Where has all the time gone?” is a well-worn cliché, however, no one has ever been able to answer the question. And the older we get, the faster it seems to go. It only seems like a short time, but it happened 40 years ago. It was on the 4th of July, or as my late brother Terry Murbach always insisted, it was to be called Independence Day. We had had our family barbecue, and I was now home resting and relaxing and looking forward to a quiet weekend. It was not to be.

I received a phone call from a young man who said he was a revolversmith living outside of Cody, Wyo. His name was John Linebaugh and I had never heard of him. He was very enthusiastic about his pet project, and he had my attention, although I must admit I had doubts.

His reaction was to suggest he send me a test gun so I could see for myself. This is what he told me, “I’m sure my guns will stay on a car door-sized target to half a mile if you can hold ’em. They are bigger guns, both in caliber and size. We only claim 50% to 90% over a .44 Magnum, 1,500 to 2,000 foot-pounds energy in 71/2″ or longer barrels.”

That seemed to me an exaggerated claim, but I held on. “Practical, this gun uses .45 Long Colt brass, bullets and readily available components. No brass forming, reaming, trimming, etc. No special dies or malarkey. Use readily available bullets, molds, powder, etc. It is a total custom sixgun in barrel lengths from 43/4″ to 10″ or 12″. It is packable in reasonable-length barrels and handy enough for use from defense to hunting.

The guns hold to the heavy single-action tradition and are not specialized like the single-shot TCs. They can handle factory or equivalent loads and be at home under your pillow or in your belt, or be moved up the ladder to full potential with our recommended handloads and be used successfully on the largest game. I’m old school (that means single-action) and use and build common sense sixguns.”

Easy Power

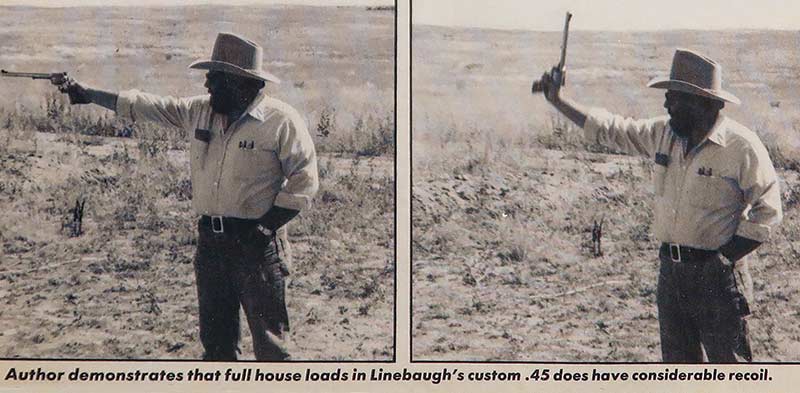

At the time the prevailing wisdom said .45 Colt was weak but after spending two months shooting this first test Linebaugh Custom Sixgun, I was thoroughly convinced everything John said was true. I did take a wooden dowel and mallet with me to the first shooting session. I thought I would have to pound cases out of the cylinder, but it just didn’t happen. All the loads I tried extracted easily. I had no stuck cases, no blown primers, not even flattened primers.

I loaded everything just the way John instructed me including sizing all bullets to .452″ for the .451″ custom barrel. I started with new Winchester-Western brass using CCI Magnum primers. Even with new cases I full-length resized them before loading.

For bullets, I went with the standard Keith bullet, Lyman #454424 as well as 310 and 330 Keith-style bullets. I also sized the Lyman #457124, a 385-grain .45-70 bullet down to .452″. When my first article was published on this Linebaugh Sixgun, the editor decided not to publish the actual loads. The key to making everything work so well was and is tight tolerances and smooth, properly dimensioned cylinders.

Shop Tour

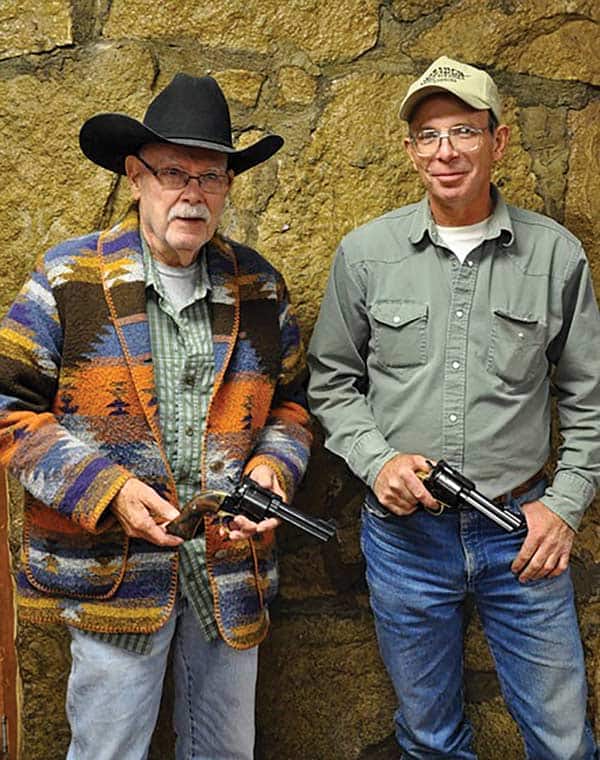

In July 1985, Brian Pearce and I loaded up my Ford Bronco with plenty of ammunition and big bore sixguns along with our sleeping bags and headed over to Cody to visit John. He was living with his wife and two sons, Dustin and Cole, in a small cabin 40 miles outside of Cody. There was no running water, and the family had to carry water from Line Creek in buckets.

Half of the cabin was used for living, and the other half for gunsmithing. A loft provided the sleeping area. We rolled our sleeping bags out on the floor, got up the next morning and had a great time shooting .45 Colt sixguns at long-range. Twenty years later Dustin Linebaugh, a superb sixgunsmith in his own right, his wife, and two young sons visited me and rolled out their sleeping bags in my family room.

John built me two custom .45 Colt sixguns, one being a heavy-duty, 51/2″ Abilene. This gun started as a .44 Magnum, and John re-chambered the cylinder and fitted a new barrel. My friend, the late Charles Able, furnished ebony stocks and over the years, this gun has been used with 260-grain and 300-grain bullets at 1,200 and 1,100 fps. The other one started life as a 2nd Generation .357 Magnum Colt New Frontier. I found a 43/4″ .45 Colt barrel and John re-chambered the original cylinder to a tight .45 Colt.

For many years both S&W and Colt supplied their .45 sixguns with oversized chambers. So much so one could often actually see the bulge in fired brass. This resulted in short case life and mediocre accuracy. With my “new” New Frontier, there was no bulging of brass, fired cases were removed easily from the cylinder, and accuracy was such this .45 New Frontier was a tack driver. I found 20 grains of #4227 under the Keith bullet would shoot one-hole groups at 25 yards. It can still do it, but alas, I cannot.

Big Gun Origins

In the early days, John was struggling driving a cement truck and trying to do gunsmithing and I found out there wasn’t much money for them for Christmas. So Diamond Dot and I went shopping and had a very enjoyable time coming up with gifts for the family. The hardest thing to find was Lincoln Logs. We felt so good about being able to help them and certainly did not look for anything in return. However, it was not to be. John called me and said I should send him a base gun.

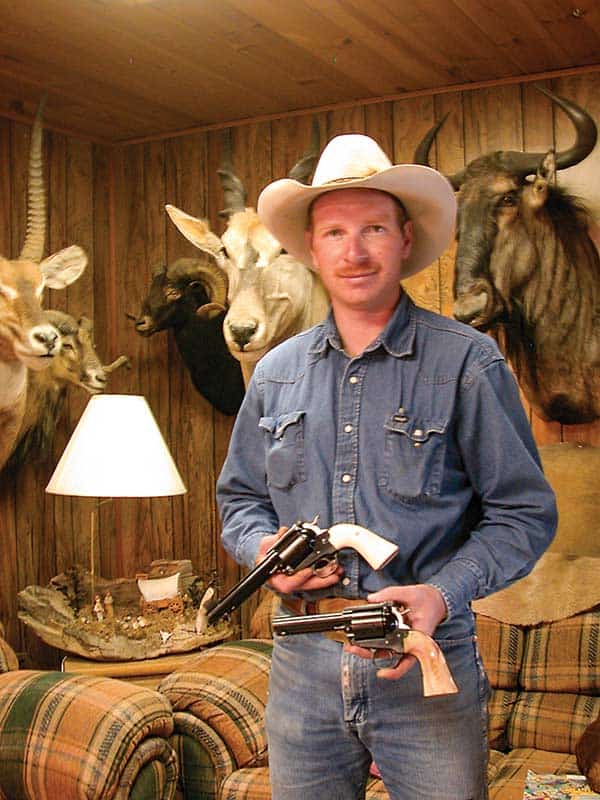

By now, John was building really big guns. He trimmed .348 Winchester brass to 1.410″, reaming the inside of the neck, and the result was the .500 Linebaugh. When my base gun returned, it was chambered in this new, extremely powerful cartridge. Using full loads with 400- and 420-grain bullets resulted in exceptionally heavy recoil. The Ruger Bisley Model, with its grip frame designed for heavy recoil, made the .500 Linebaugh usable.

When it looked like Winchester was going to drop .348 brass, John decided it was best to come up with another cartridge. His favorite rifle was the lever action .45-70. He trimmed this brass to the same length, loaded it with .475″ hard-cast bullets, and the result was the .475 Linebaugh. In the early days, it was necessary to make brass for both of these sixguns. However, it’s much simpler today with properly formed and head-stamped brass for both cartridges available.

The Shootist

In November/December 1984, John published the first issue of the magazine called The Shootist — dedicated to The Old School Sixgunner. John said of this new endeavor: “With this first issue of The Shootist we hope to start the bible of what is nearly a lost art, the art of Old School Handgunning.

We dedicate this first issue fittingly to Elmer Keith, who was indeed a shootist who brought us from the Black Powder era into the smokeless age, polishing and refining his ideas and knowledge with time. What we hope to do with The Shootist is to keep this knowledge alive and circulate it to those who, like ourselves, consider themselves a part of the Old West and Old School style shooter…. Our word is Practical.”

From the first issue in 1984 to the last issue in 1994, John published 15 issues. They were basically photocopies of hand-typed articles just as the writer submitted them; however, the information was and remains priceless. John often said he didn’t like big guns, just big calibers and just as with Elmer Keith, he looked upon the sixgun as something that was easy to pack, practical, powerful and could be carried all day and then placed in a bedroll at night. He opened all new vistas to the art of sixgunning. The above-mentioned sixgun he built for me is a 51/2″ Bisley Model .500 Linebaugh.

Anything In The Lower 48

John became a close friend and I learned to listen to him when it came to anything about sixguns. Over the years, we came to the same conclusion. A large caliber heavy bullet at 1,200 fps is more than adequate for hunting situations and will shoot through just about anything that walks in the lower 48. More muzzle velocity simply flattens out the trajectory, which is rarely of concern for the up-close sixgun hunter.

I settled on 300-320 grains bullets for the .45 Colt heavy duty sixguns using 21.5 grains of W296 or H110 with the 310-grain Keith Bullet, which gives me 1,200 fps from a Ruger 71/2″ .45 Colt Blackhawk. This load is only for heavy-duty sixguns. With the .500 Linebaugh, 29 grains of the same powders under a 440-grain bullet gives the same muzzle velocity from a 51/2″ barrel.

Needless to say, I cannot handle any of these loads at this stage of my life, so with the .45 Colt, 10 grains of W231 gives me 860 fps, while nine grains in the .500 results in 825 fps. They are still powerful loads and manageable for me.

A Legend Lost

For decades John had two carry sixguns: a 4″ S&W .45 Colt for everyday use and a 51/2″ .500 when traveling off the beaten path. In later years, he also discovered the .45 ACP 1911. He always stayed true to his Old School Gunology. John was born in Missouri in November 1955, and like Elmer Keith, he migrated West settling in Wyoming. He was called Home on March 19, 2023. One of his family members wrote the following for his memorial service:

“He smiled his signature smile as he pulled down his old cowboy hat. I asked if this was goodbye; he just shook his head and chuckled. He said that this wasn’t goodbye, just a simple see you later on the other side. I asked him how is this ‘see you later’ when you’re already gone? He said in a cowboy tone, ‘Because one day we will meet again, maybe not here on earth, but one day in another world.’ I have asked him if so, where would we meet?

Then he smiled as he looked up to the sky, ‘It’ll be in greener pastures,’ he said, ‘on the back of two untamed mustangs, that is when I’ll see you again.’ Then I watched as he pulled on his boots and walked out the door. His old-timer’s laugh still filled the room. You could still smell the scent of sagebrush and gunpowder. He laughed as he watched our tears fall. ‘Stop your crying,’ he said. ‘I am up here with the good ol’ boys, catching up on lost time. Stop your tears,’ he said, ‘for I am up here with my Lord and Savior. Stop your tears,’ he said, ‘for I had done my time on this old earth. And boy … It was one hell of a run. Stop your tears,’ he said, ‘for I left the cowboy way … with my boots on.’”

John, keep the beans bubbling and the bacon sizzling, but I have one request. Pick out a mild Mustang for me and I will see you soon.

One mighty nice looking Ruger #1 Grumpy

One mighty nice looking Ruger #1 Grumpy