This poor thing looks like it was rode hard and put away wet to me. Grumpy

This poor thing looks like it was rode hard and put away wet to me. Grumpy

Laying prone at the Crusader Range at the SAAM Shooting School on the FTW Ranch in Barksdale, Texas, I was presented with the challenge of making two consecutive shots: the first at 325 yards, and the second at 500 yards, with only 10 seconds between the two. Upon report of the first, the countdown began.

While the first was steep downhill to my left, the second was much flatter, but almost 90 degrees to my right. It would require setting up for the first shot, and making not only a scope adjustment to compensate for the difference in trajectory, but completely realign my shooting position to punch the steel plate.

All this to simulate a game animal moving at varying distances, and to teach the skills needed to make the shot—or sometimes to teach you what shots are beyond the shooter’s capability.

Having been to this facility several times, and being familiar with the ever-changing winds which flow through those canyons, I’ve found that a flat-shooting cartridge with a decent velocity and a high ballistic coefficient (BC) can make your life much easier. This particular day I was shooting the classic Remington Model 700 rifle, chambered for the brand-new Hornady 7mm PRC; this new design certainly got the job done.

Hornady has made waves with their 6.5 PRC (Precision Rifle Cartridge), which was based on the now-obscure .300 Ruger Compact Magnum, as well as the .300 PRC, based on the .375 Ruger; both parent cases were designed by Hornady in conjunction with Ruger.

While the .300 PRC has a maximum cartridge overall length of 3.700 inches and requires a magnum action for best performance, the 6.5 PRC has a 2.955-inch overall length and can fit in a short-action receiver, the new 7mm PRC sits right in the middle—clearly designed for the long-action receiver, and putting the cartridge smack in the middle of the previous two releases.

The 7mm PRC maintains the same 0.532-inch rim and base diameter as its older siblings; you cartridge hounds may recognize that number as the H&H Belted Magnum rim and belt diameter, but the PRC family and many other Hornady designs use that for the body diameter. Being a rimless design, the 7mm PRC will headspace off the shoulder, and it keeps the same 30-degree shoulder angle as its relatives. The 7mm PRC’s case length comes in at 2.280 inches, with a maximum cartridge overall length of 3.340 inches, the same as the .30-06 Springfield.

There are currently three loads available, but at the time of this writing, the only one I could get my mitts on for testing was the 180-grain ELD Match, cruising along at a muzzle velocity of 2975 fps. The also a 175-grain ELD-X Precision Hunter softpoint running at 3000 fps, and a 160-grain CX Outfitter at a muzzle velocity of 3000 fps.

Measuring the factory cartridges, I observed an average overall length of 3.2910 inches, which means there might be a bit of room to seat that long, sleek bullet out even further, but based upon the way it shot, I see no reason to do so. That long sleek bullet has a G1 BC value of 0.796, and the folks at FTW clocked it at 2955 fps—certainly in step with advertised velocities. And for starters, the 100-yard accuracy was certainly sub-MOA, with some groups running as tight as ½-MOA during our range sessions to zero the rifle.

As per the usual FTW routine, targets are engaged at all sorts of distances, from sane hunting scenarios to next-zip-code shots, and the 7mm PRC handled them all well. Our rifles were topped with Swarovski Z8i 3.5-28x50mm scopes, with the BRX-1 reticle; while larger in both magnification and objective lens size than I would normally choose on a hunting rifle, these were good choices for reaching out past 1,200 yards. While the scope’s elevation turret was marked in mils (with a series of raised yardage markers, which I felt were absolutely perfect for hunting), I will describe the trajectory in inches of drop, just to illustrate the point.

With a 200-yard zero, the 7mm PRC will rise 1.4 inches at the 100-yard mark, dropping 6 inches at 300 yards, 17.1 inches at 400 yards and 33.7 at 500 yards. Being completely honest, with a cartridge of this velocity and trajectory I’d prefer to use a 250-yard zero. Doing that will see a rise of 2.50 inches at 150 yards, but a 2-inch drop at 300 yards, and a 6-inch drop at 350, giving me a dead-hold on a deer’s heart to roughly 325 yards. If simplicity appeals to you, a trajectory like this will cover the vast majority of you hunting shots. With this zero, 400-yard shots will drop 13 inches, and 500-yard shots drop 27 inches.

While I personally have no business shooting at unwounded big game past 500 yards (a self-imposed limit, based on my real-world experiences), we did have fun stretching the 7mm PRC’s legs on steel targets, taking it all the way out to 1,500 yards confidently, and making several hits just past the one-mile mark. Bottom line? The 7mm PRC has the goods to make long range shots confidently, and as this is American Hunter, our concerns are targets much closer than that of the true long-range competition shooter.

Recoil? I found the 7mm PRC to be totally manageable, though some folks who don’t regularly shoot magnum cartridges proclaimed it to be a bit stiff. I have had some 7mm Remington Magnum rifles beat me up much, much worse than did the Model 700 in 7mm PRC, and putting 60 to 75 shots per day from the prone position didn’t crush my shoulder. In a hunting situation, where you’d spend a bit of time zeroing the rifle, and then firing a few shots at game, I can honestly say that you wouldn’t feel the recoil at all.

Does the hunting and shooting world need a 7mm PRC? Well, I think the answer to that question is yes. Yes, the .300 PRC offers heavier bullet weights, yet it requires a longer action and comes at the price of much stiffer recoil. The 6.5 PRC is a great cartridge, but with bullet weights south of 145 grains, I feel it is limited in the game species for which it is applicable.

A 175-grain lead-core hunting bullet, or perhaps a 160-grain monometal, will allow the 7mm PRC to join the “all-around” club, being able to take all North American game shy of the huge coastal grizzlies, and the majority of African species with the exception of the true heavyweights. All this in a beltless case which won’t have any of the stretching issues that the belted cases have, which offers great concentricity and excellent accuracy; I can’t see any reason not to choose the 7mm PRC.

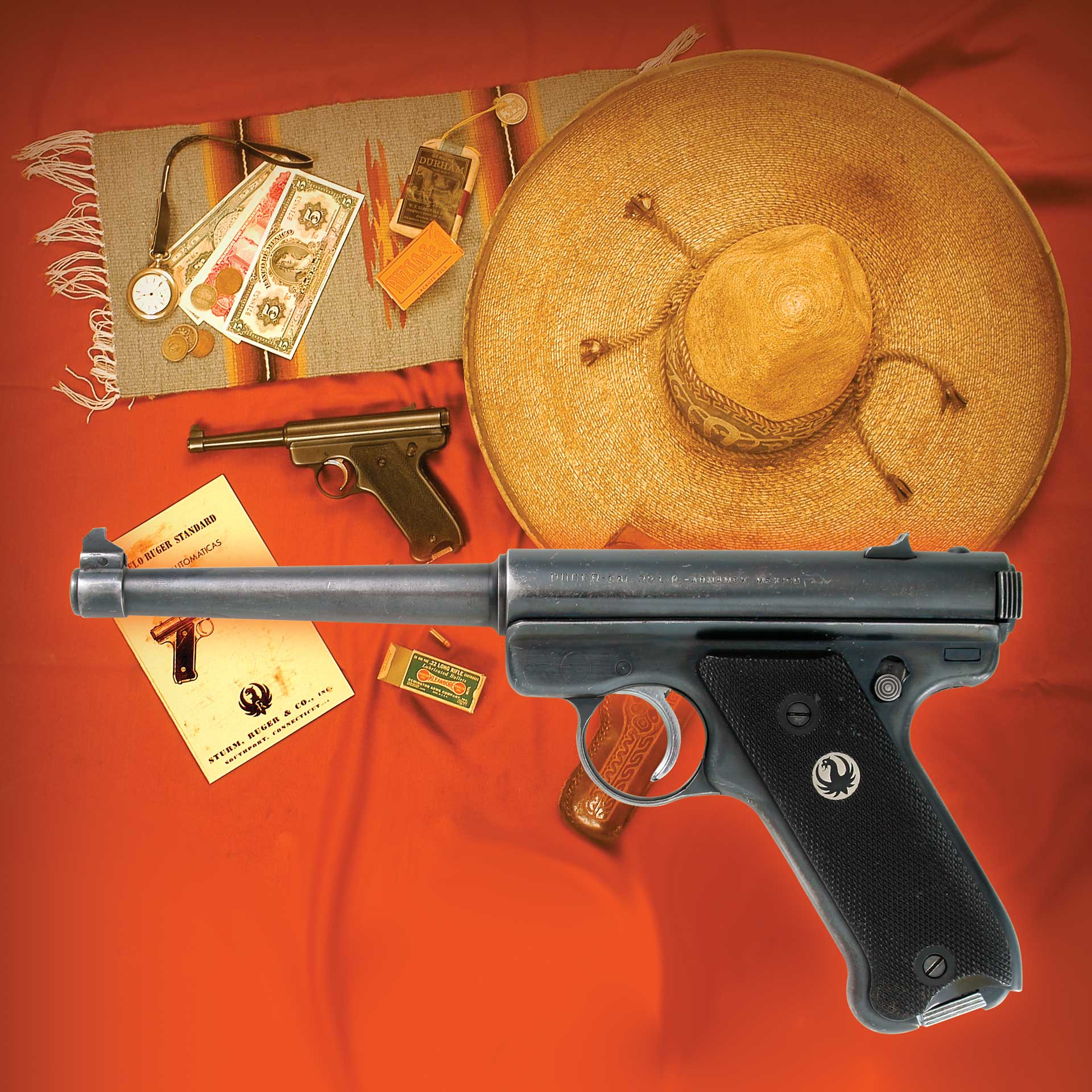

This feature article, “Ruger: Hencho en Mexico,” appeared originally in the July 2005 issue of American Rifleman. To subscribe to the magazine, visit the NRA membership page and select American Rifleman as your member magazine.

Colonel Rex Applegate was born in Yoncalla, Oregon, in 1914. He graduated from the University of Oregon in 1939 with a degree in business administration. That same year he joined the U.S. Army as a second lieutenant in the Military Police Corps and eventually rose to the rank of colonel. Applegate had an interesting and colorful career in the service. He was the head close-combat trainer for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) during World War II and became the acknowledged expert in close combat, working on the design of combat knives with British Commandos. After returning to the States, Applegate was assigned to special duty at “Shangri La,” now known as Camp David, Md., to guard President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

After a distinguished military career, Col. Applegate retired from the regular Army with a combat disability in 1946. A residence with a dry, warm climate was recommended. While in the military Applegate became acquainted with an officer who had retired to Mexico. On his recommendation Applegate visited Mexico and decided the climate was right and commercial opportunities there looked promising. During this time the officer who recommended Mexico to Applegate had obtained a distributorship and opened an assembly plant for Nash Motors, in Mexico City, called “Nash Motors of Mexico.” Applegate was employed in 1947 as service manager.

The colonel’s interests did not lie in automobile production but in what he knew best: firearms, or at least a firearm-related business. During the war, Applegate became very well acquainted with the management at Smith & Wesson. It was through that acquaintance that he was able to break into the firearm business. Dave Murray, S&W sales manager, contacted Applegate in Mexico. The timing was perfect. Applegate was able to obtain 1,000 .22 S& W K22 revolvers. The new K22 Masterpiece, a replacement for that model, had been introduced in the States and Smith did not want these 1,000 revolvers on the U.S. market. Applegate marketed the guns in Mexico. The venture was highly profitable as the Mexican population was eager for any type of firearm.

Applegate resigned his position at Nash Motors to form his own company, Cia Compania Importada Mexicana (The Mexican Importing Company). Financing was furnished by Frank Sanborn, owner of the famous Sanborn Drug and Restaurant of Mexico City. Applegate operated in Mexico from 1948 to 1955 as factory representative for S&W, Remington, and Peters Ammunition, as well as a U.S. chemical company that produced a line of tear gas. He also served as representative for a number of U.S. fishing tackle firms, as well as other allied firms in the sporting goods industry.

Laws governing import duties in Mexico were changed in 1955. Prior to that time import duties were quite low. Afterward, not only were import duties raised, but products sold in Mexico were required to be 40 percent manufactured in Mexico. A manufacturing and assembly facility was needed, and Applegate established Armamex, S.A. The Armamex manufacturing and assembly plant was located in the city of Pachua, State of Hidalgo, approximately 90 miles north of Mexico City. He was president and in charge of sales and retained all U. S. contracts. Financing was furnished by W.O. Jenkins, a wealthy American residing in Puebla, Mexico. Eugene Everhert, an American gunsmith and long-time Pachua resident, was hired as plant manager.

Everhert was an engineer at a local silver mine until that time. P.O. Ackley was brought in for assistance in setting up the new plant and to perfect Armamex’s barrel making operation, and Ackley’s employment was on a temporary basis. Another American gunsmith, who also lived in Mexico, was in charge of assembly and quality control. Management was basically American, while the labor force was Mexican. Firearms assembled in the plant were stamped “armamex, mexico” and/or “hecho en mexico” (made in Mexico).

Sales were through Cia Compania Mexicana. Applegate’s companies served a network of approximately 200 Mexican arms dealers. Firearms consisted of a single-shot .22 rifle manufactured entirely in the Armamex factory and a single-barrel, Iver-Johnson shotgun. Stocks and barrels for the shotguns were produced by Armamex to comply with the local 40 percent manufacturing law. These economical hunting arms seemed to fill the needs of the local population, and shotguns and .22 rifles were not considered a security threat by Mexican military officials. The Mexican military was the source for licenses and permits, and revolutions aren’t usually fought with either type of arm.

With the successful marketing of these economical long guns Applegate decided to offer a line of better-quality sporting arms. He made a trip north to the United States to meet with manufacturers in order to fill this new firearm line. This was either late 1955 or early in 1956. He struck a deal with Bill Donavan of High Standard for several hundred .22 Sport King pistols. In a meeting with Robert L. Hillberg, owner of Whitney Firearms, Inc., of New Haven, Conn.,

Applegate made a deal for 200 .22 Whitney Wolverine pistols. In a letter from Mr. Hillberg, he (Hillberg) recalled how the transaction was accomplished, “Bob Dearden was our key man and the entire transaction was with him. Bob devised a method of identifying the individual component parts and packaged them in a manner Applegate could receive and assemble the original guns without mixing any of the parts. Rex shipped the parts to a company in Texas. How he got them into Mexico, I have no idea.”

Applegate’s close friend W.H.B. Smith, firearm expert and author, arranged for a meeting with William B. Ruger, Sr., of Sturm, Ruger & Co. Ruger and the colonel struck up an instant friendship. The two men shook hands and made an informal agreement. Applegate purchased 200 Standard Model Ruger .22 pistols, and they were shipped to the American Firearms Company at Brownsville, Texas, (a company Applegate had organized with U. S. licenses for purchasing and exporting firearms). A representative of Armamex was sent to Texas to receive the shipment and they were disassembled there. Parts were marked and bagged with caution not to mix the parts from one gun with another. The parts were imported to Mexico, but Applegate’s Mexican import permits covered parts only, not complete firearms. The High Standard and Whitney pistols were shipped in a similar manner. These transactions were an experiment and not repeated.

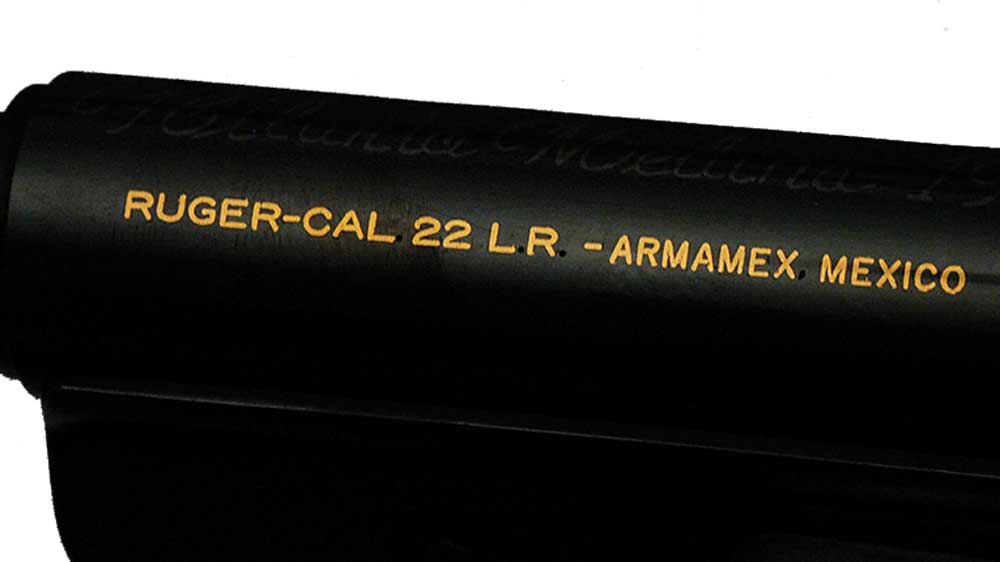

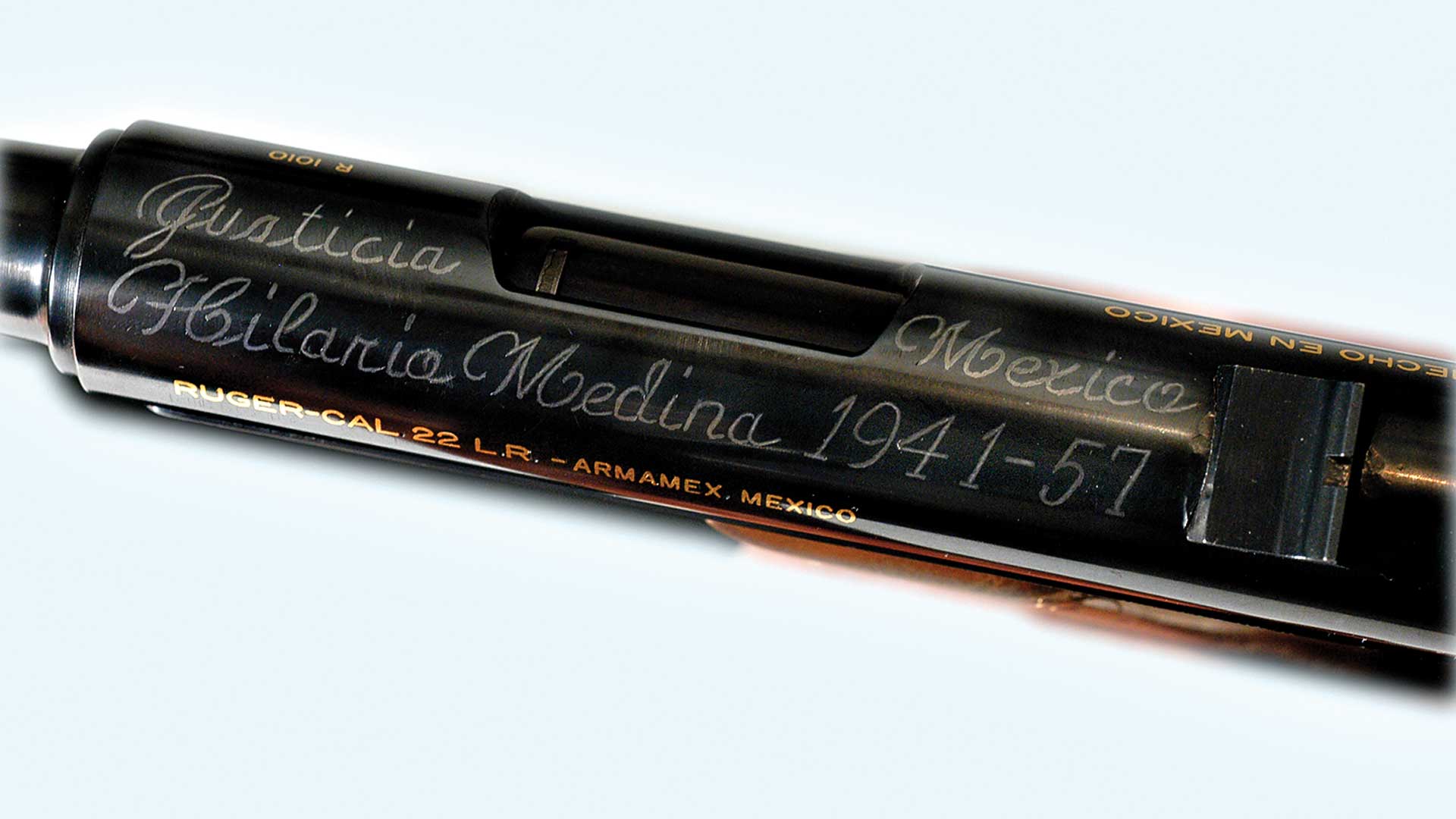

On arrival at Armamex the pistol parts were roll-marked, blued, and assembled. The Ruger pistols were serially numbered with the letter prefix “r.” Rolled on receiver’s right was “hecho en mexico,” and the left side was marked “ruger cal. 22 l.r. armamex mexico.” The Whitney and High Standard pistols were marked “armamex mexico.”

The finished pistols were then shipped from Armamex to Cia Compania Mexicana and on through the Mexican network. All the Ruger pistols were shipped except one that Applegate put back and later gave to Bill Ruger for his personal collection. Although successful, Applegate—realizing the position he and his companies could be placed in with the Mexican authorities—elected to discontinue the importing of either complete U.S. handguns or parts. His Mexican firearm operation was built around rimfire single-shot rifles and shotguns, and Applegate decided to return to that. His degree in business administration had served him well.

Armamex operations continued until 1962 when Applegate was recalled by the military for special duties in relation to riots in the United States, and he left Mexico in 1963.

Armamex continued to operate for several more years, but it eventually folded due to poor management—along with increasing government interference. The Mexican government ordered seizure of all firearms in the early 1970s. Sporting goods stores were forcibly closed, and inventories were confiscated.

Rules can be bent in Mexico if the right generals are approached, and money put in the proper pockets. Some of the Armamex pistols have found their way out of Mexico, but fewer than a dozen Armamex Ruger pistols are known in private collections—and even fewer High Standard and Whitneys have been located. All of Applegate’s records and photographs on the Armamex operation along with guns from his personal collection were confiscated.

Sadly, Rex Applegate died on July 14,1998, at the age of 84. One of this great man’s many legacies remains a handful of Ruger pistols that were “hecho en mexico.”

The Smith & Wesson 340PD (top) is one of the most potent and versatile pocket

carry guns in the business. For low-profile carry, the Kahr P380 weighs 9.97 oz.

unloaded, and has an overall length of 4.9″. The DeSantis Nemesis pocket holster

has enough foam to cover the outline of the gun and an extremely tacky outside cover.

Image: Robert Marvulli

I am an advocate of pocket carry, specifically strong-side, front-pocket carry. I teach it. I practice it. I carried a gun in my pocket both on and off duty.

Many people carry their guns in their pocket, but don’t train with them. Every handgun/ammo/holster combination needs to be considered part of a system that is integrated into a defense plan. With pocket guns, it is important to incorporate fighting skills and force options into the plan.

Like every other carry method, obtaining the master grip is the key to the draw. There are times when shooters can move subtly and draw without alerting anyone they are armed.

In fact, a person can assume a shoulder slouched, hands in pocket demeanor and no one would suspect the state of readiness. If we wish to assume a “millennial posture,” simply add an electronic screen attached to the nose. Since pocket carry doesn’t require unsnapping a retention device, the user can smoothly clear the pocket, orienting “this side toward the enemy” the moment the muzzle is free.

Drawing quickly requires smoothly sliding the fingertips into the pocket opening. For me, the type of pocket is the first consideration when purchasing a pair of pants. The pockets need to be deep and made of cotton or a reinforced material that does not stretch. If the structure of the pocket is solid, the pocket holster will keep it in a consistent position.

A couple of pairs of pants (Propper and 5.11) I have easily accommodate my S&W M&P Shield, a tool I like to have in a target-rich environment. Both companies use a pocket angle that makes it easier to get the fingers into the openings. Even their “less tactical looking” models work for J-Frames.

Chino-style and dress pants require lighter handguns. I like the S&W 340PD for this purpose. If the choice is an auto, I recommend the Kahr PM9. Both guns are under 15 oz.

Ideally, one should carry at least two reloads — two magazines or two speedloaders. If the gun is a revolver, at least one speedloader is carried on the gun side. I like to have both a speedloader and a speed strip. If the gun is an auto, at least one magazine is carried in the front or back non-firing side pocket.

Draw with the shooting-side leg behind the hip. For right-handed shooters, the left foot should be forward and the right leg back. If the shooting-side leg is bent, it can bind the draw.

Drawing from the pocket when seated is challenging, but it can be done. First, try to avoid any seated position where the knee is higher than the hip. That is, if the thigh is higher than parallel to the floor, the draw is interrupted. Rotate the hips to allow the gun side leg to straighten. This may require rising to a standing or partially standing position. In a restaurant booth or a bench, this can be accomplished by sliding partially off the bench and sliding the gun-side leg back.

Drawing from the “crucible,” when the threat is within arm’s length, requires some sort of clearing motion that prevents the draw stroke from being interrupted. We call this a “clearing strike.”

If the threat is close enough to touch, especially when there is a possibility of multiple threats, a distraction strike may be required. A distraction strike is a deliberate impact on a targeted area used to freeze the opponent and keep them off balance. I don’t just want to clear the draw. I want to shock the opponent and expose vulnerable areas.

I could get into all kinds of technical martial arts stuff, but I could also give you simple directions, making you more effective in your fighting ability.

Most empty hand strikes include throwing a specific body part at a target and retracting it. In this case, you’ll strike at the base of the opponent’s neck, but your striking hand stays on the base of the neck. That is, you are striking, and “sticking.” The purpose is to strike, then continue to drive the person rearward, upsetting their balance. The first strike is done with the shooting hand.

This concept is something on which a person can spend a lifetime, but if you understand it, it may help you today. Any blow to the base of the neck works, with varying degrees of effectiveness. Your job is to stun the opponent so you can move onto something more effective.

What part of you hits the base of his neck? It can be any part of the outside blade of the hand, all the way to the middle of the forearm. You are welcome to make a fist or use a “karate chop.” Don’t use the fingers, unless you have spent many hours developing them for this purpose.

Deliver your strike with the gun hand, then drive forward, sticking on the opponent. You are successful when your opponent fails to move backward as quickly as you are driving him. If your activity drives your opponent into another object, or causes him to stumble, this is good. Keep driving.

While striking with your shooting hand, your support hand needs to be seeking their hand. Pin their hand against their body. The purpose here is to jam the draw.

Once the opponent is moving backward, switch hands. That is, strike again to the base of the neck with the other hand, and continue driving forward. Now your shooting hand is free to draw. You now have your gun, and he does not have his balance.

At this point, perform a target assessment and shoot if necessary.

Please bear in mind this is a single technique from a system of techniques. If you want to train further, find a competent school that teaches a well-vetted system.

The second part of the distraction strike is to switch hands by delivering the same

type of strike at the neck with the other hand, keeping your opponent off balance.

The opponent’s hands will be raised in an effort to maintain balance. Now the shooting

hand is free to draw. Depending on the amount of control the shooter has over the

opponent, he can assess, deliver a decisive strike or draw and shoot. Image: Robert Marvulli

Over the past seven years, small guns in calibers of confidence have emerged on the market. This trend is coupled with the vast improvements in terminal performance of cartridges. No one is saying, “Don’t get a 9mm. They aren’t effective. Get a .45.” The 9mm of 2021 is light years ahead of the 9mm of the 1990s. Both 9mm and .38 are perfect for pocket carry. As long as a shooter recognizes the limitations of a .380, they are great also.

One of the reasons for the rapid improvement in cartridge quality is the availability of cartridge testing materials available to everyone. A few years back, I was the only one in my region mixing Vyse gelatin in my garage. Now everyone is buying Clear Ballistics blocks. Because of this, there is a lot of raw cartridge performance data out there, and the average person wants to know if they can count on their cartridge of choice.

Cartridge selection is critical. It is incumbent on the shooter to know the exact capabilities of their gun/cartridge combination. For example, one of the .38 cartridges I carry is marginal in barrier tests. However, I know I can shoot it quickly and accurately, even under pressure, and it does very well in bare gelatin. I avoid cartridges that trend toward clogging the hollowpoint in clothing tests.

Lindsey’s personal EDC S&W Model 38, circa 1970s with a Crimson Trace LG-305 grip.

For smaller pockets, Lindsey uses the LG-405, which is the compact grip version.

Notice the patch of skateboard tape for the thumb. The newer S&W M&P Bodyguard

38 is a great improvement on this gun, but the S&W 340 PD weighs only 11.8 oz.

Quality pocket holsters are designed to be smooth on the inside and tacky on the outside. The purpose is to keep the holster seated in the pocket when the gun is drawn. I have found holster products requiring the user to “push off” the holster, either by a thumb ledge or similar feature, are not as reliable and efficient. There are holsters made of Kydex, or a similar rigid material with a hook that grabs the edge of the pocket when the gun is drawn. I tend to avoid these because it adds “moving parts” to the draw stroke.

It is important the pocket holster covers the trigger guard completely, and a little structural rigidity in this area is critical. My EDC holster has specific fits for pocket guns. It is smooth on the inside and it is tacky enough to be used as an ad hoc IWB rig. I want to make it clear, however, I rarely use this type of holster as an IWB.

DeSantis makes the Super Fly, a second generation of the popular Nemesis. The Super Fly is likely named because the rubberized fabric on the outside locks the holster in the pocket like flypaper. This holster also comes with a removable outer flap designed to break up the print in the pants pocket. This holster has strategically reinforced areas, adding to the ability to secure a master grip before drawing.

The first rule of practice is to establish a routine of drawing and dry firing, including reloading. I have some dummy rounds for speedloader practice, and I shoot at my television often. If you apply this habit, please use safe practices to avoid any tragedy.

Practice maintaining a good drawing stance that allows easy access to the pocket and know your clothing.

As a firearms trainer, I don’t really want students to be forced to use their training. However, it is much better to be well trained and not need it, than … well, you know.