Category: All About Guns

This is not a 1911. This is not a plastic pistol, a hi-cap anything or even a cutting-edge marvel. There’s no glowing sights, polymer-profoundness or even titanium. Not a lick. Batteries are non-existent here. There are no rails to clip lights to and yes, there’s only five shots. Maybe six, if you really need that last one. It’s old-fashioned, but still good. Dare we say, still great? And that’s why it’s here on our pages.

What you’re looking at is, indeed, the culmination of 150 years of technology, but ancient technology. It’s as if somebody found the hull of an original China Clipper sailing ship, and then lovingly restored it, taking the best ideas from her class of ship. Same ship, same hull, same idea, only she seems to cut the water cleaner, the blocks run quieter, the wheel responds faster and you can swear she knows it. Because, you know it.

So why do we celebrate this old technology when we have much “better” designs today? Just look, and you’ll know why. Put down that Glock and step away from it, then look at these rare few Ichiro photos with a new eye, unencumbered and unsoiled with lightweight thinking or plastic-prodding.

Think on those days when “good” meant “steel,” and “heft” was something men who had carried sixguns in lethal fights would weigh carefully in their hand, as their eyes looked into the distance — or the past? They would then snick the hammer down and hand it back with a nod. “That’ll do,” they might say quietly.

Peacemaker Specialists

Eddie Janis is an artist and a pistol-smith. And a father, husband, admirer of fine cars, good horses, good humor and daughters who behave like ladies. All of which are interconnected, with each one having an effect on all the others. Watch how a man treats a waitress and you’ll have a good idea of the cut of the man. If he’s polite and patient to a young, over-worked waitress, then he’ll probably make a good friend. If he’s rude and short-tem-pered, then take note. By the way, Eddie’s polite to waitresses and has a quick smile— or he wouldn’t be in these pages.

After shooting IPSC into the early 1980s, Eddie lost interest, but discovered the beginnings of cowboy shooting. After having his competition 1911s worked on by talented pistolsmiths, Eddie assumed the same would happen with his SAAs he sent off. But his eyes were rudely opened with the results.

“What I got back was a collection of badly-timed, out-of-balance guns that simply didn’t feel right in my hand,” he said. “My experiences with 1911 ‘smiths and the great work commonly encountered there, made me think there must be a better way when it came to the single action Colts,” he added.

But alas, Eddie was without luck in that department, so, as is the case with such things, Eddie decided he could do better himself. Peacemaker Specialists was born and since those early days, Eddie’s shop has become a Mecca for Colt shooters. From a series of parts care-fully crafted to match factory-original ones (Peacemaker Parts), to a cross-sec-tion of custom work the imagination can only touch upon, Peacemaker Specialists is indeed the “one-stop shop” for all good things when it comes to the Colt Single Action Army. By the way, don’t even mention any of the clones. Eddie doesn’t work on them, period. And that’s, that.

The Question at Hand

The creation on our pages began life in 1902 when it left the Colt factory. It led a mysterious life (if only we knew the adventures), until it was inherited by one of Eddie’s customers (from a great uncle, it seems), and Eddie ended-up with the old Colt in 1999. After languishing in his safe for several years while Eddie “thought on it some,” as he told me, he began a three-part project in May of 2002. He wanted to showcase just what Peacemaker Specialists could do, and offer the final result in steel and ivory.

Eddie calls the first step, “The accuracy phase” and lays it out for us. “A new 7.5″ second generation barrel allowed me to install the front sight authentically, instead of the latter second generation method,” said Eddie. Then, after cutting it to 4.75″ and crowning it, he installed the front sight with the proper solder joint and profiles to match the v-groove rear. Plus, the perfect bore of the new barrel would assure top-notch accuracy.

The second generation caliber mark-ings and address had to be polished off and the correct first generation two-line address and “45 Colt” markings were applied. The forcing cone was cut to 11-degrees for best accuracy with lead bul-lets, and fit to the frame with .002″ to .003″ of barrel to cylinder gap. A standard Colt can be upwards of .006 — or worse.

The cylinder was replaced with a new, second generation .357 Magnum one, re-chambered to .45 Colt with .452″ chamber throats for best accuracy. Eddie applied some hand-magic to the outside of the cylinder to achieve the proper first generation contours and appearance. When all was said and done, he then fit the cylinder with a new base pin and bushing to achieve zero end-shake.

Reliability Phase

Since the innards of the old Colt were tired, Eddie replaced the entire array with new, Peacemaker Parts versions. Since they are virtually identical to original Colt parts (including finish, etc.) they are historically accurate — which is something to keep in mind if you’re restoring an original gun.

Eddie performed his “Gunslinger Deluxe Action Job” on the Royal Flush. This includes, but is certainly not limited to, fitting an oversized bolt and hand, allowing a perfect lock-up with zero side-play in the cylinder; and careful hand-fit-ting of the mainspring, sear and bolt spring, base pin bushing, trigger, ejector spring, latch unit, ejector tube and all screws.

“Hand-fitting” is lots different from “putting in some parts” in a SAA. Beware those “drop-in” spring kits, Eddie warns. “The interplay of parts is critical and simply replacing a spring without making sure the sear engagement is safe and reli-able, may make a gun unsafe,” he explained. The proof is in your hand when you feel a Janis action. Words like “but-tery smooth” come to mind. When I first felt one, I thought someone had taken the main-spring out of the gun. The degree of smoothness is, simply put, astounding.

As Eddie says, “Carefully fitting the parts will pay dividends in long-term reli-ability. If the various bits are working together, rather than clunking and fighting one another, smoothness and reliability are enhanced.” Not to mention the delight of watching your friend’s faces when they cock a Colt Eddie has worked his magic on. “No, really, it’s supposed to be that way,” you’ll have to say. Again and again.

Cosmetics

And we don’t mean eye shadow. This gun had to have ivory, so it does. Note how the “bark” is incorporated into the overall outside contours. It’s often the little things, and this is one of those little, “big” things.

At this point, Eddie test-fired the Royal Flush with Black Hills 250 gr. cowboy loads to center the group on the target. He was also able to maintain the proper front sight contour so it didn’t look “filed-on” when he was finished. So now, the Royal Flush was mechanically perfect but needed something else. How about engraving?

Eddie selected five Cuno Helfrict engraving patterns, circa 1871 to 1921. He was going for a true turn-of-the-century cowboy look, not too busy but not to plain, either. The engraving was impeccably accomplished by master engraver Clinton Finley, of Redding, California. Clinton spread the designs over the sixgun, blending the talents of Cuno with the lines of the Royal Flush. We think Cuno would have doffed his hat to Clinton’s work.

And, no, actually, that finish is not nickel — it’s silver. Silver has a softer finish and feel, like an antique gown, whose green velvet has attained a state of grace, and when touched makes anyone with any feelings at all pause and ask if they could touch it again, please? The silver delights the eye, without over-pow-ering the engraving or reflecting “too much,” as Eddie says.

The fire-blued screws set the Royal Flush off exactly the way the correct red lipstick (not too dark, not too light) can set off a beautiful woman’s lips as she looks— through you. Impossible to believe, but there, before you, nonetheless.

But Why?

Simply to behold, we think. And yet, I was fortunate enough to handle this dream-gun. Don’t tell Eddie, but I cocked it. Honest. Sorry Eddie, I had to. The Royal Flush could hold its own with any of the classic masterpieces of the late 1800s, except for one very important dif-ference.

The Royal Flush shoots like hells-afire, with 100-percent reliability. All of which is no small feat with a single action army. And, I might add, the Royal Flush accomplishes it all in spades. Sorry, I had to say it.

COLT HBAR M2 BELT FED MACHINE GUN

This belt-fed iteration of the M-16 was basically an experimental firearm. Only 20 of these guns were ever made before the project was canceled. Chambered in 5.56x45mm, this machine gun has a 21-3/4″ heavy profile barrel with a bipod attached right behind the three-prong flash hider. Here is how Morphy Auction describes the feeding mechanism of this gun:

Colt then added a very clever belt feed mechanism, that sits in the magazine well when the rifle is opened and locks in when the rifle is closed. The vertical actuator attaches to a special cut in the bolt carrier group to actuate, and a slot was added on the right side, where a feed chute would feed spent links into a separate compartment of the feed box.

Marines and the M1 Garand.

Due to its impressive combat performance during the Second World War, Gen. George S. Patton dubbed the M1 Garand “the greatest battle implement ever devised.” That said, the Garand did suffer some setbacks over the course of its design, trial and ultimate adoption by the U.S. military. One of the most commonly held misconceptions of the entire process is the claim that the United States Marine Corps was entirely uninterested in a semi-automatic service rifle but finally came to adopt and love the M1 Garand and, with that, replace the time-honored M1903 Springfield.

One frequently repeated notion is that the Marines fought the adoption of the Garand because of a belief that it would waste ammunition and degrade their foundational “every Marine is a rifleman” ethos. The story goes: The “Old Guard,” who were more conservative and resisting change, delayed the adoption as long as they could. It wasn’t until after the Guadalcanal campaign in 1942, when Marines fought the Japanese alongside U.S. Army troops carrying the M1 Garand service rifle, that they saw the errors of their ways and left their M1903 bolt-action rifles in the past to adopt the new semi-automatic rifle.

While it’s a plausible theory, especially given the historical conservative nature of military decisions makers, in truth, it is mostly apocryphal and certainly does not tell the story contained in primary source documentation at the National Archives. These documents show a more nuanced relationship between the Marines and the M1 Garand. The chief of ordnance saw the value of an infantryman wielding a semi-automatic rifle against an enemy that would likely field a bolt-action rifle. One of the earliest accounts of this is suggested at Springfield Armory in 1902. However, at that time, they could never get it to work correctly. Even during the First World War, the U.S. Army continually looked for the technological edge on the battlefield in the hands of the rifleman, even investing heavily into the ultimately unnecessary 1903 Mark I and M1918 Pistol (Pedersen Device).

Although that project will go down in U.S. military history as a colossal failure, it didn’t stop the U.S. military. In the early 1920s, two prominent designers were the front-runners in designing the next U.S. infantry rifle on a semi-automatic platform. Those were John D. Pedersen and John C. Garand. Ultimately, John Garand would win the competition, but his story with the Marine Corps is complex.

Initial Interest and Orders

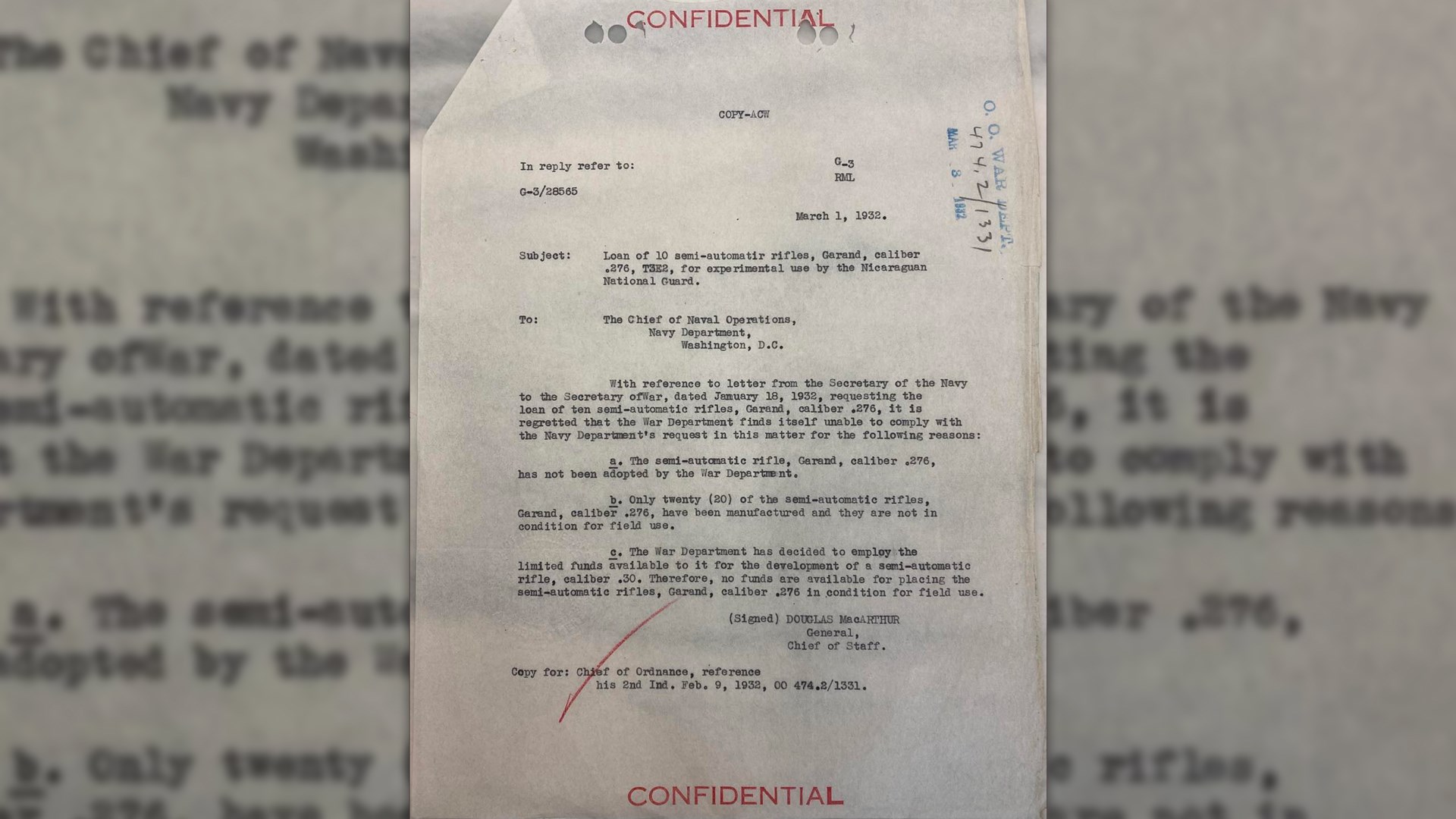

Through the Department of the Navy, the Marines’ interest in the M1 Garand predates the jungles of Guadalcanal by a decade. In 1932, Secretary of the Navy Charles Francis Adams III suggested field trials of John Garand’s experimental semi-automatic rifle (T3E2) chambered in .276 Pedersen. He mentioned that the final test of any tool is its performance in combat. Owing to that fact, he suggested that Nicaraguan National Guard Detachment, which is composed of personnel of the Marine Corps and is frequently engaged in combat in that area, would perform a suitable combat trial. He requested 10 of these rifles with 30,000 rounds of ammunition to conduct a test. General Douglas MacArthur issued a reply in March 1932 that such a test could not be authorized. It should be noted that this predates the adoption of the Garand in .30-06 Sprg., and this suggestion was made while the Garand was still chambered for its original .276 cartridge.

General Douglas MacArthur denies the Marine Corps field test of the Garand semi-automatic rifle (T3E2) in .276-cal. Photo courtesy of Archival Research Group.

General Douglas MacArthur denies the Marine Corps field test of the Garand semi-automatic rifle (T3E2) in .276-cal. Photo courtesy of Archival Research Group.

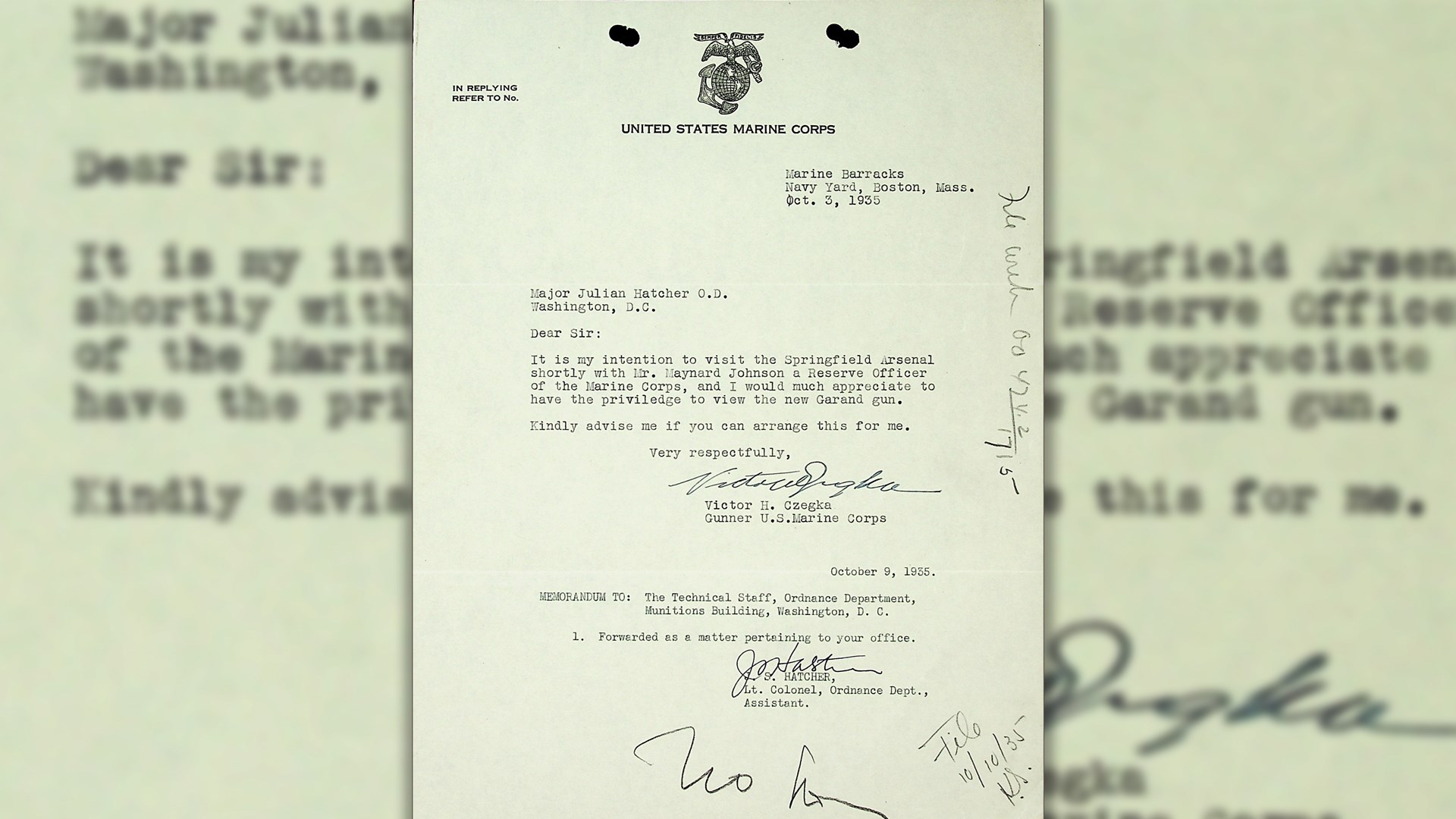

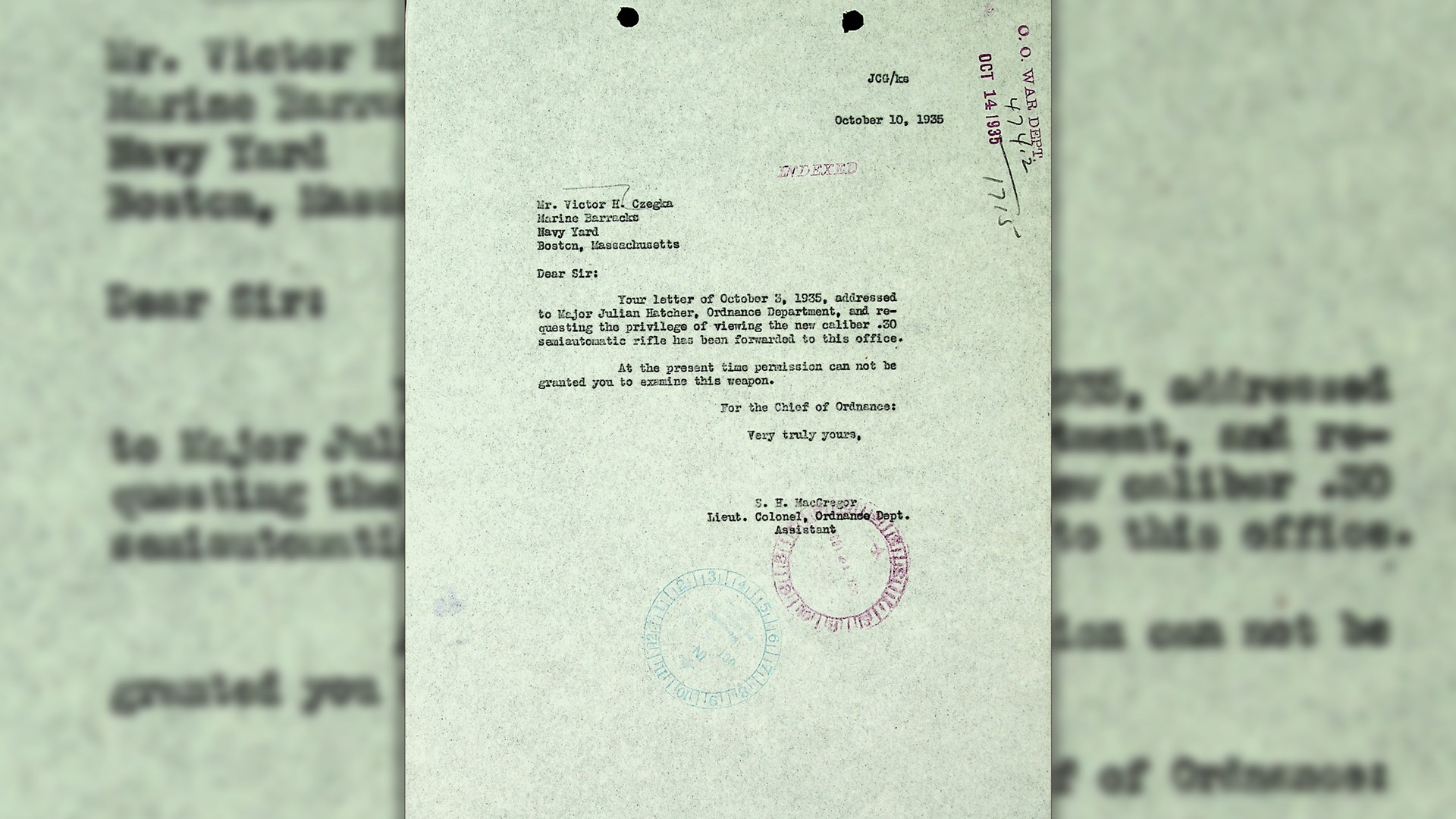

Although the request was denied, the Marines’ interest in the Garand persisted. On Oct. 3, 1935, Victor H. Czegka wrote to Maj. Julian Hatcher of the Ordnance Department that he intended to visit Springfield Armory with Melvin Johnson, a reserve officer of the U.S.M.C. at the time. Specifically, they mentioned they would greatly appreciate the privilege of viewing the new “Garand gun.” It should be pointed out to the readers that Johnson and Czegka were both active in the firearms industry at that time, with Johnson later developing the Johnson Automatic Rifle (itself being eventually evaluated and fielded by the Marine Corps), and Czegka winning the prestigious Wimbledon Cup, a celebrated long-range shooting event. They were well-known personalities, yet on Oct. 10, Lieut. Col. S. H. MacGregor denied their request with a simple “permission can not [sic] be granted to you to examine this weapon.”

The Marine Corps’ persistent interest would continue into early 1936 when the commandant of the Marine Corps placed an order with the chief of ordnance for:

“400 rifles, U.S., semiautomatic, caliber .30, M1, complete with spare parts, equipment common to the caliber .30 M1903 rifle, and except that only four clip-loading machines should be supplied.”

This order amounted to $44,400 plus $100 shipping and handling. This price was later amended by the Paymaster General of the Navy Department to $54,100.00 (with the $100 shipping charge). To add context, this would reflect a price tag of $1,180,714.99 ($2,182.47 shipping and handling) adjusted for inflation to the year 2023.

The first 100 M1 Garand rifles were received at the Philadelphia Depot on March 12, 1938, and retained, awaiting further instructions by the quartermaster of that depot. The following month, on April 8, 1938, Lt. Col. S. P. Spalding wrote the quartermaster of the depot, noting his verbal request that all 400 rifles be provided at approximately the same time. Because of this, and because the Army urgently needed the rifles, it was agreed upon that the U.S.M.C. would return those first 100 rifles to the Army, with 400 rifles earmarked for the Marines after June 30, 1938. On April 22, a memorandum was drafted indicating that the 100 M1 Garand rifles were shipped to the ordnance officer at Fort Benning, Ga., by the Merchant’s Mining Company on April 11th. The Marines’ opportunity to test a semi-automatic rifle would have to wait.

Victor H. Czegka with Melvin Maynard Johnson eagerly requesting permission to see John Garand’s new rifle semi-automatic rifle. Photo courtesy of Archival Research Group.

Victor H. Czegka with Melvin Maynard Johnson eagerly requesting permission to see John Garand’s new rifle semi-automatic rifle. Photo courtesy of Archival Research Group.

The Ordnance Department finally sent some much-awaited news that they would ship 398 rifles to the U.S.M.C. Depot of Supplies on Sept. 15, 1938, and that two rifles had been sent to Marine Corps schools in Quantico, Va., earlier that month. Army Ordnance also wanted to make the U.S.M.C. aware of the long list of difficulties accompanying the rifles and their testing. One of the primary issues was that the standard cleaning rod used was too long. Because the rifle had to be cleaned from the muzzle instead of the breech, it caused damage to the rear wall of the receiver and the head of the bolt, something that was being addressed with the production of a shorter cleaning rod.

Finally, on Nov. 19, 1938, the director of the Division of Operations and Training wrote to the commandant of the U.S.M.C. that a marksmanship and field test should be conducted to determine whether the new rifle, U.S., caliber .30, M1, should replace the M1903 Springfield rifle. He further noted that the current strength of rifle units in an infantry battalion of the Fleet Marine Force (FMF) is approximately 255 enlisted men (armed with the rifle). Owing to the fact the number of rifles ordered (400) provided a sufficient number to equip the rifle units of one battalion, an additional platoon, and furnish several Marine Corps Schools and Basic Schools that, a distribution of the following should be made:

| 6th Marines | 300 |

| 5th Marines | 35 |

| Basic School | 35 |

| Marine Corps Schools | 10 |

| Depot of Supplies (for spares) | 20 |

| Total | 400 |

On Jan. 3, 1939, the commandant of the U.S.M.C. notified the commandant of the Marine Corps Schools at Quantico that they would receive 10 rifles from the Depot of Supplies, which includes two that had already been accepted. He further notified him that the school would be receiving the following:

- Essential parts and accessories.

- Basic Field Manuals for the U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30 M1

- Charts for Instruction

- 1,056 cartridges, ball caliber .30 M1, loaded on clips of (8) cartridges each (1 box containing 132 loaded clips).

The Basic School at Philadelphia would receive the same components above, except getting 35 rifles instead of 10 and 13,728 cartridges instead of 1,056. It was requested that reports be made and returned to the U.S.M.C. Commandant by June 30, 1940, and the reports should contain the following:

- Total ammunition fired.

- Rounds were fired from each rifle.

- Classes of stoppages, causes, and corrective measures for each rifle.

- Malfunctions or broken parts for each rifle.

- Injuries caused by rifles, if any, to personnel.

- A tabulation of firing results for experts, sharpshoots, marksmen, and unqualified personnel.

- Results of musketry and combat firing were tabulated and compared with similar firings done with the M1903 rifle and Browning Automatic Rifle.

- Accuracy of the M1 rifle as compared with M1903 and Browning Automatic Rifle

- Suitability or use in bayonet use.

- Simplicity of mechanical construction.

- Each and Simplicity of assembling and disassembling.

- The suitability of the sights.

- Fatigue from firing the M1 rifle as compared with firing the M1903 and Browning Automatic Rifle.

- Recommendations, if any, for correcting mechanical deficiencies of the rifle.

- Recommendations as to spare parts that should be furnished with each rifle.

- Does the M1 rifle perform satisfactorily in the capacity in which intended, namely as a replacement for the M1903 bolt action rifle?

- Any other information of pertinent nature is not covered above.

Lieutenant-Colonel MacGregor of the Ordnance Department very concisely gave Czegka and Johnson a curt “no” in their request. Photo courtesy of Archival Research Group.

Lieutenant-Colonel MacGregor of the Ordnance Department very concisely gave Czegka and Johnson a curt “no” in their request. Photo courtesy of Archival Research Group.

By February 1939, reports came in from the 6th Marines, 2nd Marine Brigade and Fleet Marine Force in San Diego that many new rifles received had rusted (pitted) barrels when they were received. Reports of any defects were to be reported to the U.S.M.C. commandant at the earliest practicable date. On Feb. 17, 1939, the commanding officer of 1st Btn., 6th Marines, notified the U.S.M.C. commandant of the news. Specifically, he reported that 300 rifles had been received in new arms chests and were packed with heavy oil but not cosmoline. He described the following:

“In general, the rifles were found to be dirty and rusty. Large carbon deposits and powder fowling [sic] were found in the bores and also in the gas cylinders, and rust was noted on some working parts as well. The bores of the rifles were found to be badly pitted to the extent of about 1 in 12 rifles, slightly pitted in about 1 out of 2 rifles, and very slightly pitted in 1 out of about 6. Precisely of the 263 rifles issued and covered by the enclosures, the following conditions were found:

Badly pitted bore…………………….22

Slightly pitted bore……………………152

Very slightly pitted bore………………45.”

Later that month, the Marine Corps Schools at Quantico reported that the 10 rifles it received had no defects upon inspection. The Marine Basic School in Philadelphia noted that its 35 rifles had received prior inspection for defects; each rifle was disassembled and thoroughly cleaned. The barrels and chambers of all rifles were found to be free from defects. However, upon cleaning the grease from the bores, it was noted that the cleaning patches from several rifles came out very black, indicating these rifles had not been cleaned as prescribed and were lucky to escape damage.

The commanding officer of the 6th Marines, 2nd Marine Brigade FMF followed up with a previous report denoting that 13 of the 14 rifles sent to Philadelphia as being pitted and were found mechanically defective from “cuts, flaws and tool marks.” Eight of them were so defective as to be unserviceable. He further noted that a large percentage of the new rifles were not of the type of workmanship that his officers were accustomed to handling.

This parallels a previous report from the commandant, who had noted that Springfield Armory had experienced some issues in the quality of the steel stock purchased for the manufacture of the M1 rifle. The flaws encountered by the Marines in the finished product support this. He further noted that Springfield Armory informed him that it will take some time to adjust the new machines to the type of steel they are using. This accounts for some barrels with tool marks and occasional cuts in the bore. The M1 Garand was going through some significant growing pains before turning into the finished product that served admirably throughout World War II.

The modification (arrow) on the inside of the receiver showing the modification to fix the “7th round stoppage.” The discoloration on the “rib” showing where extra metal was welded to fix that problem

The modification (arrow) on the inside of the receiver showing the modification to fix the “7th round stoppage.” The discoloration on the “rib” showing where extra metal was welded to fix that problem

The situation would get even more complicated when the commanding officer of Co. B, 1st Batn., 6th Marines, 2nd Marine Brigade, stated that the rifles were carefully inspected upon receipt. He noted:

“All rifles were received with bores in a very dirty condition. They have the appearance of having been fired, then greased and packed without previously completing a course of cleaning suitable for prolonged storing. The bores were coated with a medium but sufficiently heavy coat of grease. The mechanical parts were dry, and in some cases, and on a few rifles, rust had begun to appear.” He further noted that, in nearly all cases, the gas cylinders were found to be pitted after cleaning, and the gas cylinder plug was covered with a heavy coat of carbon.

It’s clear that the Marine Corps’ desire to test a semi-automatic rifle was off to a rocky start, and it wasn’t until May 1940 that a full report could be written on how the rifles performed. It should be emphasized that the rifles were first ordered in 1936, and the test wasn’t concluded with a final report until the middle of 1940.

The report indicated that they fired a total of 244,845 rounds in testing during the 1939 targeting year. The report also recorded 131 stoppages, malfunctions or broken parts (this includes disregarding gas cylinder plugs out of line, cracked stocks, etc.). It also reported that 22.1 percent of the present rifles had some stoppage or malfunction that would have put the rifles permanently out of action in the field. Other notable comments were as follows:

- In every instance except one, the M-1 proved superior to the M-1903 in musketry and combat exercises when reduced to the everyday basis of the number of hits scored per round per minute.

- All reports indicated that the M-1 rifle was more accurate than the Browning Automatic Rifle but less accurate than the M-1903.

- M-1 was suitable for bayonet combat.

- The M-1 is easier to assemble and disassemble than the Browning Automatic Rifle.

- There is considerably less fatigue from firing the M-1 rifle than is experienced with the M-1903 or Browning Automatic Rifle.

- The effective rate of fire is 16-20 shots per minute.

- Clips must be handled carefully to prevent rust, denting, or other damage which will cause malfunction.

- It is believed that salvaged clips can be used for a limited time and that most of the ammunition for the M-1 rifle should be purchased already loaded on clips to obtain the best results. Reloading the clips is a slow process.

- The rifle must be fieldstripped for cleaning, which improves the protection of several working parts from loss and dirt during the process.

- The bolt and receiver assembly becomes loose due to wear on the locking lugs.

The M1 debut with the Marine Corps proved rocky but favorable. But the U.S.M.C. understood the M1 was in its infancy and would have improvements made on later models. Some of those recommended improvements included:

- Change the front sight blade to .05 or .06 inch width.

- Reduce the size of the rear sight aperture slightly.

- Improve the design of the rear sight

- Provide a better quality of metal and the fit of the trigger pin.

- Change the design and material in the front hand guards to prevent cracking.

- Modify the method of holding the receiver group in stock to eliminate play which develops due to wear on the locking lugs

- Improve the type of chamber cleaning tool.

And lastly, the most critical question: “Does the M1 rifle perform satisfactorily in the capacity intended, namely a replacement for the M1903 bolt-action rifle?” The report answers this question in this way:

“There is serious doubt as to the suitability of the M1 rifle in its present state of development as a replacement for the M1903 rifle because of: the number of malfunctions experienced, even under satisfactory conditions under which the majority of those tests have been confirmed; the fact that the rifle requires extreme care and lubrication to ensure that it will function properly; and the defects reported by the 1st Marine Brigade FMF, as a result of the limited field test conducted at Culebra. This is especially true when one considers the type of service the Marine Corps as a whole in small wars and landing operations.”

Between the wood is a March 1966 barrel stamp, which was likely due to the Department of Defense overhaul of M1 Garands beginning in 1963.

Between the wood is a March 1966 barrel stamp, which was likely due to the Department of Defense overhaul of M1 Garands beginning in 1963.

The Marines saw value in the new M1 rifle, but it also noted that it was going through some “growing pains.” It also pointed out that the Ordnance Department recently changed the design of the barrel, gas cylinder and gas plug assemblies, and these improvements will go into mass production at Springfield Armory in mid-May 1940. This is when the design evolved from the “gas-trap” Garand to the “gas-port” Garand. These improvements were significant, as they would correct several problems encountered with the earlier designs.

In November 1940, the U.S.M.C. conducted yet another test. This was a competitive test between the M1903 Springfield Rifle, M1 Garand, Johnson Automatic Rifle and a Winchester semi-automatic Rifle. This test concluded that the M1 was superior to the M1903 under favorable conditions and that the M1 was considered suitable for arming components of the Marine Corps, which generally would not be called upon to operate under conditions approaching those of more severe tests. The most interesting comment was, “Judging by the experience with other rifles in the past, and the improvements which have been made and contemplated in the U.S. Rifle Caliber .30 M1, it may be expected that the operation of this rifle will be improved still further.” While the Marine Corps certainly saw the merit in the M1, it just concluded that, in the gun’s present state, it wouldn’t be suitable for front-line combat. The Marine Corps formally adopted the rifle on Feb. 18, 1941, a mere five years after the first purchase order.

Relics From The Tests

One rifle actually used in the early U.S.M.C. trials has been secured for photographs. Its serial number is 3706, and it first appeared on the inspection report from the commanding officer of Co. B,” 1st Btn., 6th Marines, 2nd Marine Brigade, on Feb. 10, 1939. It was noted that, upon inspection, the barrel had pits on lands at a point 5″ from the muzzle, and the gas cylinder was slightly pitted. It appears later in the report from May 1940 where it is recorded it had 260 rounds fired through it during the tests.

Technical Specifications:

Serial Number: 3706

Receiver Drawing Number: D 28291

Barrel Date: 3-66

Stock: Letterkenny Replacement

Trigger Housing: D28290-18-SA

Bolt: D28287-12SA

It’s unclear how long this rifle stayed in Marine Corps custody, because it appears to have returned to the Army at some point in its service life. In April 1941, the Ordnance Department acknowledges an inquiry from the Marine Corps quartermaster concerning the conversion of (gas trap to gas port) 400 rifles on hand at the Philadelphia Navy yard. The Ordnance Department suggests shipping those rifles to Springfield Armory to be converted. It is unclear if these rifles were in fact shipped to Springfield Armory, if they were exchanged for new rifles or if they were converted and shipped back to the quartermaster.

Receiver leg electro-penciling “LEAD” indicating overhaul at Letterkenny Army Depot in September 1966.

Receiver leg electro-penciling “LEAD” indicating overhaul at Letterkenny Army Depot in September 1966.

The toe of the receiver is marked “LEAD 9-66,” which stands for Letterkenny Army Depot with the month and year of its overhaul. Beginning in early 1963, the Department of Defense began a plan of overhauling M1 Garands starting at Springfield Armory. Still, it would carry over into other arsenals around the country. The stock also possesses the “red triangle,” which is the mark of a Letterkenny replacement stock.

Red triangle marked stock which is a Letterkenny replacement stock.

Red triangle marked stock which is a Letterkenny replacement stock.

It has been long believed that the U.S.M.C. fought tooth and nail against adopting the M1 Garand, that the corps wanted to maintain its treasured M1903 Springfield rifle until the Guadalcanal campaign changed their mind. However, looking through primary source documentation, it is clear that this was actually not the case. It’s now known that the Marines took a very early interest in a semi-automatic rifle, dating all the way back to 1932. They would make their first orders in 1936 but would not be able to complete testing and file reports until 1939, due to a series of obstacles. The Marines would then conduct a second test against other possible semi-automatic platforms in late 1940.

The Marines also understood that there was significant value in the M1 Garand specifically. Still, they also understood that, as it stood in its early stages, it needed substantial improvements to reach the level of combat reliability they required. Accordingly, they took a more pragmatic approach to the problem: adopt it as an auxiliary firearm that would be issued to the troops away from the front lines. As the design improvements were adopted, the rifle became more reliable and expanded outwards. Once the supply was sufficient, the front-line combat troops would switch from the M1903 to the M1 Garand. Evidence of this was documented in February 1943 when the U.S.M..C stated it was receiving the M1 in sufficient supply and would transfer excess M1903s to the U.S. Navy. The rest is history.

Picking up where we left off after Special Projects Editor Roy Huntington kindly re-barreled my .32 Colt Police Positive Special, I finally had the chance to handload some of my favorite loads for it. If you remember, the replacement barrel has a thicker front sight on it, so it’s easier for me to see. Because of the thicker front sight, Roy also opened up the fixed rear sight channel for me.

He obviously got things lined up pretty good because the gun shoots to sights with the handloads used.

Name Only?

When certain manufacturers come out with a new cartridge, competing manufacturers don’t like advertising for the competition, so they stamp their own, or some benign moniker for the cartridge. Examples include Ruger marking .45 Colt revolvers with .45 Caliber. Well, Colt was no different. When the .32 S&W Long came out, Colt went with the .32 Colt New Police for the same cartridge.

Handload Heaven

The .32 S&W Long is best suited for quicker burning powders such as Red Dot, Winchester 231, and the old standby, Unique. I use two cast bullets suitable for this gun, both weighing just over 100 grains. The first is an RCBS SWC that looks like a baby “Keith” slug. I’ve always had good luck with this bullet, accuracy-wise, when shooting it in my other .32 H&R sixguns.

The other bullet used is from MP Molds, based in Slovenia. It is a radiused flat-nose design, with a hollow point (HP). It, too, has always shown good manners in the accuracy department and is deadly on varmints with the huge HP cavity.

All loads were assembled using my Lee Precision Classic Turret Press and Lee dies. Since the charges were so small, a Lee Auto-Disk Powder Dispenser was used with the Lee Micro Disk (#441523) since the charges.

I was able to drop 3.0 grains of 231 with this disk. For handloading numerous calibers, the Lee Classic Turret is the way to go. With dies pre-set and stored in the die plate, swapping calibers is quick and easy, taking just seconds to accomplish.

When using 3.0 grains of Winchester 231 powder with both bullets’ velocity runs right at 880 FPS from the 4” barrel of the Police Positive Special. With 3.5 grains of Unique, muzzle velocity was almost identical. Friend Glen Fryxell shared his favorite load of 2.6 grains of Red Dot with the RCBS SWC, and it runs at 800 FPS, also shooting very well.

Shooting

As I mentioned earlier, the replacement barrel has a much thicker front sight (.125”) and is much easier to see with my tri-focal corrective lenses. Being transitional lenses there is no distinct line, rather the focal planes blend into each other. All I have to do is find the “sweet” spot where the front sight looks sharp and clear like it did when my eyes were just 20 years old.

From a distance was 50 feet, I had my hands resting on top of a 12” section of 6” x 6” post standing on end with a sandbag perched on top. The raised position allowed my eyes to automatically align with the “sweet” spot of my transitional tri-focal glasses, providing a sharp sight picture.

My targets consisted of 2” florescent orange squares turned ¼ turn, giving them a diamond shape appearance. Using a 6 o’clock hold with the top of the front sight at the bottom of the diamond shape is natural and provides a wonderful sight picture when everything is all lined up. Groups consisted of five shots each.

Results

First off, shooting these loads is a pure pleasure. There is no recoil to speak off, yet a 100-grain cast slug traveling in excess of 850 FPS packs enough punch to do some damage. Groups were consistently accurate no matter what bullet or powder was used, running anywhere between 1-1.5” as you can see in the target photos.

Shooting old guns with handloads you made yourself is wonderful therapy for beating boredom or taking a break from the routine of shooting modern guns and loads. It’s just different, in its own pleasing way.

Marvelous Misfits

Also of note is shooting a gun once considered a candidate for the scrap heap. With a little computer research, an even better barrel was obtained, making it more suitable for my eyes than the factory original. Plus, I think the heavier barrel looks better.

By making these changes, along with having a friend doing the work, it adds a personal touch to the gun and makes it seem more yours. Old guns taken from the pile of “misfit toys” (referencing “Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer”), and giving them a little care and love, rendering them to shooter status once again, is very satisfying to say the least.

Plus, these “misfits” are usually sold “as is” at bargain prices. So, if you have a little “misfit” in yourself and enjoy making broken guns become shooters again, this is a satisfying and affordable way of keeping yourself occupied until the next project presents itself.

Gov. Jared Polis

While several states have passed laws this legislative session protecting gun owner privacy by prohibiting the use of firearm-specific merchant category codes by payment processors, Colorado has done just the opposite.

On Wednesday, Democrat Gov. Jared Polis signed SB24-066 into law, basically creating backdoor gun registration in the state by requiring use of such codes.

At issue is a new Merchant Category Code (MCC) for gun purchases adopted by the International Organization for Standardization a little over a year ago. MCCs are used by payment processors (like Visa and Mastercard) and other financial services companies to categorize transactions.

This session, legislators in Utah, Kentucky, Iowa, Tennessee, Georgia, Wisconsin and Indiana passed laws prohibiting use of the code. A similar bill is still under consideration by lawmakers in New Hampshire.

State Sen. Tom Sullivan, sponsor of the measure in the Colorado Senate, said the bill is a life-saving measure.

“Credit cards have been repeatedly used to finance mass shootings, and merchant codes would have allowed the credit card companies to recognize his alarming pattern of behavior and refer it to law enforcement,” Sullivan said. “This bill will give us more tools to protect people, and make it easier to stop illegal firearms-related activity like straw purchases before disaster strikes.”

Interestingly, efforts are underway in Congress to outlaw the use of firearm-specific merchant category codes. Republican Reps. Elise Stefanik of New York, Andy Barr of Kentucky and Richard Hudson of North Carolina have filed a bill that would prohibit use of the four-digit code that’s been created to identify merchants selling firearms.

“The tracking of gun purchases is a violation and infringement on the Constitutional rights of law-abiding Americans which is why I am proud to introduce the Protecting Privacy in Purchases Act to prohibit radical gun grabbing politicians from tracking lawful gun purchases,” Rep. Stefanik said in a press release announcing the measure. “I share the concern of law-abiding gun owners across our nation that have voiced their fear that such tactics will work to serve the radical Left’s anti-gun agenda. I will always stand up for our Second Amendment rights as Americans and provide a critical check to any entity attempting to encroach on our liberties.”

The Colorado law will take effect 90 days after the adjournment of this session of the Colorado legislature.

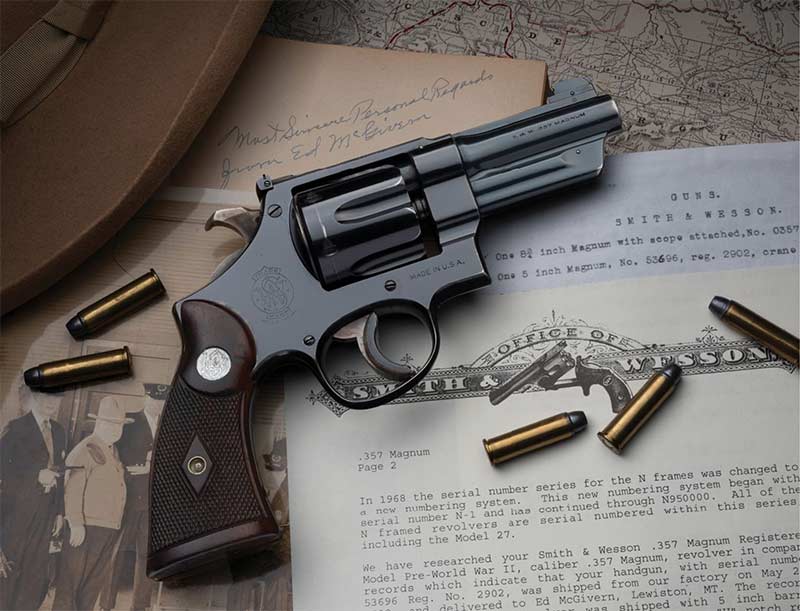

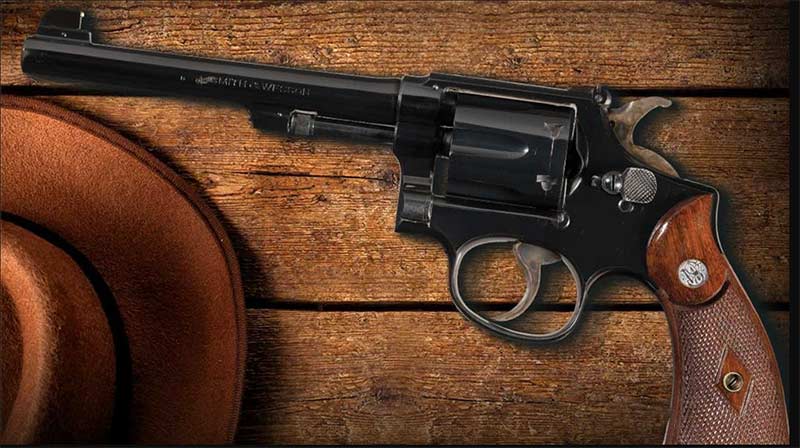

Ask any Smith & Wesson collector, accumulator, or shooter what the most coveted gun displaying the S&W brand is and most likely, they’ll respond “registered magnum” in a confident, obvious-sounding voice.

Introduced in 1935 for the new .357 Magnum cartridge, the gun was essentially a custom-made revolver with hand-fitted parts, along with a “birth certificate” of sorts. Each gun was “registered” and came complete with its own registration card, hence the name “registered magnum.”

Registered magnums are considered the pinnacle of Smith & Wesson production, bringing hefty prices in today’s market. The guns were built to order, with customers specifying the type of finish — blued or nickel, the barrel length ranging from 3 ½” to 8 ¾”, and numerous front and rear sight options. The guns were also sighted-in at 25 yards, with buyers specifying either a 6 o’clock or “dead-center” hold.

In addition to the serial number, each gun was stamped with a registration number, complete with a corresponding registration card. After the purchaser filled out and sent the card back, a certificate signed by Douglas Wesson, confirming the owner’s name, registration number and customized features was sent to the owner.

Famous Registered Magnums

For their upcoming auction on Aug. 25-27, Rock Island Auction Company has a slew of registered magnums previously owned by very interesting people — the most well-known being Ed McGivern from the Dave Ballantyne Collection. Even if these guns are out of your price range, if you bid early, you can always say you had the honor of bidding on one, but it got away. Just reading about these guns and looking at the photos is informative and interesting.

Ed McGivern

Ed McGivern was considered the fastest shot alive before the likes of Jerry Miculek came along. McGivern (1874-1957), known as “the World’s Fastest Gun,” was fascinated by fast shooting after witnessing a shootout in Sheridan, Wyoming. He was a respected and well-known exhibition shooter and hand gunning author of the 20th century who also trained local law enforcement officers and federal agents with the FBI.

McGivern’s book, “Fast and Fancy Revolver Shooting,” was published in 1938. He was known for drawing and firing five shots into a 1-inch group at 20 feet in less than half a second (recorded as 9/20th of a second in August 1932).

The accompanying factory letter states the revolver (Reg. No. 2902) was shipped on May 25, 1938, and delivered to Ed McGivern of Lewistown, Montana, with a 5-inch barrel (currently 3 1/2 inches), McGivern bead front sight, deep “U” notch rear sight (currently a square notch), blue finish, and checkered walnut Magna grips. The letter goes on to state, it was authorized “no charge” by D.B. Wesson and marked “for fast double-action shooting” for Ed McGivern. The auction is Aug. 25, Lot 478.

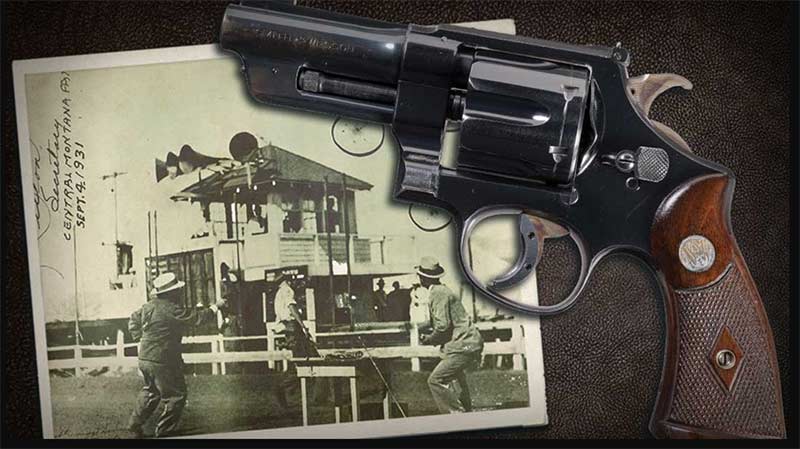

The second McGivern gun available is one of the rarest S&W guns in existence, with only 96 manufactured between 1936 to 1941. A K-32 Hand Ejector Target revolver, these revolvers are in the 653388-682207 serial # range and are square butt “K” target frame five screws, with pinned 6-inch round barrel.

Post-World War II, this model became part of the K-22/K-32/K-38 Masterpiece series of target revolvers. The factory letter confirms the 6-inch barrel, McGivern gold bead front sight, humpback hammer, blued and checkered walnut grips. It was shipped May 10, 1939, to Ed McGivern of Lewistown, Montana.

The McGivern sight, a gold bead on a black post, which is named after him, is the same type of sight on this revolver. The accompanying S&W invoice for this revolver confirms the configuration, as well as Ed McGivern being the recipient. The auction is Aug. 25, Lot 479.

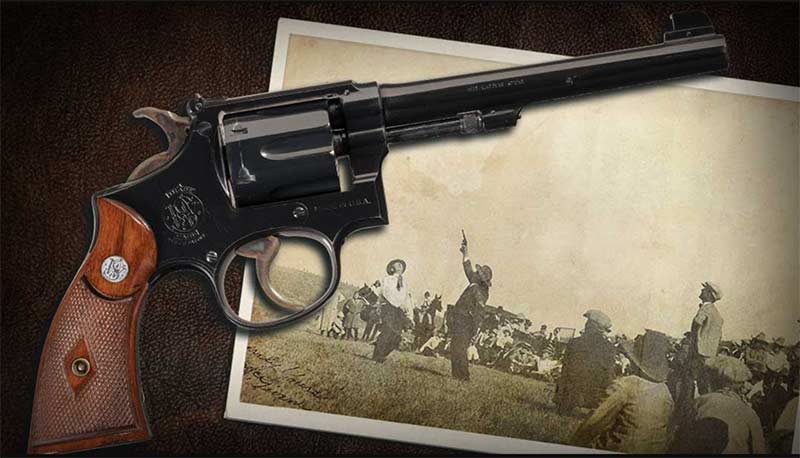

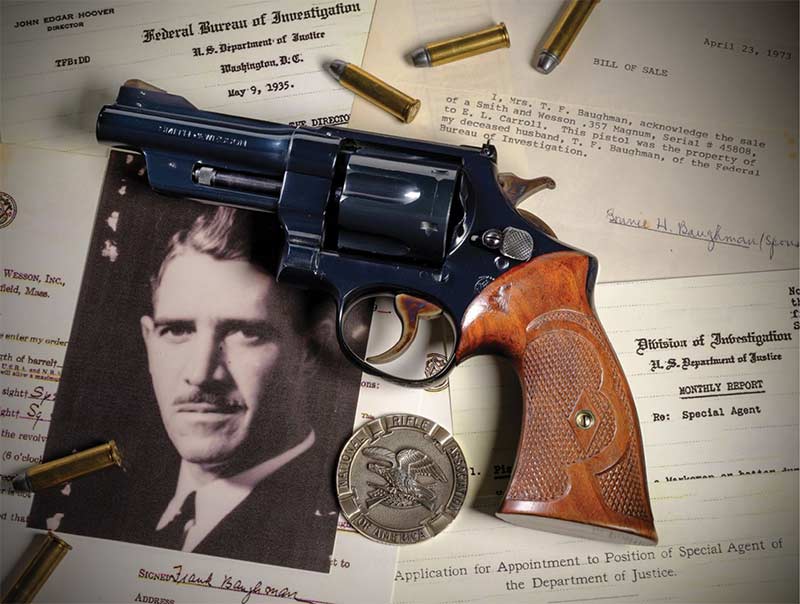

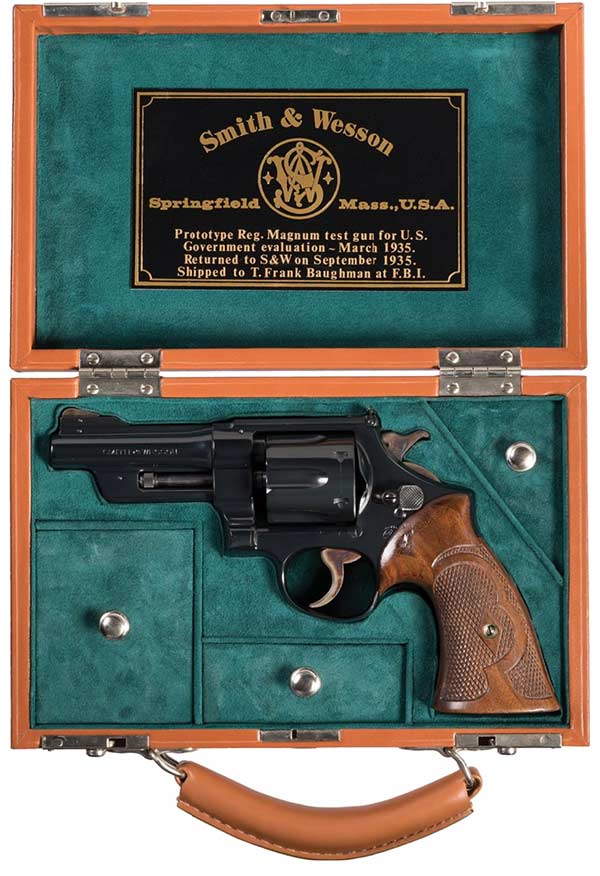

Special Agent T. Frank Baughman

The next Smith & Wesson registered magnum is a historic pre-production S&W .357 Magnum used in U.S. Government Testing & Evaluation by the military and FBI. It was owned by legendary FBI firearms expert and Special Agent T. Frank Baughman, the inventor of the Baughman Quick Draw sight.

As told by S&W historian Roy Jinks in the accompanying factory letter, “This revolver is a very important handgun in the history of the .357 series, being one of the very first .357 Magnums produced for testing and evaluation. Because this handgun was to be used for evaluations, it was not assigned any registration number.

The gun is one of a pair of prototypes assembled in March 1935. Its companion revolver was serial number 45809. The auction is scheduled for Aug. 25, Lot 1498.