pointed windows that gave it a semi-ecclesiastical air. I jangled a bell at the main door. After a little delay, a grille slid open and a face peered at me – a brown face framed in a nun’s white coif.

“I wish to speak to the Mother Superior,” I said.

After much drawing of bolts the door opened, and the little nun, her face very dusky against the starched linen, her hands hidden in voluminous sleeves, greeted me with a quick glance of big, rather frightened, eyes.

And then, as I live, she curtseyed to me. No one had ever curtseyed to me before, and it embarrassed me vastly.

I removed my helmet and attempted a bow. I felt, and I am sure looked, a fool, but I need not have bothered, for the little nun’s eyes were now modestly fixed on my boots.

“Please come this way,” she said in singsong English, and ushered me into a room. Please to sit down. I will bring Mother Angela.”

“Thank you,” I said, sitting on the edge of a very hard horse-hair chair. She curtseyed again. I rose hurriedly and repeated my bow.

She fluttered away and I looked curiously round the room. Three severe upright chairs, a plain table, and a prie-dieu were all the furniture on the polished linoleum. The walls boasted a big crucifix, a couple of German religious oleographs, and in one corner a small bookshelf. I tiptoed across to it—why I tiptoed I do not know, but I did. There was a New Testament, Douai Edition, next to a gilt-edged Grimm’s Fairy Tales, half a dozen odd volumes of some series of Lives of the Saints, and wedged between the last of these and a Latin devotional work, ‘Anima Devota,’ a paper-covered book of crossword puzzles. There was something else odd about the room besides this assortment of books—its smell. Not a particularly pleasant smell, but at any rate, a clean one, the first clean one I had met for some time, the smell of soap. Not the strongly scented variety, beloved of Indian servants, but good, honest, plain soap, the stuff you buy in long yellow bars.

I heard a brisk footstep in the passage, the door opened, and a nun entered. I knew at once that she was the Mother Superior because it was quite impossible that she could be anyone else.

Some years before, while my Sam Browne sat newly upon me, I turned from inspecting my platoon and found myself suddenly confronted with Lord Kitchener. He looked straight over the top of my head and said in a low voice, “You’ll all be wanted soon enough.” One of the men in the ranks behind me said, “My Gawd!” That was all. But from that moment I never doubted that Kitchener was a great man. Similarly, after seeing Mother Angela for a couple of minutes, I knew that she could not fail to be the Mother Superior of any community in which she found herself.

She was a tall, spare woman, and her black gown hung angularly, but the lean, brick-red face, with its deep-set eyes of brightest blue, and the hooked nose that jutted out over her wide mouth, could only belong to a woman of breeding and character.

She held out a large, well-shaped hand, and smiled, showing a gap in her strong white teeth. “You wished to see me?”

As I shook hands I quickly revised my ideas of the timid, hysterical religious. Rather nervously I explained my errand. Mother Angela listened patiently.

“But,” she said when I had finished, there’s no real danger. The people round here are better-class Hindus, they send their daughters to our school, they won’t do anything. A few hooligans from the bazaar may throw a stone or two, but we’ve had that before. Besides,” she went on, “if we run away, who’s to look after the Convent? It’ll be looted all right then!”

“Oh no,” I hastened to reassure her. “I’ll put a guard on it.”

“Then,” Mother Angela counter-attacked triumphantly, why not let us stop and put the guard on us ? If you give us half a dozen British soldiers, who will dare to molest us? Not that bazaar rabble!”

In vain I argued. She was very good – tempered, very reasonable, too reasonable almost, but she would not go. Finally, I temporised weakly and agreed to leave a section for the night pending a final decision.

Mother Angela, waving aside my suggestion that the men could camp in the playground, showed me a large classroom where they would be comfortable.

“But,” I said, “won’t it be very—er—awkward having men in your Convent like this?”

“Why?” asked the Mother Superior innocently.

I subsided in blushes. The old lady saw my confusion and relented. Putting her hand on my arm she said—

“My dear boy, even an old nun sees something of the army in this country, and I should be very happy to entrust my community not only to the valour, but to the courtesy of British soldiers.”

I surrendered completely.

In spite of the efforts of the police and our patrols there was a nasty crop of murders and assaults in the back streets that night. In the morning Cornwall promulgated a curfew order forbidding anyone to be abroad between sunset and sunrise, and we were fully occupied in preventing Mohammedan mobs from breaking in on the route of the Hindu funeral.

This was our third day, and after two nights with little rest we were all getting rather part worn. I relieved a platoon with the one from the Fort, but the police had no such exchanges to make. They had been at it longer than we had and much more constantly; indeed they were approaching exhaustion. Luckily we were able to take on much of the patrolling required to make sure the curfew was obeyed.

I used lorries for the main streets, every now and then going through the narrower lanes on foot with a police guide. Moving between the high, shuttered houses reminded me of those engravings of the Inferno; gloomy chasms, at the bottom of which a few forlorn mortals grope their way.

About an hour before dawn I stopped my two lorries at the mouth of such an alley and let the headlights shine down it. A solitary figure in the middle of the road turned and faced the sudden glare. We scrambled out and surrounded him. It was the little Hindu doctor who had attended the wounded outside the Mosque. He showed me his pass, signed by Marples, and said he was on the way to a case of childbirth.

“You’re very near the Mohammedan quarter; better be careful,” I warned him.

“I am almost at the house,” he said confidently.

“That one.” He pointed to a door a few yards farther on. I watched him walk up to it and knock. The lorry was backing into the main road again, and its lights swung off us, but I could still distinguish the little doctor by the white suit he wore. As he raised his hand to knock again a shadow detached itself from the shadows and flitted towards him. For an instant I saw a bare arm which rose and struck. There was a gasp, and the little doctor crumpled up.

The assassin slipped back into the shadows, but, as we dashed up the lane, I caught a glimpse of a running figure as it whipped down a side turning. A couple of men and my police guide stopped with the doctor, the rest of us plunged in pursuit. The man jinked again and again, but, clattering and panting, we hung on to his heels. At last, gaining on him, we emerged from a narrow entry into a wider street, just in time to see him scramble over a high wall. I jumped for the top of the wall. Built of dried mud, it crumbled, and I fell back. By the time my sergeant had given me a leg up again, the small courtyard into which I looked was empty, but a soldier, astride the wall already, called out excitedly:

“He’s gone in there, sir! I saw the door open and he went in!”

I dropped into the yard and shone my torch on the door, a stout one enough. A good shove showed that it was firmly locked. I kicked on it till my toes ached, but with no result. While I was thus rather futilely occupied, the sergeant, with more presence of mind, had posted men to watch the windows and the road outside. I left off hammering and made a quick reconnaissance. The house stood on a corner, so that it had the street on two sides, the courtyard on a third, and only the fourth abutted on another house, a much smaller one, its roof so much lower that it would have been impossible to drop from one to the other. If the murderer had gone in he must still be there. The obvious thing was to search the house. I returned to the door.

I remembered reading of Bulldog Drummond or some other hero, who, confronted with a locked door, whipped out his pistol and blew away the lock. I drew my revolver, presented it at the huge keyhole, told the men to stand back, and loosed off. There was a great deal of noise, and a bit of metal whirred back over my shoulder, but as for any practical result on the door—nothing.

I had effected something, however, for a shutter on the first floor creaked open and an old man’s head cautiously emerged—

“Kaun hai? “Who’s there?” he quavered.

“Open the door!” I yelled. “I am a British officer. Open!”

“Chabi nahin hai,” there’s no key!” he piped.

“It’s no use talking to him, sir,” interposed the sergeant. “This’ll do the trick.”

Four men appeared with a heavy wooden bench they had discovered in the yard, and began a thunderous assault on the door. At the third blow we heard someone removing bolts inside. The door opened to show the old man standing in the bright light of an electric lamp. He was protesting volubly, and could not or would not understand my inquiries about the fugitive. I had never searched a house, and this seemed a big one. By the time I had posted men to watch the outside and left two at the door, I had only the sergeant, myself, and four men left.

We started on the ground floor, offices, a kitchen, and a storeroom with no signs of a cellar. “Old Methuselah,” as the sergeant dubbed him, continued to wail his protests, and was joined by two more men, an old one rather like himself, probably a brother, and a younger one, possibly a son, fat and middle-aged. They both jabbered in Hindustani, but so fast that I could not follow.

In due course, having drawn a blank, we moved up to the first floor. Here were the main living-rooms, filled with an incongruous mixture of Victorian oddments of the antimacassar period and purely Indian furniture. The effect was garish and untidy; the air of an abominable stuffiness. Here we met a fourth Indian, a young one, and I was puzzled. The man we were after could not be either of the ancients; the middle-aged one was far too fat; but this young man? Finally, I decided he was too tall, and gave him the benefit of the doubt, for the present.

After a search without result I made signs that I would move to the next floor. A storm of protest arose, but, ignoring it, I advanced to the foot of the stairs, and there I came to a full stop. A carpet hung across the steps. In front of this purdah stood an old woman: she might have been of any age from seventy to a hundred, who, as soon as I approached, began to scream imprecations and abuse in a high, cracked voice. She held a strip of muslin over her mouth, but, as she warmed to her tirade, it slipped, and she never bothered to replace it. Her face was the colour and texture of a walnut shell; nose and chin almost met over toothless gums, but her black eyes were bright and baleful enough. I tried to explain to her men-folk that she must let us pass. They only joined their outcry to hers. At last in desperation I gave the order –

“Shift her out of the way as gently as you can.”

The sergeant advanced on her making pacific noises.

“Now, now, mother,” he cooed ingratiatingly.

The fat, middle-aged Indian suddenly broke into good English.

“This is a Musalman house,” he said. That is the zenana; you cannot go in.”

“But we must. How else can we search the house?”

“ You cannot go,” he reiterated.

I began to feel I was not on quite so good a wicket. I pictured the outcry that could be worked up if I forced an entrance into the zenana, especially if I could produce no justification. I wondered what my legal position was. I hesitated. The pandemonium died down. I could hear whisperings and shufflings beyond the curtain. My own men, the Indians, all looked towards me. An uncomfortable moment, but I felt my name would be mud if I gave way now.

I turned to the fat man.

“Tell all the women to come down and go into that room we have left. You can put a purdah over the door. My men will not enter. We will then search the upper rooms.”

More protests, but by now I was growing angry. I issued an ultimatum. Either the women came down or I searched upstairs with them there. A hurried consultation between the men-folk and the old woman resulted in their giving way, and she vanished through the curtain.

Soon a procession of about a dozen women of all sizes, muffed in flowing bourkas, shuffed down the stairs. The old hag placed herself on guard, and at last some of her abuse was diverted from us to the presumably younger and more flighty women who kept peeping out at the white soldiers. Leaving a couple of men to see that none of the women came out, the sergeant, the other two, and I began our search upstairs. The furniture here was almost all Indian; mostly low beds, covered in plaited webbing, some of them with elaborately painted legs. There were several heavy chests, rickety wardrobes, some good rugs, and untidy heaps of clothing. In one room stood a European dressing – table covered with sticky pots of cosmetics. The air was stale with heavy perfume, and what was once euphuistically described to Queen Victoria as ‘esprit de corps.’

We delved into every hiding place that could have held a man but without result. Yet my soldier was positive that he, had seen the fugitive enter, and something in the manner of its inmates convinced me that he was still in the house. It followed then that he was either one of the four men we had seen—and I did not believe he was—or he was among the women. The more I thought of it, the surer I was that that was the solution. For all I knew there might be half a dozen men among them. How I longed for one of those imposing policewomen who watch you take your ticket in the Piccadilly Circus tube or if only Mother Angela had been here she would have winkled the fellow out in two minutes; but it was no use wishing, something had to be done.

To demand to see the ladies’ faces was out of the question. Completely at a loss, I turned to my sergeant. As a married man he might have some ideas. Splendid fellow, he had !

“We might be able to tell, sir,” he suggested, “if we looked at their hands and feet.”

This seemed an excellent scheme, but I was sure that if I simply demanded to inspect their hands and feet I should be met by another outburst of refusal. Guile was indicated.

“The man we are after may be among the women,” I said.

“Impossible!” snorted the middle-aged Indian.

“Nevertheless, I must be sure.”

He began to protest, but I cut him short. The man has a finger missing from one hand. If all the ladies as they pass out will show their hands that will be enough to satisfy me whether he is there.”

The Indians held a hurried consultation in whispers. At last the spokesman said—

“All right. We will allow that, but we protest at the outrage.”

There was a great deal of chatter and shuffling among the women, but in a few minutes they began to come out, one by one, passing between the sergeant—and me.

The old woman came first, holding out gnarled claws and saying something particularly biting which luckily I could not understand. We inspected another hall – dozen pairs of hands, mostly small and well-shaped, some with henna-stained nails, some not over-clean, but all unexpectedly fair and undoubtedly feminine.

Then seventh or eighth came a muffed figure with hands that, though not larger, were a shade darker than any that had gone before. True, they drooped languidly from the wrists, yet those very wrists were by no means innocent of black hair, and there was a hint of sinewy forearm.

I looked quickly at the Indian men-folk. They were silent, and I saw anxiety in their strained intentness. I caught the sergeant’s eye. He nodded almost imperceptibly. Still I hesitated. A mistake would be most unfortunate. How were we to be sure?

The sergeant rose again to the occasion. With seeming carelessness he let the butt of his rifle fall sharply on a slippered foot. Instead of a feminine squeal, there burst from the bourka an undeniably masculine howl!

It was broad daylight when we got back to the Kotwali with our bag—for we had collected all the male members of the household as accessories after the fact. When he heard of our exploits, Marples mustered a grin.

“The military will not be used as Civil Police,” he quoted, “and don’t ask me how much of your action was legal! But we’ll put that chap where he’ll get what’s coming to him.”

While he was speaking, the telephone rang to tell us that two more companies of my battalion had arrived by train during the afternoon to relieve mine in the city. I felt as if I were deserting Marples and Cornwall, both of whom had already been working longer than I had and under greater strain, but I must confess that after four days and nights of ‘Aid to the Civil,’ I was glad to pack up.

That night, back in my old brick barracks in the Fort, I crept under my mosquito curtain and lay with a towel round my middle my middle under a slowly ticking fan. Drowsily I passed in review the varied figures of the past few days: Jallaludin the magistrate, Debindra Lall, Mother Angela, the little Hindu doctor, the old hag in the zenana, and the rest. My mind ambled on, but, after all, I fell asleep raising a metaphorical topi to the man who had provided me with a place where I could lie in what I realised now was comfort, and breathe air that did not poison me—to that old bewhiskered Colonel of Sappers.