Category: All About Guns

Colt Combat Commander

In the English language, the word legacy has multiple meanings. It can be used as a noun or an adjective to describe outdated computer software, a gift by will of an heirloom or money, or something transmitted or received from an ancestor or predecessor.

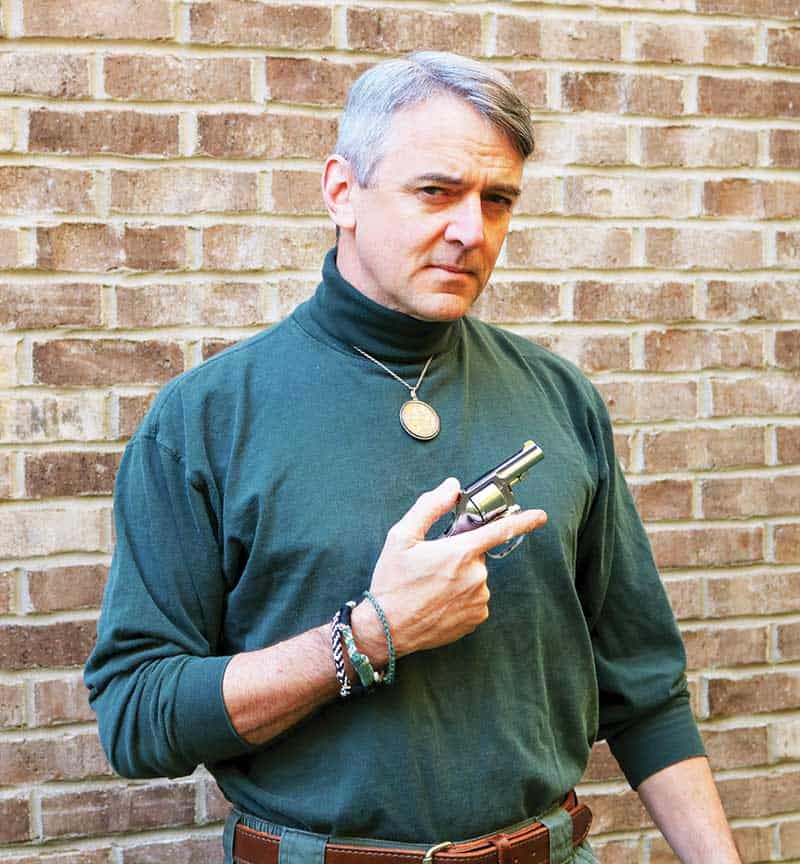

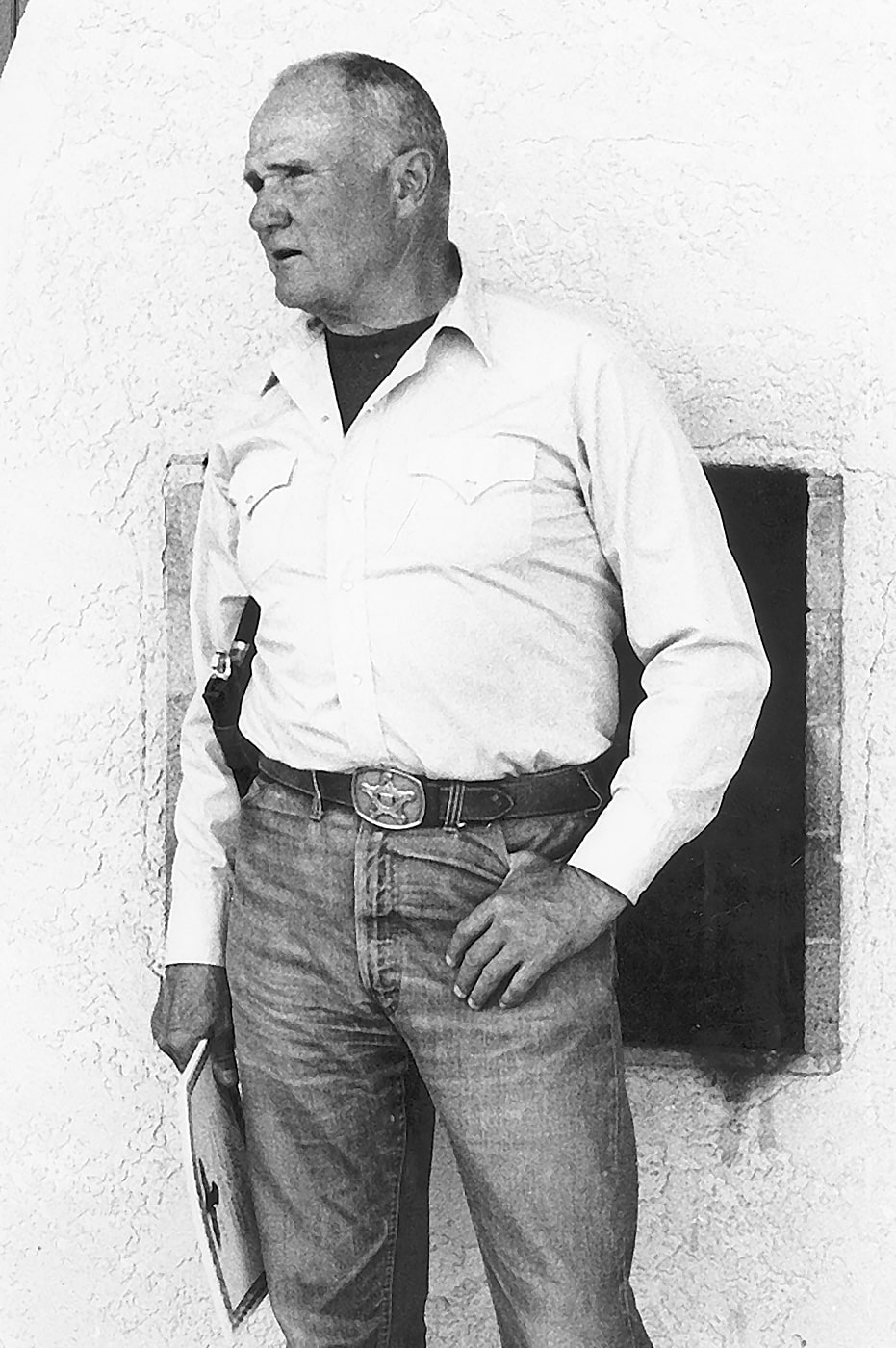

When we consider the origins of modern pistolcraft, the legacy of Jeff Cooper is without peer. The doctrine he pioneered well over a half-century ago rings true to this day and has yet to be surpassed in my opinion. In recent times, a few contemporary trainers have indeed advanced the art, but for me their contributions pale when compared to those of Lt. Col. Cooper.

Throughout his life, Jeff Cooper wore many hats with distinction. He was a Marine officer, shooter, race car driver, big game hunter, instructor and the world’s foremost expert on small arms. He was born in Los Angeles, California in 1920 and was a graduate of Los Angeles High School and Stanford University where he was enrolled in the ROTC.

Just prior to World War II, he was commissioned as an officer in the Marine Corps where he served in the Pacific Theater. After the war, he was transferred to the Marine base in Quantico, Virginia, where he became an instructor in firearms. Because of its close proximity to the FBI Academy, Colonel Cooper was able to interact with members of the Bureau and explore and develop his thoughts on handguns for personal defense.

After leaving the Marine Corps, Lt. Col. Cooper moved to Big Bear Lake in California, where he organized shooting contests called Leatherslap. With his highly analytical mind, he was able to make a determination on what techniques worked best and how they might be applied to personal defense. In many ways, this was the genesis of the Modern Technique of the Pistol.

Around the same time, Lt. Col. Cooper had established himself as a gunwriter of note and soon developed a huge following. In 1976, he established the American Pistol Institute, the first training school to offer combat pistol training to the general population. The school is now known as Gunsite and is widely recognized as one of the world’s most prestigious shooting institutions.

The Modern Technique of the Pistol

Prior to the introduction of the Modern Technique, combat pistolcraft had not evolved much since the 1930s. Large unobstructed targets were the order of the day along with generous time frames. A great deal of unsighted fire was proscribed, often at unrealistic distances. When I first entered law enforcement, this was still the prevailing doctrine and it would be quite some time before things began to change.

The Modern Technique of the Pistol is a total system that addresses mindset and gun handling as well as practical marksmanship. There is much more to winning a fight than being a good shot, and placing equal focus on mindset and gun handling was a revolutionary thought back in the day. Giving equal attention to practical marksmanship, gun handling and mindset describes the Combat Triad, part of his training and the ultimate key to success in armed conflict in my mind.

In many ways, the Modern Technique of the Pistol represented a 180-degree flip over what came before, and much of it was in conflict with what I had been previously taught. I absorbed pieces of it through Cooper’s articles, but at that time I wasn’t able to buy into it fully. However, change was in the wind.

Without question, the FBI holds great influence with other domestic law enforcement agencies relative to both training and equipment. In the early 1980s, the FBI adopted a great deal of the philosophy of the Modern Technique of the Pistol and began to teach many of the components to its agents.

I still have a VHS tape produced by the Bureau at that time and used it for years in my training. With the FBI endorsement of many of its elements, the Modern Technique quickly became very popular in law enforcement circles. As a pretty green firearms instructor at that time, I knew where I had to go to get the real message and shortly thereafter I was able to travel to Arizona and take a class at API.

For those not familiar with it, the Modern Technique is comprised of five elements. They include:

- The Weaver stance

- The flash sight picture

- The compressed surprise break

- The presentation

- The heavy-duty pistol

Even the most casual observer of combat pistolcraft associates Lt. Col. Cooper with the 1911 .45 ACP pistol, and the reason is quite simple. The single-action 1911 pistol is an easy pistol to shoot to a high standard and, back in the day, the .45 ACP cartridge was far superior to the lesser options. Today, with improvements in handgun ammunition, that point may be debated. But at one time, the .45 ACP was the undisputed king of the hill.

SIG MPX PCC Range 2

CLERKE FIRST REVOLVER

THE SKUNKOPOTAMUS OF COMBAT HANDGUNS

In the 1970s the hair was long, the gas was rationed, the interest rates were astronomical and the prevalent fashions could foment blindness if unduly gazed upon. In addition to all this pervasive grooviness, the ’70s also saw the glorious genesis of the absolute worst defensive firearm in all of human history. This steaming pile of ballistic doodoo was curiously titled the Clerke First.

In The Beginning

The 1968 Gun Control Act (GCA) arose in response to the assassination of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Prior to the ’68 GCA, Americans just ordered their firearms through the mail. Afterwards guns had to pass through a federally licensed firearms dealer. The ’68 GCA also codified restrictions on which cheap guns could be legally imported.

These rules were intended to exclude the infamous Saturday Night Specials. This nebulous pedestrian term refers to any inexpensive small handgun that readily lends itself to nefarious applications. To meet the importability threshold, a gun had to have a barrel at least 3″ long and be a minimum of 4.5″ in overall length. There was also a point system based upon such stuff as caliber, weight, construction and sights along with an associated aggregate overall cutoff for importability.

The ’68 GCA excluded a great many handguns previously legal to import. The Walther PPK, for example, didn’t make the cut. The subsequent PPK/S sported a larger frame and an extra round in the magazine and did meet the criteria. This was likely the only example extant wherein a gun got better because of a gun control law.

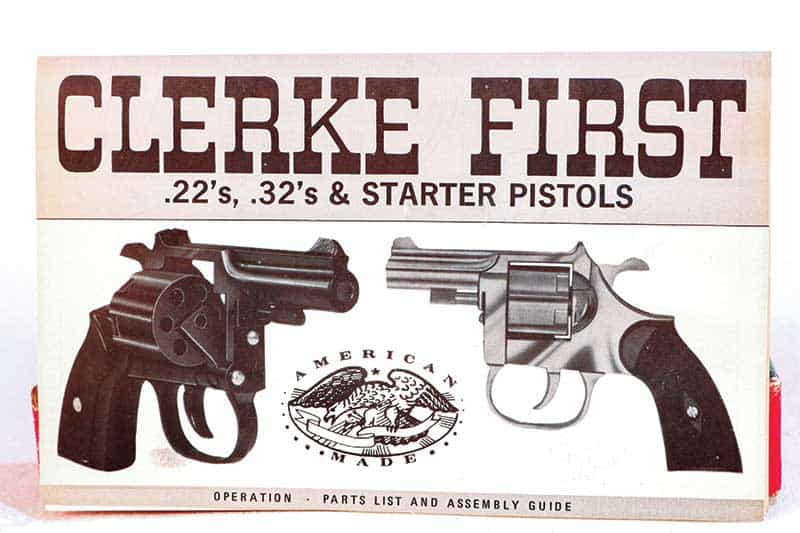

With a substantial slice of the market now left unaddressed, the indomitable engine of capitalism went to work filling it. The end result was the American-made Clerke First revolver. To call this repugnant pistol “crap” would be offensive to feces.

Gross Anatomy

The Clerke First pistol was the brainchild of Clerke Technicorp, an evolutionary extension of Eig Cutlery. Clerke Technicorp is admittedly a pretty cool name. However, when the brain trust finished with the company title apparently their creative well was pretty much spent. The gun’s action began life as a starter pistol and really degenerated from there.

The frame is cast from some sordid sort of pot metal. The trigger and hammer will look familiar to anybody who played with cap guns as a kid. The cylinder is held in place with a rivet. The entire gun is finished in a blinding silver chrome and the grips are black plastic. There was an all-black version as well.

The sights are small, fixed and worthless. The action operates in both single- and double-action modes but is just stupid heavy. There is no ejector.

Manual Of Arms

To run the gun you remove the ejector pin from the front. It is held in place by a spring-loaded detent. A friend who ran a gun shop back in the day said folks were losing these pins all the time. My buddy said he got nearly the purchase price of the gun for a replacement pin. He refused to stock the pistols.

Once the pin is removed, the cylinder will swing out to the right. To remove the empties you push the cases out from the front one at a time using the pin. Drop in five fresh rounds, pivot the cylinder back in place and replace the aforementioned pin. Now you are — technically at least — packing heat.

Will The Poop Collector

I bought my Clerke First revolver new-in-the-box off gunbroker.com for $99. The gent from whom I purchased the gun said he bought three of them on a whim several decades back for $20 apiece. Dealer cost in the early ’70s was $15.

The side of the box sports three check boxes for .32 S&W, .22 LR and Starter Pistol. The frame and works were common to all three. My gun has not been and never will be fired yet it still rattles like Nancy Pelosi’s brain when you shake it. I sought the gun out simply because it was so irredeemably wretched.

Cogitations

You get a sort of gestalt as initially you paw over the Clerke First revolver. The pistol looks and feels like it belongs in a toy box. I’ve read after a few dozen rounds the gun gets as loose as a congressman’s morals.

The Japanese Type 26 revolver is extremely well made but horribly designed. The cylinder spins freely, so you never can be sure if the chamber under the hammer is actually going to shoot or not. By contrast, the Clerke First is just homogenously ghastly throughout. In a pinch, were I to choose between the Clerke First revolver and a baseball bat, I’d be mightily tempted by the bat.

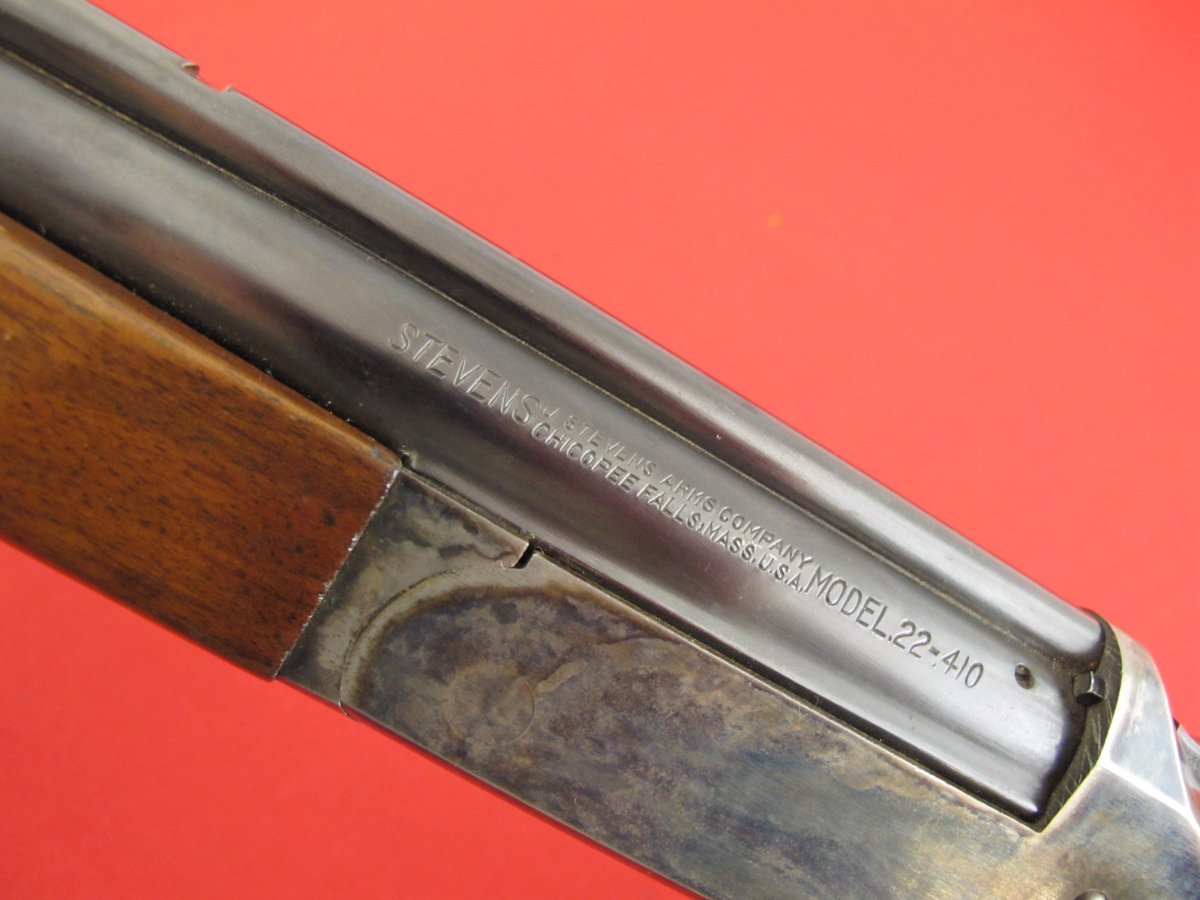

Winchester Model 1895