Category: All About Guns

Winchester Shotguns anyone?

15 cm Nebelwerfer 41

Something you really do NOT want in your area shooting at you!

Contrary to what many Americans seem to believe, German hunting rifles have traditionally been lightweight and well-balanced. They often include engraved hunting scenes, but some are relatively unadorned. Perfect examples are the new Mauser Model 12 and Sauer Model 101 bolt-action rifles, which are designed specifically for the American market. Their designs are also related, not surprising since Mauser Jagdwaffen and J.P. Sauer & Sohn are part of the same ownership group, and in fact share the same German address.

Most important, however, is the fact that both rifles shoot very well. Fine accuracy is expected in Germany, since the nation’s culture reveres precision in all things mechanical. Plus, rifled barrels were invented there just about 500 years ago, and Germans really know how to make them. Yes, they cost more than average American-made factory rifles, but a lot less than the typical modern American custom rifle-essentially a rebarreled factory action with an aftermarket synthetic stock. The traditional high level of accuracy of German firearms made me eager to take these two rifles to the range.

My first order of business was mounting a scope on each rifle, a synthetic-stocked Sauer Classic XT in .270 Win. and a walnut-stocked Mauser in .300 Win. Mag. Since mounting new scopes on new rifles can create mysteries unsolvable by Sherlock Holmes, I chose to mount well-proven scopes on each rifle, a 3-9X36 mm Swarovski Z3 on the .270 Win., and a 6X42 mm Meopta MeoPro on the .300 Win. Mag. Attaching the scopes revealed one of the features meant to appeal to an American audience. Many European rifles require bases rarely used in the U.S., but the Sauer 101 uses Remington Model 700-pattern bases, and the Mauser 12 actually uses the ubiquitous mounts for commercial Model 98 Mauser actions. How refreshing! With their respective scopes, rings and bases in place, the Sauer .270 Win. weighed 7 pounds, 12 ounces, and the Mauser .300 Win. Mag. weighed 8 pounds, 1 ounce, both very portable.

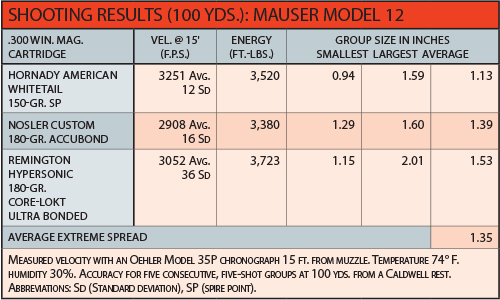

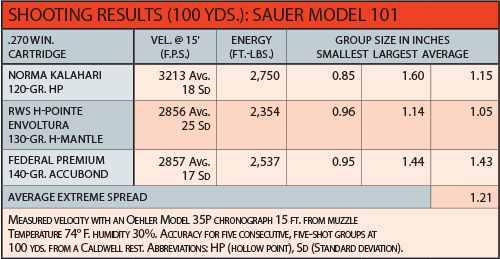

Most American hunters favor three-shot groups these days, apparently because there’s more chance of three shots clustering into the 1/2 inches necessary for slaying 21st century whitetails. But since three-shot groups normally average about two-thirds the size of five-shot groups, the latter indicate far more about a rifle’s accuracy potential, which is why they are part of the American Rifleman testing protocol. Given that, the Sauer’s 1.21-inch group average and the Mauser’s 1.35-inch group average, barely more than 1 inch with RWS ammunition featuring the 130-grain H-Mantel bullet, represents entirely acceptable accuracy. In addition, it would be relatively easy to develop handloads for even tighter groups with either rifle. Finally, consider that, aside from mounting the scopes, both rifles were right out of their shipping cartons. There was no tweaking of the stock bedding, adjustment of the triggers, and the stock screws were all tight. That’s not unusual for German rifles.

The trigger pulls exhibited almost no creep or over-travel, and averaged 1 pound, 14 ounces, on the .270 and 2 pounds on the .300, varying no more than an ounce. The trigger mechanisms appeared to be identical, typical modern “enclosed” designs with a couple of hex-head screws for adjustment, even though none was needed.

A Hawkeye bore-scope revealed each barrel to be as finely finished as hand-lapped American custom barrels. Even with close to 100 rounds fired through each rifle without cleaning, only faint traces of jacket fouling appeared, one reason each kept shooting very accurately throughout the tests. Those fine barrels are press-fit into the actions, and the bolt’s locking lugs fit into recesses in the rear of the barrel itself, instead of the action. The six lugs are machined from the round bolt, and triangularly arranged in two rows.

Some shooters used to two-lug bolt actions with screwed-in barrels will probably whine about the 60-degree bolt lift, or not being able to have their local gunsmith change barrels. But the desire to change the chambering of your rifle every few months, whether because of boredom or the introduction of a new “Wonder Cartridge,” is far from universal, and if you happen to shoot enough to wear out a Sauer or Mauser barrel then you can also probably afford to send the rifle back to Germany for a replacement. (A new barrel probably won’t cost any more than having a typical American gunsmith screw in a new barrel, and probably won’t take any longer, either.) Pressing the barrel into the action also results in a very stiff connection, another reason for the accuracy of both rifles.

Personally, I’ve become more fond of 60-degree bolt lifts through the years. They typically distribute firing stresses more evenly than classic two-lug actions, also promoting accuracy, and make scope-mounting much easier. With the larger scopes on many hunting rifles these days, it’s common for bolt handles on two-lug actions to interfere with mounting exactly the scope we want, at the height we want. With a 60-degree bolt lift this seldom happens. Yeah, a 60-degree lift gives up some leverage, but not enough to make any difference when we use ammunition loaded to normal pressures. The bolts of both rifles are the same length and diameter, and the locking lugs identical. The handles are placed differently, with the Sauer’s exhibiting a distinctly swept-back configuration and a threaded-on polymer knob, but the only substantial difference is the safety system-in both rifles incorporated in the bolt shroud.

In several ways the Mauser rifle is more in the American style than the Sauer. One reason  is the three-position safety, a lever on the right side of the shroud resembling the Model 70 Winchester’s, considered by many American shooters to be one of the best arrangements ever devised for a safety on a bolt-action rifle. The Sauer’s is essentially a tall, triangular “tang”-style sliding safety pad, with a round button on top, that moves rearward and engages with a “click” to hold back the firing pin. The button must be depressed for it to move forward to the firing position, which exposes a red painted bar. Like the Mauser’s safety, when on safe it holds the firing pin back. (I tend to agree with Elmer Keith, who believed the best safety placement for any long gun should be on the tang, right under the shooter’s thumb. A tang safety also doesn’t require the long push of Model 70-type safeties, or have a middle position that can cause rare but real problems.) The bolt release on both rifles consists of a small button. It is on the right side of the Sauer’s receiver, but on the left side of the Mauser’s due to the safety lever.

is the three-position safety, a lever on the right side of the shroud resembling the Model 70 Winchester’s, considered by many American shooters to be one of the best arrangements ever devised for a safety on a bolt-action rifle. The Sauer’s is essentially a tall, triangular “tang”-style sliding safety pad, with a round button on top, that moves rearward and engages with a “click” to hold back the firing pin. The button must be depressed for it to move forward to the firing position, which exposes a red painted bar. Like the Mauser’s safety, when on safe it holds the firing pin back. (I tend to agree with Elmer Keith, who believed the best safety placement for any long gun should be on the tang, right under the shooter’s thumb. A tang safety also doesn’t require the long push of Model 70-type safeties, or have a middle position that can cause rare but real problems.) The bolt release on both rifles consists of a small button. It is on the right side of the Sauer’s receiver, but on the left side of the Mauser’s due to the safety lever.

Extraction and ejection are typical of many modern push-feed rifles, with the bolt face almost fully surrounded in a steel rim except for a spring-loaded, sliding-plate extractor and dual plunger ejectors. During development of the actions, occasional ejection problems arose due to empty cases not flying out at quite the right angle. The solution was a pair of ejectors that flip spent cases well away from the shooter, every time.

Both bolts can also be easily field-stripped. With the Mauser’s safety in the middle position (just like on the Winchester Model 70) push rearward on the spring-loaded plunger on the side of the bolt shroud, then turn the shroud toward the bolt handle. The shroud and firing pin assembly essentially pop out, instead of taking several screw-turns to remove like the Model 70 and 98 Mauser. The Sauer’s bolt can be field-stripped in much the same way, by pressing on a small spring-loaded lever on the side of the shroud.

The Mauser’s recoil lug is pinned to the action, and the recoil abutment in the stock is a steel bar held in place by dual hex-head screws. A pair of steel pins on each side of the recess prevent side-to-side movement. The Sauer uses an arrangement called the Ever-Rest, a small aluminum bedding block with a pair of round recesses for two sturdy steel pins on the bottom of the receiver ring. The front end of the action is held in the bedding block by a bolt hidden by the front end of the floorplate, tightened to 60 in.-lbs., with the front “action screw” merely attaching the front of the floorplate to the stock. (As an experiment, after removing the stock I put the rifle together again, torqueing the Ever-Rest bolt to its proper specification, and the 101 started plunking bullets right into the same place.)

This very firm connection is another reason for the Sauer’s accuracy even with the injection-molded stock. Some American shooters are wary of such stocks because some poorly constructed examples exhibited less-than-ideal rigidity. The 101’s stock showed no such weakness. Even when a firm grip was applied around both the forend and barrel, the stock was rigid enough to prevent the free-floated components from touching. This German injection-molded stock, by the way, doesn’t show the typical mold-line down the center; in fact, at first I thought there wasn’t any mold-line, and thought: “How did they do that?” But examination with a good magnifying glass found very faint traces in the typical places.

Some purists will probably object to the cast aluminum floorplates, with detachable polymer magazines. Such features, however, are cost effective and certainly make sense for European customers-both rifles are sold overseas as well. The firearm laws of European countries vary even more than in North American states and provinces, and detachable magazines make dealing with the variations easier. One of my own German rifles, for instance, came with both two-shot and five-shot detachable magazines in order to comply with differing regulations. The Sauer and Mauser are so similar that the same magazines fit both rifles.

The stocks are shaped in the “classic” American style-well, except for the Schnabel fore-end tip on the Sauer, though I’ve noticed more American rifles with Schnabels these days. They actually appeared on many American rifles well into the 20th century, even on many factory rifles, due to the influence of thousands of German-American gunsmiths. Those who don’t like Schnabels may find the Mauser more to their liking as its stock does not have that feature. The stocks won’t fit everybody, but I’m a rather typical American male with a relatively short neck and square shoulders, and even the light .300 Win. Mag. was comfortable to shoot, partly because both rifles have soft recoil pads.

The walnut stock on the Mauser was classically American. The wood wasn’t extra-fancy, but, thanks to the finish, the grain shows up nicely. The 24-line-per-inch checkering is also quite good, with only a few flat-topped diamonds and no over runs, and appears in four panels on both the fore-end and grip for thorough coverage.

Aside from superb accuracy, both rifles functioned perfectly throughout the tests. Rounds could either be dropped on top of the cartridge follower for single-loading, or pushed into the top of the magazine-not always possible with detachable magazines. Ejection was positive and cases all flew in a similar arc. Re-checking the trigger pull weights after testing resulted in exactly the same results. Both rifles are available with either synthetic or walnut stocks, and good adjustable open sights can be ordered as an option. The sights are high enough to work reasonably well with the rifles’ high-combed stocks, which actually slope downward slightly from heel to comb.

In addition to the usual American chamberings from .22-250 Rem. to .338 Win. Mag., both rifles are also available in four traditional European cartridges: 6.5×55 mm, 7×64 mm, 8×57 mm IS and 9.3×62 mm. If I were going to buy one of the rifles for heavier game, the choice would be the 9.3×62 mm rather than the .338. I’ve been hunting with a 9.3×62 mm for more than a decade, and it has all but replaced my .338 Win. Mag. and .375 H&H Mag. for animals larger than deer-it’s just as effective but felt recoil is noticeably less. Also, my 9.3×62 mm weighs only 8 pounds, scoped.

Some shooters tend to go more traditional as they get older, but many of the non-traditional features of the Sauer 101 really appeal to me, especially the safety. Right now I’m thinking about a walnut-stocked 101 in 7×64 mm, combining traditional German styling with 21st-century German engineering, which, as these rifles prove, is a hard combination to beat.

Manufacturer: Mauser Jagdwaffen GmbH, Ziegelstadel 1, 88316 Isny, Germany

Importer: Mauser USA, 403 East Ramsey, Suite 301,

San Antonio, TX 78216; (210) 377-2527; mauserusa.net

Calibers: .22-250 Rem., .243 Win., 6.5×55 mm, .270 Win., 7×64 mm, 7 mm Rem. Mag., .308 Win., .30-’06 Sprg., .300 Win. Mag.(tested), 8×57 mm IS, .338 Win. Mag., 9.3×62 mm

Action type: bolt-action, center-fire repeating rifle

Receiver: matte-black carbon steel

Barrel: 24 inches, matte-black carbon steel

Rifling: six-groove, 1:10-inch RH twist

Magazine: four-round detachable box

Sights: none; optional open; drilled and tapped for 98 Mauser bases

Trigger: single-stage; 2-pound pull

Stock: oil-type finish walnut (synthetic optional): length of pull, 145⁄16 inches; drop at comb, 1/2 inch; drop at heel, 1/4 inch

Overall length: 443⁄8 inches

Weight: 6 pounds, 14 ounces

Accessories: owner’s manual

Suggested retail price: $1,799 ($1,499 for synthetic stock)

Manufacturer: J.P. Sauer & Sohn, Ziegelstadel 1, 88316 Isny, Germany

Importer: Blaser USA, 403 East Ramsey, Suite 301, San Antonio, TX 78216 (210) 377-2527

Caliber: .22-250 Rem., .243 Win.,6.5×55 mm, .270 Win. (tested), 7×64 mm, 7 mm Rem. Mag., .308 Win., .30-’06 Sprg., .300 Win. Mag., 8×57 mm IS, .338 Win. Mag., 9.3×62 mm

Action type: bolt-action, center-fire repeating rifle

Receiver: matte-black carbon steel

Barrel: 21 inches, matte-black carbon steel

Rifling: six-groove, 1:10-inch RH twist

Magazine: five-round detachable box

Sights: none: optional open; drilled and tapped for Mauser 98 bases

Trigger: single-stage; 1-pound, 14-ounce pull

Stock: black injection-molded synthetic (walnut optional): length of pull, 141⁄8 inch; drop at comb, 1/2 inch; drop at heel 1/4 inch.

Overall length: 415⁄8 inches

Weight: 7 pounds, 12 ounces

Accessories: owner’s manual

Suggested retail price: $1,499 ($1,699 walnut stock)

Amid the controversy over assault rifles—and specifically, the debate over whether or not guns like the semi-automatic weapon Omar Mateen used to commit the recent massacre in Orlando should be considered “assault weapons” or singled out for restrictions—some consideration of the original design and development of assault weapons is useful.

The assault rifle is a class of weapon that emerged in the middle of the last century to meet the needs of combat soldiers on the modern battlefield, where the level of violence had reached such heights that an entirely new way of fighting had emerged, one for which the existing weapons were a poor match. The name “assault rifle” is believed to have been coined by Adolf Hitler. Toward the end of World War II, the story goes, Hitler hailed his army’s new wonder weapon by insisting that it be called not by the technical name given it by its developers, the Machinenpistole (the German name for a submachine gun), but rather something that made for better propaganda copy. A Sturmgewehr, he called the new gun: a “storm” or “assault” weapon.

At the beginning of the 19th century, soldiers in Europe fought battles exposed in full view of the enemy. Often they moved, stood, or charged in lines or in close formations, in coordination with cavalry and artillery, mostly in the open. They could do this and have a reasonable chance of surviving in part because guns were relatively inaccurate, had short ranges, and could only be fired slowly.

In response, weapons developers in Europe and America focused on making guns more accurate up to greater distances. First they found ways to make rifled weapons easier to load from the front. Next they found efficient ways to load guns from the rear—the breech—rather than ramming bullets down the muzzle of the gun. Breach loading guns can be loaded faster, and the technology made it possible to develop a magazine that held multiple bullets at the ready. These types of battle rifles culminated with the guns carried by the vast majority of foot soldiers in the First and Second World Wars, weapons like the American Springfield 1903 and M-1 Garand, or the German Karabiner 98K: long and heavy guns that fired large bullets from large cartridges and had barrels that were 24 inches long. The long barrels and big ammunition meant that these types of guns could shoot accurately at tremendous distances. Both also packed considerable punch: their bullets left the barrel at roughly 2,800 feet per second.

By the late 19th century, these new guns, combined with machine guns, which were introduced in the 1880s, and significantly better artillery generated a storm of steel so lethal that soldiers had to protect themselves behind cover or in trenches. As a result, soldiers all but disappeared from sight on the battlefield. Tactics changed to hugging the terrain and firing a lot of bullets at an area in the attempt to stop the enemy from firing back, so that other soldiers could move to a better position. Or, there were quick and bloody skirmishes at close range. There was little for soldiers to see, and often they could not expose themselves to take an aimed shot.

In this context, big rifles were overpowered and cumbersome. They also didn’t fire fast or long enough. Soldiers wanted a weapon that could fire on automatic other than machine guns, which still fired big-rifle ammunition and demanded something big and heavy to absorb the recoil. One solution that became popular during the First World War was the submachine gun, which is a machine gun that fires pistol ammunition rather than rifle ammunition. This smaller, weaker ammo made it possible to have a smaller, lighter gun, but the tradeoff was that they had poor range and offered little “penetrating power.” Many armies treated big rifles and submachine guns as complementary weapons, and squads carried both into battle.

A better solution was an “intermediate” round that was neither too big nor too little. Generally speaking, the less powerful the ammunition, the lighter and smaller the gun, and the easier to fire it accurately even when firing automatically. Smaller ammunition means one could pack more into a magazine and carry more into combat, too. The ammunition could not, however, be as weak as pistol ammunition. It had to be big enough and powerful enough to be sufficiently accurate and lethal at useful distances.

The ammunition the Germans developed for what would become the first mass-produced assault rifle, the Sturmgewehr (StG) 44, was the same caliber as the standard German rifle ammunition (7.98 mm) but with a case that was considerably shorter: 33 mm versus 57 mm. This meant that while the bullet was the same size, it was propelled by a smaller amount of gunpowder. The gun kicked less and was easier to control, even when set to automatic, and fired at a rate of 600 bullets per minute. The 98K it was intended to replace was not even semi-automatic. The StG 44 was not lighter than the 98k, but it had a barrel that, at 16.5 inches, was about half a foot shorter. It also had a 30-round magazine, compared to the 98K’s five-round magazine. Of course, the StG 44 packed less punch than the 98K and was not as accurate at extreme distances, but the Germans understood that the StG 44 was deadly enough. Fortunately for the Allies, the Germans did not issue many StG 44s until late in 1944, at which point having a better gun wasn’t enough to turn the tide of the war.

Other countries quickly developed similar weapons. The Soviets, impressed with the StG 44, developed their own version of the gun, called the AK-47. The British took a different approach with the EM-2, which had an even smaller cartridge (.280 caliber, or 7 x 33 mm). The U.S. was more conservative, to the point that the nation forced the British to abandon the EM-2 because the U.S. wanted NATO to accept as its standard ammunition a slightly modified version of the venerable 7.62 x 63mm “thirty-ought-six” used in the M-1, a new round that measured 7.62 x 51 mm.

Still, the Army wanted something better than the old M-1 rifle, which opened the door in the 1950s to new ideas. Two organizations within the military conducted research that helped undermine Army orthodoxy: the Operations Research Office (ORO) and the Ballistics Research Laboratory (BRL). ORO studied the Korean War and came to the same conclusion the Germans had during World War I: Soldiers mostly shot at targets much closer than what they were trained to shoot at and what their guns were capable of hitting. Few even saw targets or aimed; instead, they conducted “area fire,” which means they fired as quickly as possible at an area to suppress the enemy. ORO also determined that in combat the best marksmen fired no better than the worst, and firing quickly was more important than firing accurately, within reason. The BRL analyzed ballistics tests and concluded that the lethality of a bullet had more to do with its speed than with its mass. If a small .22 (5.56 mm) caliber bullet went fast enough, it was as deadly as the NATO 7.62 x 51 mm round—and more accurate. Nonetheless, the Army favored a big orthodox rifle, the M-14, which fired the NATO 7.62 round and had a 20-round magazine. It could fire on automatic, but because of the ammunition it was difficult to control on that setting, and most kept it set at semi-automatic to avoid wasting ammunition.

In 1957 the Army’s Infantry Board invited a civilian engineer named Eugene M. Stoner to review its data. Stoner used the information to develop the AR-15, which he brought to Fort Benning in 1958 for trials. His new gun fired a small cartridge (.223 or 5.56 x 45 mm) very fast, at 3,150 feet per second, and it had a shorter barrel than that of the M-14. It could be fired, controllably, on automatic. The Army tested the AR-15 and found it superior to the M-14 at all but extreme distances and also lighter and easier to control, but remained committed to the M-14. In Vietnam, however, M-14-equipped troops facing AK-47-equipped opponents found themselves in need of a gun that could carry more rounds in its magazine and fire on full automatic. By that time, some American soldiers had been equipped with AR-15s—which the Army named the M-16—and they asked for more. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara prodded the Army into replacing the M-14 with the M-16, and by 1968, the M-16 had become its standard infantry weapon.

Recently American military has been transitioning to the M-4, which essentially is an M-16 with a shorter barrel. Some versions fire three-round bursts rather than full automatic. The M-4 is less accurate at long distances, but the 21st-century battlefield is more urban, and soldiers spend more time getting in and out of vehicles, so the military is willing to accept the loss of a little accuracy for greater ease of use in confined spaces. The gun is also easier to use for smaller people, so better for many female soldiers.

Virtually all the world’s armies now use assault rifles, most of which are variants of the AK-47 or the AR-15. They differ in the details—slightly smaller bullets or slightly bigger ones, longer or shorter barrels, and so forth—which reflect different schools of thought regarding the right sweet spot between power and ease, between full-size rifle cartridges and pistol ammunition. There are also different mechanical approaches to things like how the gun uses the gas from a fired round to reload. The basic idea, though, has remained the same since Hitler gave the weapon its name. Other guns are technically more lethal, and of course different guns are better suited for different purposes. Assault rifles were designed for fighting wars.