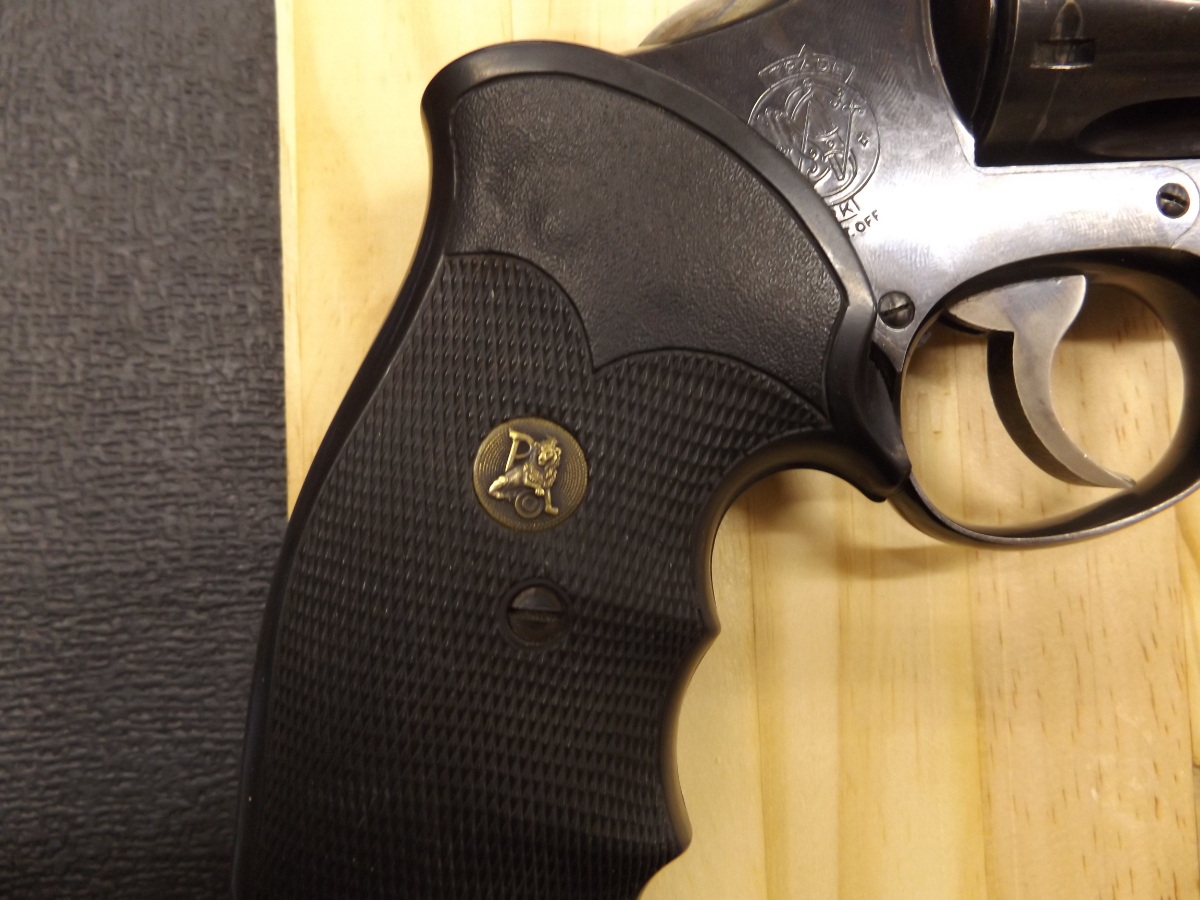

Smith and Wesson’s hand ejector revolvers are easily the most successful revolvers of all time. From .32 caliber I-frame revolvers to big-frame .45s, the people armed with hand ejectors are well-armed individuals.

These revolvers are reliable, often accurate, and handle better than most. When the hand ejector with a swing-out cylinder and simultaneous cartridge ejection was introduced, the trigger-cocking revolver wasn’t new.

But combining a solid frame, swing-out cylinder and reliable lockwork made for a winner. Named the “hand ejector” for the innovative swing-out cylinder and ejector rod, the original was introduced in 1896.

Built on the I-frame, this six-shot revolver was chambered for the .32 Smith and Wesson Long cartridge. The I-frame was a small-frame, double-action revolver. Originally, the bolt stop was located in the top strap.

The bolt stop was later moved to the bottom of the frame window. Considerable modifications resulted in an improved revolver and eventually, the design changed so that the ejector rod locked into a stop at the bottom of the barrel.

The next in Smith and Wesson’s line of hand ejectors was the Military and Police .38. Originally chambered in the military .38 Long Colt, the Military and Police was upgraded to the . 38 Smith and Wesson Special soon after.

The I-frames hung on for many years while the .38 Special hand ejector was to become the most popular police issue handgun of all time.

The .38 Special cartridge became a favorite of those wishing to protect themselves with a fairly light and easy-to-use revolver that offered reasonable power.

Those who must carry a handgun—police, guards and special agents—were armed with the .38 Special revolver for decades.

The .38 Special cartridge had a lot of stretch and further development led to a more powerful combination of velocity, bullet weight and accuracy. The .38 Hand Ejector Military and Police eventually became the Model 10 in 1957.

The K-frame (or Smith and Wesson medium-frame) spawned highly successful handguns such as the K-38 target revolver, the Combat Masterpiece, the K-22 and the .357 Combat Magnum.

The K-frame was the bread and butter of the company and remains in production. Variations include:

During World War II, both Britain and America deployed thousands of Smith and Wesson . 38 caliber revolvers. The majority are five-inch barrel revolvers, but two and four-inch barrel revolvers are encountered. Most were parkerized.

These were known as the Victory Model. They featured a “V” prefix in the serial number, save for very early production.

After World War II, there were important changes. A new short-action lockwork was introduced. This lockwork is more durable and makes for better shooting in both target and combat shooting.

The I-frame was stretched to accept the .38 Special cartridge in a five-shot version and became the Chief’s Special. The new frame is the J-frame.

The Chief’s Special became the stainless steel Model 60 and was later chambered in .357 Magnum, with the .38 Special being the most common chambering. The I-frame was discontinued soon after the introduction of the J-frame.

To replace the . 32 caliber I-frame, the Smith and Wesson J-frame was offered in . 32 Smith and Wesson Long. This is a feeble caliber, accurate and low recoiling, but at the bottom of the list for personal defense.

Just the same, it was a popular cartridge for about 100 years! If you have one of these excellent-but-underpowered revolvers, Buffalo Bore offers much stronger loads suitable for small game and are right on the edge for personal defense.

Hand ejectors excel as personal defense handguns, for field use and for hunting. Even the simplest fixed-sight revolvers are often very accurate. The .32s and .38s are not the whole story. Smith and Wesson introduced the N-frame or large frame hand ejector in 1907.

Originally known as the New Century or .44 hand ejector, the Smith and Wesson N-frame was chambered in .44 Special for the most part with versions in .45 Colt as well.

Eventually, the big-frame Smith and Wesson was manufactured in . 38 Special, .357 Magnum, .41 Magnum, .45 ACP and a few others. These are robust revolvers suited for the most difficult duty. The old long action guns are smooth and useful.

The short lockwork versions introduced after World War II are even faster-handling handguns. Smith and Wesson eventually introduced target grade versions of the N-frame. These adjustable-sight handguns are very accurate and fire powerful cartridges.

The Magnums are among the most accurate and useful of handguns.

My favorite of the big-frame hand ejectors is the Model 1917. Manufactured in great numbers, these revolvers are not as easy to come by as they once were.

I would be more than happy with a modern Smith and Wesson big-frame hand ejector, but the classic 1917 is a useful and reliable handgun. These revolvers are chambered in .45 ACP.

Moon clips allow for quickly loading the cylinder and also make reliable simultaneous ejection possible no matter what the angle of the muzzle. This makes the Smith and Wesson 1917 perhaps the finest combat revolver ever manufactured.

Loaded with the Buffalo Bore hard-cast SWC load in .45 Auto Rim, it is a fine outdoors revolver.

Hand ejectors are still going strong and offer an excellent revolver for personal defense, hunting, home defense, and some forms of competition. They are among the greatest revolvers ever designed.

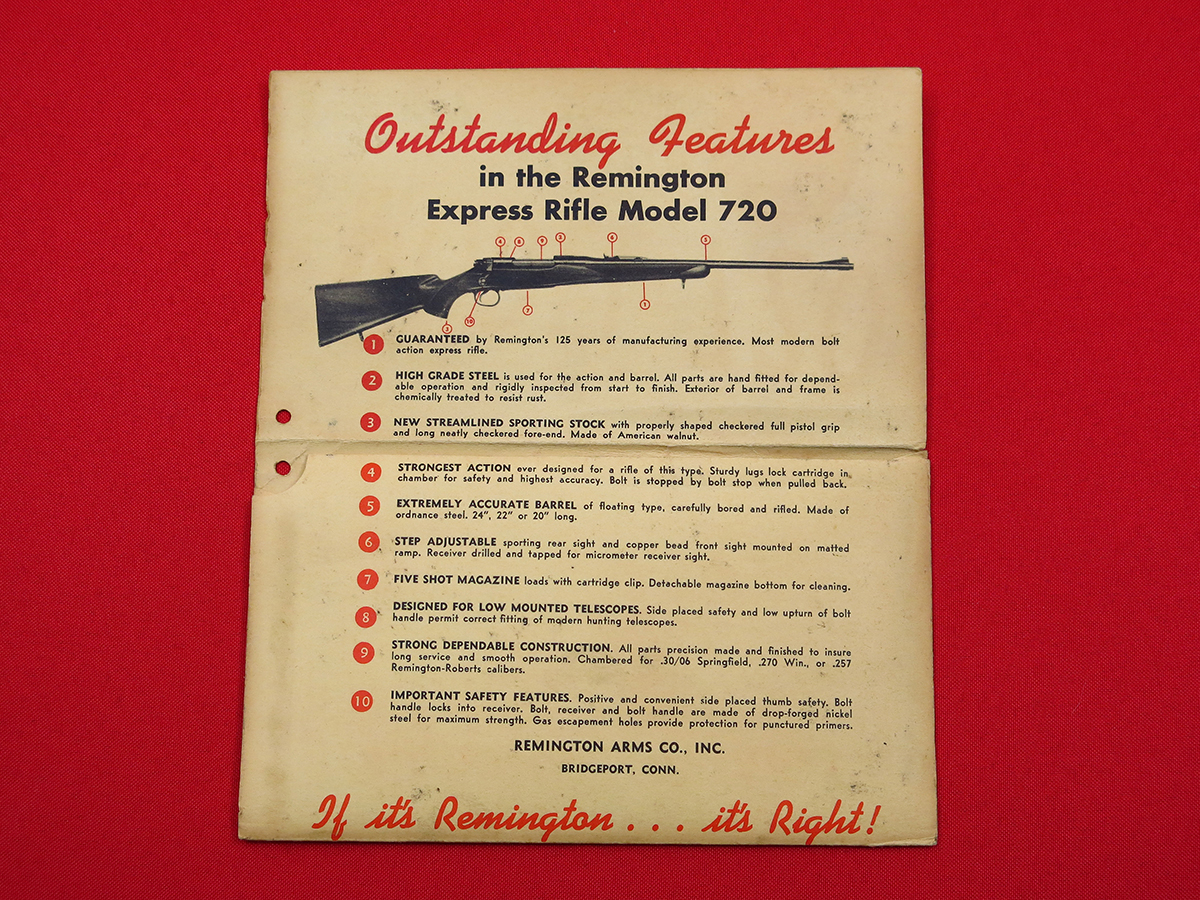

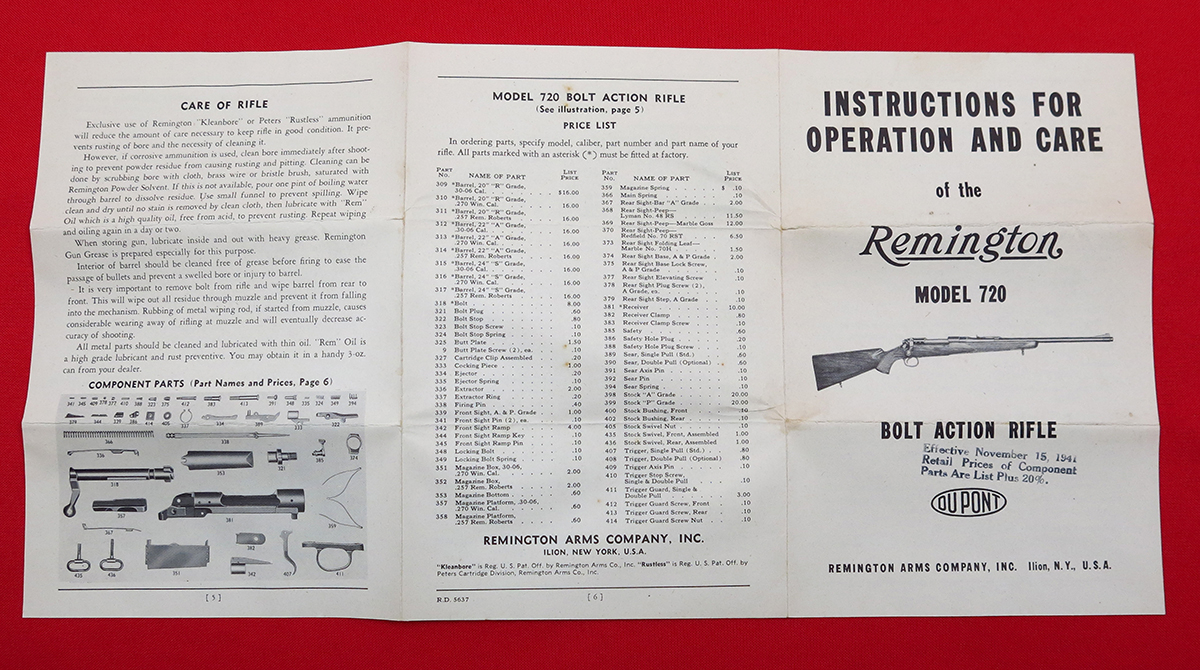

Remington Arms has survived for more than 200 years, through some painful financial times. The company’s foundation is built solidly on tradition and a number of iconic designs, a fact that has allowed it to weather each of those storms. There’s a good reason the brand is a favorite among enthusiasts.

The firm was rolling out some classics in the ’50s and ’60s, including the now-iconic 870 pump-action shotgun that appeared in 1950 and went on to claim the “best selling shotgun of all time” title. The Model 700 rifle arrived in 1962, and there are many others. The list wouldn’t be complete, however, without including the semi-automatic Model 1100 shotgun.

The first Model 1100s came out of the factory in 1963 and were available in several versions, all of them 12 gauge. The Field Grade had a vent rib and plain barrel—$149.95 at the time, if you’re wondering—Magnum Duck guns could chamber 3″ shotshells and a High Grade, with F Premier and D Tournament versions. Models chambering 16- or 20-ga. shotshells hit the market the next year.

The response was a warm one, and sales were good. By 1966, more models were added to the lineup, including one for deer hunting, another for skeet and commemorative versions embellished to celebrate the company’s 150th anniversary.

It became available in 28 gauge and .410 Bore in 1969. The gas-operated semi-auto gained such a sterling reputation for performance, reliability and clean operation that by 1972, the millionth Model 1100 had been sold. That number reached 3 million by 1983, in an era when firearm sales pale by comparison to today’s numbers.

Then, in 1987, the company introduced the Model 11-87. It was an elegant solution for waterfowl hunters facing non-toxic shot requirements. It quickly gained traction among enthusiasts, and the subsequent drop in Model 1100 sales was likely anticipated by Remington.

Despite that fact, both shotguns were a popular choice well into 2000s. In 2016, the company even made a limited-edition Model 1100 to commemorate its 50th anniversary (seen above). Two years later, the corporation that owned Remington Firearms reorganized and, in late 2020, what remained in the gun business was sold in parts during bankruptcy proceedings.

Thankfully, the gunmaking legend is back at it at the Ilion, N.Y., factory, employing many of the same craftsmen, supervisors and management. The company is concentrating initial efforts on manufacturing Model 870s, but plans including bringing back Model 1100s. Variants slated for production include a Sporting 12, Sporting 20 and Sporting 410, each with a high-gloss finish on semi-fancy American walnut furniture (with checkering), blued receivers and barrels, gold-plated triggers and twin bead target sights. MSRPs—along with when we can expect them at sporting goods dealers—are not currently available.